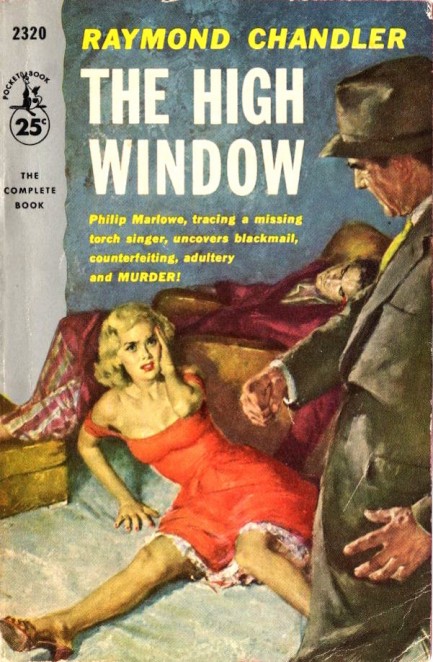

It's a beautiful Window even if it doesn't illuminate the identity of the cover artist.

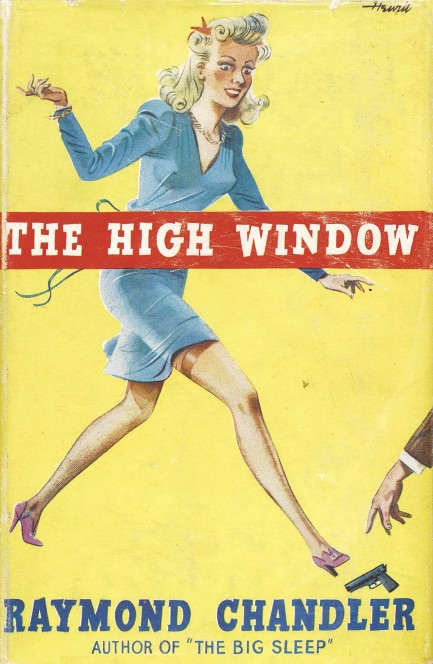

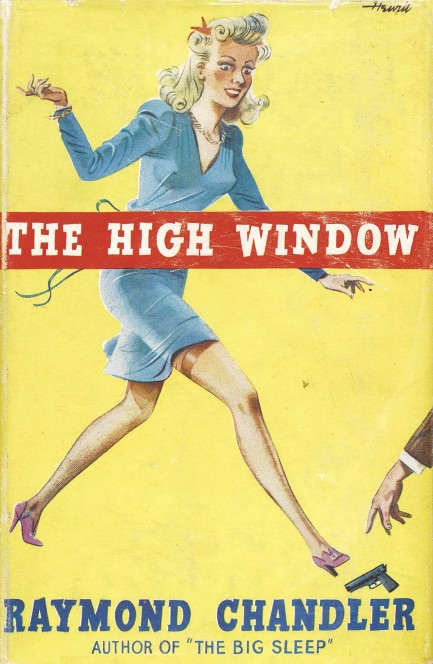

Above: a cover scan of Raymond Chandler's thriller The High Window. This book sold on Sotheby's a while back for more than 5K. It was published in 1943 in identical editions by British imprint Hamish Hamilton and Australia's George Jaboor with cover art that's signed but uncredited inside. It's possibly the work of British painter John Hewitt. He was born in 1922, which would make this an (extremely) early effort. But maybe he was a prodigy. With connections that could get him into the commercial art scene by age twenty-one. Okay, no. Alternatively, this could be the work of Don Hewitt, a British painter born in 1904. He repatriated with his parents to the U.S. in 1907, but could have later worked for an across-the-pond publisher, we suppose. Publishing continued there even during World War II. How Hewitt got his art to London we can't speculate. So, probably not him either. Call it unattributed, then. If you want to know what The High Window is about, check our earlier musings here.

*sigh* That was really unpleasant. I don't know why, but I always assumed it was just a euphemism.

