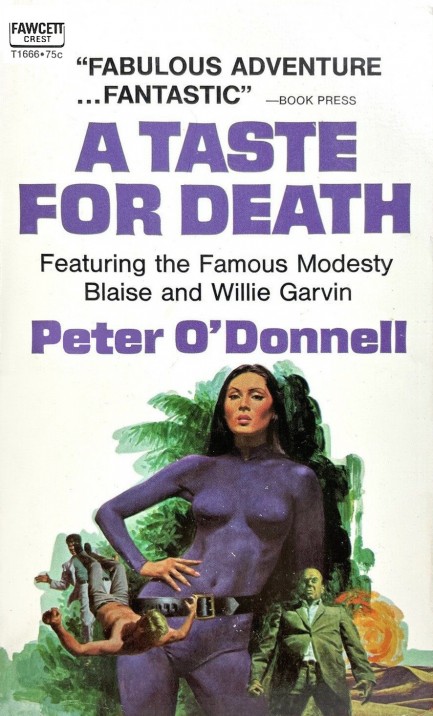

Modesty Blaise is mmm mmm good.

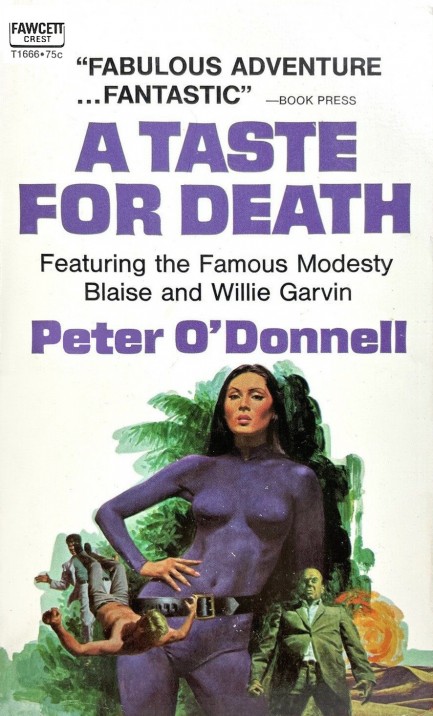

A Taste for Death was an entry in Peter O'Donnell's famed Modesty Blaise series, about an international criminal-turned-black ops death dealer. The previous three books featured Robert McGinnis fronts on the paperback editions, which you can see here, here, and here, but by the time this one appeared the paperback industry was shifting toward cheaper art—first photographic covers, and eventually computer graphics. The relentless pursuit of increased profits has cost society a lot, from beautiful urban cinemas to livable wages to entire forested mountaintops. Traditional paperback art isn't that important when measured against all the other losses, but it still represents the extinction of something enriching and fun. A Taste for Death was first published in 1969. This edition came from Fawcett Crest in 1972, with uncredited art which we consider to be the last painting of merit to appear on an English language Modesty Blaise paperback. More McGinnis pieces appeared on foreign editions, and we'll share those later. Also, some of the photo covers in the series are nice, and we may share those too.

The book brings back a villain Blaise and her sidekick Willie Garvin thought they had defeated in installment one, the nasty international jewel thief Gabriel, who this time is teamed up with a gorilla of a man named Simon Delicata in a plot to wrest the ancient and priceless Garamantes jewels from an Algerian archaeological dig. They've kidnapped Garvin's girlfriend Dinah Pilgrim, who can find precious metals and gems using dowsing rods and heightened senses. It's a typically imaginative set-up from O'Donnell, who we mentioned before creates villains fit for a James Bond movie. They're never just bad guys—they're freaks of criminality and terrifying physical specimens. Blaise and Garvin always have their hands full, and that's especially true in A Taste for Death, which features not only the wily Gabriel and the beast Delicata, but a master fencer named Wenczel eager to pincushion the heroes. We suggest you get a taste for Modesty Blaise. As fanciful spy capers go, her adventures usually hit the spot.

What a perfect day. It's days like this that make me glad we invested early in cryptocurrency and retired before thirty.

