New positions can really spice up your sex life. So can new species.

In the great state of Florida recently police were totally unsurprised when they uncovered a case of bestiality between a woman and a dog in Lee County, located in the southwest coast on the Gulf of Mexico. Samantha White, 26, was repeatedly recorded by her husband John, 29, as Samantha engaged in carnal acts with the canine, 4. The couple were outed after someone saw or became aware of videos posted online and notified local authorities. As mondo bizarro stories go, this one is out there. It's even weirder than that bag of random hands found in Russia a while back.

We picture the tawdry affair beginning by accident when Samantha mistook the dog for her husband, who looks sort of like a werewolf. She only realized her error when she and the dog got stuck together. John, who was busy in the back yard restoring his Camaro IROC-Z all this time, heard her screams for help, rushed into the house and separated the animal from his wife by throwing a bucket of cold water on their fused privates. That's the way it's said to work dog-on-dog, anyway, so why not dog-on-human? From that point we expect the Whites realized they enjoyed the weirdness of the episode—et voilà. A side hustle was born.

Unfortunately, putting videos of that type online will enrage and distress animal lovers, then likely come to the attention of police. “I am disgusted by the actions of these two residents,” commented one of the local lawmen. “I will not tolerate any kind of abuse.” Except, of course, abuse of civil rights. As a Florida law official he had to swear an oath on that. The dog, for his part, was removed to an animal shelter, and in a press conference admitted his guilt, profusely and convincingly. He's now negotiating a book deal.

It's amazing how fast calm can vanish at sea.

