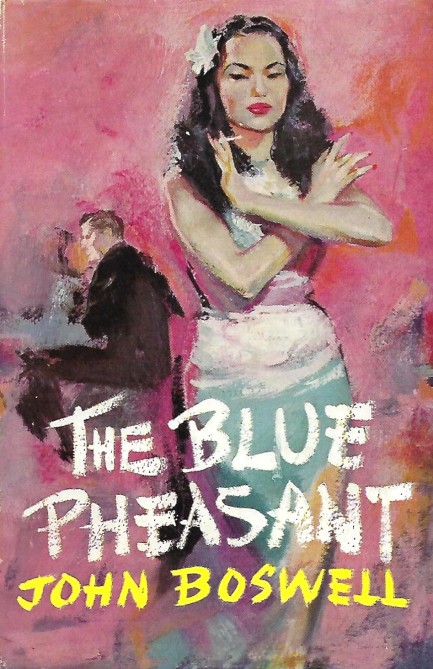

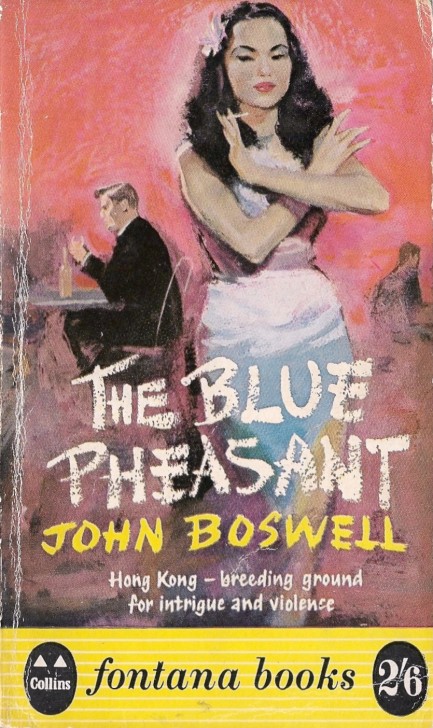

She makes sure a Pheasant time is had by all.

