Why, thank you, ladies, I am a goat, and proud of it. Um—you mean greatest of all time, right?

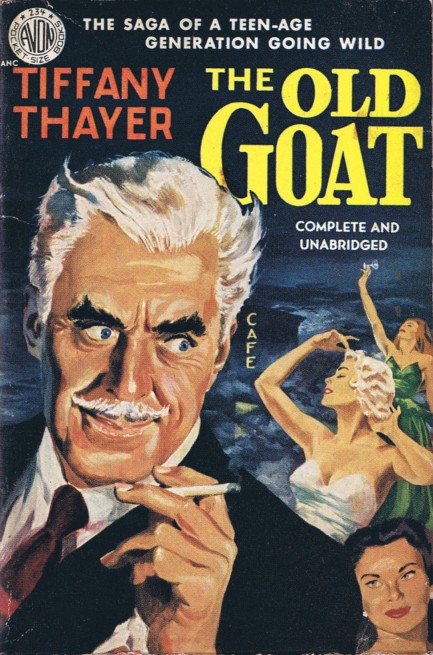

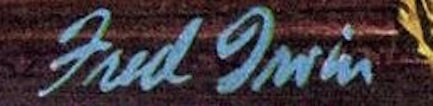

We've been having an ongoing conversation with the Pulp Intl. girlfriends about the word, “cougar,” when used to refer to older women who chase younger men. They say there's no male equivalent. If you're an older man chasing after young women, you're just a man, we were told. We think cougar is kind of a fun slang term, but then we are neither women, nor women in that age range, so our opinion doesn't actually count. Anyway, we came across this cover for Tiffany Thayer's 1950 novel The Old Goat, and we're going to go with "goat" as a term for a male cougar. And no, not “greatest of all time.” Just goat. We'd like it to catch on, but sports fans have a firm hold on it at the moment. However, we'll do our part to change that if you do yours. The art on this, by the way, is by an unknown, but the rear cover and several interior illustrations are by Lyle Justis.

Update: we recently found ourselves in a group of six women, and we'd all had a few drinks, so it seemed like a good time to throw this question to the committee. The preferred term they came up with for an older man who chases after young women was: honey badger. Gotta say, that works really well.

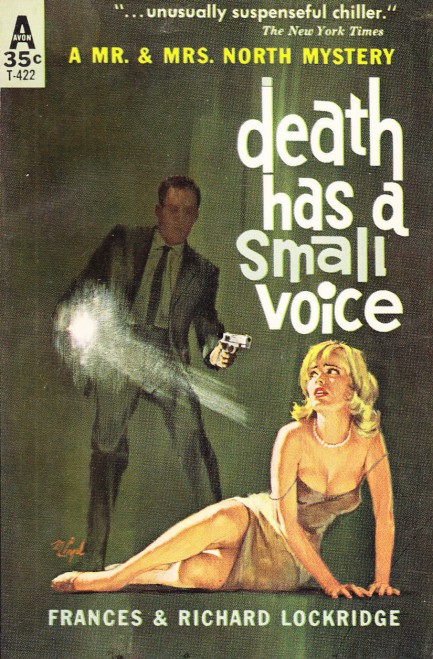

Speak softly but carry a big gun.