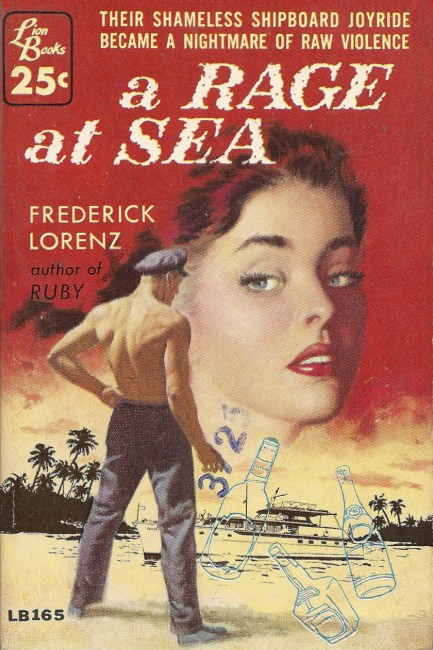

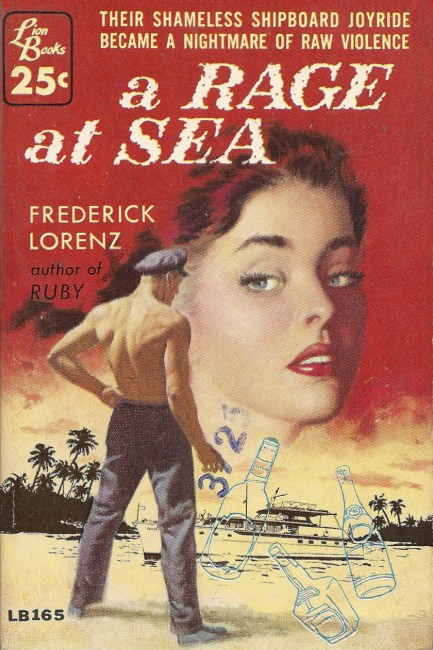

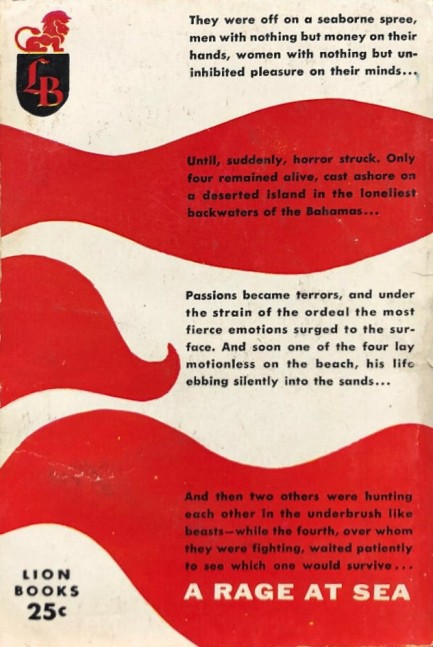

Though James Bama was a major illustrator, we haven't seen much of him here on Pulp Intl. over the years because he painted many fronts for western novels, and we rarely read those. This is his work on the front of Frederick Lorenz's 1957 thriller A Rage at Sea, the story of a down and out charter captain named Frank Dixon who's gone alcoholic after losing his beloved boat in a poker game. He's given a chance at redemption when he's offered a job captaining a yacht from Florida through the Caribbean.

The man paying for the boat is a philandering millionaire, and the person who recommended Dixon for the job is a dangerous and sneaky opportunist perfectly willing to admit that somehow this charter is supposed to lead to the millionaire being bled for his money. Any rational captain would refuse the job, but Dixon wants another boat and the pay he's being offered is a step along that path. It's also a step into a seagoing snakepit, and the situation goes from uncomfortable to terrible when he gets stuck in a life-or-death battle for survival.

We liked the book, but Lorenz does make a misstep or two. For example, there are seven people on the yacht, and while the engineer is an important secondary character, we never get to know—or for the most part even really meet—the other guests, which is a narrative choice we consider to be a flaw. Brushing off passengers in a closely confined yacht setting isn't realistic. But we get it—the story Lorenz wanted to tell is one of a man caught between a predator and victim, both of whom are awful people.

On the plus side, the book moves fast, the lines of conflict are propulsive and believable, and the setting and characterizations work. We'll look for more from Lorenz, who was really Lorenz Heller, and under the pseudonyms Lawrence Heller, Larry Holden, and Laura Hale authored intriguingly titled novels such as Hot, Night Never Ends, and A Party Every Night. Hopefully we'll get our hands on one of those and report back.

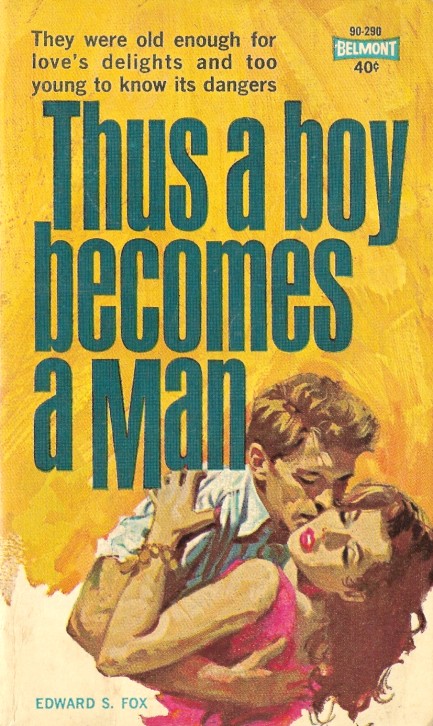

He's about to have a growth spurt.

