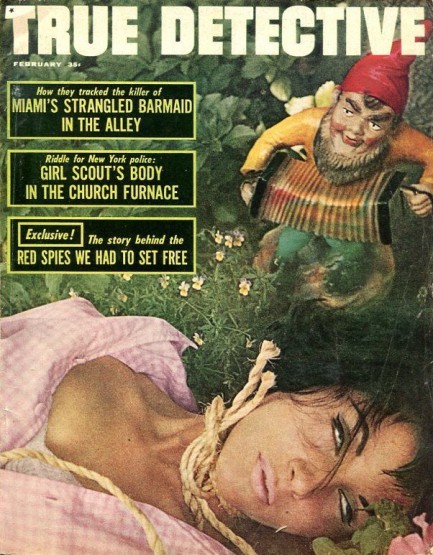

| Vintage Pulp | Jan 12 2016 |

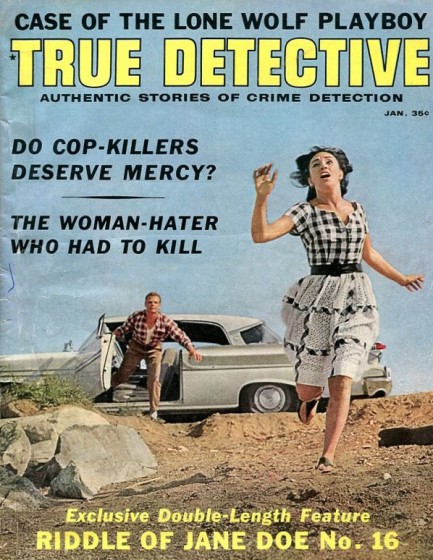

From its founding in 1924 as True Detective Mysteries, through its second iteration and renaming in 1939, True Detective featured painted covers by top artists in the pulp/post-pulp field. The magazine experimented with photographed covers in 1962, releasing two issues of that style. The next year saw photographed covers become the norm and, sadly, another great forum for fine art disappeared forever. That said, some of the new photocovers were good, such as this one from January 1964 showing a kidnap victim fleeing her captor. As you can see, it sought to replicate the style of the painters by using careful staging, and in this case was particularly successful. But soon enough the covers turned into this—i.e., little more than snapshots.