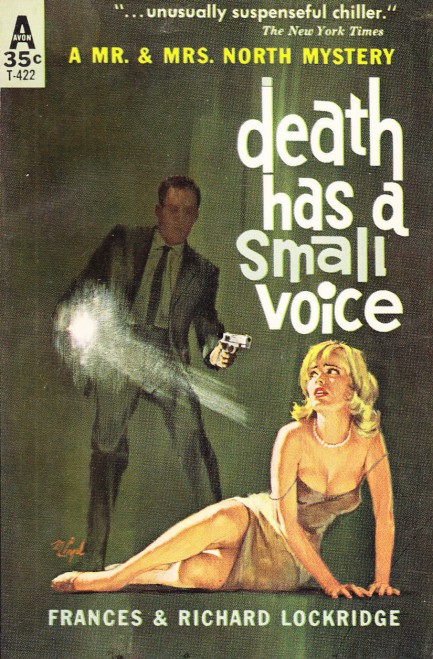

Mort Engel art fronts this Avon edition of Frances and Richard Lockridge's Death Has a Small Voice, a book we were eager to read because of the promise of The Norths Meet Murder, the debut tale in the Mr. and Mrs. North series of which the above book is a part. That promise is not fully realized here. Perhaps it's our fault for not reading the series in order. Seventeen entries in, maybe the Lockridges were trying to shake up their formula a bit. But we don't have much control over which books in a series are obtainable for us. We buy what's out there. In this tale Pamela North is kidnapped in the first few pages, and because she's isolated, the story misses the entertaining dialogue she provided in the debut. That makes the “small voice” of the title ironic—it's supposed to refer to the whispering kidnapper, but it's Pamela whose voice is diminished.

But it's a readable book anyway, even with Pamela ruminating in the dark for multiple chapters. Basically, someone has murdered an author named Hilda Godwin after becoming aware that he's been negatively portrayed in the draft of her upcoming novel. Through circumstances we won't detail here, she manages to record her own attack and killing. The recording is mailed to Gerald North's literary agency and the killer is desperate to retrieve it before anyone hears it. But the recording falls into Pamela's hands, and when the killer comes for it she manages to hide it. So the killer kidnaps her, planning to make her reveal the hiding place.

These are treacherous circumstances, and anything less than a horrible ordeal for Pamela would be unrealistic, which is why it's a good plot move by the Lockridges to have her escape almost immediately. From that point she's lost in a forest, while her husband and the cops are trying to fit the puzzle pieces that might lead to her rescue. Since the Lockridges are good writers this all works fine, but because Pamela seems to us to be the main attraction of series (based on the mere two books we've now read), we had little choice but to come away a bit disappointed. But like we said, after a while authors will try new ideas. What we'll try is to find book two in the North series Murder Out of Turn at a reasonable price, international shipping included. If we do we'll report back.

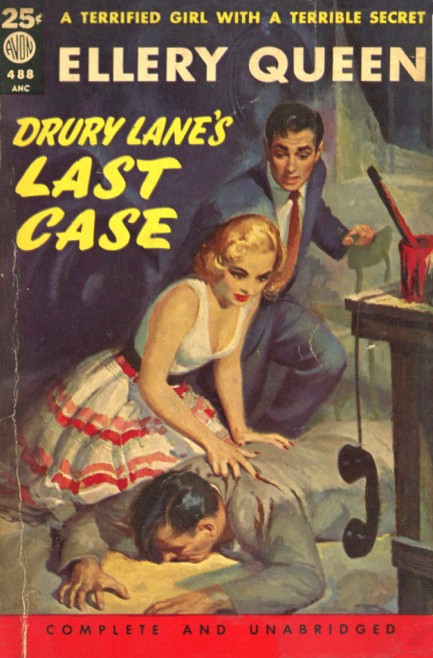

I'm no doctor, but if a man isn't moving and isn't snoring, he's probably a corpse.

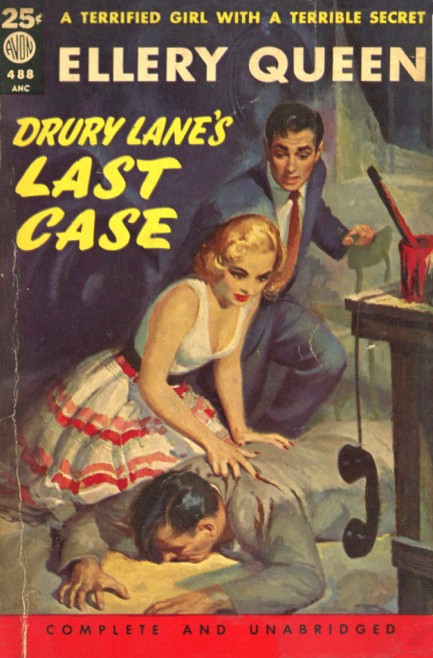

Above: a cover for Drury Lane's Last Case by Ellery Queen, who was actually Daniel Nathan partnering with Manford Lepofsky. It's originally 1933, with the above edition from Avon coming in 1952.