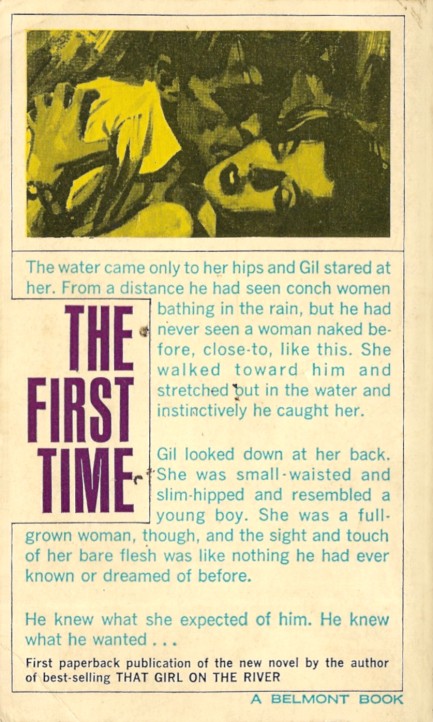

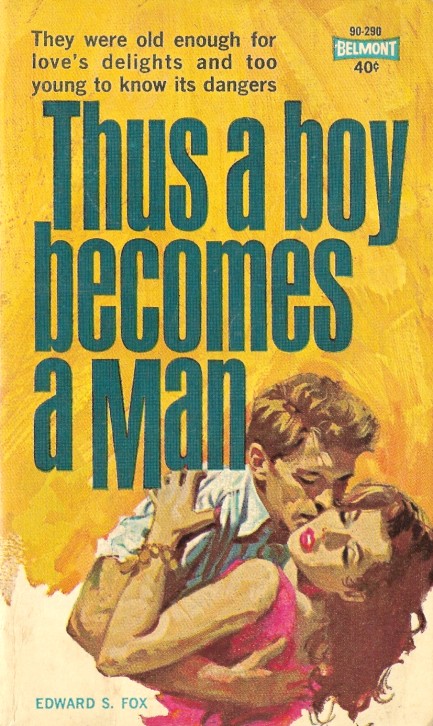

We were unable to learn who painted this Belmont Books cover for Edward S. Fox's 1963 novel Thus a Boy Becomes Man, but it's nice work, possibly a crop and zoom of a larger piece. We vacillated about buying it. We'd never read anything by or about Fox, and we weren't in the market for a simple romance or coming-of-age novel, but in the end we took a flyer, the international mails operated without problems, and the book appeared at our door. It turned out to be a short novel, brief enough to be knocked off in an afternoon, but despite its brevity it was a tale we enjoyed.

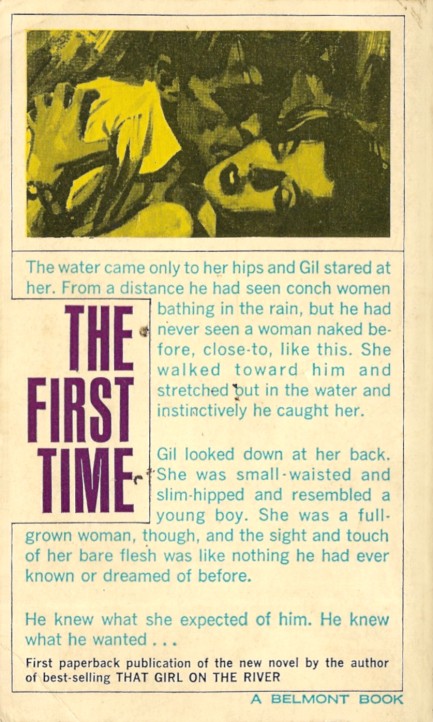

The protagonist is young Gil Stuart, who has no experience with women, until two appear in his neck of the Florida Keys—teenaged Georgette and twenty-ish Christine. Georgette is a new Florida resident who lives on a nearby key, while Christine is a seasonal arrival, daughter of a rich Boston railroad executive heading up a project. Both girls are pretty, and both fall for Gil, but he's resistant to them, mainly because he lacks acuity in sexual matters. For that reason, though he's in his early twenties, he feels more like a mid-teen, like a sixteen-year-old. And for that reason, it feels like Fox was shooting for a subtropical Holden Caulfield.

Any book set in the Florida Keys has to be concerned with real estate, seemingly, and this one has a parallel plot about the building of a rail line cutting off bay drainage and subjecting residents to catastrophic flood peril. When appeals to the railroad company yield nothing, some of the conchs decide, as hurricane season approaches, to dynamite the embankment being built for the train tracks. This is a compelling backdrop for Gil's story, as both plot threads suggest that the future—whether bringing romance or trains—is inevitable. Subtle? Maybe not. But it basically worked, faux Caulfield and all.