| The Naked City | Jun 11 2015 |

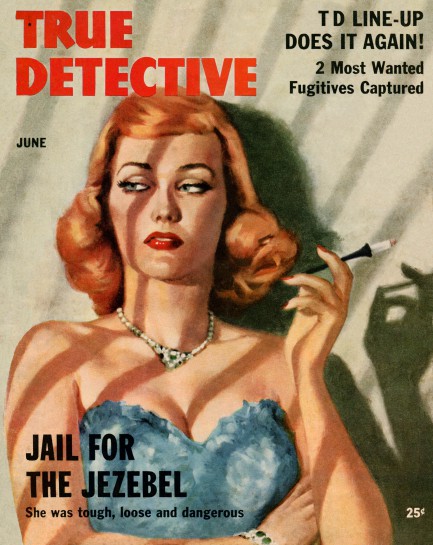

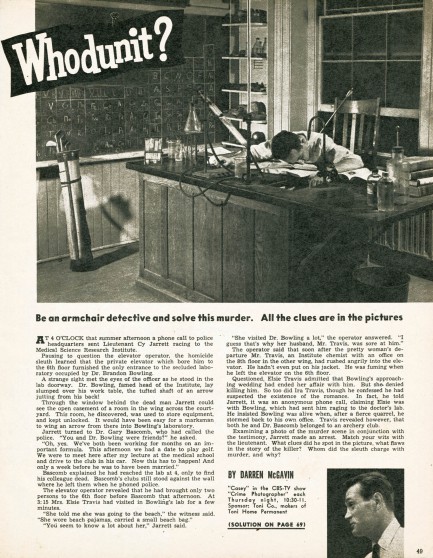

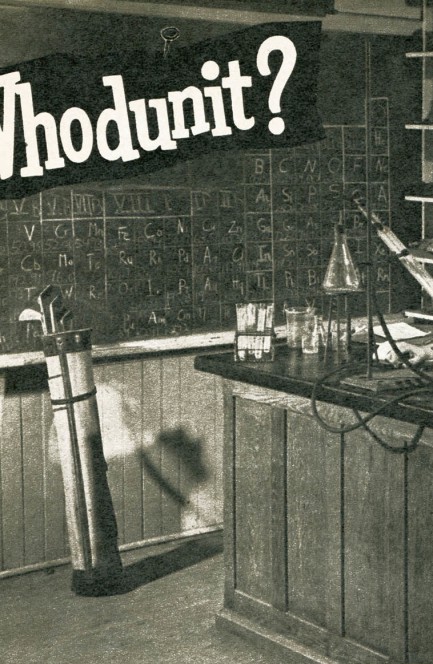

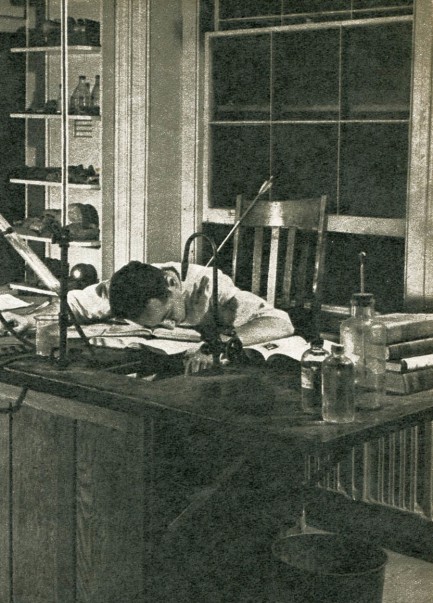

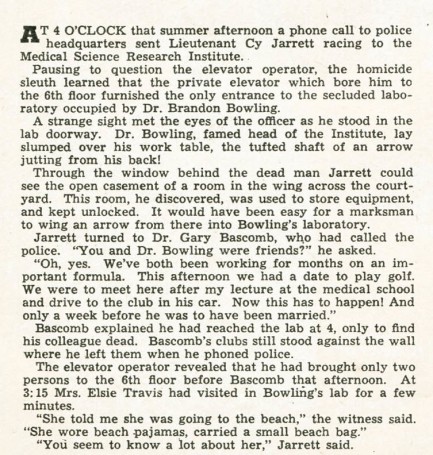

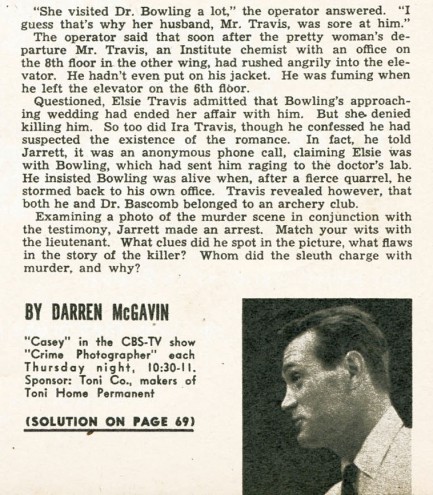

This issue of True Detective from June 1952 has cover art from Ozni Brown, along with all the standard crime magazine elements inside, but today we’re interested in its unusual solve-it-yourself murder feature. This is the first of these we’ve seen. A fictitious crime scene photo is published along with a short written scenario, and readers are invited to determine how the killing was committed and by which suspect. This particular puzzle is a television tie-in written by Darren McGavin, who at the time was starring in a CBS series called Crime Photographer. The show revolved around a world-weary crime tabloid photog narrating his latest adventures to his local bartender. The series lasted only forty-seven episodes, but McGavin would go on to star in other shows, including the beloved but also short-lived Nightstalker. If you want to take a crack at solving True Detective’s murder we’ve enlarged the relevant bits at the bottom of this post.

In order to make the whodunnit photo detailed enough we had to split it in half. It appears below along with the enlarged text.

And below is the solution.

| The Naked City | Feb 13 2015 |

When Mrs. Young came to retrieve her daughter, she found the church empty. She called the Scout leader and was told Janet never attended the meeting. This prompted a frantic call to the police, who quickly found the girl’s charred body. They arrested Ebbs at home hours later. The crime, once it hit the news, aroused a furious reaction in the community. Two civilian participants in a police line-up with Ebbs punched, kicked and spat on him. Though the police of course denied this assault ever happened, they put together an armed detachment of thirty-five men to forestall trouble at Ebbs’ arraignment. At his trial, which lasted eight days, four psychiatrists testified that he was legally insane, but four others pronounced him sane. He was convicted of first degree murder, and sentenced to life in prison. Ebb’s only reaction, at least according to accounts of the time, came when he saw the camera crews gathered to film him. He wondered aloud, “What will they think of me?”

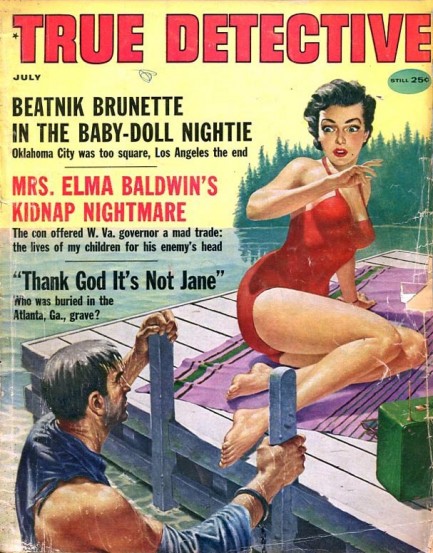

| The Naked City | Vintage Pulp | Jul 29 2014 |

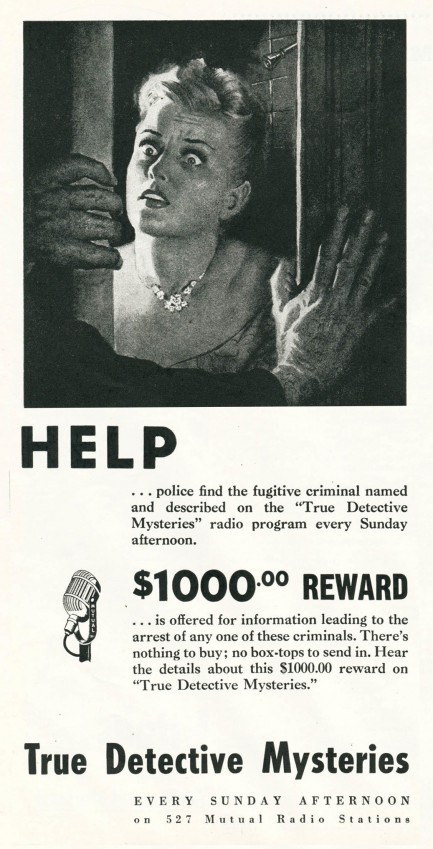

Above is a very nice True Detective from July 1959 with a Brendan Lynch cover depicting a woman startled by the arrival of a criminal. It’s actually a perfect cover, because inside the issue you get an interesting story related by Elma Baldwin, who was kidnapped by a paroled convict named Richard Arlen Payne. Payne snatched Baldwin and three her kids at gunpoint as part of an ill-conceived plan to trade them for the release of his former cellmate Burton Junior Post, aka Junior Starcher, who was serving time at West Virginia State Penitentiary in Moundsville. Payne didn’t want Starcher out because they were buddies. Quite the opposite—he had vowed to kill the man, and threatened to torture and murder the Baldwins if his demands weren’t met. He wrote in a note to Governor Cecil Underwood, “My purpose is to kill and take the head of my worst enemy, who is now out of reach. I must kill him or go mad.”

