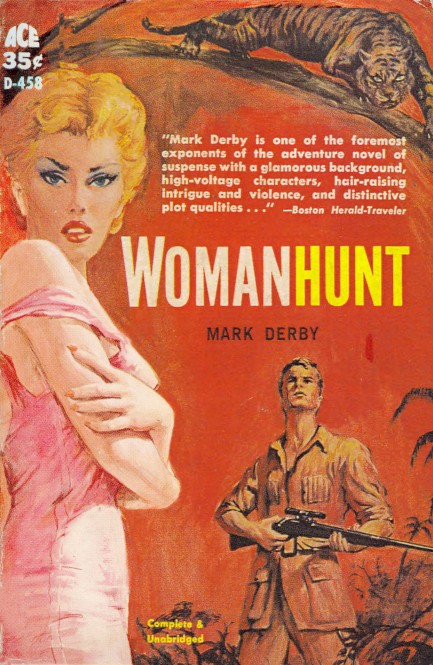

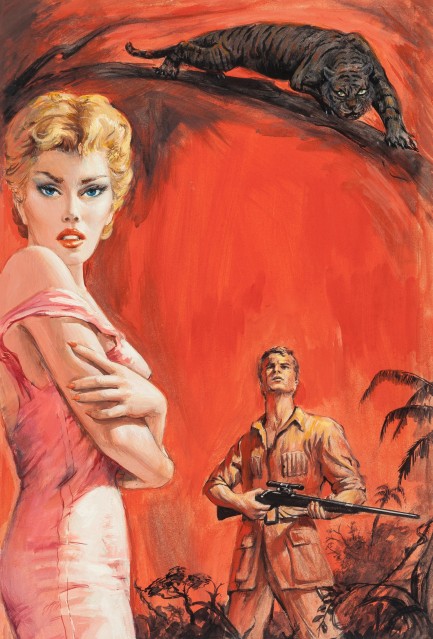

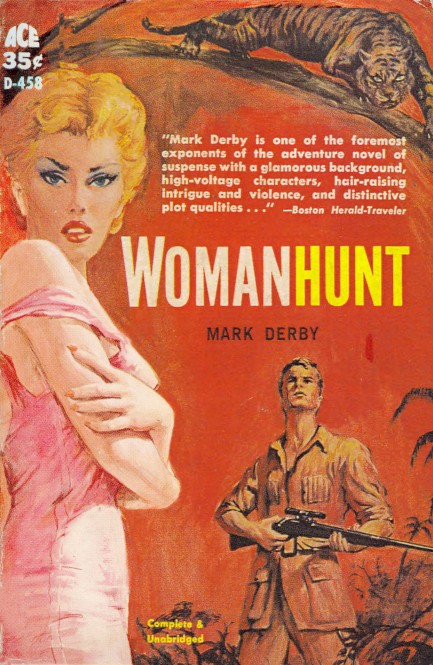

He's hopelessly outclassed by his prey. And the tiger is a problem too.

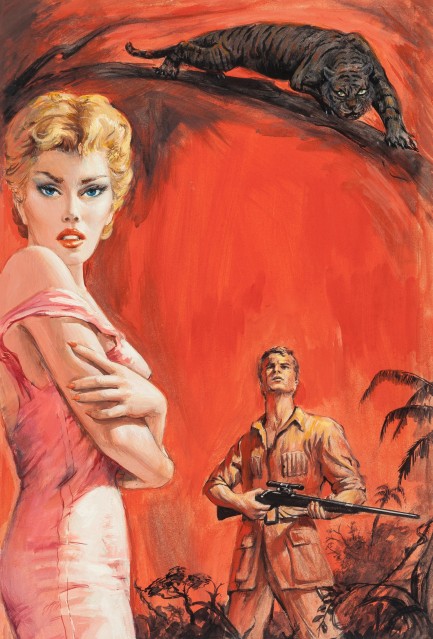

Above you see a nice cover by an uncredited illustrator for 1959's Womanhunt, written by Harry Wilcox posing as his alter ego Mark Derby and published in this Ace paperback edition in 1960. This is interesting visual work. You notice that the femme fatale's eyes resemble the tiger's eyes. That comparison is at the crux of the tale Derby tells. In the story a government agent named Dickson (Dix to his friends) is sent upcountry in Malaya to pose as a big game hunter there to kill a deadly tigress, while behind the scenes he's searching out a communist cabal and determining whether an agent already there is doing her job or has turned.

That agent—Anna Swansey—is someone Dix barely knows but is “miserably and hopelessly in love with.” Under the pressure of his mission, his feelings turn into a consuming obsession. As high concept novels go, the idea of trying to stalk an apex predator, arouse love within a woman, and expose a spy ring all at once is as ripe as it gets. There's a lot going on at all times, and Derby keeps multiple plates spinning on sticks while treating readers to some nice passages, like this one:

Before her magnificent body, an electric apparition of charcoal, gold, and white, had passed out of sight, he had a second view of her snarl, the haughty sneer that drew mouth and white whiskers high and quivering on each side, the narrowing of the usually rounded eyes, the flash of the ivory teeth.

At one point Dix is alone in the jungle and hears the tigress's roar. It's a moment when he realizes, terrifyingly, that his hunt of her may have turned into her hunt of him:

He jumped as if a cannon had gone off. He had got it into his head that she was somewhere over on his right, or behind him, and this growl came from directly ahead. It sounded awesomely near, too. [snip] The roar, a sound which perhaps only one in every million human beings ever hears, and only one in ten million ever hears at close quarters, filled the dark jungle with shock. There was a moment, perhaps of one second, during which Dix did nothing but stiffen; then his arms moved and the beam of the flashlight mounted on the rifle barrel cut a cone of light in the dark clearing.