I take it from the way you're sprawled across the front seat that dinner and a movie is no longer the plan.

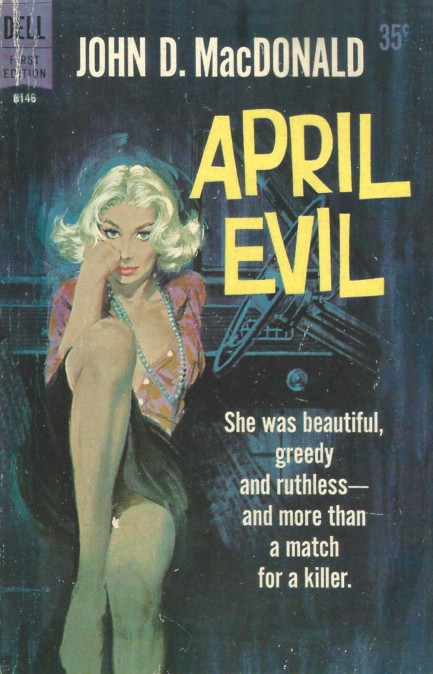

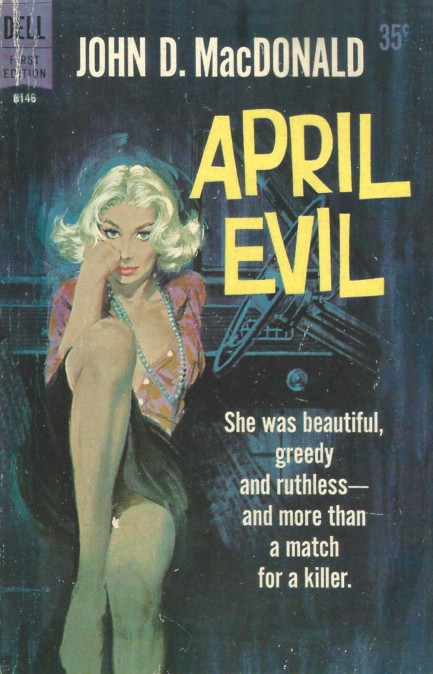

April Evil is a book that showcases John D. MacDonald on literary cruise control, as he confidently weaves together the tale of an elderly, widowed ex-doctor whose has a safe in his study filled with cash, the greedy relatives that hope he leaves his loot and property to them, and how, because rumors of the money have spread, three criminals decide to rob his house. Matters are even more complicated because the doctor has taken in a young married couple, and while the wife is not scheming to get his fortune, the husband is, and he has a big mouth. That mouth entices a psychopathic killer into hijacking the robbery scheme, with the ultimate plan of killing both his partners and—probably—everyone living in the house. For people acquainted with MacDonald but who haven't read April Evil, the approach will be familiar, particularly the character crosscurrents and fateful timing. It's well written, enjoyable, and free of pseudo-sociological content, which we consider to be a problem with McDonald's Travis Magee novels. We recommend it, even more so if you can score Dell's 1956 edition with Robert McGinnis cover art.

Lines in the sand have a way of getting crossed.