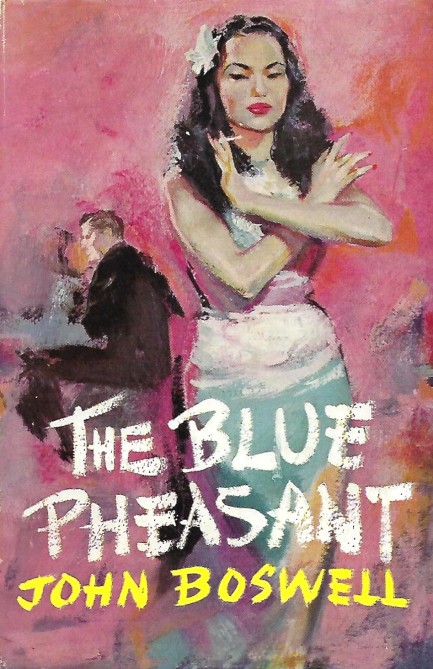

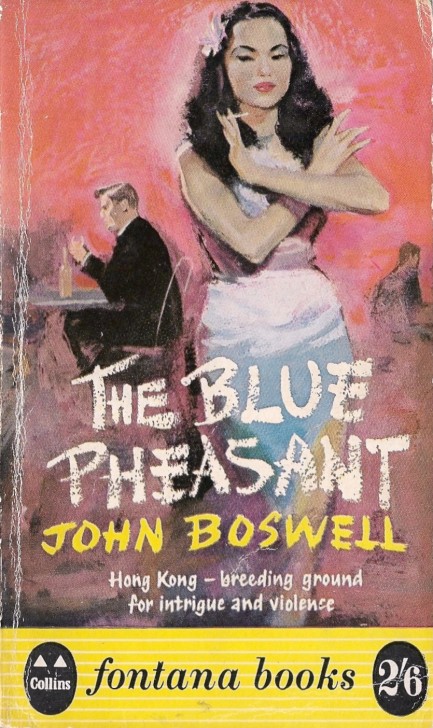

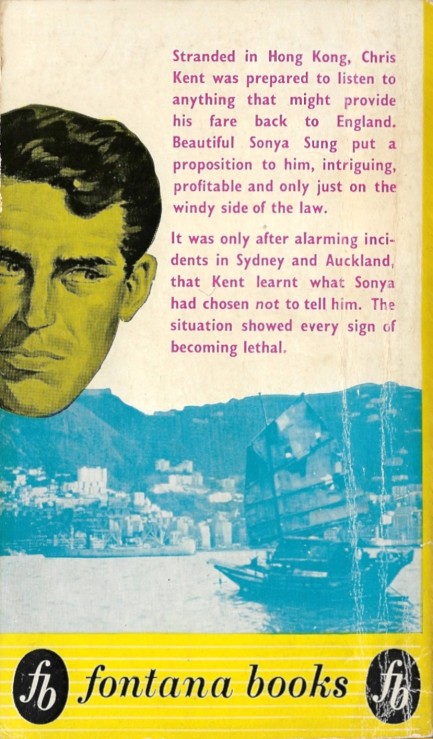

We were attracted to the 1958 John Boswell thriller The Blue Pheasant not only because of the lovely cover art, and the tale's setting in East Asia and New Zealand, but because the title suggests that a bar plays a central role. We always like that, whether in fiction or film. The teaser text confirms it. The title refers to a fictional bar in Hong Kong. Irresistible. The book stars professional photographer, amateur painter, and rolling stone Chris Kent, who's at desperate ends and takes a job to travel from Hong Kong to far away Auckland to recover two Chinese scrolls that are the keys to a vast inheritance. Needless to say, there are other interested—and ruthless—parties. In addition there are three femmes fatales: Sally Chan, the bar dancer who puts Kent onto the job; Sonya Sung, whose family are the rightful owners of the misplaced scrolls (or are they?); and Ann Compton, mystery woman who becomes Kent's reluctant partner.

We were amused by how easily Kent's head was turned by all three women. He's tough, but he's also an all-day sucker. In trying to sort out why women are so confounding to him, there are numerous moments of, “Well, what's a guy to do when women are ________” By the end, though, he starts to wonder if he's the problem. Spoiler alert: pretty much. The actual caper is well laid out, with a lot of sleuthing and surveillance, a few moments of swift action, a suspicious Kiwi cop, a love/hate dynamic between Kent and Compton, and precise local color in both Hong Kong and Auckland.

We consider The Blue Pheasant to have been a worthwhile purchase. That was actually almost a given, considering the low price for the book (Seven dollars? Sold!). But our point is that you never know what you'll get with a writer as obscure as Boswell. Well, now we do. And we have his sequel, 1959's Lost Girl. We'll get around to reading that later.

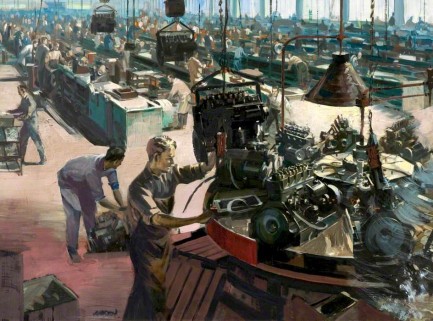

Turning back to the cover for a moment, the example at top is one we downloaded from an auction site because the William Collins Sons & Co. edition, which is a hardback with a dust jacket, shows the wonderful art painted by British talent John Rose to best advantage. The edition we actually bought is a paperback from Fontana Books, and our scans of that appear below. They're fine, but the cleaner Collins version is frameworthy. We have another Rose cover at this link, and we'll be getting back to him again shortly.

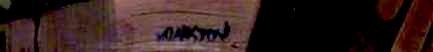

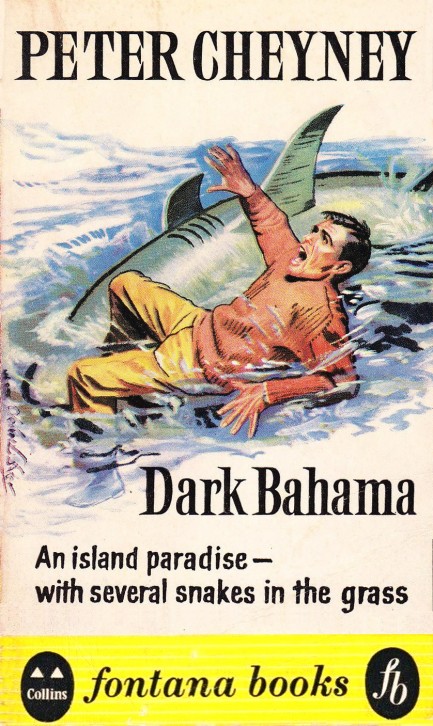

Turns out sharks like the catch of the day too.