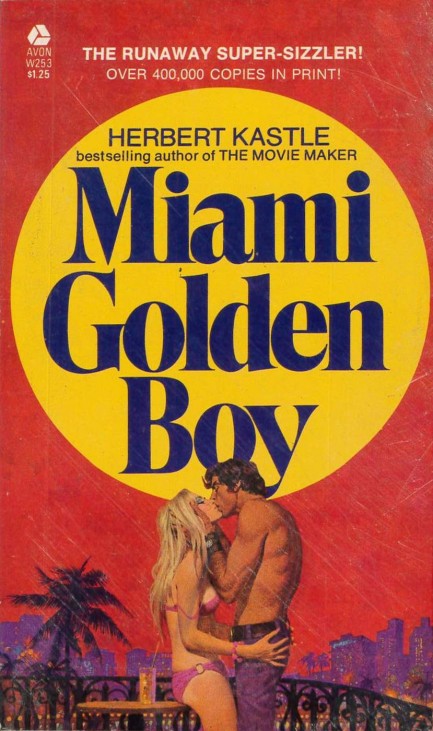

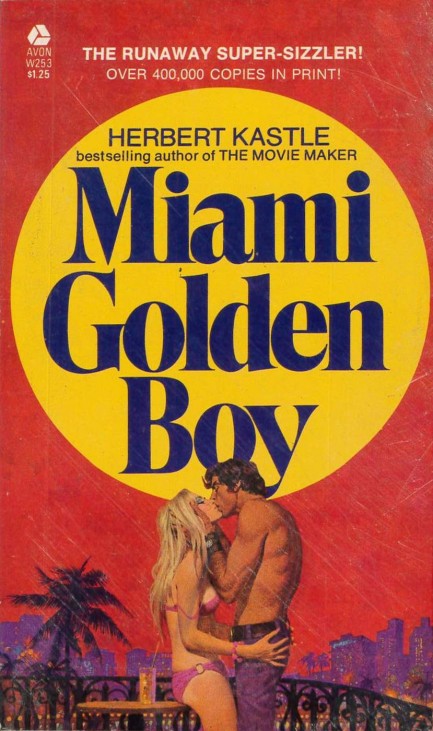

Miami, Florida: sunny weather, shady people.

We shared a cover for and talked about Herbert Kastle's 1970 thriller Miami Golden Boy back at the beginning of this year. Above you see the 1971 paperback edition from Avon. We could have bought this version, but we were too taken by the hardback's Barbara Walton sleeve art. The effort above, on the other hand, is uncredited, which is always a shame. Miami Golden Boy was good, if a bit forced (the main character's last name is Golden, to give you an idea how Kastle thinks), but the execution is at a high level. You can read more about the book here.

