The forecast is looking very good.

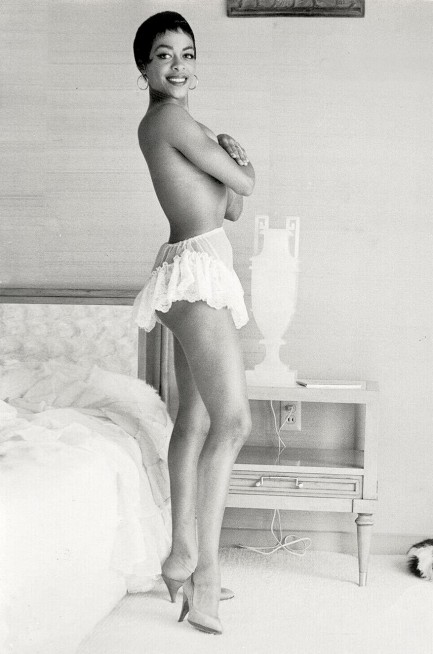

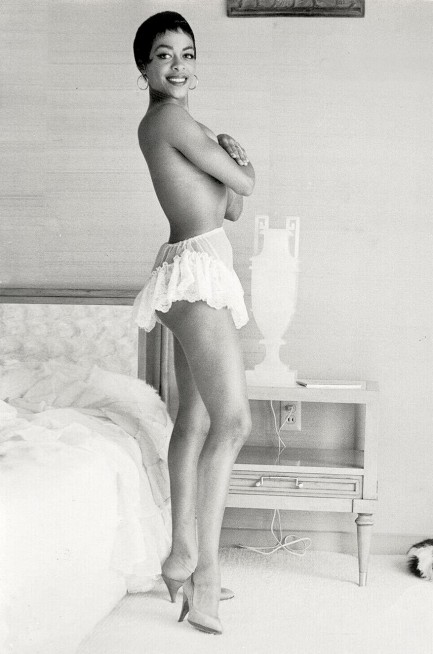

Above: a really nice shot of model and showgirl La Raine Meeres made by famed pin-up photographer Bunny Yeager around 1957. We can't tell you much about Meeres, except that she danced in Cab Calloway's Cotton Club Revue and this shot was made when the show passed through Yeager's base of Miami. Yeager was an early standard bearer for inclusivity, and made a point of working with women of color when few photographers were interested. We'll keep an eye out for more of the marvelous Meeres.

Lines in the sand have a way of getting crossed.