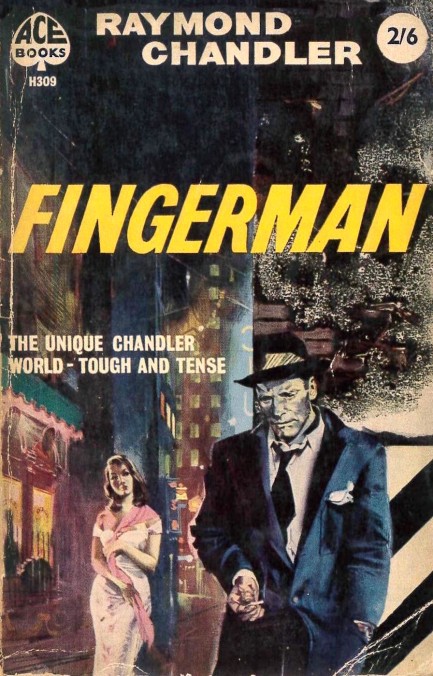

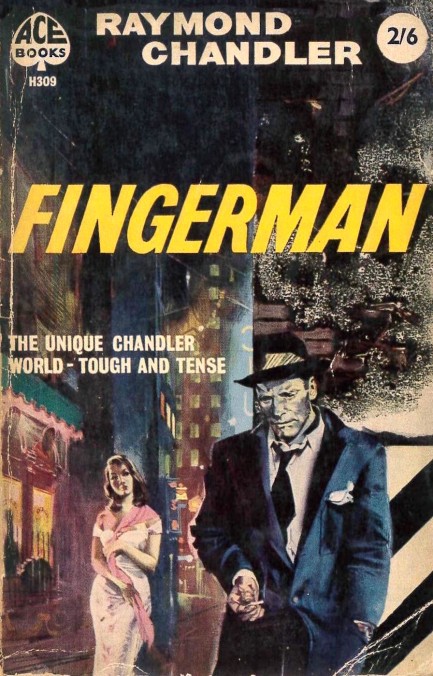

This cover for Raymond Chandler's 1960 story collection Fingerman was painted by an uncredited artist, but once again we're thinking it's Sandro Symeoni on the brush. 1958 to 1960 was when he was working extensively with Ace Books, and this illustration is very much in his style, as we've discussed here and here. The book consists of four offerings: the stories “Finger Man,” which was first published in Black Mask in October 1934, “The King in Yellow,” from the March 1938 issue of Dime Detective Magazine, and “Pearls Are a Nuisance,” also from Dime Detective Magazine, coming in April 1939. The last piece is a Chandler essay titled, “The Simple Art of Murder.” A couple of the aforementioned tales also appeared in Five Sinister Characters. All the stories are good, but we talked about “The King in Yellow” in a bit more detail a while back, so if you're interested feel free to check here.

Yup. We remember being in this condition several times.

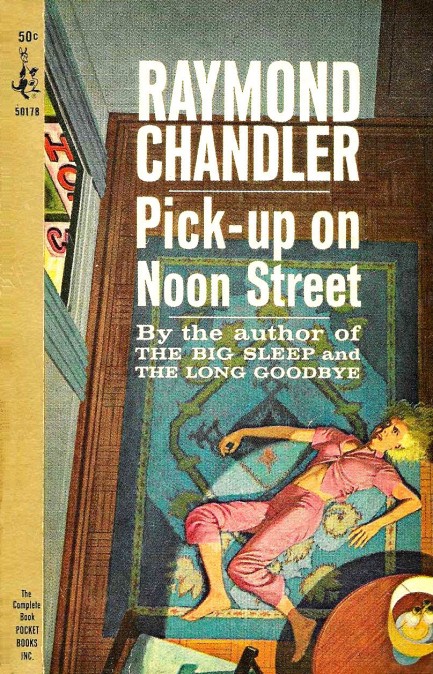

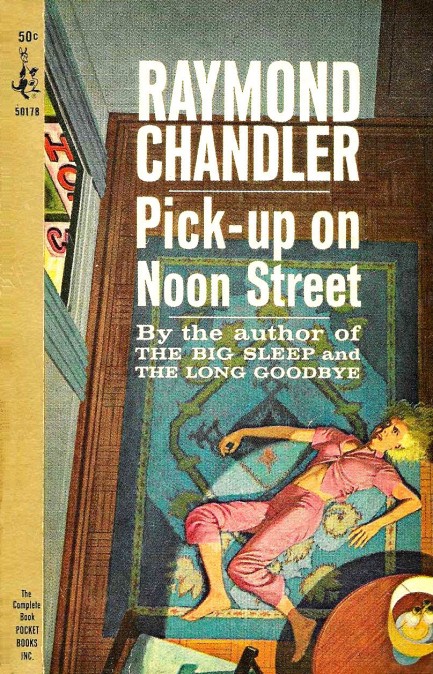

This piece of unusual and excellent cover art was painted for the 1965 Pocket Books edition of Raymond Chandler's four-part anthology Pick-Up on Noon Street, and the scene is personally familiar to us, though it's been years since we got so loaded we ended up insensate. But it happened a few times when we lived in Central America. Ever heard of a liquor called Tic Tack? Steer clear of that stuff. You'll end up a floor tile. The cover specifically illustrates the tale, “Guns at Cyrano's,” in which the hero finds an unconscious blonde in a hotel room. She didn't get that way by doing anything fun, though. The art was painted by Unknown, who's outdone himself here. Seriously, he's put together some masterpieces, but we think this one is top of the heap. You can read more about Pick-Up on Noon Street here.

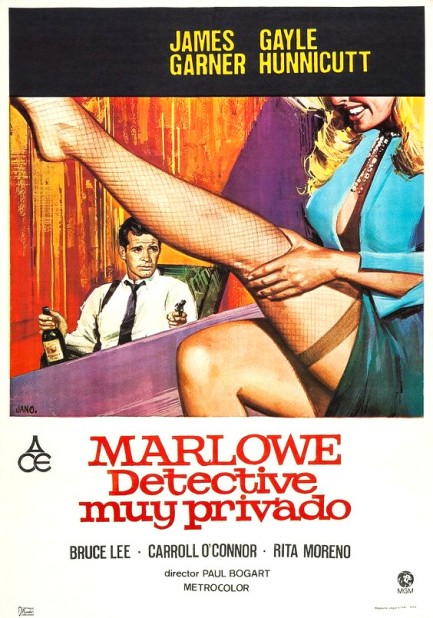

Garner's portrayal of a classic detective feels a lot like a Rockford Files test run.

