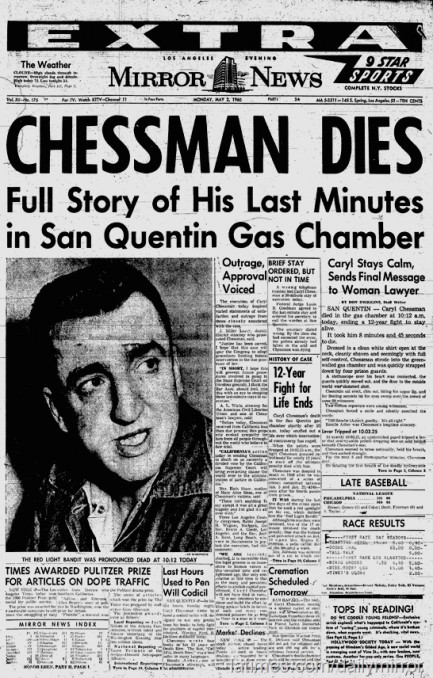

| The Naked City | May 2 2017 |

Did the legal system use him as a pawn, or was it the other way around?

Caryl Chessman and a detective named E.M. Goossen appear in the above photo made shortly after Chessman's arrest in January of 1948. Chessman had robbed several victims in the Los Angeles area, two of whom were women that he sexually assaulted. He forced one woman to perform oral sex on him, and did the same to the other in addition to anally raping her. Chessman was convicted under California's Little Lindbergh Law, named after Charles Lindbergh's infamously kidnapped and murdered son. The law specifically covered intrastate acts of abduction in which victims were physically harmed, two conditions that made the crime a potentially capital offense.

The law was intended to prevent deliberate acts of kidnapping and ransom, as had occurred in the Lindbergh case, but Chessman's prosecutors—demonstrating typical prosecutorial zeal—argued that Chessman had abducted one victim by dragging her approximately twenty-two feet, and had abducted the other woman when he placed her in his car, then drove in pursuit of the victim's boyfriend, who had fled the scene in his own vehicle. Chessman was indeed sentenced to death. The Little Lindbergh Law was revised while he was in prison so that it no longer applied to his crimes, but his execution was not stayed.

During his nearly twelve years on death row he authored four bestselling books—Trial by Ordeal, The Face of Justice, The Kid Was a Killer, and Cell 2455: Death Row, the latter of which was made into a 1955 movie. The books, many interviews, and a steady stream of articles fueled public debate about his looming execution. Among those who appealed for clemency were Aldous Huxley, the Rev. Billy Graham, Ray Bradbury, and Robert Frost. Their interest was not wholly about Chessman so much as it was about the issue of the cruelty of the death penalty, which had already been abandoned in other advanced nations.

In the end the campaigning was ineffective, and Chessman was finally gassed in San Quentin Prison. But even dying, he further catalyzed the death penalty debate. The question of whether a capital punishment is cruel and unusual hinges on whether it causes pain. Gas was held by its proponents to be painless. Chessman had been asked by reporters who would be observing his execution to nod his head if he was in pain. As he was gassed, he nodded his head vigorously and kept at it for several minutes. It took him nine minutes to die. That happened today in 1960.