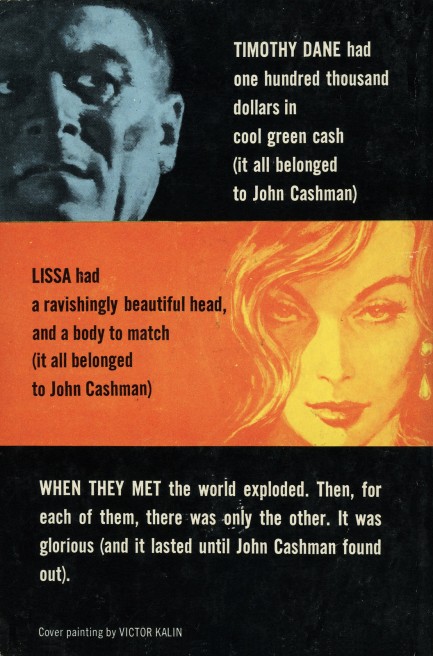

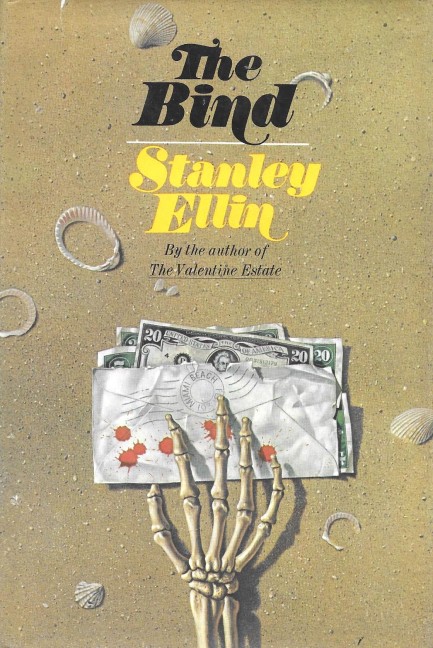

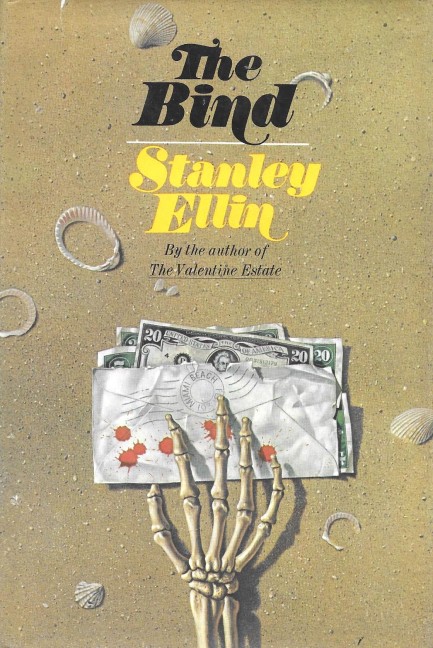

Considering our website's focus on beautiful art, you must be asking how we came to read Stanley Ellin's 1970 novel The Bind, with its beige post-GGA cover treatment by Joe Lombadero. What happened was we decided to watch the 1979 Farrah Fawcett movie Sunburn, but stopped during the opening credits when we saw that it was based on a novel. We'd decided to see the movie because it was helmed by cult director Richard C. Sarafian, and also because its premise interested us, but we figured that premise was probably more fully and interestingly developed in the source novel. We won't know for sure until we watch the film, but it's pretty much a given when you compare literature to cinema.

Here's the premise: insurance investigator Jake Dekker needs to get close to a secretive family to disprove a verdict of accidental death and save his employers a $200,000 payout, so he rents a house in their tony Miami enclave and hires an actress to pose as his wife. The family would be suspicious of a single man, but not a married couple. He's carried out similar scams and worked with the same actress over and over, but when she can't make the gig she instead sends down-on-her-luck colleague Elinor Majeski as a replacement. The fake wife aspect of Jake's scheme immediately gets complicated, both because this new actress is smarter and more curious than is convenient, and because she's unusually lovely. Uh oh. Professional comportment—out the window.

Ellin pushes his ripe premise for all it's worth. Jake insists on realism, which involves he and Elinor getting comfortable around each other, whatever intimate circumstances might arise. The only line they aren't to cross is sleeping in the same bed. Heh. How long do you think that lasts? Actually, it lasts a long while. Jake's shell is hard. He's borderline mean to Elinor, and therein lies the balancing act in the narrative. He's mean, but occasionally charming. Ellin's writing treads that crucial line well, but the book is overlong and its climax goes in a direction we didn't like. But we'd read him again. In any case, now we'll have to see what the filmmakers did with Farrah in the role of Elinor. Charles Grodin co-stars, so we expect the movie to be a bit silly, but who can resist Farrah?

Sometimes you can't win no matter what you do.