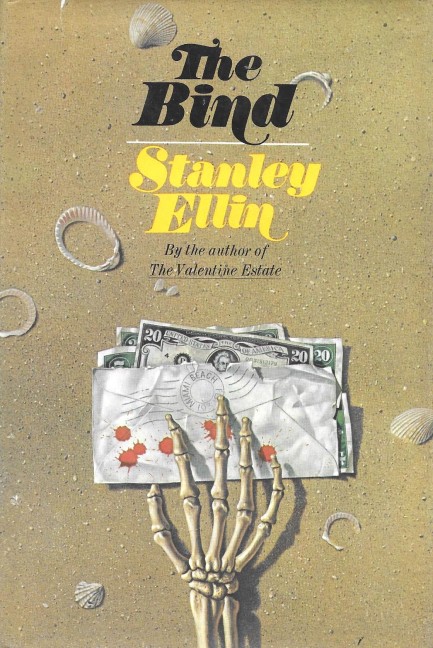

Considering our website's focus on beautiful art, you must be asking how we came to read Stanley Ellin's 1970 novel The Bind, with its beige post-GGA cover treatment by Joe Lombadero. What happened was we decided to watch the 1979 Farrah Fawcett movie Sunburn, but stopped during the opening credits when we saw that it was based on a novel. We'd decided to see the movie because it was helmed by cult director Richard C. Sarafian, and also because its premise interested us, but we figured that premise was probably more fully and interestingly developed in the source novel. We won't know for sure until we watch the film, but it's pretty much a given when you compare literature to cinema.

Here's the premise: insurance investigator Jake Dekker needs to get close to a secretive family to disprove a verdict of accidental death and save his employers a $200,000 payout, so he rents a house in their tony Miami enclave and hires an actress to pose as his wife. The family would be suspicious of a single man, but not a married couple. He's carried out similar scams and worked with the same actress over and over, but when she can't make the gig she instead sends down-on-her-luck colleague Elinor Majeski as a replacement. The fake wife aspect of Jake's scheme immediately gets complicated, both because this new actress is smarter and more curious than is convenient, and because she's unusually lovely. Uh oh. Professional comportment—out the window.

Ellin pushes his ripe premise for all it's worth. Jake insists on realism, which involves he and Elinor getting comfortable around each other, whatever intimate circumstances might arise. The only line they aren't to cross is sleeping in the same bed. Heh. How long do you think that lasts? Actually, it lasts a long while. Jake's shell is hard. He's borderline mean to Elinor, and therein lies the balancing act in the narrative. He's mean, but occasionally charming. Ellin's writing treads that crucial line well, but the book is overlong and its climax goes in a direction we didn't like. But we'd read him again. In any case, now we'll have to see what the filmmakers did with Farrah in the role of Elinor. Charles Grodin co-stars, so we expect the movie to be a bit silly, but who can resist Farrah?

What! A big bubble? Well, yours looks like five pounds of potatoes in a ten pound sack!

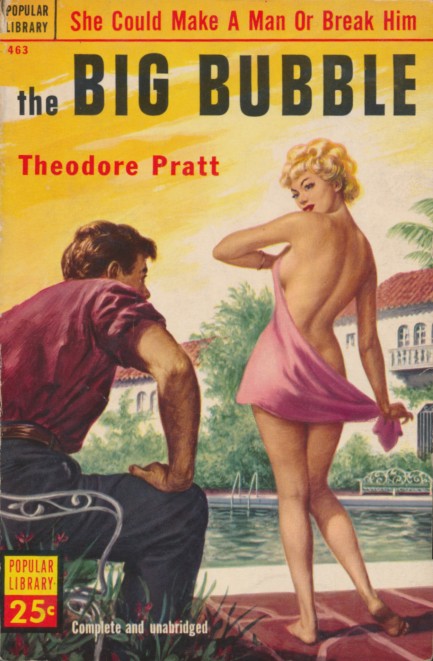

It seems like Florida novels are a distinct genre of popular fiction, and most of the books, regardless of the year of their setting, lament how the state is being drawn and quartered in pursuit of easy money. But those complaints are usually just a superficial method of establishing the lead characters' local cred. Theodore Pratt, in his novel The Big Bubble, takes readers deep inside early 1920s south Florida real estate speculation in the person of a builder named Adam Paine (based on real life architect Addison Mizner), who wants to bring the aesthetic of old world Spain to Palm Beach—against the wishes of longtime residents.