The title of book registers weird in 2024, but it isn't misogynist—or not very. A few web pages say the woman of the hunt is, metaphorically, the tigress. No. It's a metaphor, alright, but not one that simple. The woman of the hunt is actually both the tigress and Anna. That's made clear because Derby flogs the woman-as-tigress metaphor until it's welted from nose to tail. But he's also capable of smirking at it, briefly anyway, such as here:

“My grandfather used to say that a tigress was a woman, a woman who did not wish to be caught. She would hide down trails the hunter didn’t know and, just like a woman, her lies would be more clever than his traps. That’s what he used to say.” ’Che Kadan was fond of quoting his grandfather, who’d been one of the Malayan sultans—an old man of character, it seemed, since his quoted remarks were invariably mere clichés or sentimental platitudes which must have been remembered for the authority with which he’d uttered them.

It's a comparison that's probably insulting to most modern women, but don't let it fool you. The tale is steeped in debilitating male emotion, lustful obsession, existential terror, and a desperate loneliness. It reads tragically at times, as Dix tries but fails to keep Anna from slowly taking over his thoughts. And that's another unusual aspect of the book: Dix is increasingly driven by jealousy. At first it's directed only against Anna's boss Charlton Lang, who also wants her badly and uses his authority to constantly keep her near him in a work capacity. Then Anna's ex-lover shows up. Dix is driven near to madness by this event.

Derby deals in high emotion. For example, big cats generally kill humans when they're the only obtainable prey. Usually the animal is hurt, or very old. Dix sympathizes with the tigress, doesn't consider her to be in any way at fault, but people keep getting eaten, so he has no choice about killing her—not merely as matter of his cover, but as a matter of saving lives. His conflict over this is wrenching, symbolic of terrible choices forced on us all. To add an extra ingredient, he isn't an experienced hunter. He can shoot—but he isn't expert. His pursuit of the tigress is ridiculously dangerous.

This is a great book. However, the usual warnings apply to colonial fiction. In addition, within the communist plotlines Dix's quarries are all fools, monsters, or victims of coercion. Capitalism wasn't then—and isn't now—turning the world into a fruit laden banquet table overflowing with goodness for all, and Derby was surely smart enough to understand that. But despite the billions killed to establish and maintain his preferred global order, he never touches the reasons why alternative political philosophies take hold. In his mind, resistance comes from the deluded, from dolts who—for inexplicable reasons—believe colonials have no right to steal foreign lands. That may annoy the more politically objective readers.

But while more character depth on that front would have made Womanhunt perfect, and its total and rather smug one-sidedness means it has to be partly classified as propaganda, Derby can really construct and deliver an adventure. How do you wrap up a communist spy caper, Malayan big game hunt, and heart-hurting love story all at once? Those spinning plates never wobble. The hunt's spectacular end flows immediately into the climax of the spy tale, and within that chaotic resolution the love story concludes with fireworks. We'll be revisiting Derby soon.

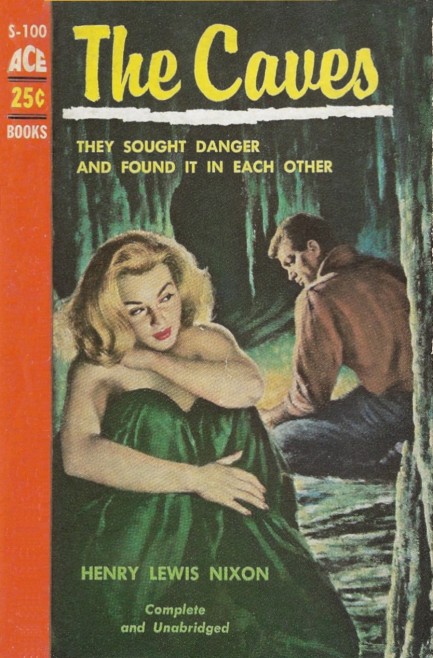

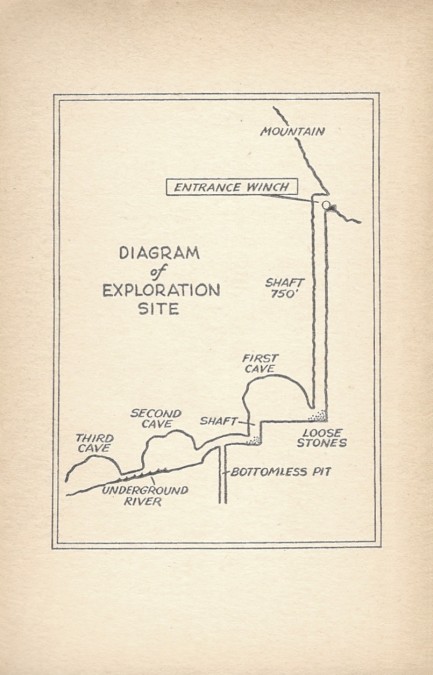

What is it about being deep inside the dark, damp earth that makes me incredibly horny?

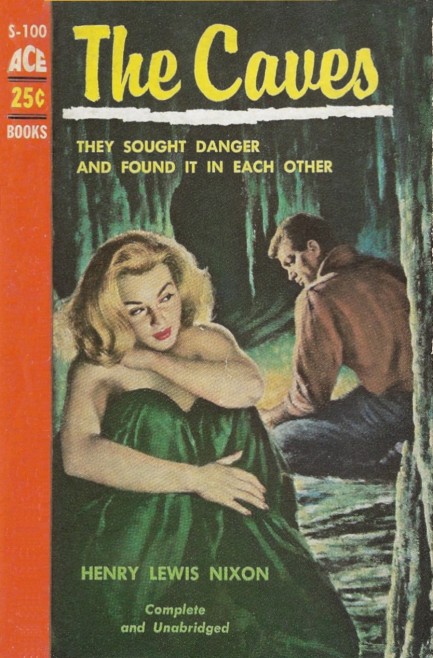

We bought Henry Lewis Nixon's 1955 novel The Caves—for which you see an Ace Books cover above with uncredited art—based upon the rear teaser blurb. It told us that the tale was about a group of people who face deadly problems after becoming trapped in an underground cavern system. That struck as unusually high concept for the 1950s, so we took the plunge. The book wastes no time, opening with the group in mid-descent. Trouble strikes immediately, then again, then again, ad infinitum. There's hypothermia, epilepsy, a broken foot, a bottomless pit, and other obstacles. Nixon doesn't let up, and for that he deserves credit. But while the story is interesting and propulsive, there's one major flaw—it's written at a level that feels young reader.