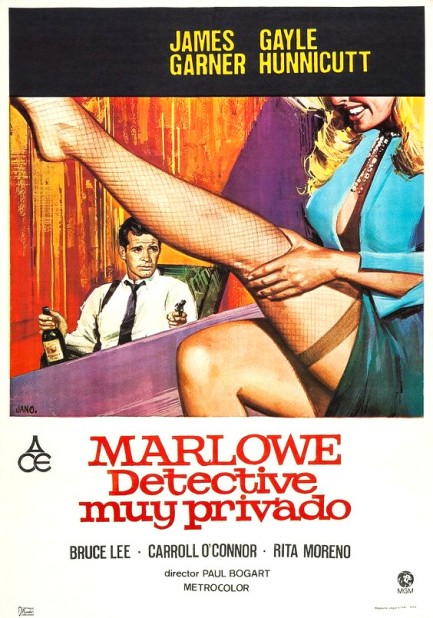

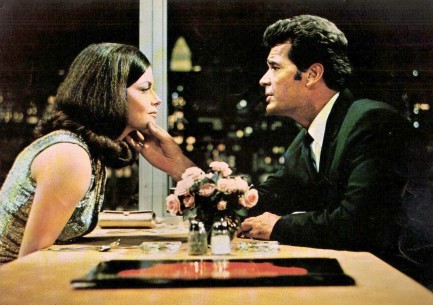

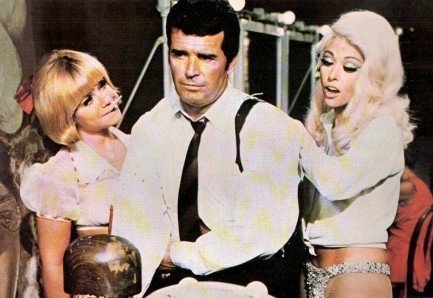

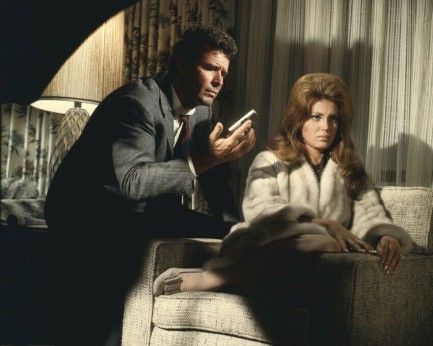

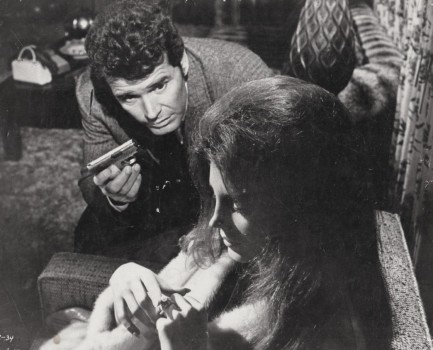

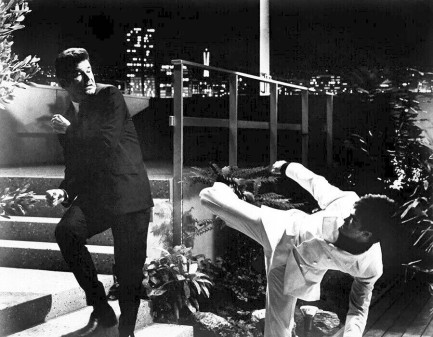

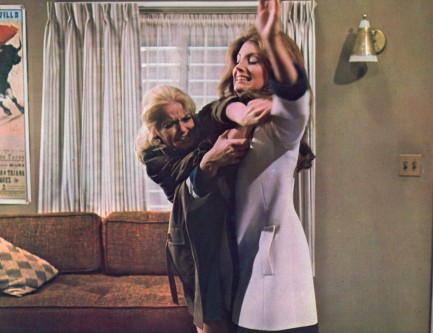

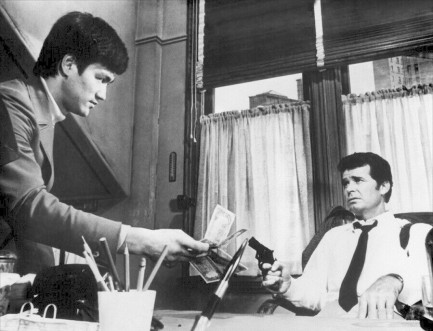

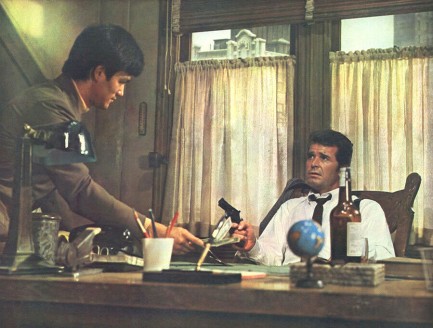

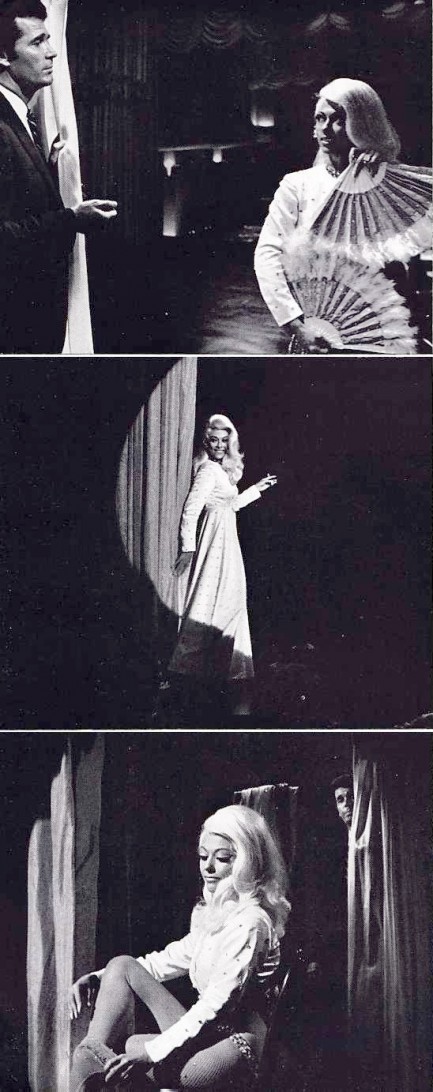

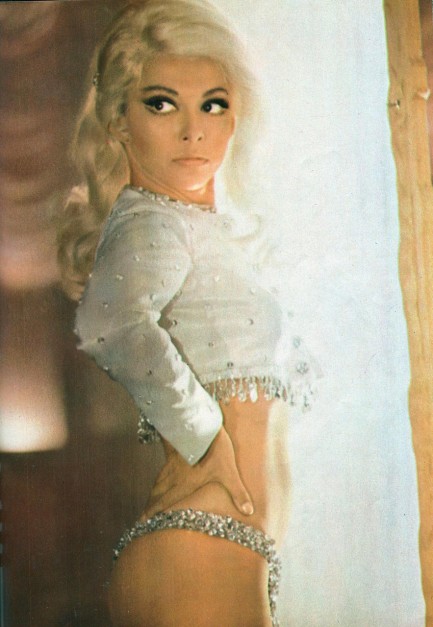

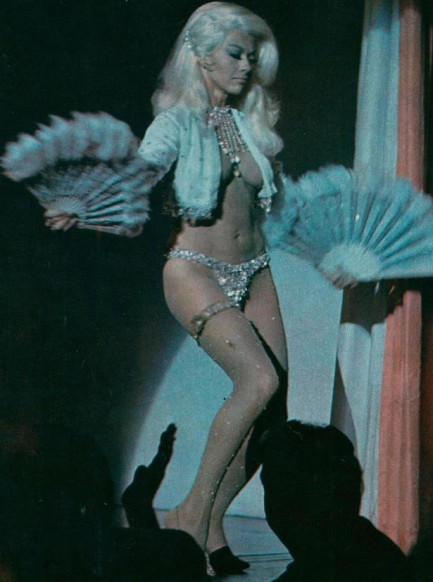

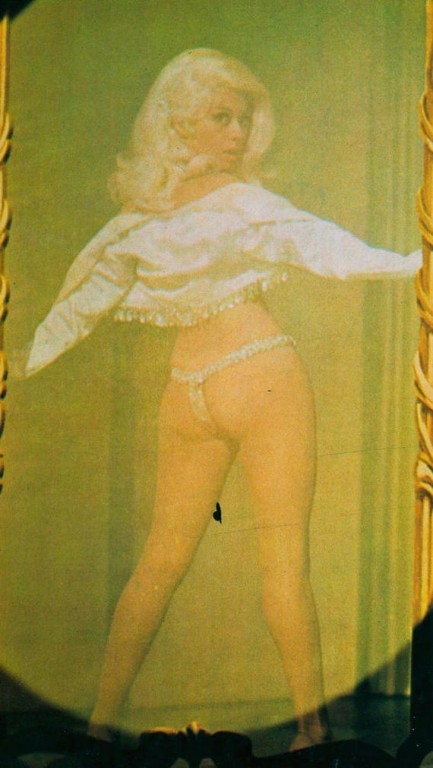

Raymond Chandler's novels have been adapted to the screen several times. One of the lesser known efforts was 1969's Marlowe, which was based on the 1949 novel The Little Sister and starred future Rockford Files centerpiece James Garner as Chandler's famed Philip Marlowe. You see a cool Spanish popster for the movie above, painted by Fernandez Zarza-Pérez, also known as Jano. As usual when we show you a foreign promo for a U.S. movie, it's because the domestic promo isn't up to the same quality. In this case the U.S. promo is almost identical, but in black and white. The choice was clear.

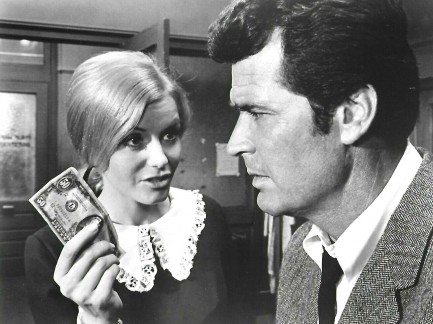

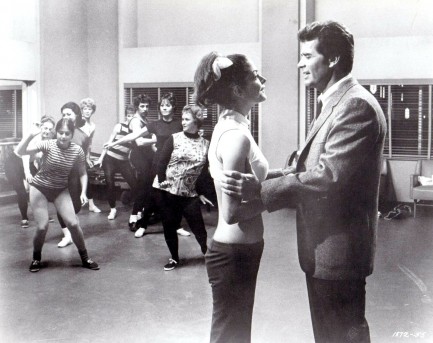