As soon as we saw this cover for Peter Cheyney's 1950 novel Dark Bahama we had to read the book. We had to find out if this was a literal illustration. And yep, a guy gets eaten by a shark. The artist here, John L. Baker, painting this for Fontana's 1960 edition, must have really enjoyed creating something different from the usual gun toting studs and chain smoking femmes fatales. The story is different too. In a tale set on the fictional Bahamian island of Dark Bahama, Cheyney creates an array of Afro-Bahamian characters, filling roles from fishermen to police officials, and, surprisingly, writes them with something nearing respect. The addition of a mysterious Belgian character makes for another fun spot of diversity.

The protagonist is Julian Isles, a British detective hired to locate a globetrotting ingenue and rescue her from Dark Bahama before her partying and dubious associations permanently embarrass her family. Isles immediately walks into a murder scene, is suspected by the local cops, begins to think his client has lied to him, and sets about defying orders and expectations to get to the bottom of it all. Getting to the bottom involves working with the aforementioned Belgian cipher, Ernest Guelvada, a tough, romantic, eloquent, and ruthless operative of vague provenance. We think he's one of the best characters we've come across in mid-century literature. Just listen to this guy:

“I am delighted to meet you. I am more than delighted to bring a little excitement into your—what is the word—prosaic existence. Yes, goddam it, you will agree with me that there is nothing like a couple of murders to stir the blood of a police commissioner at three-thirty in the morning.”

And:

“You think so? You lie. More than that, my friend, you love her. That I know. When you speak of her I see the look in your eye. I have discovered your secret. I will tell you something else. I also love her. I, Guelvada, who loves every woman in the world, love her at least as much as the other few million.”

And:

“When I go into action, my friend, I like a lot of room and a lot of space. Like great armies I must have room to develop. Like great fleets I must have space to maneuver. You understand? It is for this reason that I do not wish this island to be cluttered up with non-essential women, and at the moment our beautiful Miss Lyon is non-essential. Therefore, she will stay in Miami.”

To us, that sounds like a writer having a very good time with an off-the-wall character. Guelvada's reasons for turning up change Dark Bahama from a mystery to an espionage tale, but we won't reveal the details. We suggest reading it yourself. Cheyney is famous for his Lemmy Caution series, which began back in 1935, but we think he's better here fifteen years later—a better stylist and a better conceptualizer, who's produced a generally better read than we think he was capable of back when he started out. The story is engaging, the femme fatale is fascinating, the secondary characters ring true, the bizarre Ernest Guelvada keeps reader interest high, and the island backdrop adds atmosphere and spice. With Dark Bahama Cheyney gave us more than our money's worth.

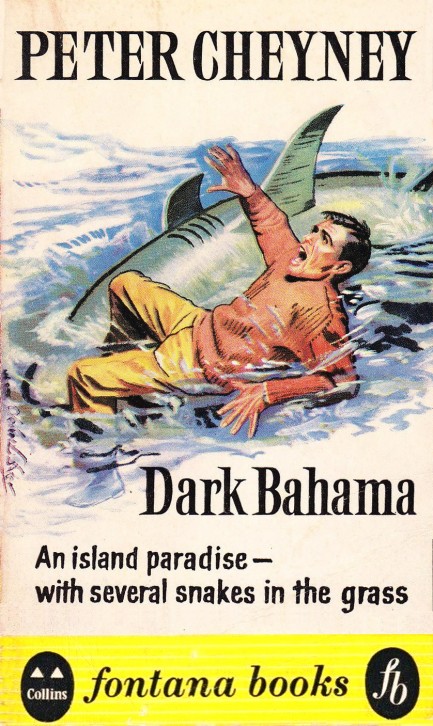

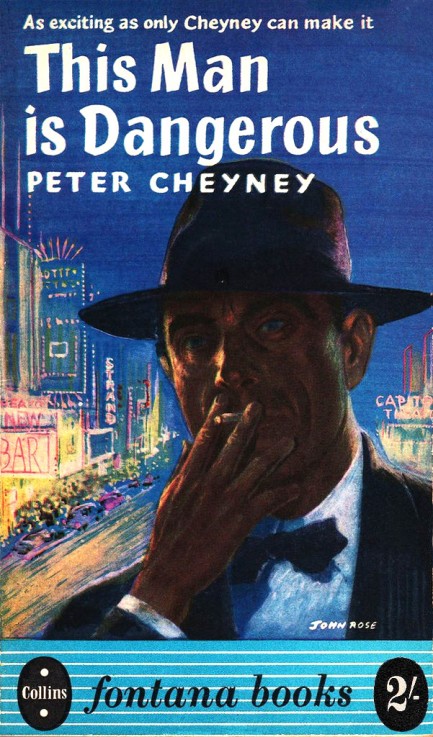

Lemmy put it to you as directly as possible.