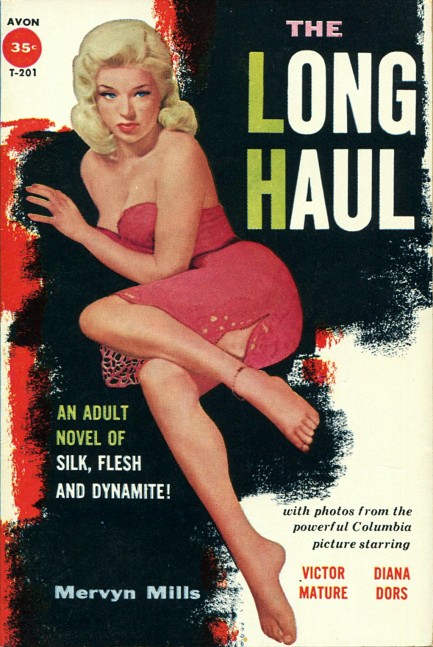

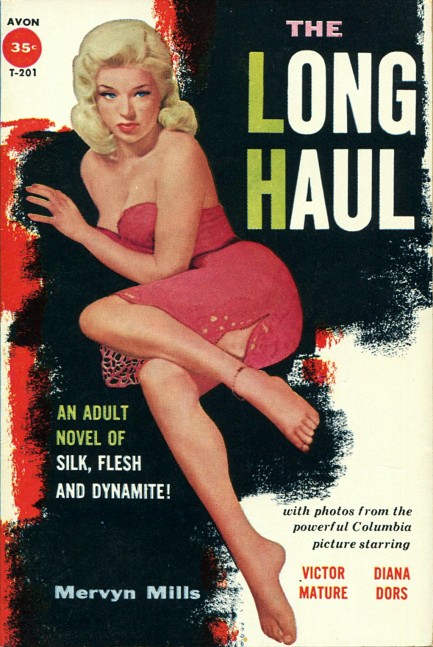

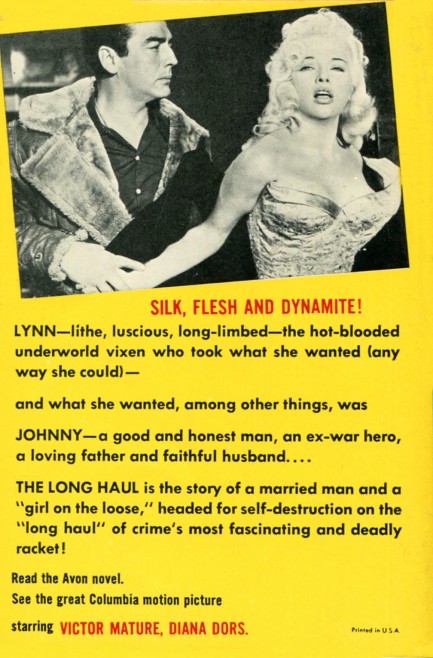

Victor Mature offers a ride and accidentally opens a Dors to big trouble.

Above is a nice cover for the movie tie-in edition from Avon Publications of The Long Haul by Mervyn Mills, which is about a trucker who gives a ride to a gangster's moll and as a result has to deal with numerous life threatening problems. It was published in 1957 and immediately adapted to the big screen, with the movie starring Victor Mature and Diana Dors appearing the next year. The art on this, which we think is great, is modeled after the movie poster and is unattributed, possibly because it's a photo-illustration, though we can't 100% sure on that.