That isn't inherently bad. The Hobbit is written at young reader level, and it's great. But Nixon didn't mean for The Caves to be that way. There are many adult concepts—sexual predation and PTSD among them—but his characters are so cardboard, their ruminations so shallow, their motivations so transparent, that there's no way for them to resonate for adult readers. At least as far as we're concerned. One character loves sex, for example. It would take a very good writer to make her obsession with getting laid—in a freezing cavern and to the detriment of her own safety—anything other than sophomoric. Even the multiple womb metaphors don't make the book less like youth material. It's ironic, but Nixon's story about a fraught subterranean exploration needed to be deeper.

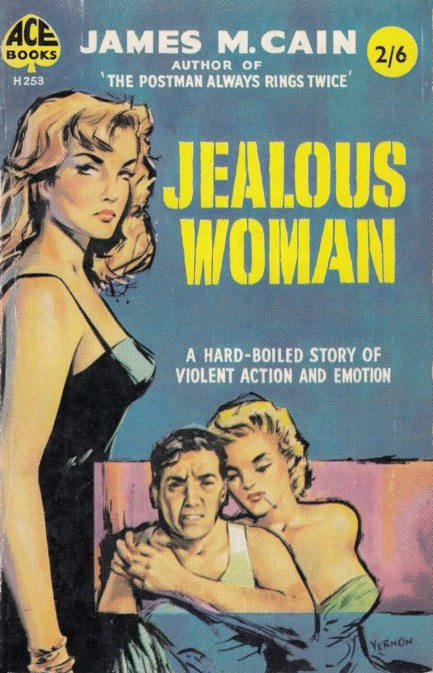

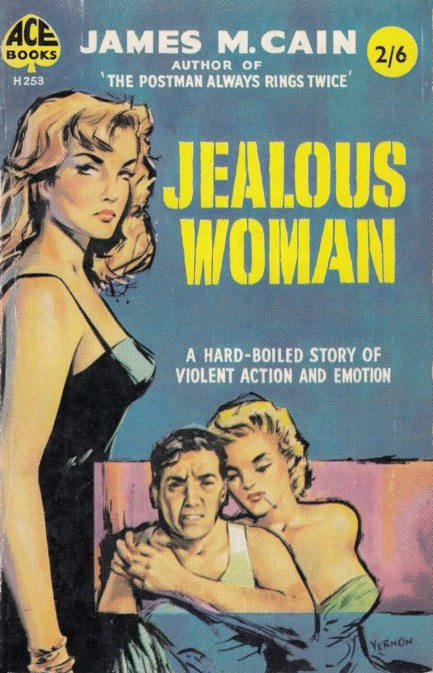

There's no jealousy like a femme fatale's jealousy.

It's amazing how much easier James M. Cain makes writing seem than scores of other authors. His 1950 novel Jealous Woman starts at a gallop. Here's the first line: At the desk, when they said she was in 819, I knew hubby or pappy or somebody was doing all right by their Jane, because 19 is the deluxe tier at the Washoe-Truckee, one of our best hotels here in Reno, and you don’t get space there for buttons. And just like that we're off. Cain gives readers ambitious insurance man Ed Horner of General Pan-Pacific Insurance of California. Horner lives, works, and parties in Reno, where unhappy marrieds migrate to be freed from their nuptial bonds. He gets involved in a complex divorce/annulment scheme between Jane Delavan, her rich husband, Jane's ex-husband, and his current wife. Yes, it's a bit complicated, but a messy murder uncomplicates it a little. At least for readers. For Horner, things get weird. Jealous Woman isn't Cain's best, but it's still a slice of devious fun worth reading, and this Ace version with John Vernon cover art is the edition to buy if you can.

