| Vintage Pulp | May 31 2018 |

It's not perfect, but it's pretty close.

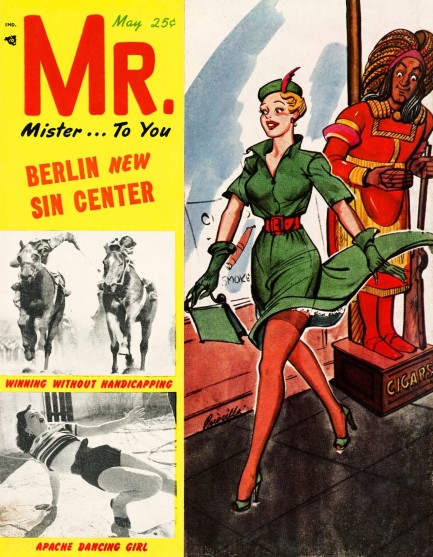

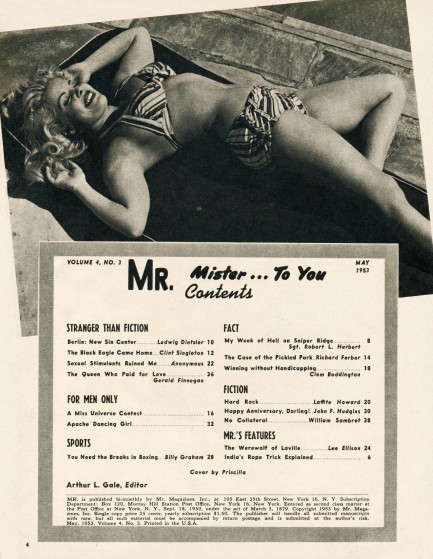

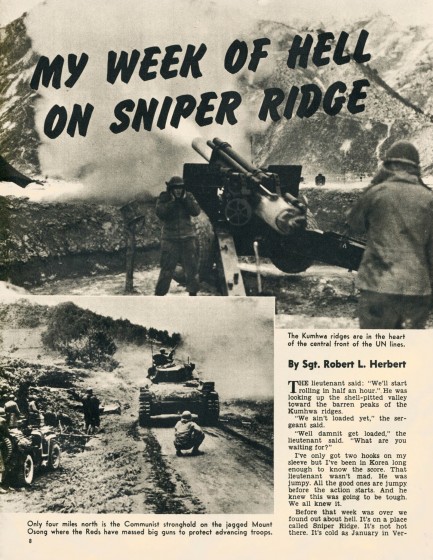

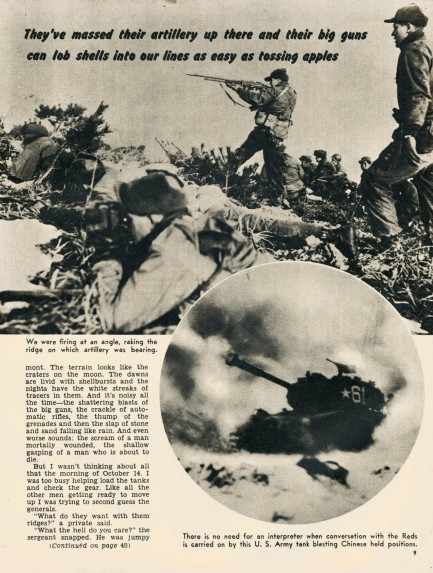

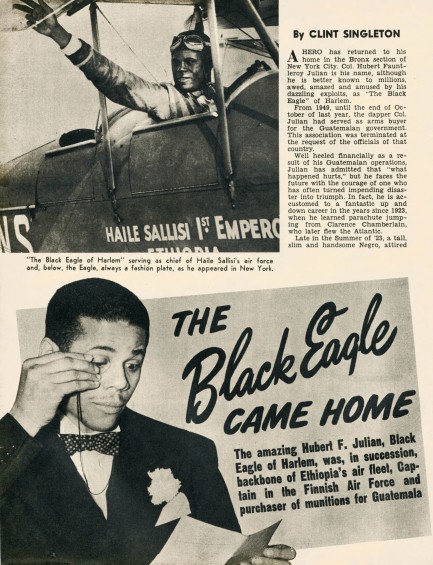

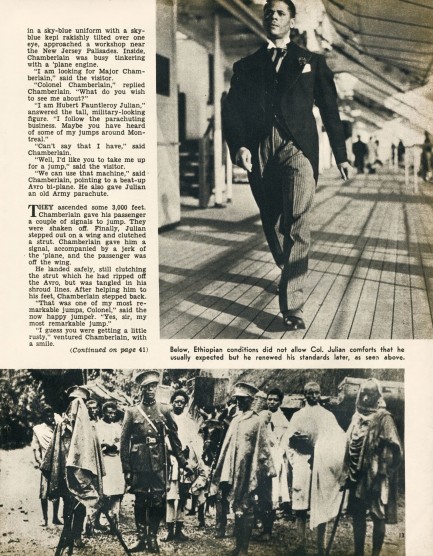

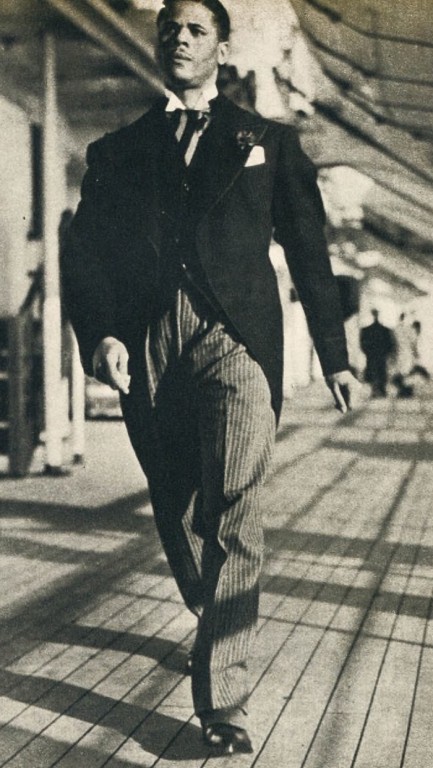

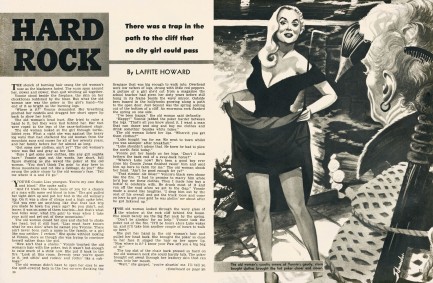