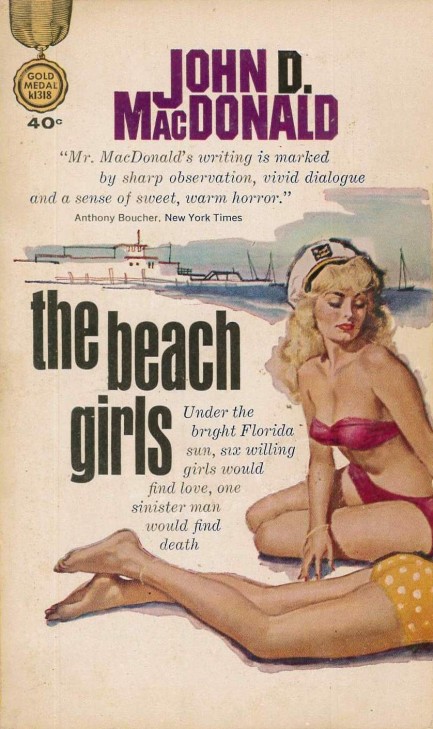

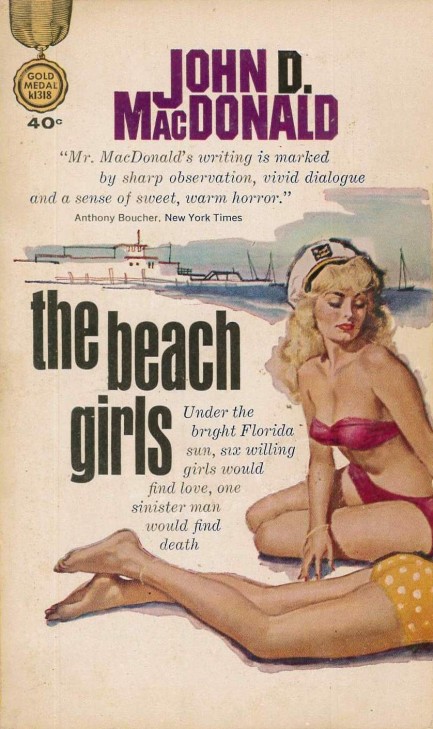

Above is a Charles Binger cover for John D. MacDonald's 1959 novel The Beach Girls. At this point, we know anything he wrote pre-Travis McGee is going to be good, and even the McGee books are mostly entertaining despite the main character's off-putting social judgments. The Beach Girls is a bit different from other MacDonalds we've read, largely written in a sort of round robin style where the final words of each chapter lead mid-sentence into the first words of the next, but with a change in first person point-of-view. The book cycles through numerous characters via this interesting trick before settling into standard third person narration for the finish.

The story deals with the inhabitants of a marina in fictional Elihu Beach, Florida, some of whom are friends, others enemies, some longtime residents, others newcomers, and how jealousy and resentment lead to a shocking act of violence. From the earliest pages you know this event is coming, and as the book wears on you become pretty sure who's going to be the unfortunate though deserving recipient, and who's going to be the giver. The main question becomes whether MacDonald will subvert these expectations and throw readers a curve. We'll just say it wasn't a predictable tale.

The only thing we don't get is why it's called The Beach Girls. The nearby beach area of the town is mentioned only a few times, no scenes are set there, and the book has an ensemble cast, with the women no more important than the men. There are groups of tourist women that pop up here and there, but they don't impact the story at all. Oh well. The title is a mystery, but an unimportant one. We'll get back to MacDonald a bit later. These 1950s efforts of his have been very worthwhile.

I have to admit, you're pretty good in the sack for a capitalist running dog lackey.