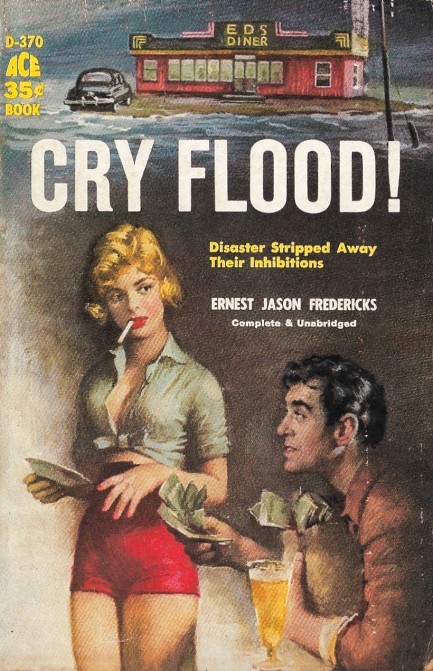

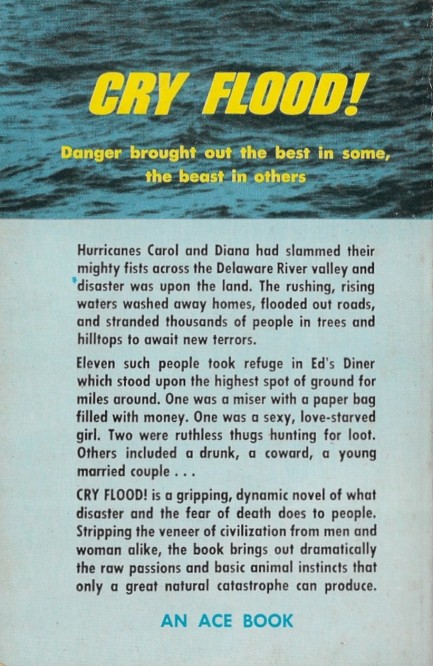

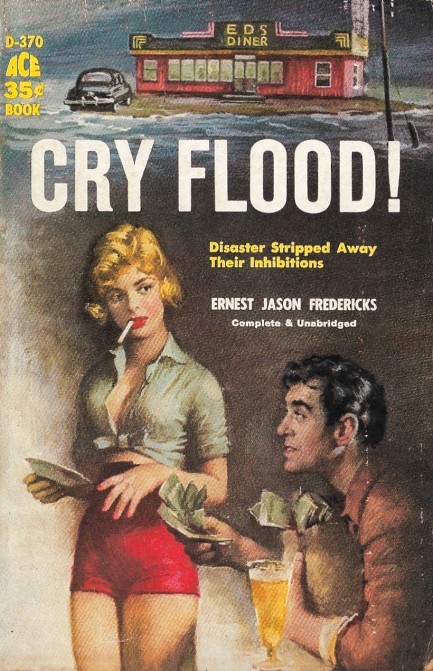

1959 flood thriller proves that even during a natural disaster money, booze, and women are all that matter.

Ernest Jason Fredericks', aka Paul Ernst's 1959 novel Cry Flood!, for which see an Ace paperback edition above with nice art by George Ziel, is a thriller in the flood/hurricane sub-genre on which we've gotten hooked in recent years. We've read entires from John D. MacDonald, Theodore Pratt, Malcolm Douglas, and others. It seems as though the close quarters and ticking clock aspects built into disaster settings bring out the best in authors.

In Cry Flood! Fredericks sets the action in a New Jersey diner perched on high land as two hurricanes to the south and unseasonable rain in the region bring the nearby river to the record crest of a 1936 flood—then beyond. Converging on the diner are a bank-phobic miser carrying twenty-six thousand dollars, four married couples, and two criminals who catch wind of the money and intend to steal it. The problem is the flood waters rise too high for anyone to leave, which means the crooks must bide their time, prompting them to spend it terrorizing those with whom they're trapped.

In Fredericks' hands, the two bad men are synonymous with the flood, implacable and unavoidable, forcing the couples to face their fears and admit their failings before death sweeps them away. Or not—but only if they're brave and lucky. It was quite well done, and consistently enjoyable. For our money, the best of the flood/hurricane lot so far has been John and Ward Hawkins' A Girl, a River, and a Man, but Cry Flood! held its own in what has continued to be fertile pop fiction territory.