Peter Cheyney debuted as a novelist in 1936 with the Lemmy Caution novel This Man Is Dangerous, and true to the title, his franchise character is one bad mutha-shut-your-mouth. We like the scene where he leg locks a guy around the neck, then proceeds to lecture him for two pages about how he's going to kill him and enjoy it, before actually breaking his neck. The crux of the story involves a plot to kidnap an heiress in London. Cheyney details Caution's wanderings around the dark recesses of the Brit underworld and slings the slang like few writers from the period. Much of it is amusing, though he never quite makes it to the level of “moo juice.” But here's the thing about loads of slang in vintage literature—it can wear on you after a while. And when paired with a storyline that doesn't exactly sprint like Usain Bolt, it can really wear on you. You have to give Cheyney credit, though. He was unique. And successful. This Man Is Dangerous was adapted to the screen as the French film Cet homme est dangereux in 1956, and numerous other novels of his made it to the moviehouse as well. We weren't thrilled with this tale, but it's significant in the crime genre, and objectively we think many readers will love it. The Fontana edition you see above has amazing cover art by John Rose and was published in 1954.

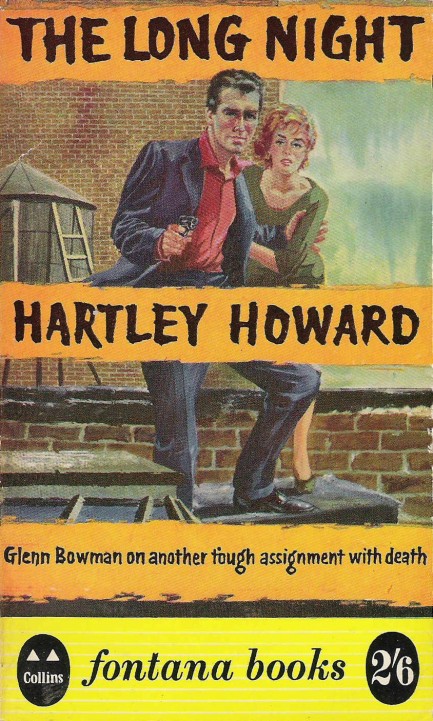

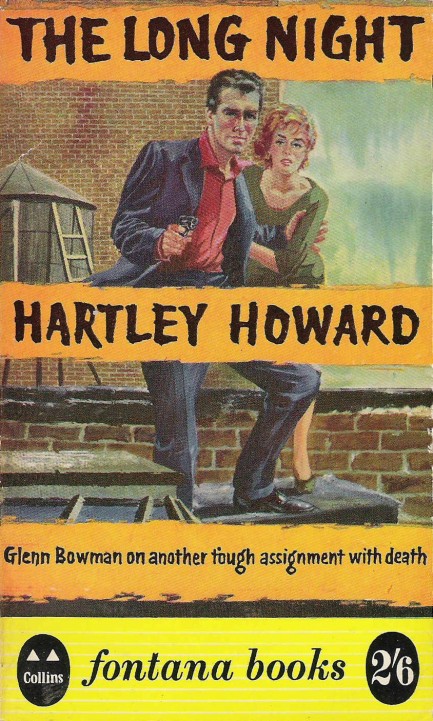

Wow, that night sucked. And considering we have to jump to the next rooftop, today's not looking so good either.

Every author of detective novels must wrestle with the problem of how to bring the hero into the case. Hartley Howard takes a unique route in 1959's The Long Night—a seeming crank call. A woman rings private dick Glenn Bowman in the middle of the night, drunk, despondent, and hinting at suicide. She sounds sexy as hell, so Bowman coaxes her address from her and speeds over there to prevent tragedy—and get a gander at this honey-voiced, late night phone phantom. The only problem is she isn't planning to commit suicide, and the call was never random in the first place.

From there the mystery takes on a familiar shape, as Bowman must solve a murder in order to stay out of hot water with cops who want to pin the crime on him. Despite the book's title, the tale spans multiple nights. Overall it's okay but it's hard to buy a guy constantly talking people out of killing him. Especially when he's such a pest. Like James Bond, none of the bad guys can seem to take the expedient route of just ventilating Bowman. At times this will leave you scratching your head, but Howard has the hard boiled lingo pretty well mastered, we'll give him that. Some prime examples:

Femme fatale in response to hero's flirtations: “You got lots of crust, mister, but not enough pie.”

Hero after fighting a broken armed thug: For a guy with a busted fin he didn't make out so bad.

Hero wondering if a woman is going to shoot him: Deep in her eyes lay an enigma that only the gun could answer.

Hero in a car with distrustful femme fatale: We drove uptown like two people whose marriage had outlived its romance.