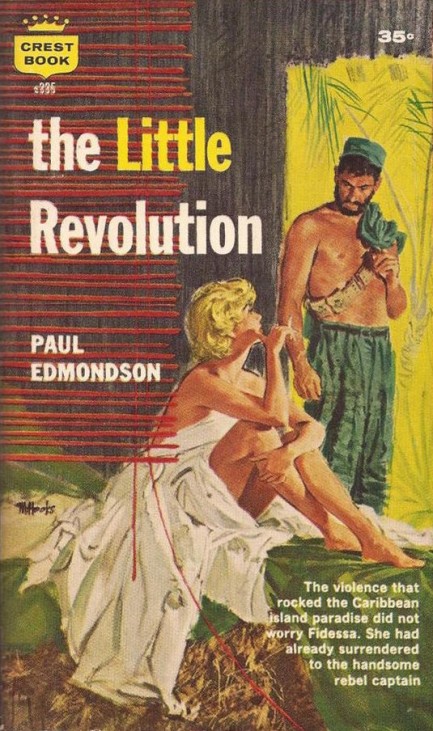

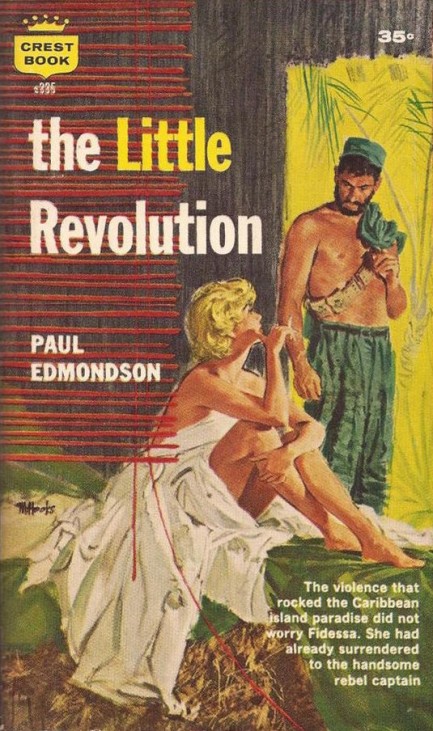

Heat, guns, passion, and politics. What more do you need for an adventure novel? Paul Edmondson's 1959 potboiler The Little Revolution is set on the fictional island of Caimanera, which is of course modeled after Cuba, where American wife Fidessa Broughton gets tangled up in a rebellion via her choice of a bedroom partner, even as her husband goes astray with a local woman, and a military captain's daughter rebels as well, in that way all teenagers do. The excellent art on this is by the eclectic Mitchell Hooks. We discussed his singular genius in detail a while back.

Your partners all voted and decided to demote you to this shallow grave.

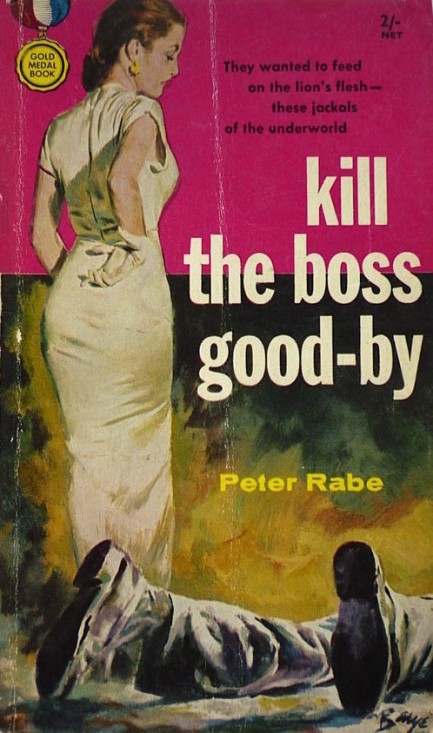

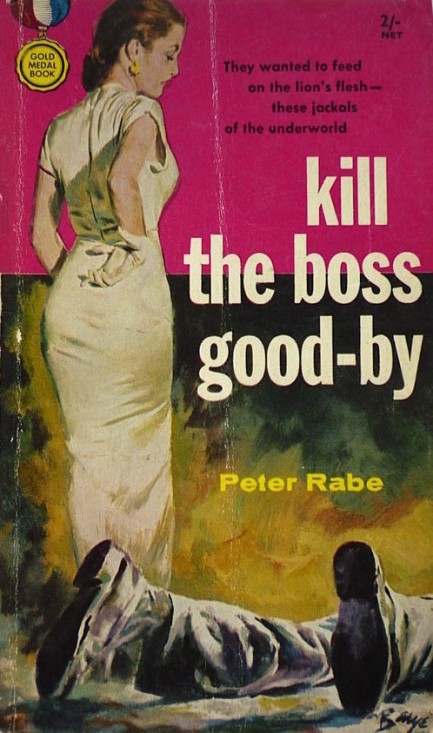

When the cat's away the mice will play, so the saying goes, and in Kill the Boss Good-By San Pietro crime kingpin Tom Fell goes missing for a month and a subordinate tries to take over his operation. When Fell reappears a power struggle ensues, while the top bosses in L.A. decide to wait and see who will come out on top. What makes the book a bit different is the reason Fell was missing—he was in a mental institution recovering from a breakdown with the aid of electroshock treatments. The new brain-scrambled Fell is calmer than the old Fell, but is he cured or is he worse? His enemies soon find out. Interesting hard boiled stuff from Peter Rabe, driven primarily by dialogue mixed with simple descriptive passages revealing a—dare we say it?—strong Hemingway influence. 1956 with cover art by Barye Phillips.