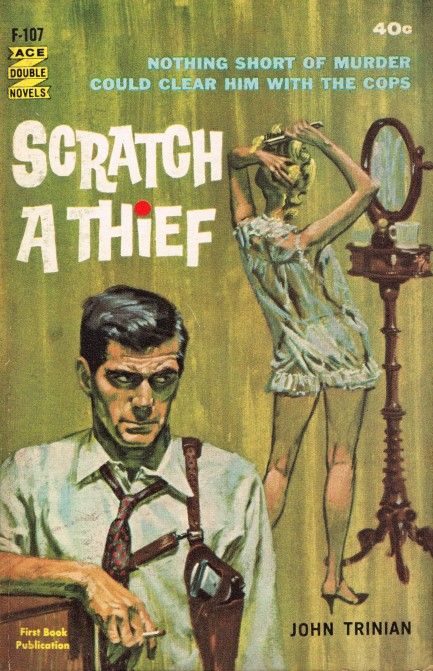

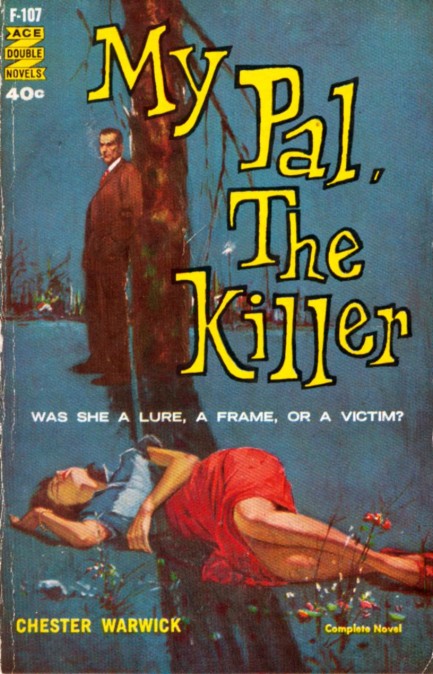

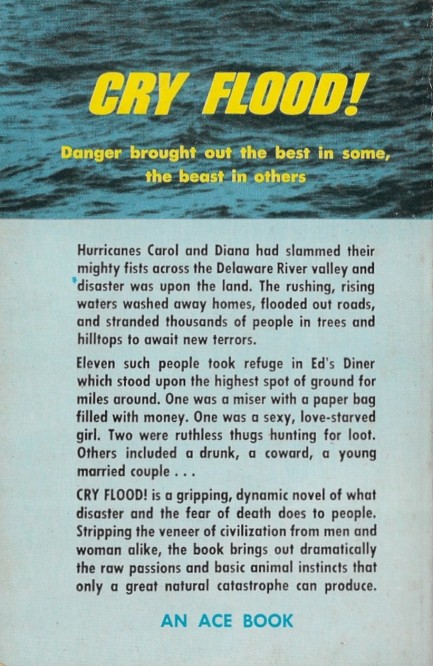

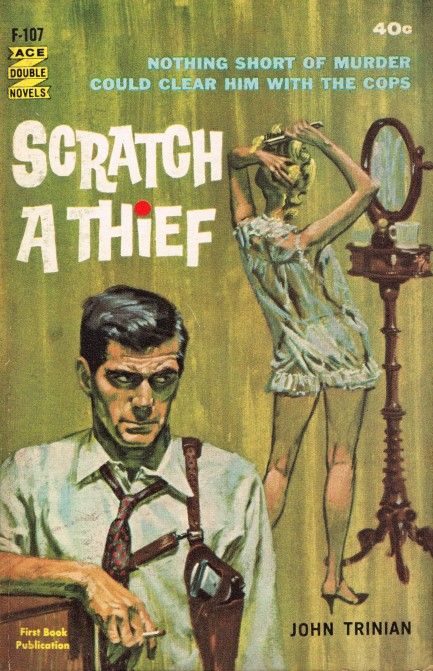

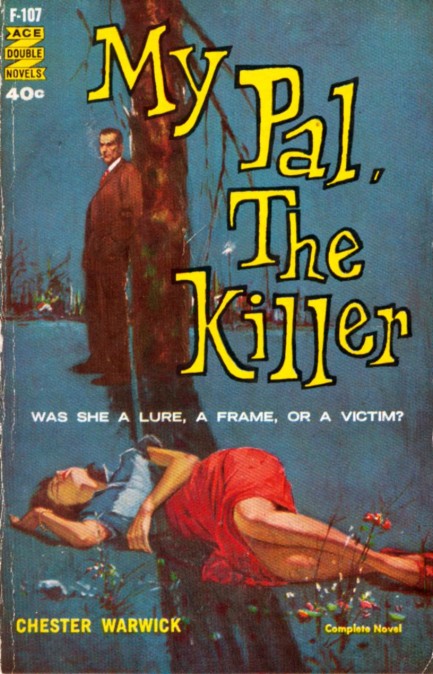

Not to complain, oh great master thief, but all you've stolen lately has been booze money out of my purse.

The thieving business runs hot and cold, and it reaches freezing depths when your girlfriend starts giving you a hard time about your earnings. Actually, let's not restrict that to thieving. It's true whatever your chosen field happens to be. John Trinian's Scratch a Thief was published in 1961 as an Ace Double Novel with Chester Warwick's My Pal, The Killer. Scratch a Thief later became a movie with Alain Delon and Ann-Margret in the leads, and at that time was retitled Once a Thief and credited to Trinian's pseudonym Zekail Marko. In reality, he was neither Trinian nor Marko, but Marvin Schmoker. So, you can understand the name changes. High school must have been hell for the guy. We haven't read him yet but we'll get around to it. And maybe to Chester Warwick too. You never know. But we'll for sure get around to the movie.

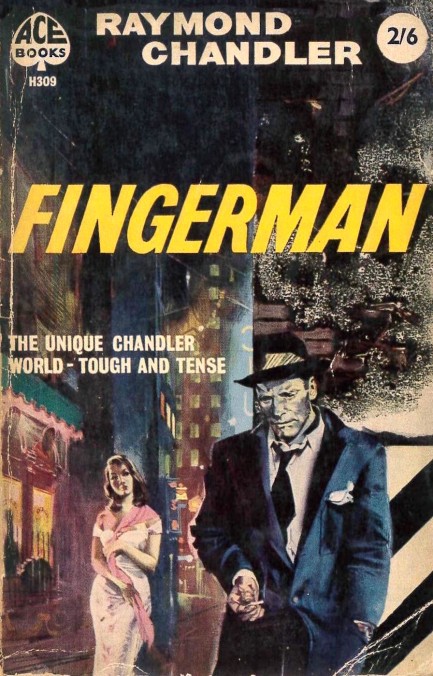

*sigh* That was really unpleasant. I don't know why, but I always assumed it was just a euphemism.

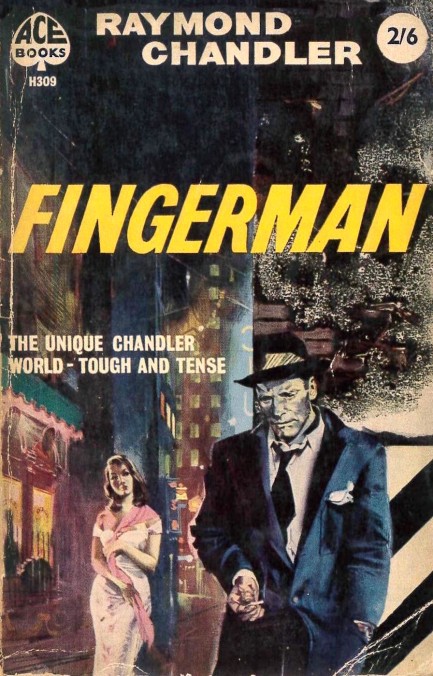

This cover for Raymond Chandler's 1960 story collection Fingerman was painted by an uncredited artist, but once again we're thinking it's Sandro Symeoni on the brush. 1958 to 1960 was when he was working extensively with Ace Books, and this illustration is very much in his style, as we've discussed here and here. The book consists of four offerings: the stories “Finger Man,” which was first published in Black Mask in October 1934, “The King in Yellow,” from the March 1938 issue of Dime Detective Magazine, and “Pearls Are a Nuisance,” also from Dime Detective Magazine, coming in April 1939. The last piece is a Chandler essay titled, “The Simple Art of Murder.” A couple of the aforementioned tales also appeared in Five Sinister Characters. All the stories are good, but we talked about “The King in Yellow” in a bit more detail a while back, so if you're interested feel free to check here.