You’re probably asking why Payne never did anything to Starcher while they were cellmates. Payne’s  answer was simple: “I could have killed him at any time, and I thought about it very seriously. At times I had a blade to his throat. But he was as good as done for anyway, because I knew once I got in the free world there were ways that I could get at him.”

answer was simple: “I could have killed him at any time, and I thought about it very seriously. At times I had a blade to his throat. But he was as good as done for anyway, because I knew once I got in the free world there were ways that I could get at him.”

Well, maybe not so much. In any case, the kidnapping was big news in 1959, probably owing to its sheer incomprehensibility. Today it’s mostly forgotten but remains a good case study of the benefits of being able to let go one’s anger. The entire event lasted only twenty hours, ending with a brief shootout in which nobody was injured, followed by Payne’s admittance to a mental asylum. Asked if Starcher had done anything specific during their time at Moundsville to engender such hatred, Payne said, “Well, nothing I can put my finger on. It was just a sort of natural hatred.”

| The Naked City | Vintage Pulp | Dec 28 2013 |

True Detective gives readers the lowdown on several crimes in this issue published this month in 1958, but the most chilling story involves 18-year-old Marjorie Schneider, who was parked in a secluded lover’s lane near Fort Collins, Colorado with her date and another couple when she was abducted at gunpoint. True Detective scribe Jonas Bayer tells readers how the perpetrator was a man named Floyd Robertson, who first shot up the car, then robbed the quartet inside, and finally dragged the screaming Schneider away, saying, “I want the blonde to come with me.” With the car non-functional, the survivors ran two miles to a telephone. Their call touched off one of the largest searches in Colorado history. When police caught Robertson just days later, he admitted that he had abducted and raped Schneider, shot her three times in the head, then buried her body 600 feet up the side of an incline overlooking Highway 14. Robertson was later convicted of the crimes and sentenced to life in prison. The cover art on this issue is by Joe Little, who painted covers for Master Detective, Saga, Male, Man’s World, and many other mags. More from him later.