Paine builds numerous properties, but his big baby is the Flamingo Club, a massive hotel complex done in Spanish and Moorish style. He even takes a trip to Spain to buy beautiful artifacts for his masterpiece. This was the most interesting part for us, riding along as he wandered Andalusia (where we live), buying treasures for his ostentatious palace. He buys paintings, tapestries, sculptures, an ornate fireplace, an entire staircase, basically anything that isn't nailed down, even stripping monasteries of their revered artifacts. His wife Eve is horrified, but Paine tells her he's doing the monks a favor because they'd otherwise go broke.

You may not know this, but Spain is pretty bad at preserving its ancient architecture. That's another reason The Big Bubble resonated for us—because Spain is very Floridian in that it's being buried under an avalanche of cheap, ugly developments. We love south Florida's Spanish revival feel. What's metastasized in Spain is a glass and concrete aesthetic that offers no beauty and weathers like it's made of styrofoam. The properties are basically glass box tax dodges. The point is, reading The Big Bubble felt familiar in terms of its critique of real estate booms, but simultaneously we saw Paine as a visionary. He made us wish Spanish builders had a tenth of his good taste.

Since the book is set during the 1920s (and its title is so descriptive) you know Florida's property bubble will burst. Paine already has problems to deal with before the crash. Pratt resolves everything in interesting fashion. He was a major novelist who wrote more than thirty books, with five adapted to film, so we went into The Big Bubble expecting good work, and that's what we got. And apparently it's part of a Palm Beach trilogy (though he set fourteen novels in Florida total). We'll keep an eye out for those other two Palm Beach books (The Flame Tree and The Barefoot Mailman). In the meantime, we recommend The Big Bubble. Originally published in 1951, this Popular Library edition is from 1952 with uncredited art.

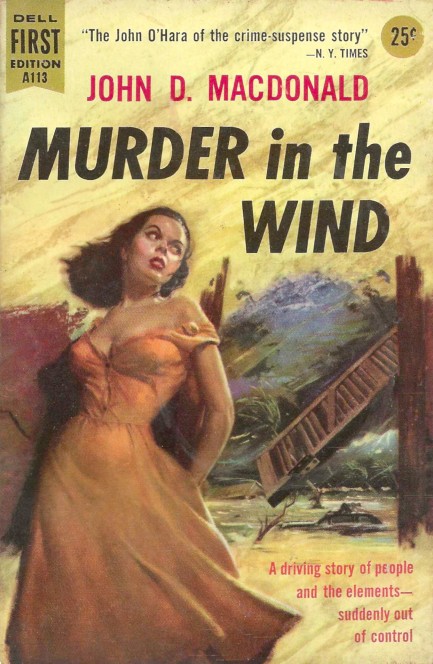

Southwest Florida gets obliterated but most of the wreckage is human in MacDonald disaster drama.

The three weather based thrillers we've discussed—A Town Is Drowning, Tropical Disturbance, and Death at Flood Tide—represent a minor fraction of the total in mid-century fiction. It's no surprise, then, that an author as prolific as John D. MacDonald also tested the waters. Murder in the Wind, also known as Hurricane, came in 1956 during the more fertile, less censorious period for MacDonald, and presents readers with a disparate selection of people who all hole up in an abandoned house during a hurricane named Hilda. Eventually the house is swept away entirely, but the story is never less than solidly grounded and engrossing. If your time is limited you might skip this one in favor of The Damned, which is a close cousin, conceptually speaking, but otherwise Murder in the Wind is a necessary read. You get all the fulfillment you'd want from a disaster drama.

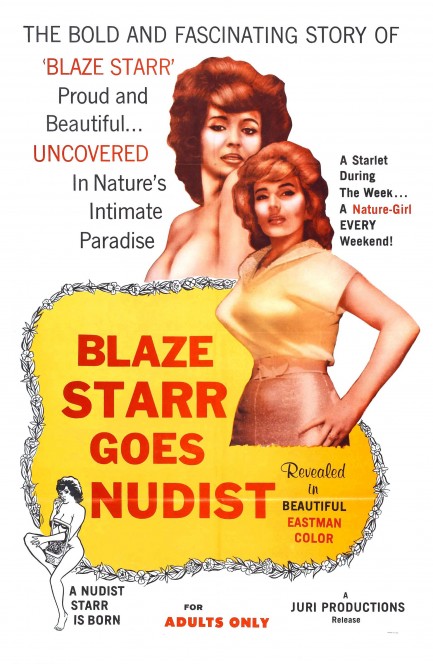

Burlesque sensation Blaze Starr takes the obvious next step in nudity related activities.