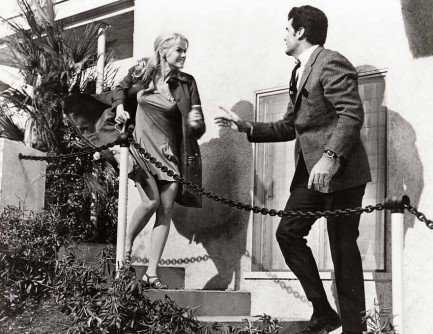

Since you know what to expect from a Chandler adaptation, we don't need to go into the plot much, except to say it deals with an icepick murderer and ties into show business and blackmail. What's more important is whether the filmmakers made good use of the original material, either by remaining true to its basic ideas or by imagining something new and better. They weren't going for new in this case. They were providing a vehicle for the charismatic Garner and ended up with a movie that features him in the same mode he would later perfect in Rockford.

Marlowe has a few elements of note. Rita Moreno plays a burlesque dancer, and it's one of her sexier roles. Bruce Lee makes an appearance as a thug named Winslow Wong. Garner is the star, so it isn't a spoiler to say that Lee doesn't stand a chance. He's dispatched in unlikely but amusing fashion. Overall, Marlowe feels like an ambitious television movie and plays like a test run for Rockford, but it's fun stuff. We recommend it for fans of Chandler, Moreno, Lee, Carroll O'Connor (who co-stars as a police lieutenant), and especially Garner. It premiered in the U.S. in 1969, but didn't reach Spain until today in 1976.