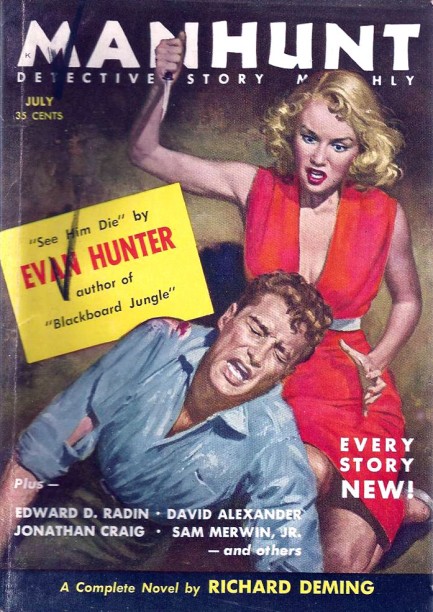

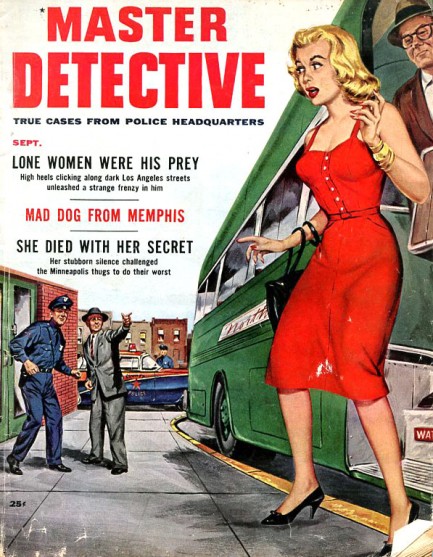

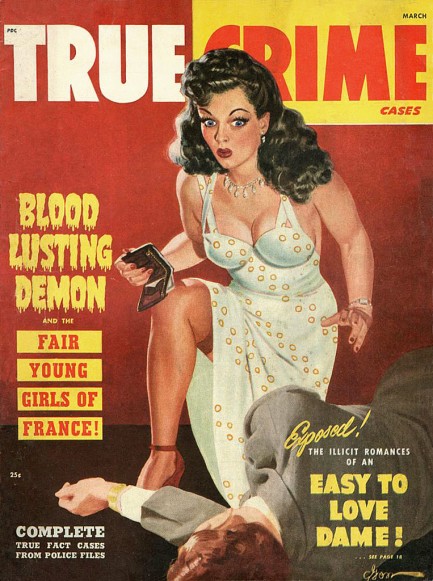

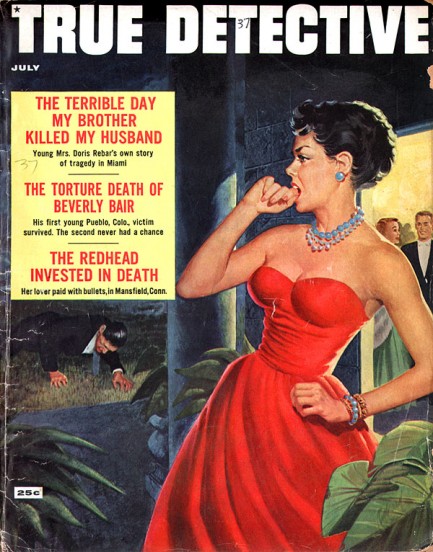

| Vintage Pulp | Feb 16 2013 |

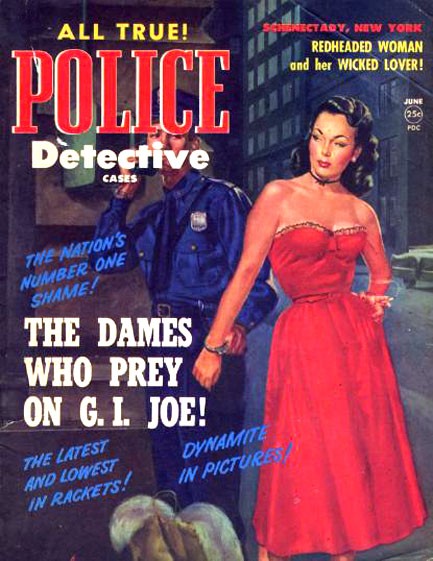

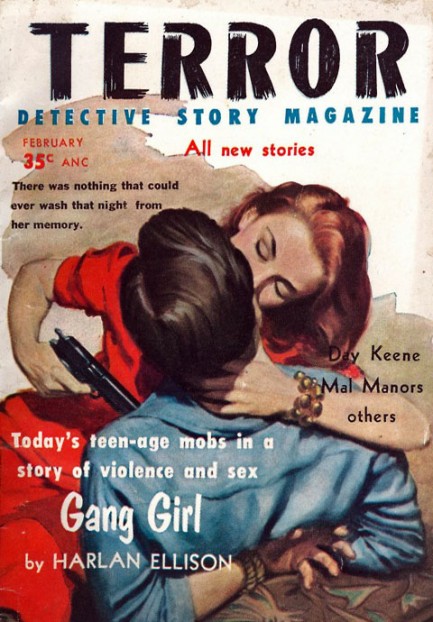

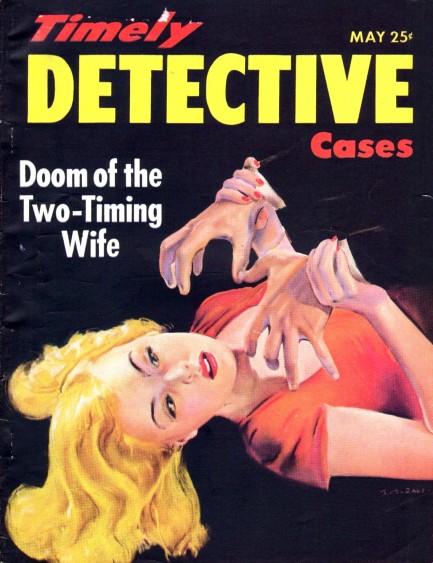

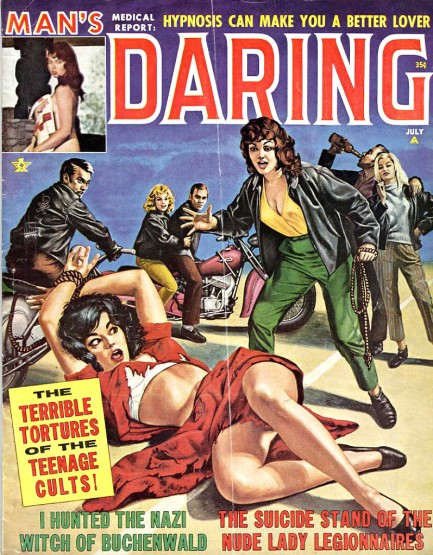

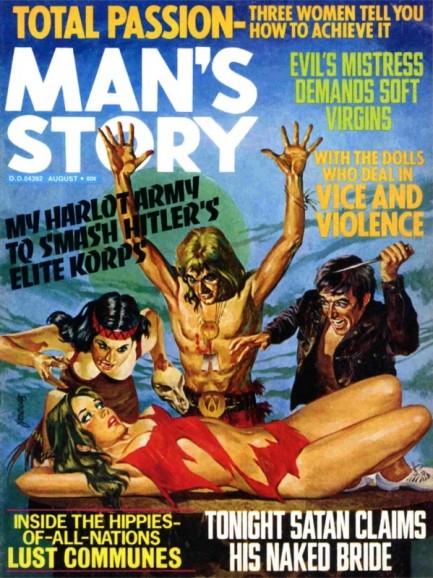

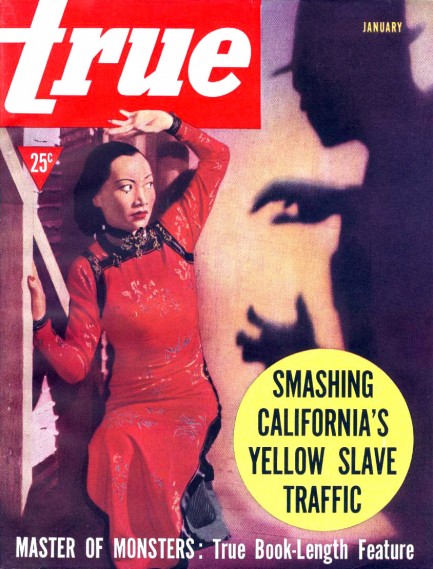

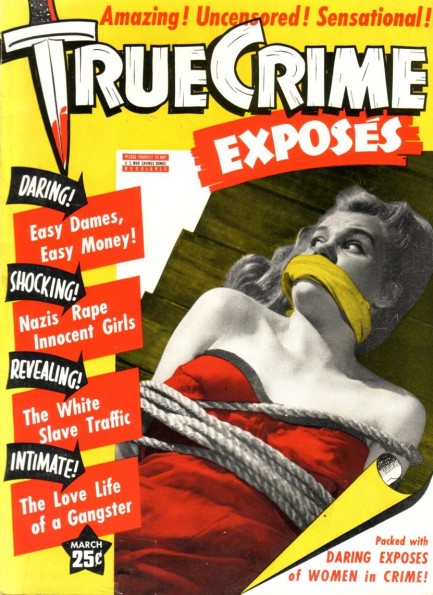

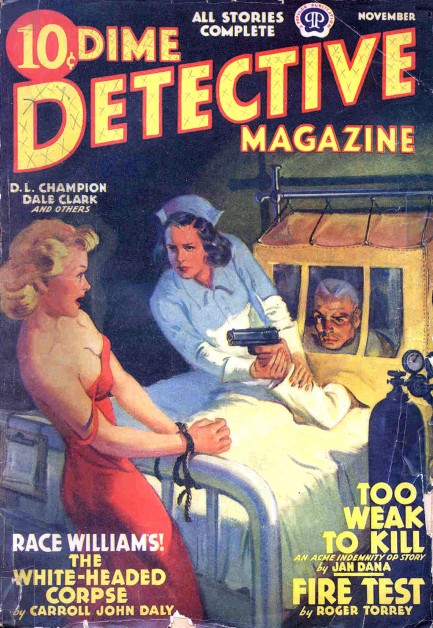