At least we're still in love after all these years, honey. You're in love with a waitress, and I'm in love with a cabana boy.

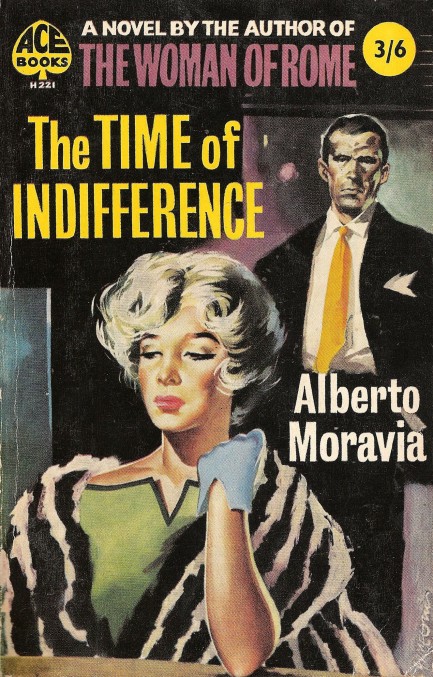

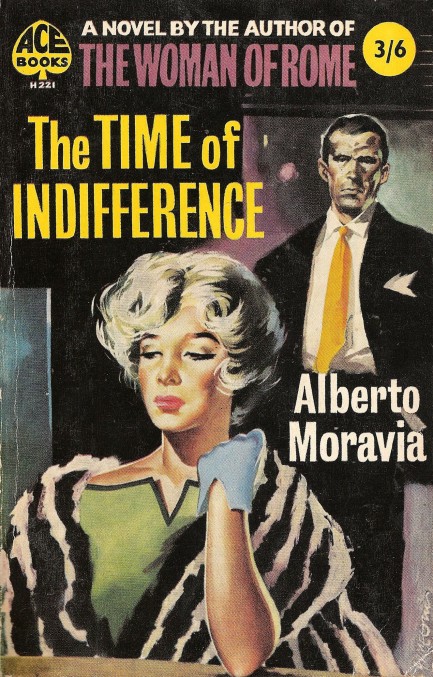

We're back to Italian illustrator Sandro Syemoni today, who we consider a genius in his field. Above you see his cover for Ace Books' 1958 edition of Alberto Moravia's The Time of Indifference, which was originally published in 1929 as Gli indifferenti. We gather it was quite a racy book and it sold out in weeks. Ace, as we've mentioned before, repackaged a lot of literary fiction with newly provocative covers. If you're going to go that route, Symeoni was close to the best. See what we mean here and here. And check some of his poster work here.

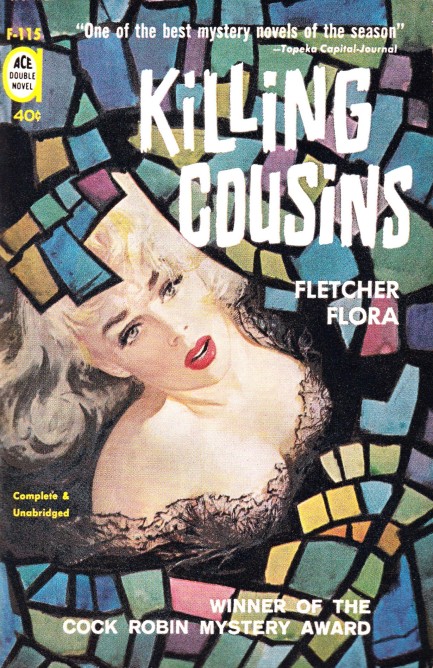

If you can't count on on family, who can you count on?

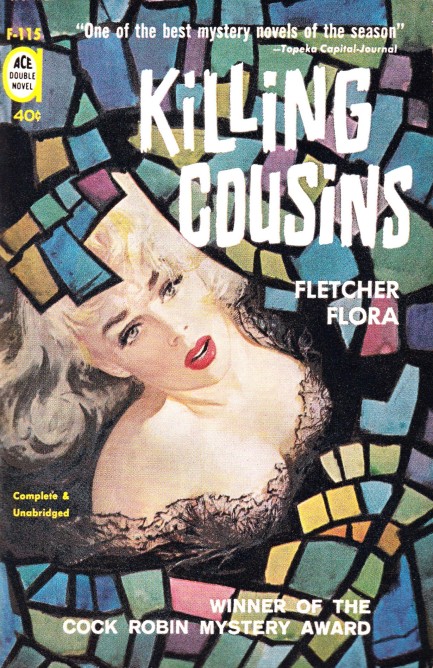

For a few years we've been meaning to get back to Fletcher Flora, and finally we've done it. Above you see his half of an Ace Double novel—Killing Cousins. The book is about a spoiled suburban wife who shoots her husband, then calls on one of her lovers—her husband's cousin—for help in covering up the crime. Cousin Quincy is known to be a genius, and he relishes the challenge of outwitting the cops. Generally, he does fine. It's the people around him he can't count on, including his cousin Fred, who, because he doesn't know about the murders and thus doesn't realize the importance of what he's asked to do, botches his crucial task. It's only the first of many problems. Flora has a unique voice, no doubt about it. Some might find it too self-conscious, but we liked it. Check out the two examples below:

When she had first wakened and remembered what had happened, she had been very frightened and had felt a necessity to do something immediately, no matter what, but then it had occurred to her that it all might be nothing more than a bad dream, which she sometimes had, and so she had gone into Howard’s bedroom to make sure, one way or the other, and it had turned out not to be a dream at all, for there Howard was on the floor.