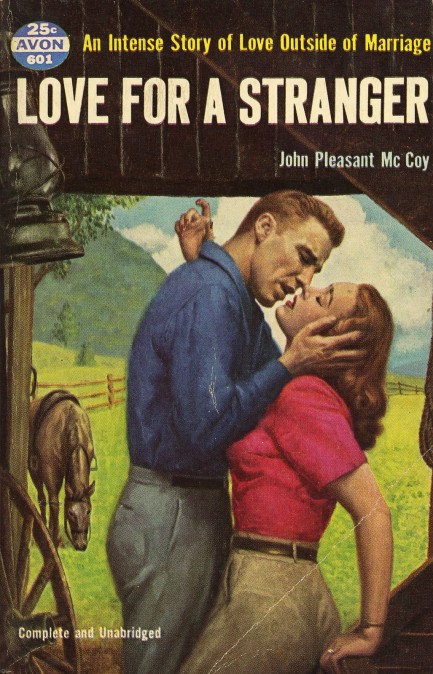

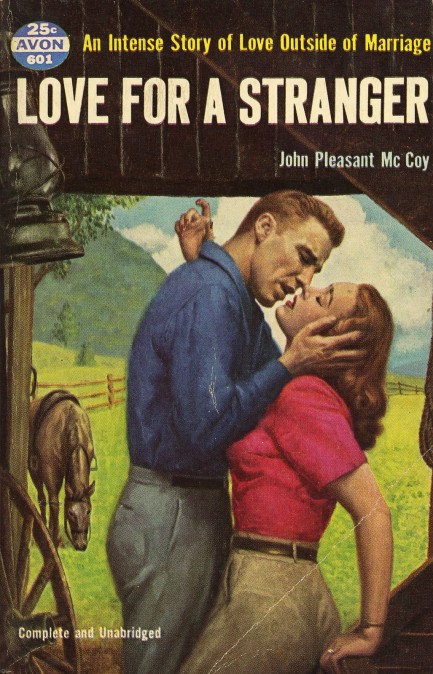

There was a girl once. I loved the entirety of her head. I never thought I'd get over her, but I love your head even more.

What is it with these head grabbers? We suppose certain paperback artists thought it conveyed passion to have a man handle a woman's cranium like a bowl of salad, but we have personally never done that. Is something wrong with us? Should we be more phrenologically inclined? We'll ask our girlfriends. Meanwhile, see the cover that spawned our callback here.

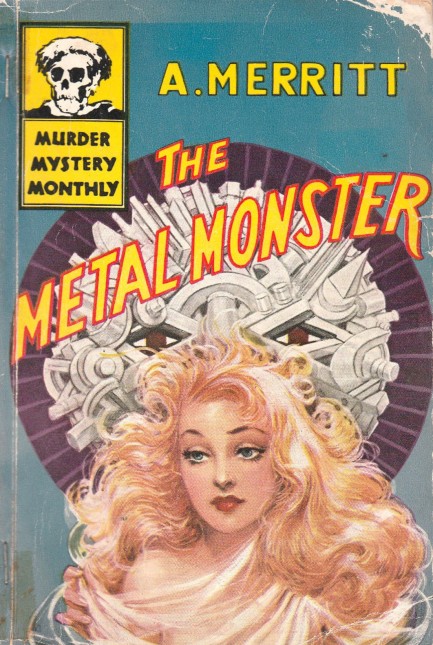

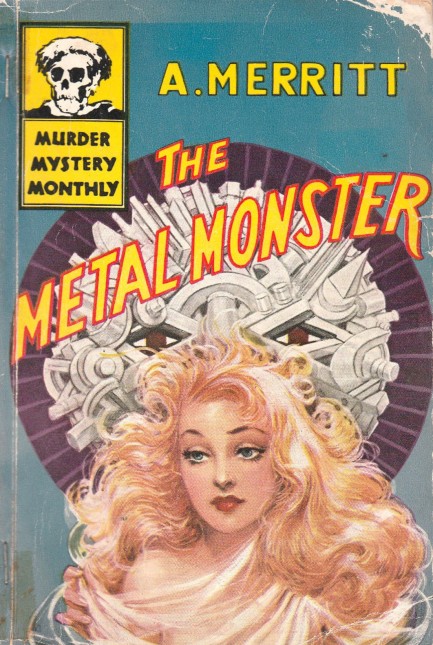

The Metal Monster is science fiction as a mind-altering trip.