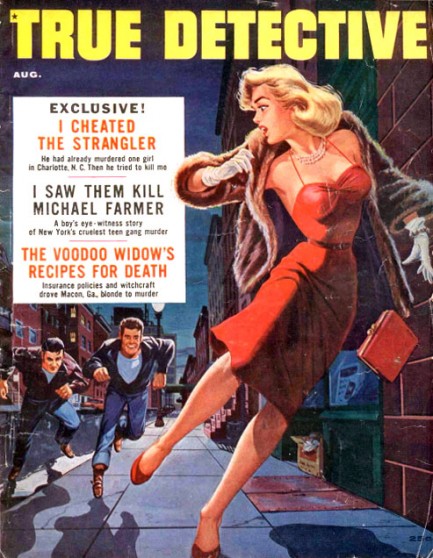

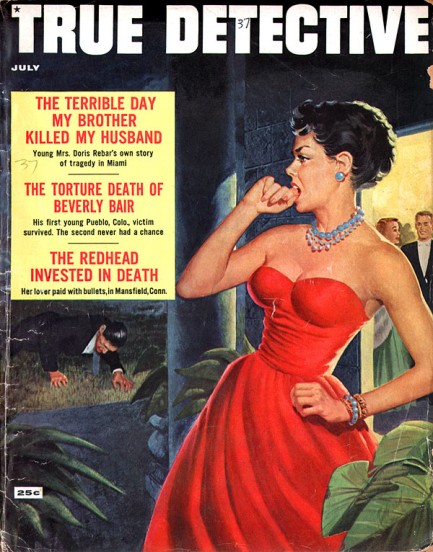

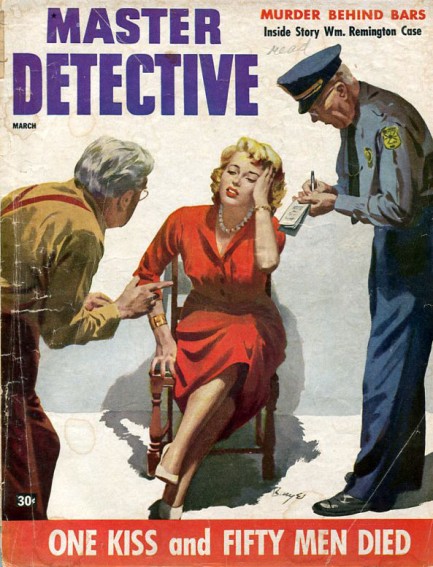

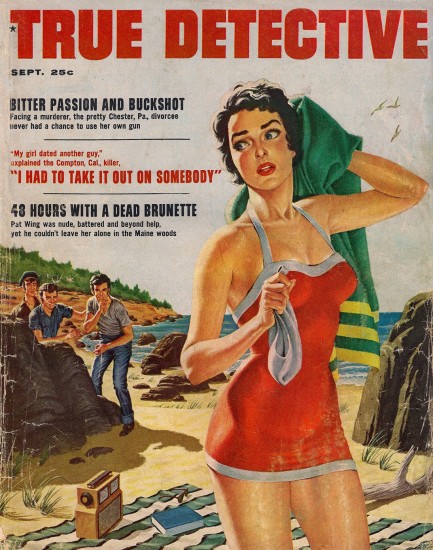

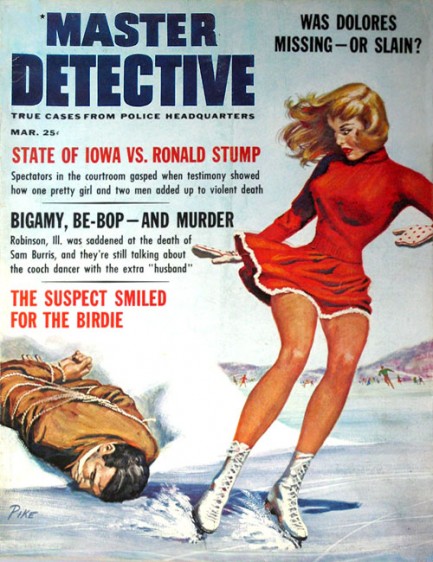

In fashion they say it takes a confident woman to wear a red dress. In pulp, it takes a woman with a death wish. Below are fourteen pulp, adventure, and detective magazine covers illustrating that point, with art by Bud Parke, George Gross, Barye Phillips and others, as well as a couple of photo-illustrations.