Many miles to go before you Sleep.

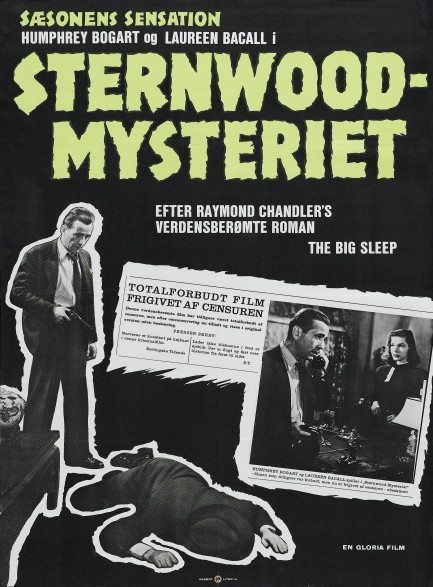

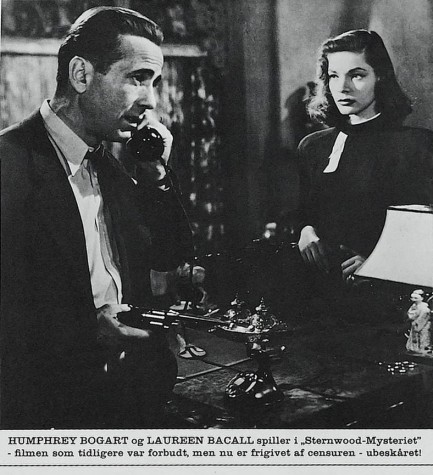

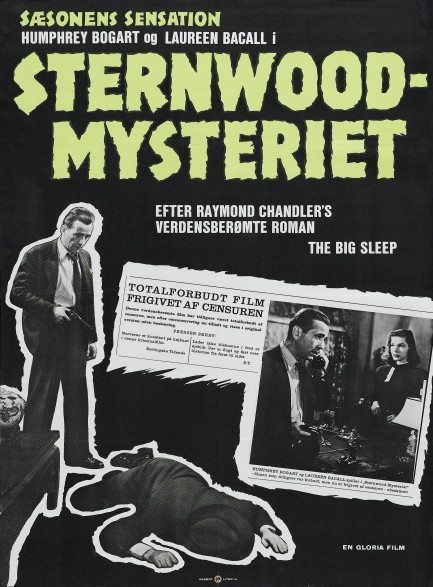

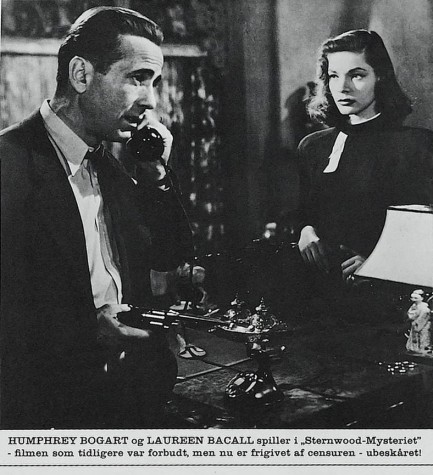

This unusual Danish photo poster was made for Sternwood-mysteriet— Actually, a quick digression. That would be a good pub quiz question, wouldn't it? It could be part of a foreign titles round. “Okay, next question. What is the original title of the film released in Denmark as Sternwood-mysteriet?” Did we ever mention that PSGP has hosted numerous pub quizzes? That's why it came to mind. Funny story: He once lost a bet and had to host one in a Speedo. Anyway, any noir fan would get the question right—Sternwood-mysteriet is better known as The Big Sleep, starring Humphrey Bogart and someone named “Laureen” Bacall.

The movie didn't premiere in Denmark until today in 1962. Why? Apparently it was banned. There could be a couple of different reasons why, or both at once. Bogart's character Sam Spade gets laid—by implication—with a bookstore clerk played by the lovely Dorothy Malone. And a central part of the complex mystery deals with illicit photos, implied to have been pornographic shots of a drugged Martha Vickers. The bookstore seduction isn't in Raymond Chandler's source novel, but the smut photos are. Haven't seen the movie? You should watch it. But carefully.  Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall play in the “Sternwood-Mystery” - the film that was previously banned but is now released by the censor - uncut! Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall play in the “Sternwood-Mystery” - the film that was previously banned but is now released by the censor - uncut!

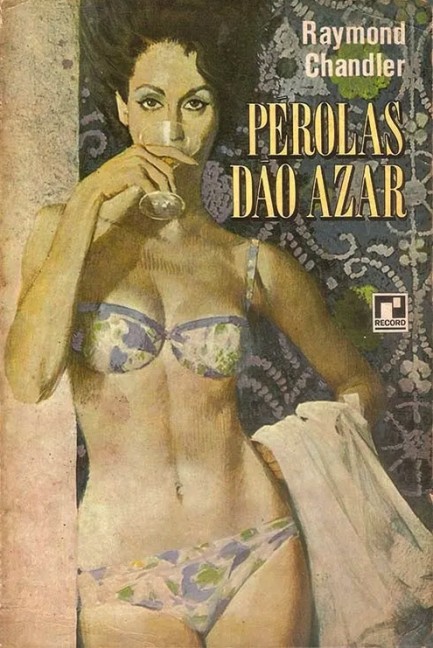

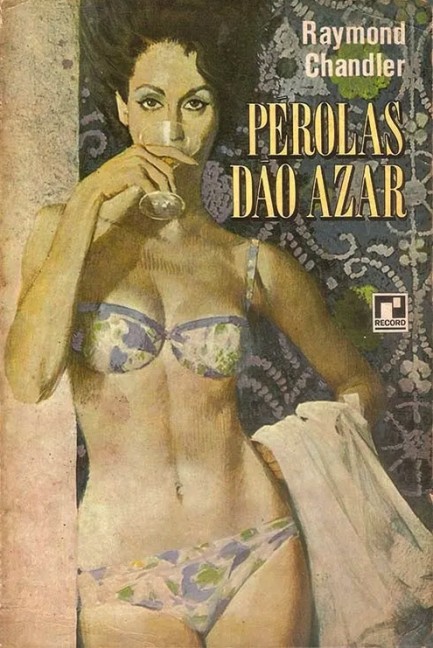

Tall and tan and young and lovely, and when she betrays them, each one she betrays goes, “Argh...”