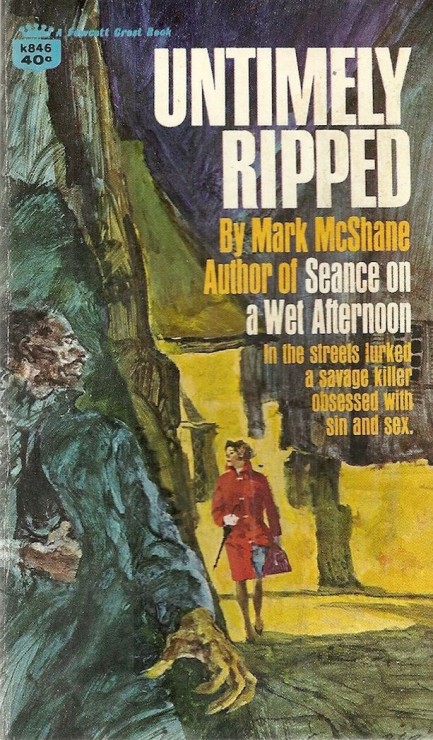

365 days in the year and just her luck she's in Greyton today.

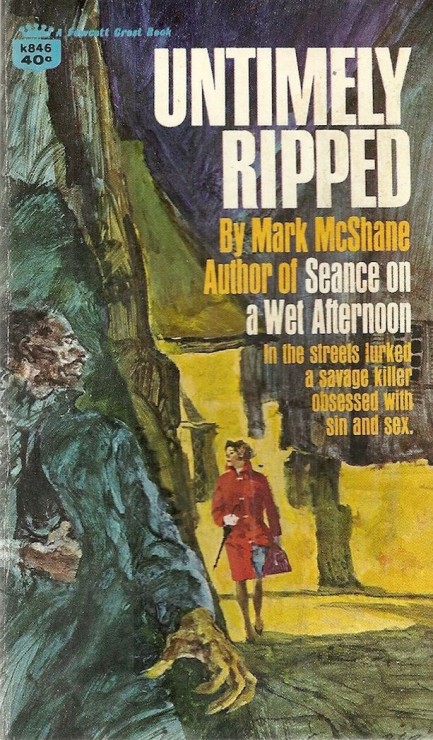

There's never an untimely moment for a great cover. This unusual piece fronts Mark McShane's Untimely Ripped, which as you can surely guess involves a Jack the Ripper type killer. The first victim in the fictional English village of Greyton is a prostitute, and the terror is due to the fact that in a place so small there are no strangers, which means the killer is someone known and loved—the priest, the constable, who knows? It gets worse. Not only is the killer seemingly someone they all know, but the first murder begins to look non-random when the victim's sister is killed and mutilated. Then a third victim suffers the same fate. We won't tell you more. Well, we'll tell you this: McShane uses the fifth longest word in the English language: praetertranssubstantiationalistically. What does it mean? Hah. Whatever he wants, because he made it up. The cover art on this Crest paperback is uncredited, which is a crime all its own.

|

|

The headlines that mattered yesteryear.

1985—Theodore Sturgeon Dies

American science fiction and pulp writer Theodore Sturgeon, who pioneered a technique known as rhythmic prose, in which his text would drop into a standard poetic meter, dies from lung fibrosis, which may have been caused by his smoking, but also might have been caused by his exposure to asbestos during his years as a Merchant Marine. 1945—World War II Ends

At Reims, France, German General Alfred Jodl signs unconditional surrender terms, thus ending Germany's participation in World War II. Jodl is then arrested and transferred to the German POW camp Flensburg, and later he is made to stand before the International Military Tribunal at the Nuremberg Trials. At the conclusion of the trial, Jodl is sentenced to death and hanged as a war criminal. 1954—French Are Defeated at Dien Bien Phu

In Vietnam, the Battle of Dien Bien Phu, which had begun two months earlier, ends in a French defeat. The United States, as per the Mutual Defense Assistance Act, gave material aid to the French, but were only minimally involved in the actual battle. By 1961, however, American troops would begin arriving in droves, and within several years the U.S. would be fully embroiled in war. 1937—The Hindenburg Explodes

In the U.S, at Lakehurst, New Jersey, the German zeppelin LZ 129 Hindenburg catches fire and is incinerated within a minute while attempting to dock in windy conditions after a trans-Atlantic crossing. The disaster, which kills thirty-six people, becomes the subject of spectacular newsreel coverage, photographs, and most famously, Herbert Morrison's recorded radio eyewitness report from the landing field. But for all the witnesses and speculation, the actual cause of the fire remains unknown. |

|

|

It's easy. We have an uploader that makes it a snap. Use it to submit your art, text, header, and subhead. Your post can be funny, serious, or anything in between, as long as it's vintage pulp. You'll get a byline and experience the fleeting pride of free authorship. We'll edit your post for typos, but the rest is up to you. Click here to give us your best shot.

|

|