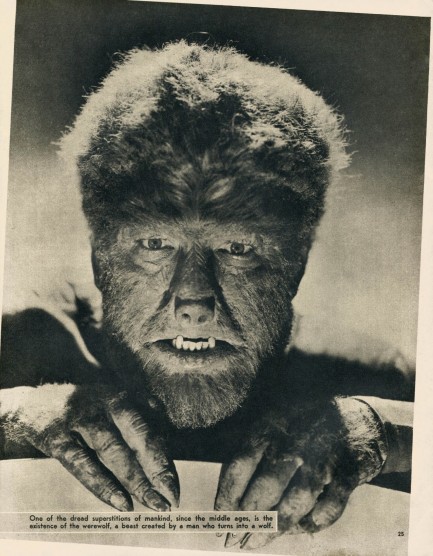

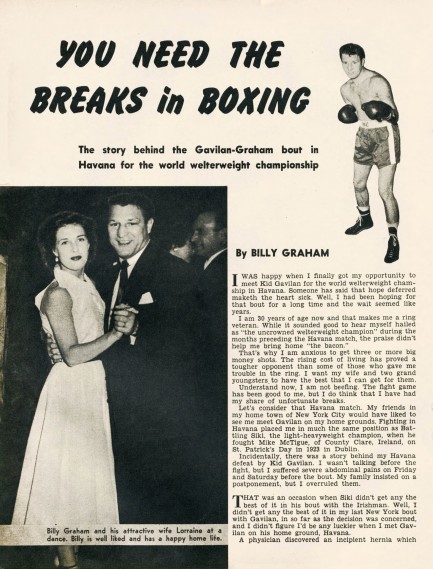

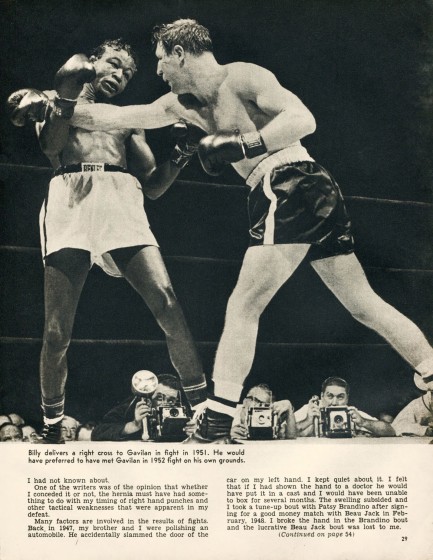

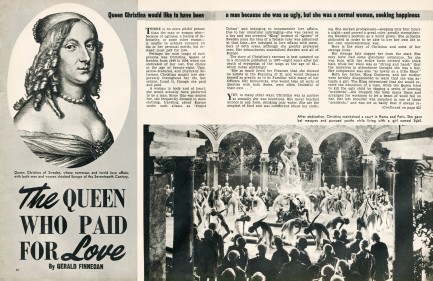

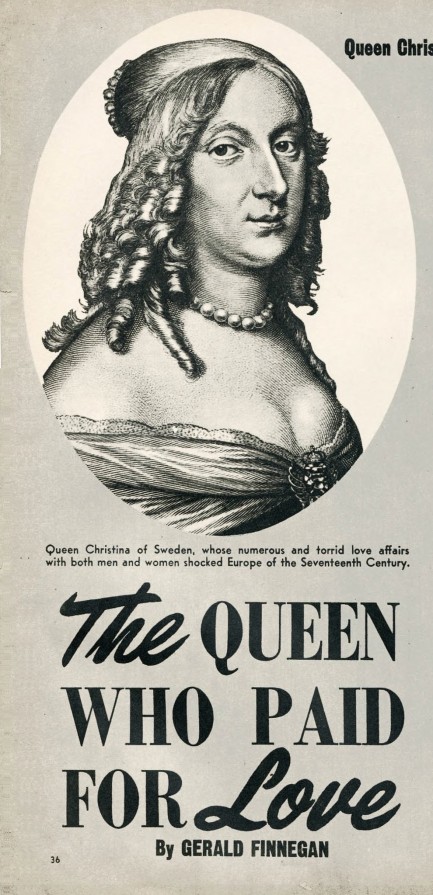

The colorful magazine Mr. was published out of New York City by the imaginatively named Mr. Magazine, Inc., and was in the mold of male oriented publications such as Man's Life or Adventure for Men. This issue is from May 1953 and we grabbed it from the now idle Darwin's Scans website. Queen Cristina of Sweden pops up inside, which surprised us, considering we just learned about her for the first time in our lives less than a month ago and here she is again. You also get contemporary figures such as Billy Graham (the boxer), Kid Gavilan, and Hubert F. Julian, aka the Black Eagle of Harlem.