| Vintage Pulp | Sep 4 2012 |

| The Naked City | Jan 4 2012 |

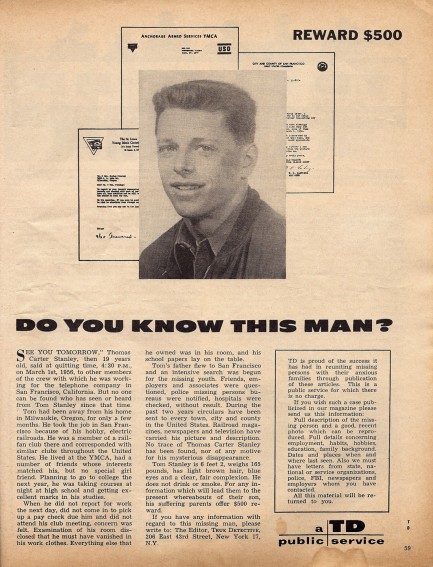

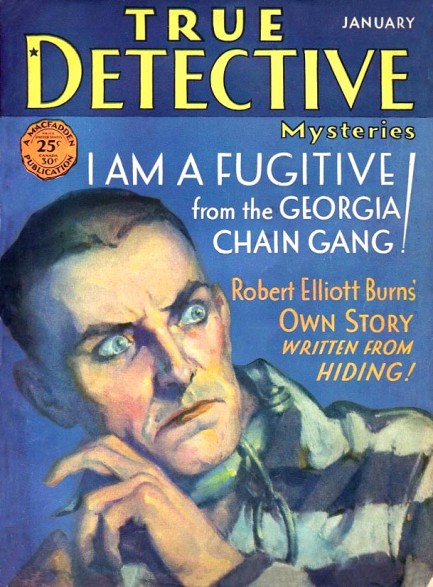

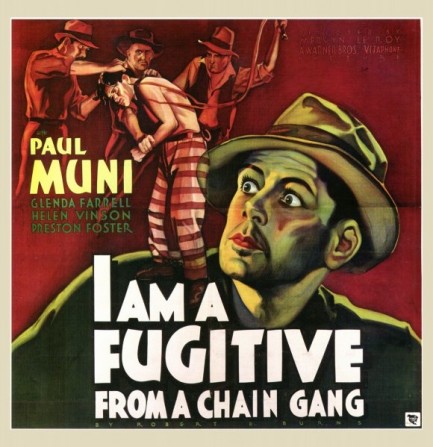

Dalton Stevens’ cover for this January 1931 issue of True Detective looks a bit like a horror illustration, but it's actually supposed to represent Robert E. Burns, who in 1922 helped rob a Georgia grocery, earned himself 6 to 10 at hard labor, but escaped and made his way to Chicago, where he adopted a new identity and rose to success as a magazine editor. Years later, when he tried to divorce the woman he had married, she betrayed him to Georgia authorities, and what followed was a legal battle between Georgia courts and Chicago civic leaders, with the former wanting Burns extradited, and the latter citing his standing in the community and calling for his pardon. Burns eventually went back to Georgia voluntarily to serve what he had been assured would be a few months in jail, but which turned into more hard time on a chain gang.

Angered and disillusioned, Burns escaped again, and this time wrote a book from hiding, which True Detective excerpts in the above issue and several others. This was a real  scoop for the magazine—it was the first to publish Burns’ harrowing tale. The story generated quite a bit of attention, and Vanguard Press picked it up and published it as I Am a Fugitive from a Georgia Chain Gang, which led directly to Warner Brothers adapting the tale into a hit 1932 motion picture starring Paul Muni. The movie differed somewhat from the book, of course, which differed somewhat from reality (Burns himself admitted this later), but his account cast a withering light on the chain gang system. The exposure helped chain gang opponents, who claimed—with some veracity—that the practice was immoral because it originated with the South's need to replace its slave labor after defeat in the U.S. Civil War.

scoop for the magazine—it was the first to publish Burns’ harrowing tale. The story generated quite a bit of attention, and Vanguard Press picked it up and published it as I Am a Fugitive from a Georgia Chain Gang, which led directly to Warner Brothers adapting the tale into a hit 1932 motion picture starring Paul Muni. The movie differed somewhat from the book, of course, which differed somewhat from reality (Burns himself admitted this later), but his account cast a withering light on the chain gang system. The exposure helped chain gang opponents, who claimed—with some veracity—that the practice was immoral because it originated with the South's need to replace its slave labor after defeat in the U.S. Civil War.