Heretofore, cousin Fred’s approach to women had been direct and simple, even somewhat primitive, and if the approach was no more than moderately effective on the whole, it had at least left him unfettered and uncluttered, free alike of uncomfortable commitments and emotional hangovers. If a chick would, she would. If a chick wouldn’t, she wouldn’t. And if she wouldn’t, to hell with her. That, in brief, was cousin Fred’s position.

Flora's writing feels like it comes from someone who knows exactly what he's trying for and absolutely achieves it. There are no missteps. Plotwise, the murderous wife, apart from shooting her husband, is mostly a bystander. The success or failure of the cover-up rests entirely in cousin Quincy's hands, and he's confident to a fault. As holes develop in his clever plot, he's forced to improvise, and ultimately Flora boils the drama down to how fast Quincy can think, and whether the police are competent investigators. Speaking of which, we'll give Flora credit for one of the great cop names of all time—Elgin Necessary. We think Killing Cousins is a necessary read based on its unusual style alone.

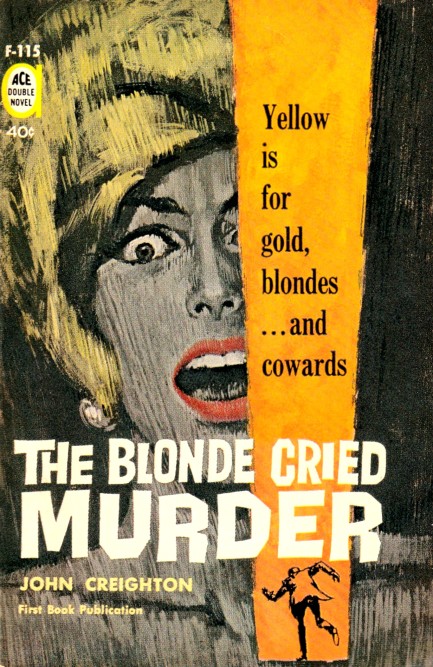

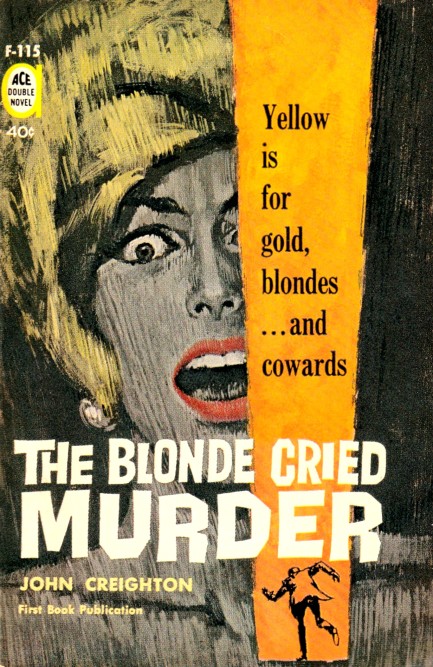

By comparison, John Crieghton's, aka Joseph L. Chadwick's, The Blonde Cried Murder is much more what you'd expect from a mid-century crime novel. The set-up sounds like the beginning of a joke: a woman walks into a detective's office. We like books that start that way. We think of such authors the way we think of musicians who decide to cover a classic. It's been done before, but not in that exact style. So, a woman walks into downtrodden private dick Ed Donovan's office and asks him to find a missing person—her husband, who may have fled to avoid the police. of such authors the way we think of musicians who decide to cover a classic. It's been done before, but not in that exact style. So, a woman walks into downtrodden private dick Ed Donovan's office and asks him to find a missing person—her husband, who may have fled to avoid the police.

From there the tale continues in classic directions: Donovan drinks way too much, he's soon on the hook for a murder he didn't commit, there's money that needs to be found, etc. And of course, romance rears its inconvenient head. The book is an unusual flipside to Killing Cousins because of how standard it is by comparison, but it's worth a read. Not that you have a choice. To read one means to buy both. Some Ace doubles can cost a lot online, but this one is usually reasonable. There are two copyrights, 1960 for Flora and 1961 for Creighton, and the cover art for both is uncredited.

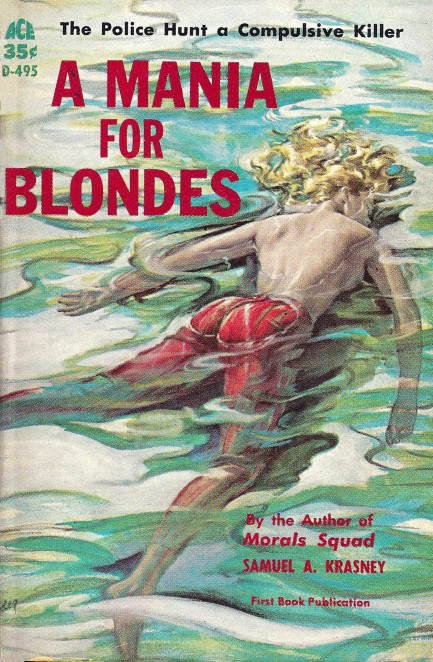

Whatever floats your corpse.