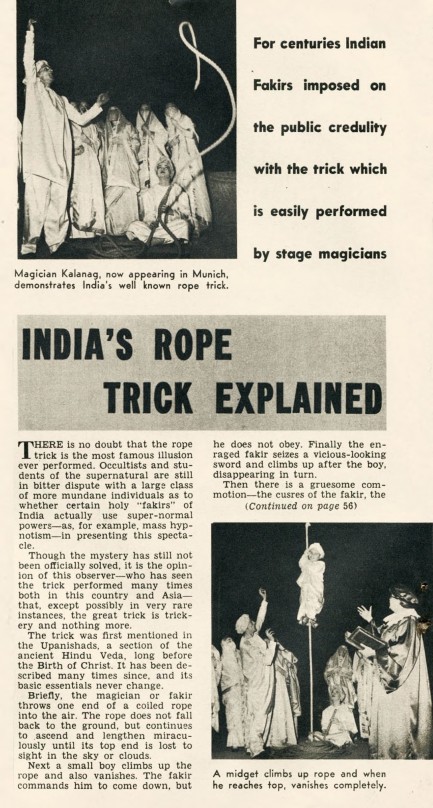

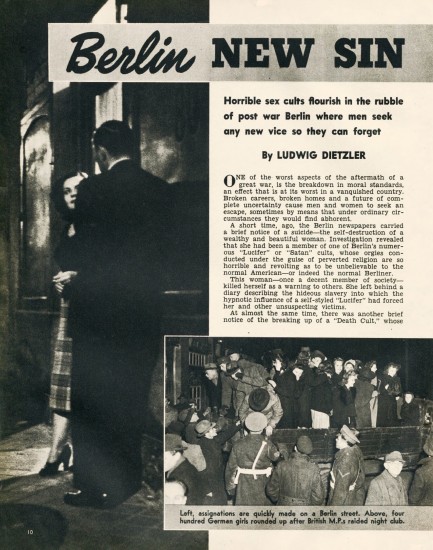

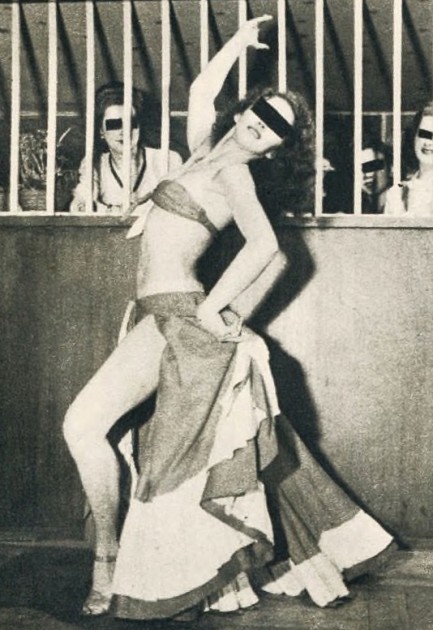

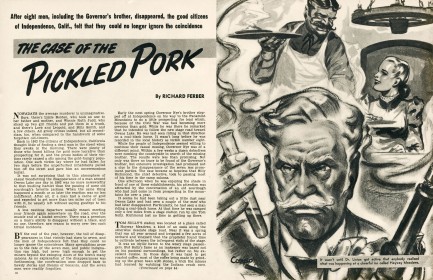

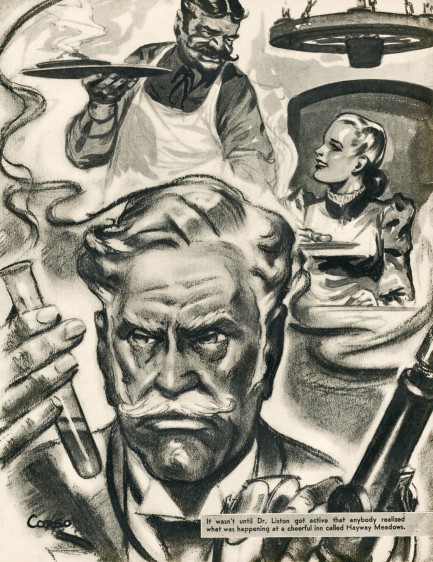

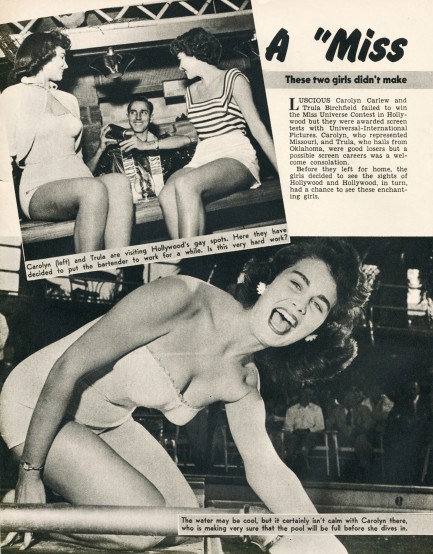

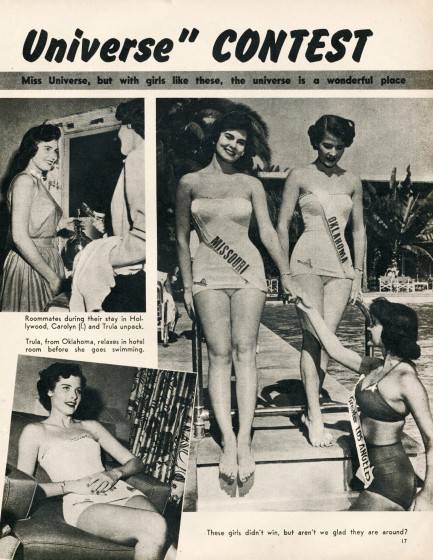

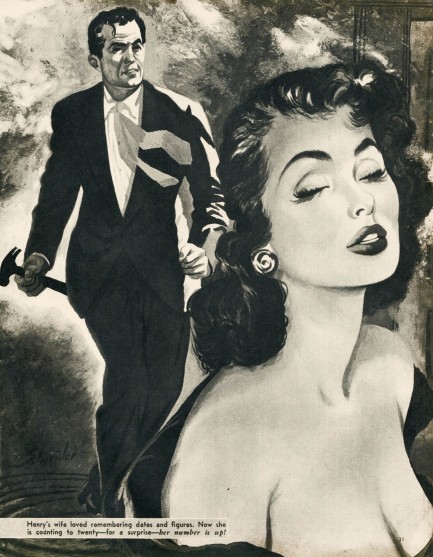

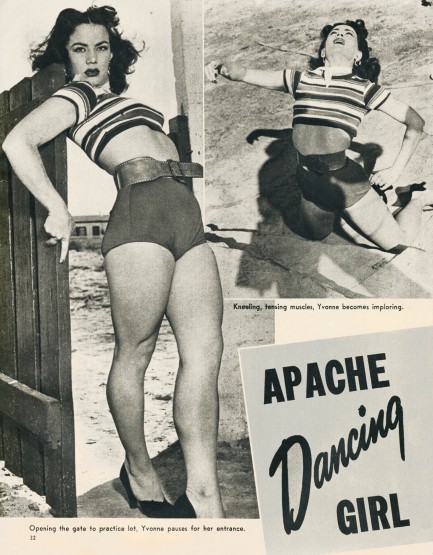

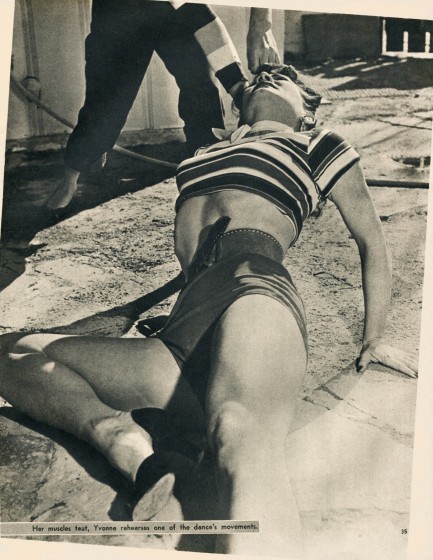

But the magazine focuses mainly on fiction and true adventure. We like the story about Berlin as a center for vice, with “horrible sex cults flourishing” in the post-war rubble. Ludwig Dietzler writes, “I am one of the few non-Berliners who have witnessed the orgies [snip] which thrive in basements, cellars, and other suitable hiding places.” Hmm... it doesn't sound all that bad to us. Elsewhere in Mr. you get beauty queens Carlyn Carlew and Trula Birchfield, as well as Apache dancer Yvonne Doughty. What's an Apache dancer? You'll just have to look. Scans of that and everything else appear below.

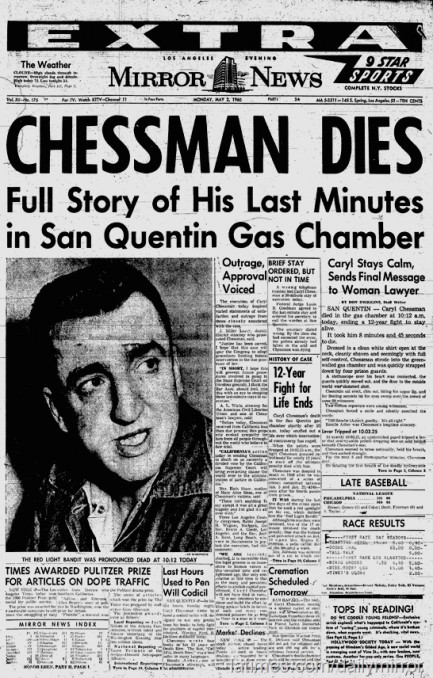

| The Naked City | May 2 2017 |

Did the legal system use him as a pawn, or was it the other way around?