Burns continued to live life on the run, but was eventually arrested again, this time in New Jersey. However, the governor of the state refused to extradite him. The standoff meant Burns was, in practical terms, a free man. That practical freedom was made official in 1945 when he was finally pardoned in Georgia, and his literary indictment of the chain gang system helped bring about its demise. Well, sort of—it returned to the South in 1995, was quickly discontinued after legal challenges, but may yet be reintroduced as politicians push for more and more extreme punishments to bolster their tough-on-crime credentials.

| Vintage Pulp | Dec 1 2011 |

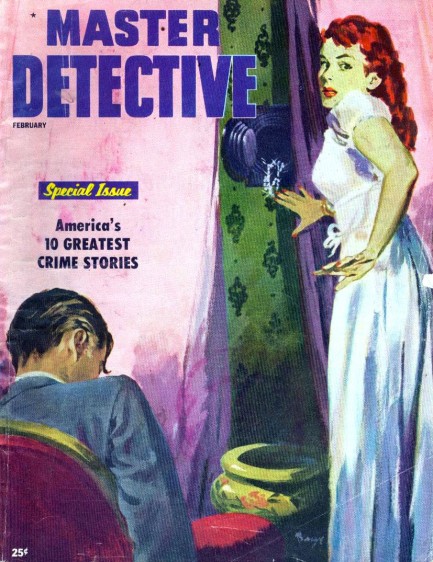

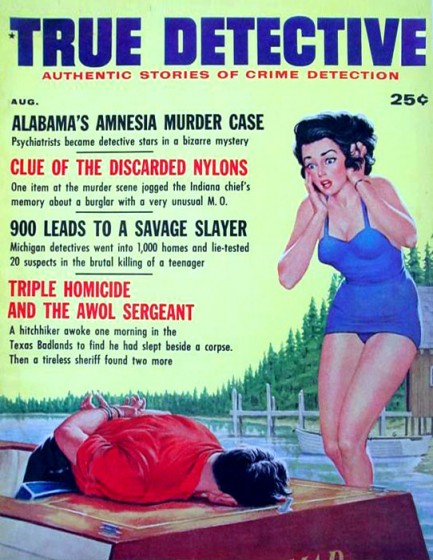

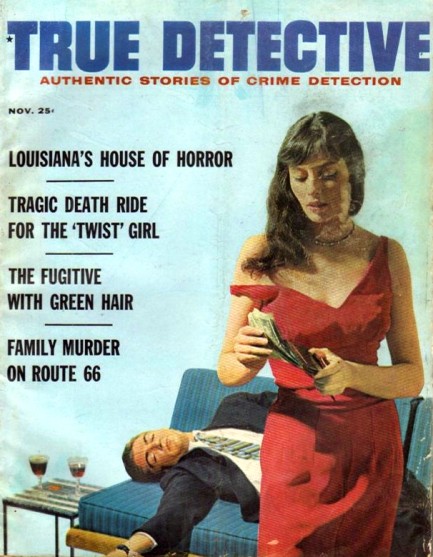

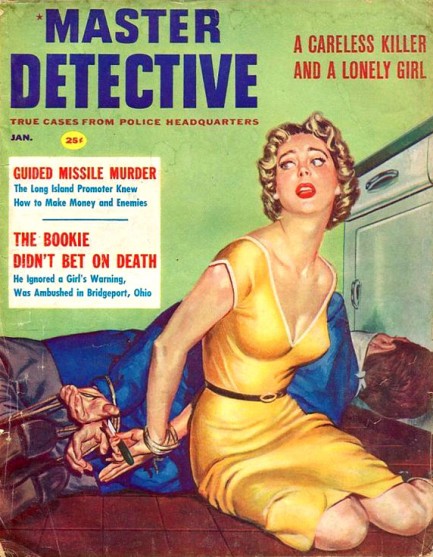

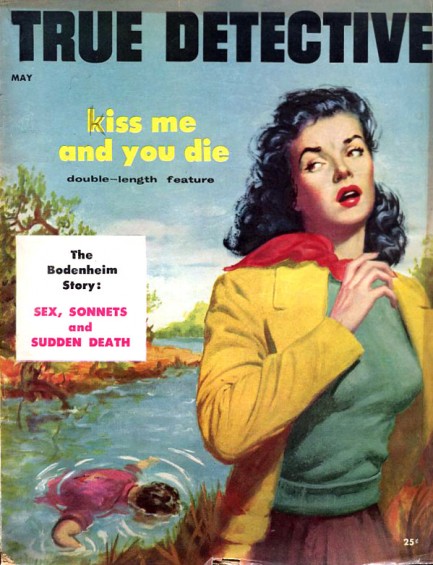

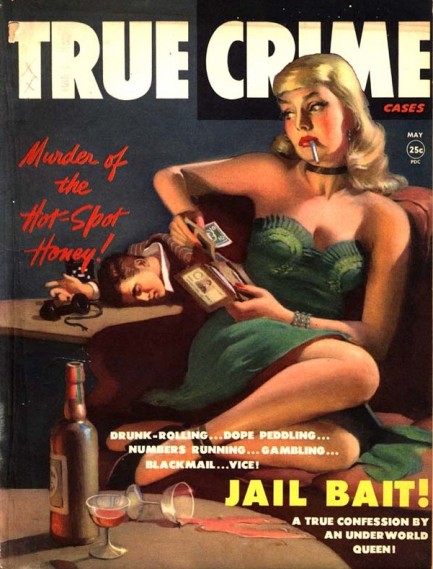

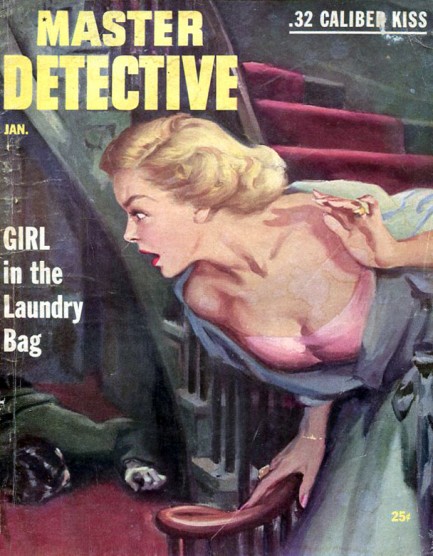

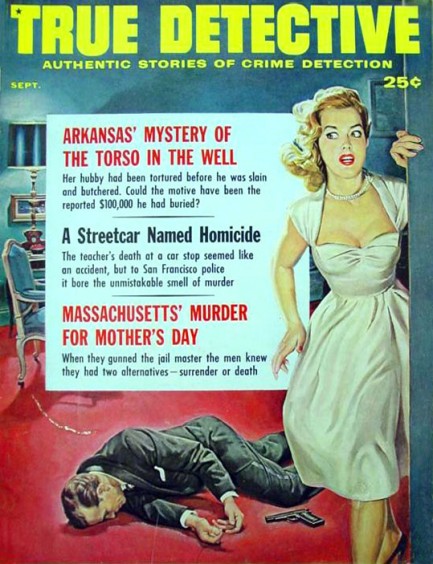

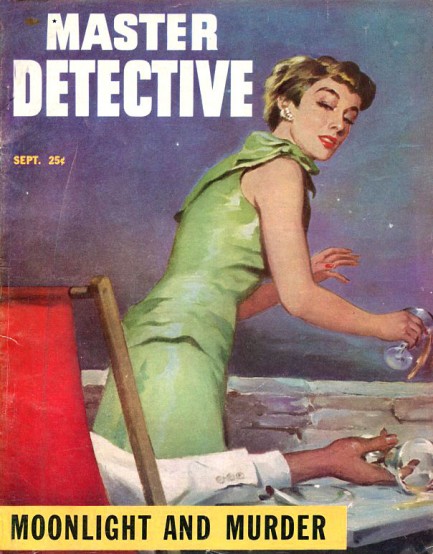

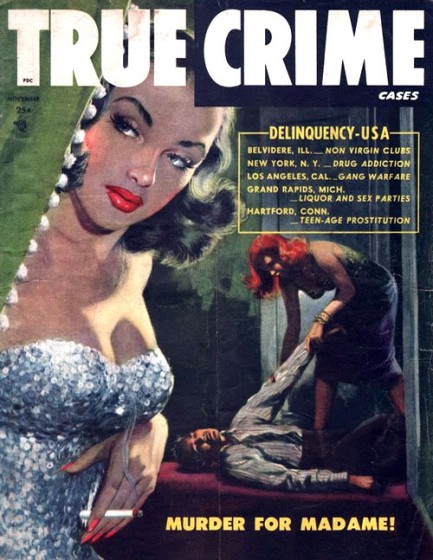

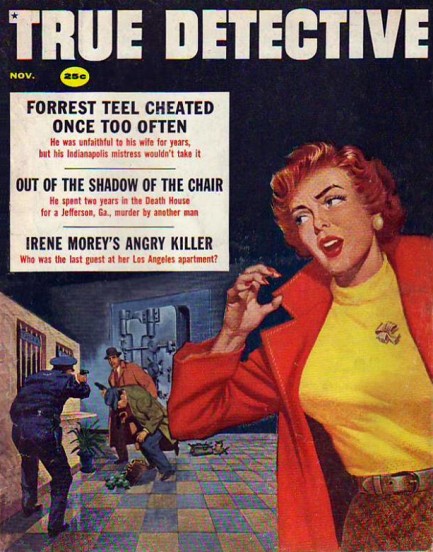

The woman who finds herself standing over a dead (or possibly drugged) man is a classic motif in true crime magazine cover art. Sometimes the woman is responsible for what's happened, while other times she simply has the bad luck to stumble into the situation. Covers of this type, you're probably already aware, fall under the category of Good Girl Art, with the “good” referring to the woman’s appearance, rather than her morals. Above and below are unlucky thirteen examples from mid-century crime magazines, with art from Barye Phillips, Jay Scott Pike, George Gross, Jack Rickard, and