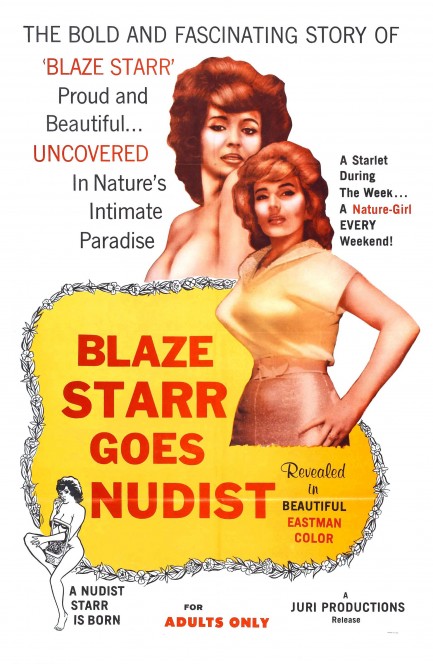

Blaze Starr was one of the most famous burlesque dancers of the mid-century era thanks to both her on- and off-stage activities. She began headlining in clubs during the early 1950s, soon earned the sobriquet “The Hottest Blaze in Burlesque,” and later became not just famous, but infamous, due to having embarked on a tempestuous affair with Louisiana’s impulsive governor Earl Long, who she was still seeing when he died of a heart attack in 1960. Above is a promo poster for Blaze Starr Goes Nudist, which premiered today in 1962, well after Starr had become a household name.

In the film, Blaze, who plays a mainstream actress rather than a stripper, decides she needs a break from her demanding career and busy public life. She decides to spend weekends at the Sunny Palms Lodge in Homestead, Florida in order to enjoy a little nude rest and recreation under the phony name Belle Fleming. Her sinister looking agent/fiancée is apoplectic about this, but he'd be really annoyed if he knew Starr and the camp administrator were making googly eyes at each other. Aside from flirting, Starr indulges in the usual nudist colony activities—sunbathing, archery, dozing in a hammock, tiptoeing around the communal pool, taking romantic walks in the mosquito infested woods, and listening to some schlub play an accordion.

Forget anything resembling acting ability here—everyone is atrocious, and Starr is worst of all. The blame may not be entirely hers, though. The movie was obviously made fast and cheap, and it was directed by Doris Wishman, who helmed such epics as Nude on the Moon and Bad Girls Go to Hell, and is considered by some to be one of the worst practitioners of her craft ever. But we all know the movie is simply meant to be eye candy. On that score it works. Considering the unflattering range of bodies possessed by normal humans, it's clear that most of the female nudists involved in this production are models, and probably some of the males too. Starr looks pretty good herself, even with her wonky boobs and ridiculous helmet of flaming red hair.

The movie is meant not only to display Starr, but to espouse and promote the nudist lifestyle—and really, considering that there's a little plug for Sunny Palms at the outset, it could actually be considered a long form advertisement for the colony. We bet the membership—so to speak—really expanded—so to speak. We can't say Blaze Starr Goes Nudist is a good movie, but it's totally harmless and infectiously fun. There can never be too much of those things in the world. You can see more of Starr at the bottom of this post, and you can see a fascinating piece of Starr memorabilia here (sent to us by a reader way back before our Reader Pulp uploader bit the dust).