This interesting piece of art was sent to us by a friend, Leonardo, and it comes from Brazilian publisher Record for Raymond Chandler's Perolas dao azar. The book comprises three Chandler stories, “Pearls Are a Nuisance,” “Finger Man,” and “The King in Yellow,” plus his crime essay, “The Simple Art of Murder.” If you're an avid reader of old literature, “The King in Yellow,” may sound familiar. It was the name of an 1895 anthology by Robert W. Chambers, the best-selling U.S. author of the latter half of the nineteenth century, and the source of certain motifs used in H.P. Lovecraft's Cthulhu Mythos. Chandler's story isn't supernatural, but it does allude to Chambers' work.

The cover art is by Robert McGinnis and was previously used on Shell Scott's 1971 novel Dig That Crazy Grave. Around then Record began spicing up some of its paperbacks with McGinnis art. We don't know if he was compensated for his work. We've talked about this issue before, but long story short, we just can't see an economic win for Record in buying McGinnis's art. In a country as big as Brazil some artist could have painted a nice cover—and cheaply. Probably more cheaply than licensing art from McGinnis. We don't know how it all worked, so we're not saying Record stole the art, but still, you have to wonder. Thanks for sending this over, Leonardo.

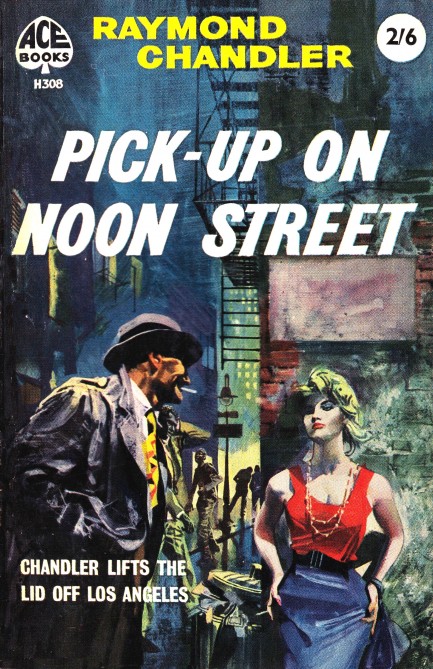

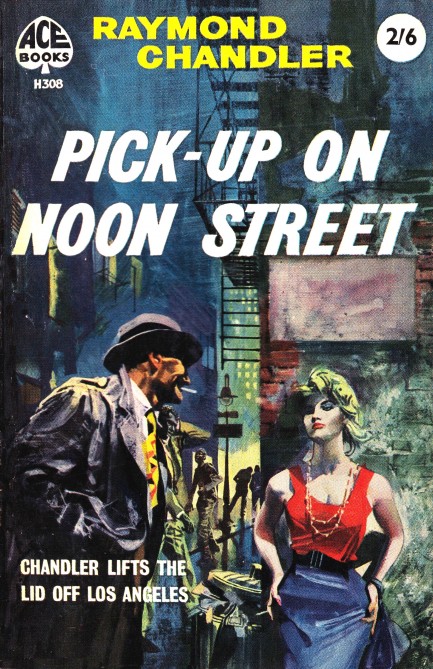

Chandler's Los Angeles is dark day and night.

We're still marveling over Sandro Symeoni's cover work for Ace Books. Each is better than the next. The one above isn't signed, but it's him for sure—well, we think so. It's a beautiful street scene for Raymond Chandler's Pick-Up on Noon Street, not a novel but an anthology of medium length stories originally published in pulp magazines during the 1930s. The collection, comprising four tales set in Los Angeles, first came out in 1950, with this Ace edition appearing in 1960.

The title story was originally published in 1936 as “Noon Street Nemesis” and deals with an undercover narc named Pete Anglish, who accidentally becomes involved in kidnapping and human trafficking. The story is unique because it's set partly in L.A's African American community and it doesn't traffic in the disparaging terminology you usually find under such circumstances. There are good guys and bad guys of all types, with no particular weight given to their backgrounds. It's also a good tale.

In 1935's “Nevada Gas” the title refers to cyanide gas, which comes into play in a specially modified limousine two killers use to execute an unfortunate in the back seat. A Los Angeles tough guy with the excellent name Johnny De Ruse learns that the car was an exact duplicate of the murdered man's actual limousine, which he then entered with no clue the ride would be his last. That's a lot of effort to kill a man, and it intrigues De Ruse greatly, but his curiosity draws the attention of several lethal characters.

In 1934's “Smart-Aleck Kill” a tough Tinseltown detective named Johnny Dalmas tries to solve a murder the cops think was a suicide. The victim was a director of smut movies, but the reasons for his death have to do with something else entirely, and Dalmas has to dodge bullets and overcome duplicity to solve the case.

In 1936's “Guns at Cyrano's” a detective-turned-hotelier named Ted Carmady finds a beautiful blonde who's been knocked out in one of his rooms, and lets his protectiveness lead him into the world of gangsters and fixed prizefights. Cyrano's is a nightclub where the blonde works as a dancer, and where Carmady gets neck deep in murder.