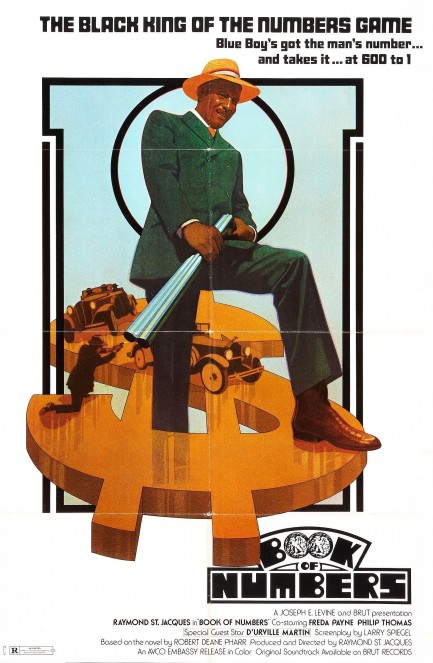

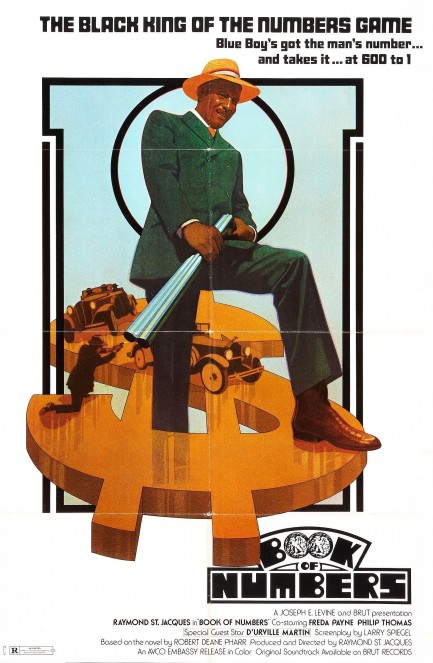

This poster was made for the crime drama Book of Numbers, which premiered in the U.S. today in 1973. The movie falls into the category of blaxploitation, but it's also an ambitious period piece, with a Depression era focus, a deep subtext, and a determination to portray a type of black American life rarely seen onscreen. During the lean years of 1930s a couple of waiters who harbor big dreams ditch food service and hatch a scheme to set up a numbers racket. They roll into El Dorado, Arkansas, get some local help, and soon are making cash faster than they know how to spend it. Their success inevitably attracts the attention of the law, organized crime, and the local Ku Klux Klan. Can the protagonists succeed against all these foes? And what does success look like for black men in the 1930s? No matter how much money they make, they are still not respected, safe, or free.

The movie stars future Miami Vice stud Philip Michael Thomas, along with Raymond St. Jacques, who produced and directed. Their two characters are decades apart in age, and vastly different in how they deal with constant racism. Thomas takes no guff from anyone, even when it costs him; St. Jacques will play any role expected of him by whites in order to survive. This doesn't sit well with the hot-headed Thomas, and leads to growing resentment. In our view, this is the most unique aspect of the film. It implies that because society forces black men to play roles, they can never be truly known by anyone outside their intimate circle. Robert Deane Pharr wrote the source material for this, and it must be an interesting novel, because it spawned a good movie. Book of Numbers is tough, adult, thought-provoking, and historically revealing. We recommend it for 1930s buffs, blaxploitation aficionados, and of course fans of Miami Vice.

Miami, Florida: sunny weather, shady people.