We usually read novels from the ’40s, ’50s, and ’60s, but we took a trip to the heart of the pulp era with Abraham Merritt's The Metal Monster, which made its first appearance as a serial in Argosy All-Story Weekly in 1920. The above paperback came in 1946 from Avon Publications' Murder Mystery Monthly #41, and has cover art by the always interesting Paul Stahr, who worked extensively with Avon during this period. You can click his keywords at bottom and see all four of the covers by him we have in the website. There are also interesting covers by other artists on later editions of The Metal Monster. We'll try to show you a couple of those later. In Merritt's tale, four explorers travel into an uncharted Himalayan valley and subsequently are trapped by what lives in the area—Persian soldiers seemingly stuck in time, or whose traditions have gone unchanged for two thousand years. There's something else in the valley too—a shimmering goddess creature named Norhala and her metal swarm, which is usually a blizzard of small geometrical shapes, but can collect into forms as needed, for example a towering monster with six whiplike arms that scythe through the ranks of the Persians, ripping them to shreds. While Norhala has some control over the swarm, we later learn that the creatures came from the stars, feed on sunlight, and eventually eradicate biological life on every planet they colonize. So that's not good. Merritt's prose brings to mind H.P. Lovecraft, because he similarly tasks himself with describing the indescribable. Lovecraft fans know what that means—the creatures in his mythos are so mindbending as to drive humans insane merely to gaze upon them. Lovecraft challenged himself to describe those beings, and much of the horror in his writing derives from those attempts. But he sometimes took his built-in escape hatch too, ultimately saying the creatures simply were so inhuman they couldn't be described. Merritt faces the same challenge, and in his descriptions usually manages to be vivid yet vague: Where the azure globe had been, flashed out a disk of flaming splendors, the very secret soul of flowered flame! And simultaneously the pyramids leaped up and out behind it—two gigantic, four rayed stars blazing with cold blue fires. The green auroral curtainings flared out, ran with streaming radiance—as though some spirt of jewels had broken bonds of enchantment and burst forth jubilant, flooding the shaft with its freed glories. The tale is filled with psychedelia like the example above, though it does get more concrete in parts, like here: [They] lifted themselves in a thousand incredible shapes, shapes squared and globed and spiked and shifting swiftly into other thousands as incredible. I saw a mass of them draw themselves up into the likeness of a tent skyscraper high; hang so for an instant, then writhe into a monstrous chimera of a dozen towering legs that strode away like a gigantic headless and bodiless tarantula in steps two hundred feet long. I watched mile-long lines of them shape and reshape into circles, into interlaced lozenges and pentagons—then lift in great columns and shoot through the air in unimaginable barrage. Honestly, all these hyper-detailed descriptions get tedious at times, as does the pervasive incredulity of Merritt's narrator Dr. Walter T. Goodwin. We get that he's dumbfounded, but the human mind has an amazing capacity to normalize that which it sees constantly, therefore we'd prefer if Goodwin weren't repeatedly floored by everything he encounters. That way, when he finally learns what form the metal swarm actually takes—that of a vast city—we readers can finally be truly amazed. However, when we think of The Metal Monster as an Argosy serial circa 1920, it's visionary, and we imagine it must have been intensely gripping. Merritt may merit more exploration.

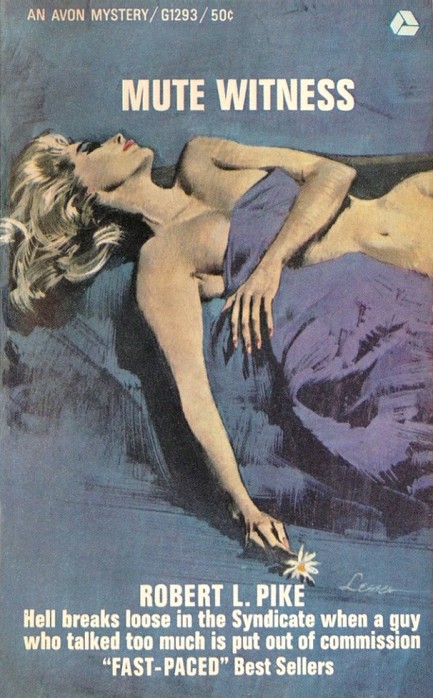

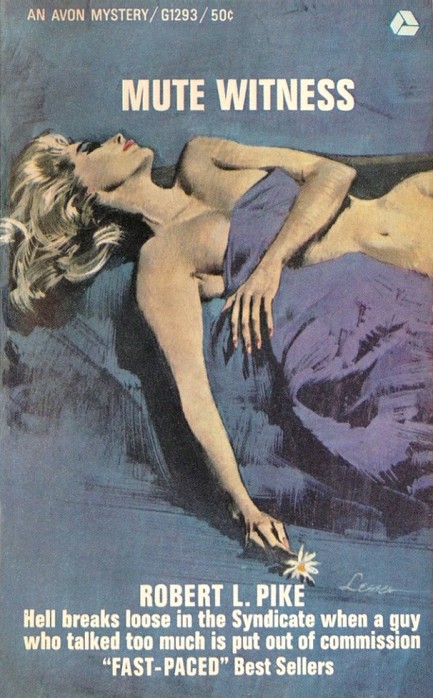

When you promise to carry a secret to the grave make sure nobody takes you literally.