Of the four stories, we liked “Nevada Gas” the best because the character of De Ruse was the most interesting and resourceful, but the leads are all similar—all are basically cousins of Philip Marlowe, kicking ass and taking names in an L.A. rife with hustlers, thugs, wise-ass cops, and corrupt one percenters. If you think of Pick-Up on Noon Street as a sort of Marlowe sampler plate, it should certainly do the job of making you hungry for the main course.

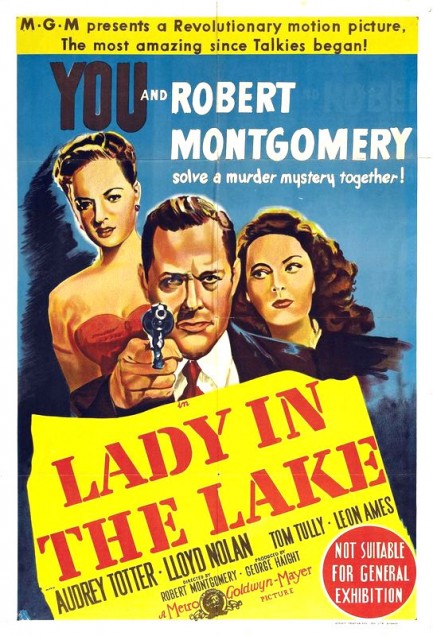

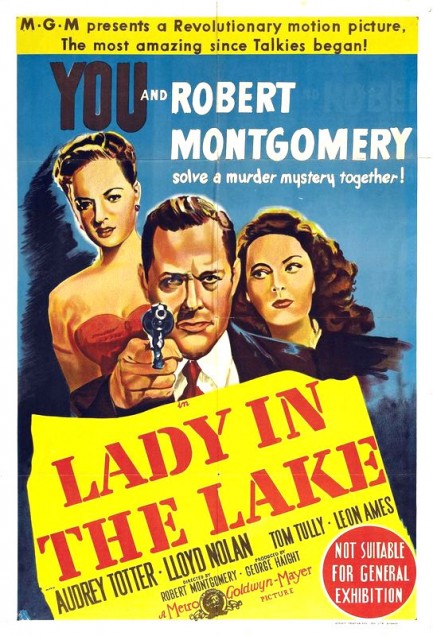

Philip Marlowe tries not to go under for the third time in Lady in the Lake.

Lady in the Lake, for which you see a promo poster above, was the first motion picture shot almost entirely from the visual perspective of a single character. That character is Raymond Chandler's iconic private dick Philip Marlowe, played by Robert Montgomery, who also directed. As both a mystery and a seeing-eye curiosity, this is something film buffs should check out. You won't think it's perfect. Montgomery's version of Marlowe regularly crosses the line from hard-boiled to straight-up asshole, but that's the way these film noir sleuths were sometimes written.

Though the bad attitude is tedious at times, the mystery is interesting, there's plenty of directorial prowess on display from Montgomery, and a bit of unintentional comedy occurs when he gets knocked cold twice in that first person p.o.v. Seriously, Marlowe, you couldn't see those punches coming? We were reclined on the sofa with glasses of wine in our hands and we could have dodged them without spilling a drop. It's all in good fun, though. Every shamus gets forcibly put to sleep now and again.

If the movie has a major flaw it's that co-star Audrey Totter gives a clinic in overdone facial expressions before overcoming these bizarre poker tells to finally settle into normal human behavior around the halfway mark. Despite that bit of weirdness, film noir fans will like this. Those new to the genre maybe will find it too strange to fully enjoy. But it's indisputably a landmark, and that's worth something. Lady in the Lake premiered in London in late 1946, and went into general release in the U.S. today in 1947.

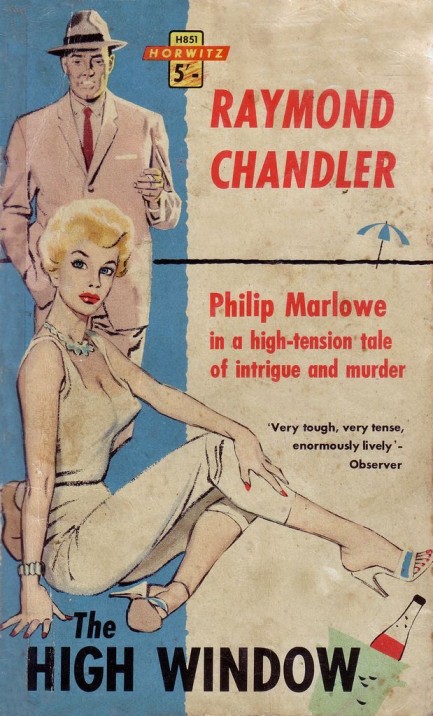

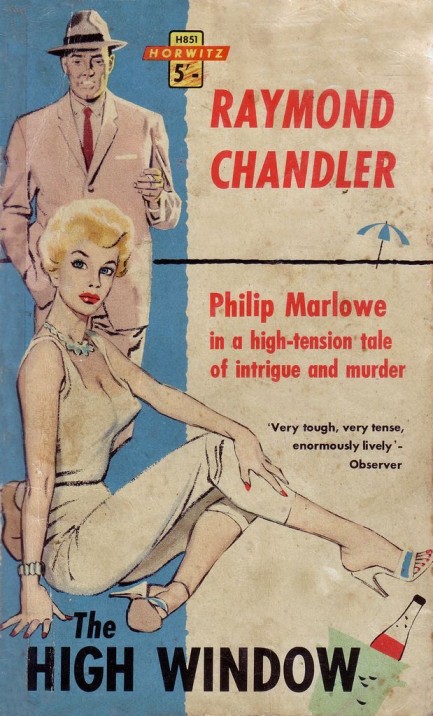

Horwitz unclutters the view on Chandler's classic.