You get the picture. We'd never heard of Hartley Howard before, but we looked him up and learned that he was really Leopold Horace Ognall. Born in Canada but based in Britain, Ognall was not as obscure as we'd assumed. The Long Night was number thirteen in a series of thirty-eight Glenn Bowman novels he published between 1950 and 1979, and he also wrote forty novels under the name Harry Carmichel. Which just goes to show that there's always another major writer to discover. That's why this pulp gig never gets old.

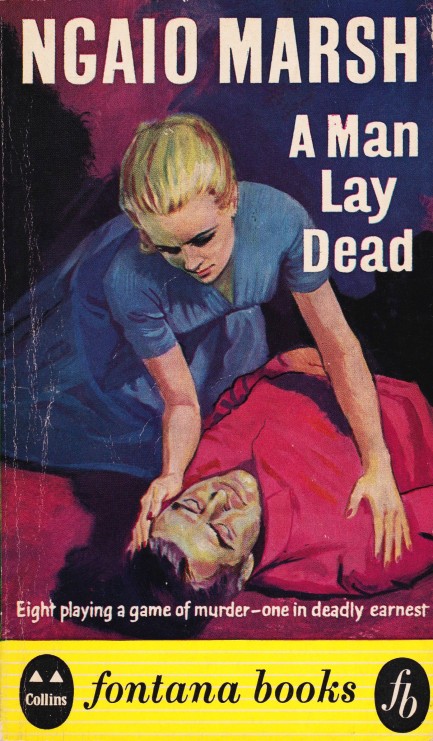

Are you sure he's been murdered? Sometimes he's just too damned lazy to move.

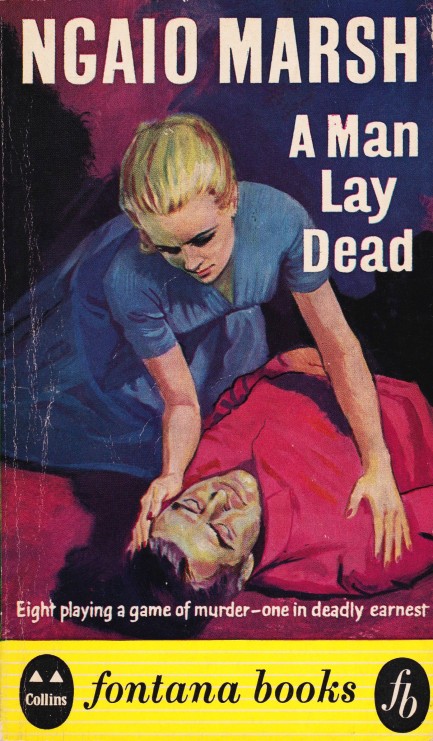

Above, a cover for A Man Lay Dead, written by New Zealand born author Ngaio Marsh, a heavyweight in whodunnits, which is exactly what this book is. A house full of people, a harmless game of murder mystery where a person somehow ends up actually stabbed to death with a priceless dagger, and sleuth Roderick Alleyn called upon to solve the crime. We're not big fans of these types of books, but they can be interesting, and this one manages to achieve that, though it drags toward the end. 1934 originally, with this Fontana edition appearing in 1960.

|

|

The headlines that mattered yesteryear.

2003—Hope Dies

Film legend Bob Hope dies of pneumonia two months after celebrating his 100th birthday. 1945—Churchill Given the Sack

In spite of admiring Winston Churchill as a great wartime leader, Britons elect

Clement Attlee the nation's new prime minister in a sweeping victory for the Labour Party over the Conservatives. 1952—Evita Peron Dies

Eva Duarte de Peron, aka Evita, wife of the president of the Argentine Republic, dies from cancer at age 33. Evita had brought the working classes into a position of political power never witnessed before, but was hated by the nation's powerful military class. She is lain to rest in Milan, Italy in a secret grave under a nun's name, but is eventually returned to Argentina for reburial beside her husband in 1974. 1943—Mussolini Calls It Quits

Italian dictator Benito Mussolini steps down as head of the armed forces and the government. It soon becomes clear that Il Duce did not relinquish power voluntarily, but was forced to resign after former Fascist colleagues turned against him. He is later installed by Germany as leader of the Italian Social Republic in the north of the country, but is killed by partisans in 1945.

|

|

|

It's easy. We have an uploader that makes it a snap. Use it to submit your art, text, header, and subhead. Your post can be funny, serious, or anything in between, as long as it's vintage pulp. You'll get a byline and experience the fleeting pride of free authorship. We'll edit your post for typos, but the rest is up to you. Click here to give us your best shot.

|

|