We didn't know Robert L. Pike's Mute Witness was the source material for the film classic Bullitt when we picked it up, but indeed it is. In the book the main character is named Clancy not Bullitt, and the lead villain is named Rossi not Ross, but the central idea remains—a mob turncoat figures out a clever way to escape free and clean from his employers by using the police as unwitting accomplices. We checked online and someone was selling the first edition hardback of this for $2,000. To which we say dream on. While Mute Witness is a notable book because of the movie it spawned, it isn't a particularly brilliant one. Solid, we'd say. Entertaining. Fast paced. But it also has lines like, “Clancy felt the old familiar tingle run along his spine like barefoot mice,” as if mice usually wear stiletto heels. But as far as it being a fun read, the requirement was met. We recommend it. It was originally published in 1963, with this edition from Avon coming in 1966 with Ron Lesser cover art.

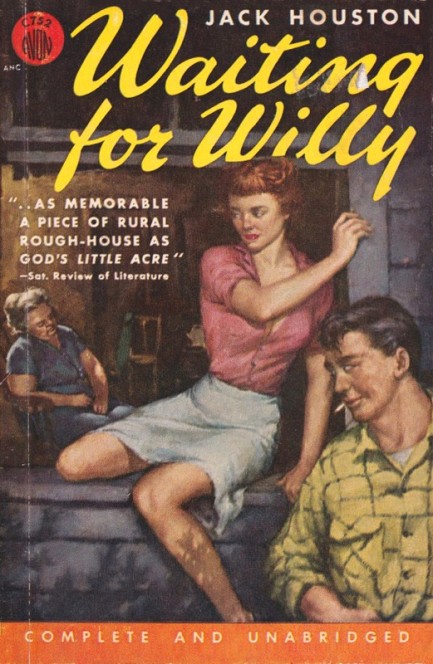

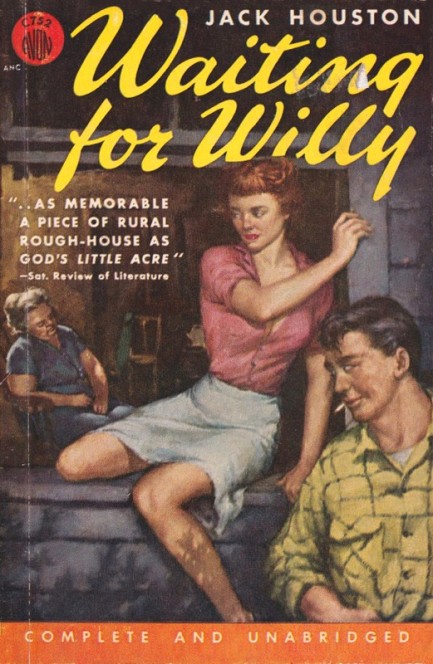

It's about time you got here Clarence Joe—I'm like to die of desperation.

We can't tell you for sure, since Jack Houston's 1952 novel Waiting for Willy dates from well before were born, but we suspect “willy” was a slang term for penis even back then. We think so only because we keep finding what we thought were contemporary slang terms in these old books. We wish we'd thought before now to make a list. You'd be surprised. Apart from some hip-hop expressions—and even including many of those—the slang already existed and was used in the same context. Of course, authors often borrowed terminology from early- and mid-century African American vernacular, which makes the whole process circular, sort of. We'll wait for a comprehensive study on the subject from you linguists out there, and as the cover shows, anticipation is the best part. The art on this is by George Erickson, who you can see more of by clicking his keywords below.