Caryl Chessman and a detective named E.M. Goossen appear in the above photo made shortly after Chessman's arrest in January of 1948. Chessman had robbed several victims in the Los Angeles area, two of whom were women that he sexually assaulted. He forced one woman to perform oral sex on him, and did the same to the other in addition to anally raping her. Chessman was convicted under California's Little Lindbergh Law, named after Charles Lindbergh's infamously kidnapped and murdered son. The law specifically covered intrastate acts of abduction in which victims were physically harmed, two conditions that made the crime a potentially capital offense.

The law was intended to prevent deliberate acts of kidnapping and ransom, as had occurred in the Lindbergh case, but Chessman's prosecutors—demonstrating typical prosecutorial zeal—argued that Chessman had abducted one victim by dragging her approximately twenty-two feet, and had abducted the other woman when he placed her in his car, then drove in pursuit of the victim's boyfriend, who had fled the scene in his own vehicle. Chessman was indeed sentenced to death. The Little Lindbergh Law was revised while he was in prison so that it no longer applied to his crimes, but his execution was not stayed.

During his nearly twelve years on death row he authored four bestselling books—Trial by Ordeal, The Face of Justice, The Kid Was a Killer, and Cell 2455: Death Row, the latter of which was made into a 1955 movie. The books, many interviews, and a steady stream of articles fueled public debate about his looming execution. Among those who appealed for clemency were Aldous Huxley, the Rev. Billy Graham, Ray Bradbury, and Robert Frost. Their interest was not wholly about Chessman so much as it was about the issue of the cruelty of the death penalty, which had already been abandoned in other advanced nations.

In the end the campaigning was ineffective, and Chessman was finally gassed in San Quentin Prison. But even dying, he further catalyzed the death penalty debate. The question of whether a capital punishment is cruel and unusual hinges on whether it causes pain. Gas was held by its proponents to be painless. Chessman had been asked by reporters who would be observing his execution to nod his head if he was in pain. As he was gassed, he nodded his head vigorously and kept at it for several minutes. It took him nine minutes to die. That happened today in 1960.