Above is a nice alternate cover for Raymond Chandler's The High Window from Australia's Horwitz Publications, circa 1961. It's a cleaner, less plot revealing, and less controversial piece than the battered wife cover put out by American publishers Pocket Books in 1955. We found it on Flickr, so thanks to the original uploader. Sadly, the art is uncredited, which is the way Horwitz generally did business, those damn Aussies.

That's not exactly the type of apology I had in mind, but I guess it'll have to do.

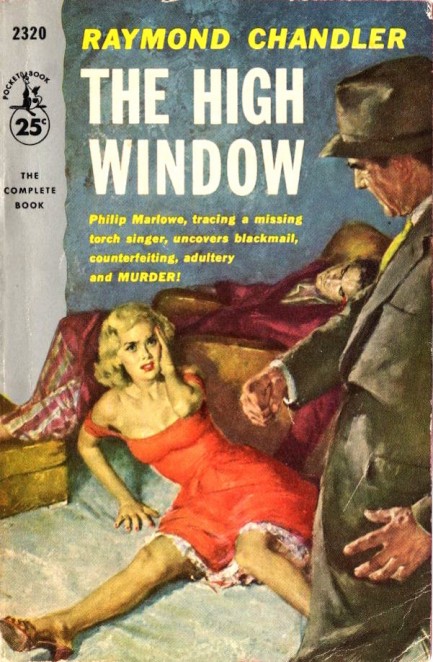

This is an interesting piece of cover art for Raymond Chandler's third Phillip Marlowe thriller The High Window, the novel that was filmed as Time To Kill with Marlowe rewritten as another character, then filmed several years later as The Brasher Doubloon, with Marlowe restored. The book originally appeared in 1942, and the above painting by James Meese fronted Pocket Books' 1955 edition. Without reading it, one might assume this is Marlowe being punchy, but it's actually a bad guy named Alex Morny laying into his wife/accomplice-in-crime Lois. In the narrative Marlowe is lurking nearby, but he doesn't intervene because he's contemptuous of criminals, whether male or female.

Marlowe generally sticks up for underdogs. He particularly hates the abuse of authority. When two cops give him a hard time for being uncooperative he reminds them why he's that way by refreshing their memories concerning a case he investigated where a spoiled heir shot his secretary then killed himself. The cops closed that case with the official finding that the opposite had happened—the secretary had shot the heir before turning the gun on himself, and they did it to spare the heir's powerful father public embarrassment. The cops ask an annoyed Marlowe what difference it makes. They were both dead, so who cares?

Marlowe: “Did you ever stop to think that [his] secretary might have had a mother or a sister or a sweetheart—or all three? That they had their pride and their faith and their love for a kid who was made out to be a drunken paranoiac because his boss's father had a hundred million dollars? Until you guys own your own souls you don't own mine. Until you guys can be trusted every time and always, in all times and conditions, to seek the truth out and find it and let the chips fall where they may—until that time comes [I will not trust you].”

We've paraphrased a bit because the specifics aren't needed here, but it's a great speech. Countless sociological and criminological studies reveal that justice is still meted out mildly upon some groups, and severely upon others, more than half a century after Chandler wrote those lines. And the fact that a two-tiered justice system exists is so accepted these days it's banal to even point it out. But Marlowe tended to rail against corruption, even if doing so caused him problems. To resist was part of his personal code, and the code is part of what makes him such an interesting character. If you want to know more about The High Window you can find an extra detail or two in our write-up on Time To Kill here.

|

|

The headlines that mattered yesteryear.

1945—Churchill Given the Sack

In spite of admiring Winston Churchill as a great wartime leader, Britons elect

Clement Attlee the nation's new prime minister in a sweeping victory for the Labour Party over the Conservatives. 1952—Evita Peron Dies

Eva Duarte de Peron, aka Evita, wife of the president of the Argentine Republic, dies from cancer at age 33. Evita had brought the working classes into a position of political power never witnessed before, but was hated by the nation's powerful military class. She is lain to rest in Milan, Italy in a secret grave under a nun's name, but is eventually returned to Argentina for reburial beside her husband in 1974. 1943—Mussolini Calls It Quits

Italian dictator Benito Mussolini steps down as head of the armed forces and the government. It soon becomes clear that Il Duce did not relinquish power voluntarily, but was forced to resign after former Fascist colleagues turned against him. He is later installed by Germany as leader of the Italian Social Republic in the north of the country, but is killed by partisans in 1945. 1915—Ship Capsizes on Lake Michigan

During an outing arranged by Western Electric Co. for its employees and their families, the passenger ship Eastland capsizes in Lake Michigan due to unequal weight distribution. 844 people die, including all the members of 22 different families. 1980—Peter Sellers Dies

British movie star Peter Sellers, whose roles in Dr. Strangelove, Being There and the Pink Panther films established him as the greatest comedic actor of his generation, dies of a heart attack at age fifty-four.

|

|

|

It's easy. We have an uploader that makes it a snap. Use it to submit your art, text, header, and subhead. Your post can be funny, serious, or anything in between, as long as it's vintage pulp. You'll get a byline and experience the fleeting pride of free authorship. We'll edit your post for typos, but the rest is up to you. Click here to give us your best shot.

|

|

Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall play in the “Sternwood-Mystery” - the film that was previously banned but is now released by the censor - uncut!

Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall play in the “Sternwood-Mystery” - the film that was previously banned but is now released by the censor - uncut!