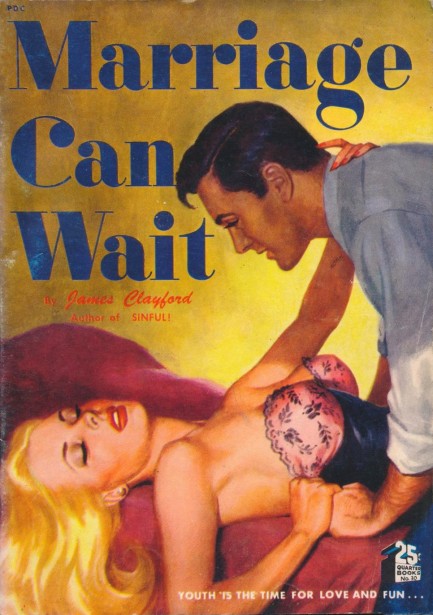

I agree we should put off getting married. For one thing, we'd both have to get divorces first.

We've said it before—you never what you're going to get when you buy vintage paperback digests. The cover art, as in the case of James Clayford's 1949 novel Marriage Can Wait, often has nothing to do with the content. This looks straightforward but it's one of the stranger tales you'll come across. It was written by Peggy Gaddis under her Clayford pseudonym, and it's about a hard partying yacht trip from New York City to Jacksonville, peopled by six jet-set types and one everyman named Tony Ware. As the only unwealthy person aboard aside from the crew, Tony takes it badly when the yacht's owner Elaine Ellison jilts him one night. She'd invited him to her cabin for nocturnal fun, but he arrived to find another man there. In embarrassment and disgust he jumps overboard and swims ashore. He thinks he's swimming to the Florida mainland. He actually ends up on an island nudist colony. He's horrified, but since supply boats come only once a month the only way he can eat is to doff his garments and join the colony. And it's there that he finds true love in the form of Eve Darby.

Tony's yachting pals, who are habitually hungover each day, assumed he'd abandoned them in port one morning and they'd simply slept through it. Nobody is concerned except Elaine, who realizes she behaved terribly toward him. Weeks later they sail to the nudist island thanks to a bizarre subplot that has them half-jokingly searching for Blackbeard's buried treasure. They don't know the place is inhabited, but they soon find out, and can only stay if they agree to become nudists, which Elaine and her five idle rich friends do in order to secretly search for the treasure. They of course find the long lost Tony, and Elaine is ashamed at how she treated him, then smitten as she realizes she loves this newly bronzed hunk. The only way to try and win him over is to stay at the colony—plus the treasure might be there too—so she settles in for an extended nude sojourn. We'll stop the synopsis there except to say that you have to give Gaddis major points for creativity. The cover art, by the way, is uncredited.

|

|

The headlines that mattered yesteryear.

2003—Hope Dies

Film legend Bob Hope dies of pneumonia two months after celebrating his 100th birthday. 1945—Churchill Given the Sack

In spite of admiring Winston Churchill as a great wartime leader, Britons elect

Clement Attlee the nation's new prime minister in a sweeping victory for the Labour Party over the Conservatives. 1952—Evita Peron Dies

Eva Duarte de Peron, aka Evita, wife of the president of the Argentine Republic, dies from cancer at age 33. Evita had brought the working classes into a position of political power never witnessed before, but was hated by the nation's powerful military class. She is lain to rest in Milan, Italy in a secret grave under a nun's name, but is eventually returned to Argentina for reburial beside her husband in 1974. 1943—Mussolini Calls It Quits

Italian dictator Benito Mussolini steps down as head of the armed forces and the government. It soon becomes clear that Il Duce did not relinquish power voluntarily, but was forced to resign after former Fascist colleagues turned against him. He is later installed by Germany as leader of the Italian Social Republic in the north of the country, but is killed by partisans in 1945.

|

|

|

It's easy. We have an uploader that makes it a snap. Use it to submit your art, text, header, and subhead. Your post can be funny, serious, or anything in between, as long as it's vintage pulp. You'll get a byline and experience the fleeting pride of free authorship. We'll edit your post for typos, but the rest is up to you. Click here to give us your best shot.

|

|