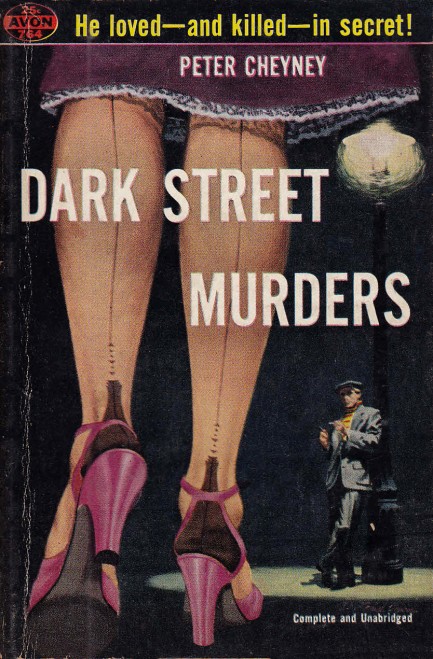

Well, well. I never really believed the stories, yet here you are in the flesh—the fifty foot woman.

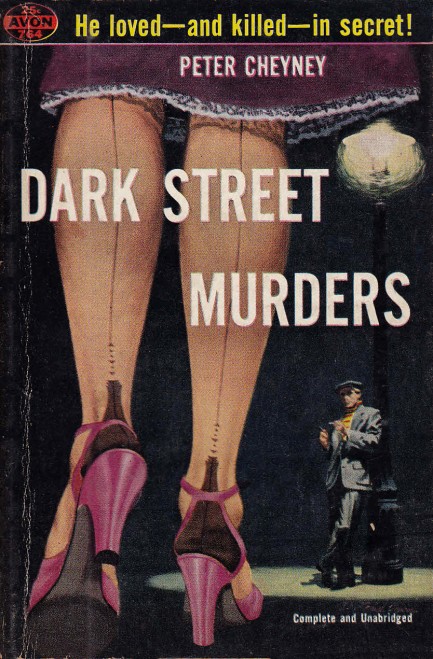

Above: interesting perspective and wonderful execution from artist Fred Irvin for Avon Publications' 1957 paperback edition of Peter Cheyney's 1944 novel Dark Street Murders, aka The Dark Street. Other sites have this cover as unattributed, but we're sure it's Irvin. His signature is dim, but visible. We grabbed one from another piece of his for confirmation.

|

|

The headlines that mattered yesteryear.

1945—Churchill Given the Sack

In spite of admiring Winston Churchill as a great wartime leader, Britons elect

Clement Attlee the nation's new prime minister in a sweeping victory for the Labour Party over the Conservatives. 1952—Evita Peron Dies

Eva Duarte de Peron, aka Evita, wife of the president of the Argentine Republic, dies from cancer at age 33. Evita had brought the working classes into a position of political power never witnessed before, but was hated by the nation's powerful military class. She is lain to rest in Milan, Italy in a secret grave under a nun's name, but is eventually returned to Argentina for reburial beside her husband in 1974. 1943—Mussolini Calls It Quits

Italian dictator Benito Mussolini steps down as head of the armed forces and the government. It soon becomes clear that Il Duce did not relinquish power voluntarily, but was forced to resign after former Fascist colleagues turned against him. He is later installed by Germany as leader of the Italian Social Republic in the north of the country, but is killed by partisans in 1945. 1915—Ship Capsizes on Lake Michigan

During an outing arranged by Western Electric Co. for its employees and their families, the passenger ship Eastland capsizes in Lake Michigan due to unequal weight distribution. 844 people die, including all the members of 22 different families. 1980—Peter Sellers Dies

British movie star Peter Sellers, whose roles in Dr. Strangelove, Being There and the Pink Panther films established him as the greatest comedic actor of his generation, dies of a heart attack at age fifty-four.

|

|

|

It's easy. We have an uploader that makes it a snap. Use it to submit your art, text, header, and subhead. Your post can be funny, serious, or anything in between, as long as it's vintage pulp. You'll get a byline and experience the fleeting pride of free authorship. We'll edit your post for typos, but the rest is up to you. Click here to give us your best shot.

|

|