others. We borrowed one of these from Fringepop, and most of the rest we culled from online auctions where they’ve been languishing for months if not years. Feel inclined to collect a few classic true crime magazines? There are plenty of choices out there right now. Thanks to the original uploaders.

| The Naked City | Vintage Pulp | Nov 14 2011 |

Above is a cover of True Detective from November 1958 and inside is a story on the murder of Irene Morey, a Los Angeles woman who was found strangled along with one of her two young sons. The murder was eventually pinned on a gas station attendant named Charles Earl Brubaker who had met Morey a few days earlier when she had car trouble. Either in gratitude or because she was romantically interested in him, Morey invited him to her place for dinner a few nights later, and the date went wrong. When Brubaker was in the middle of choking the life out of Morey, the older of her two sons walked in, so Brubaker strangled him too. Brubaker confessed to the murders and was tried, convicted, and sentenced to death in the gas chamber. That sentence was later overturned by Judge Joseph A. Wapner (who would become famous on his 1980s television show The People’s Court), and instead of seeing the inside of the death chamber Brubaker served hard time until his parole in 1976. After his release he faded from public view, but his crime never will because its aftermath is part of the USC Digital Library’s collection of more than 200,000 Los Angeles Examiner negatives. Irene Morey and her son appear below, in life and in death. We highly recommend you take a spin around USC's Examiner collection. There’s more dark and forgotten history in there than you can imagine.