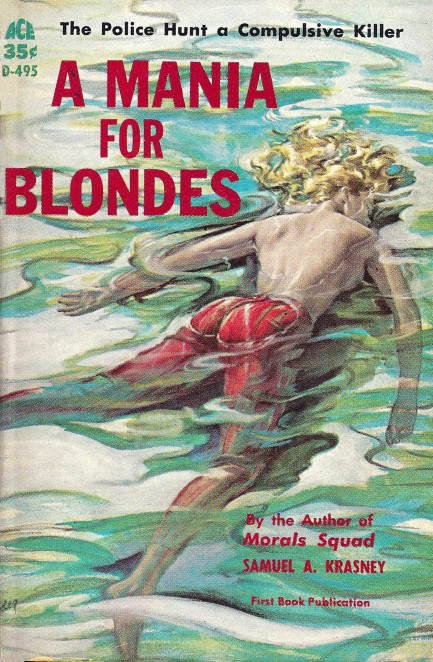

Art by Paul Rader fronts this copy of Samuel A. Krasney's A Mania for Blondes, a police proceedural dealing with two women drowned in Philadelphia's Delaware River, and the investigation to bring a killer to justice. The protagonist here is vice detective Ben Krahmer, who learns that both victims appeared in nudie reels. The clues lead down the rabbit hole of illicit porn and toward a mysterious suspect witnesses think looks like Zorro—but who Krahmer soon realizes may be a member of Pennsylvania's traditionally garbed Dutch community. Procedurals sometimes—as is the case here—fail to provide deep characterizations, but the mechanics of the investigation are interesting. Krasney constantly refers to his protagonist as “the Morals man”—capital M—which we found weird, but we thought this outing was solid overall and we liked the Zorro imagery. Even so, we probably won't go looking for more from Krasney unless we run across him cheap. There are, after all, so many paperbacks, and so little time.

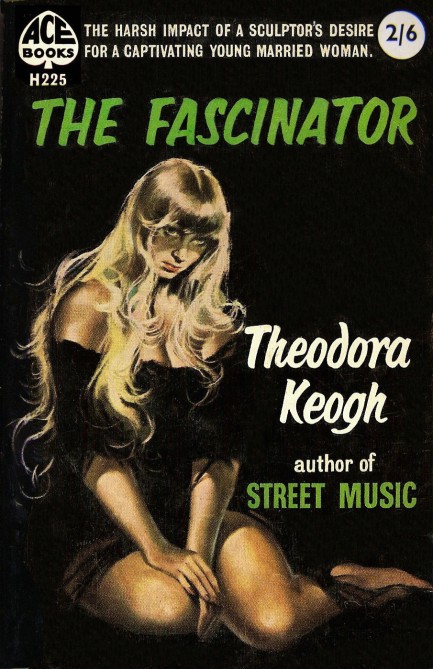

Beauty is easy to love. Ugly takes unresolved psychological issues.

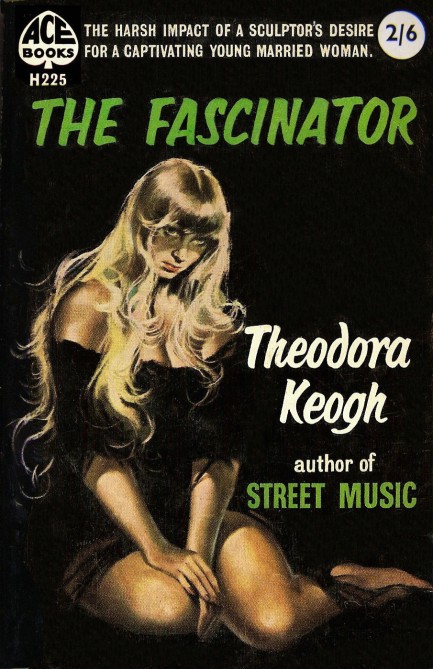

Spouses who cheat usually don't do so because their fling is more attractive than their partner. We learned this years ago from a widely noted survey of cheaters. What attracts them is that the person they desire is more exciting. Theodora Keogh's 1954 novel The Fascinator encapsulates this idea. It's about a woman's attraction to a man who's more exciting than her husband. The other man, Zanic, is ugly due to a congenital condition that made his brows and ears grow so he looks like an ape, and he's also overweight. But no matter—he's a sculptor and an elegant speaker and all the rest, so the story, as it develops, follows whether the main character Ellen will actually cheat with this persistent and somewhat creepy ogre of a man who she finds more exciting than her handsome but normal husband. It's not the type of book we usually read, but blame the cover art for that. It drew us because we thought it might be another Sandro Symeoni effort for Ace Books. It's uncredited, but we suspect Sandro's brush. Why? Look here. In any case The Fascinator is well written and thoughtful.

|

|

The headlines that mattered yesteryear.

2003—Hope Dies

Film legend Bob Hope dies of pneumonia two months after celebrating his 100th birthday. 1945—Churchill Given the Sack

In spite of admiring Winston Churchill as a great wartime leader, Britons elect

Clement Attlee the nation's new prime minister in a sweeping victory for the Labour Party over the Conservatives. 1952—Evita Peron Dies

Eva Duarte de Peron, aka Evita, wife of the president of the Argentine Republic, dies from cancer at age 33. Evita had brought the working classes into a position of political power never witnessed before, but was hated by the nation's powerful military class. She is lain to rest in Milan, Italy in a secret grave under a nun's name, but is eventually returned to Argentina for reburial beside her husband in 1974. 1943—Mussolini Calls It Quits

Italian dictator Benito Mussolini steps down as head of the armed forces and the government. It soon becomes clear that Il Duce did not relinquish power voluntarily, but was forced to resign after former Fascist colleagues turned against him. He is later installed by Germany as leader of the Italian Social Republic in the north of the country, but is killed by partisans in 1945.

|

|

|

It's easy. We have an uploader that makes it a snap. Use it to submit your art, text, header, and subhead. Your post can be funny, serious, or anything in between, as long as it's vintage pulp. You'll get a byline and experience the fleeting pride of free authorship. We'll edit your post for typos, but the rest is up to you. Click here to give us your best shot.

|

|

of such authors the way we think of musicians who decide to cover a classic. It's been done before, but not in that exact style. So, a woman walks into downtrodden private dick Ed Donovan's office and asks him to find a missing person—her husband, who may have fled to avoid the police.

of such authors the way we think of musicians who decide to cover a classic. It's been done before, but not in that exact style. So, a woman walks into downtrodden private dick Ed Donovan's office and asks him to find a missing person—her husband, who may have fled to avoid the police.