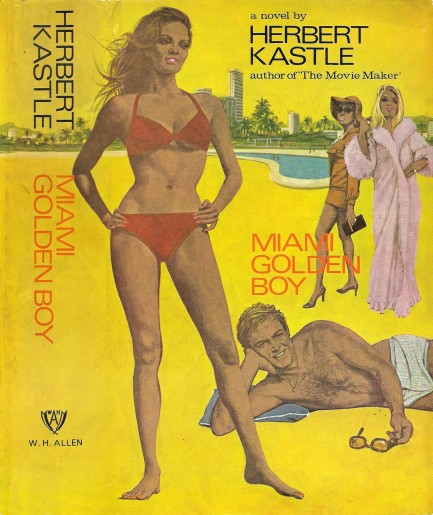

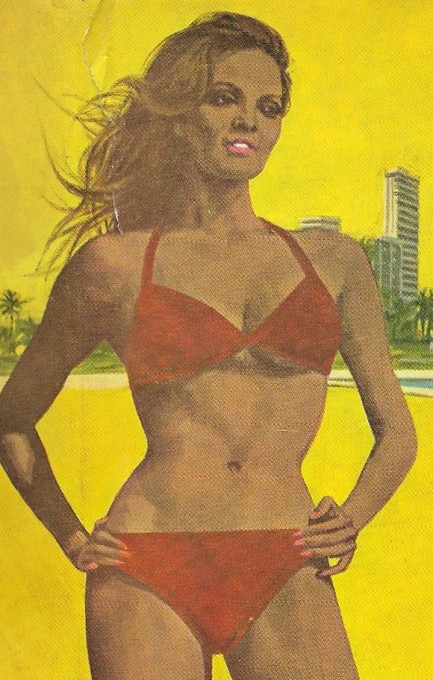

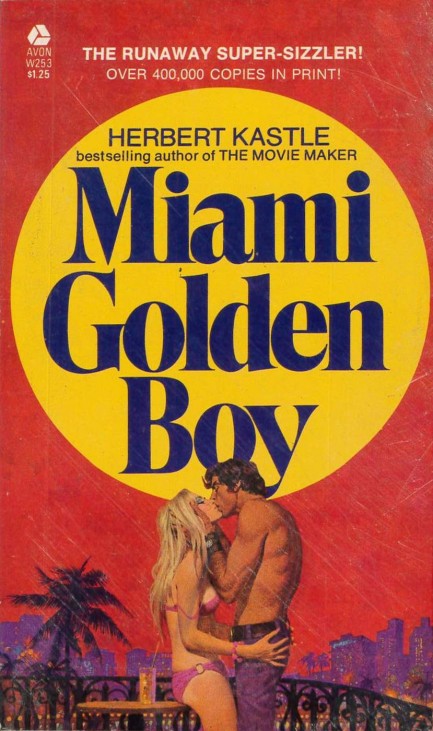

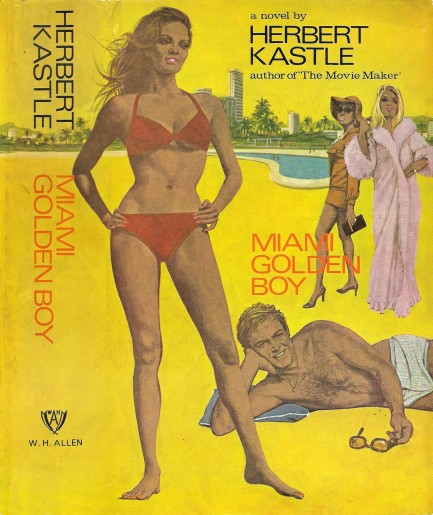

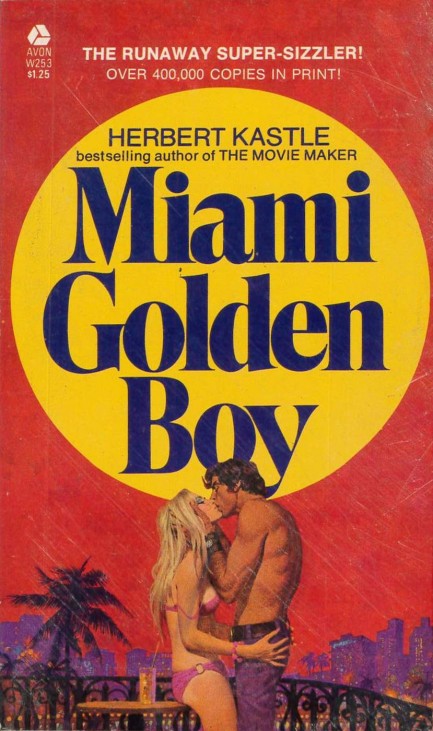

We shared a cover for and talked about Herbert Kastle's 1970 thriller Miami Golden Boy back at the beginning of this year. Above you see the 1971 paperback edition from Avon. We could have bought this version, but we were too taken by the hardback's Barbara Walton sleeve art. The effort above, on the other hand, is uncredited, which is always a shame. Miami Golden Boy was good, if a bit forced (the main character's last name is Golden, to give you an idea how Kastle thinks), but the execution is at a high level. You can read more about the book here.

A jazz legend shows her stripes.

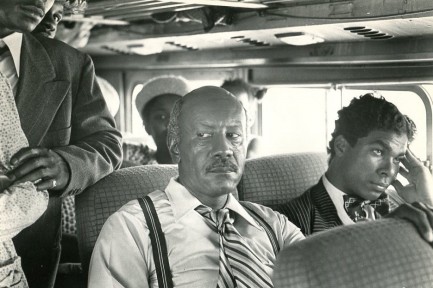

Above you see a live concert photo of musical pioneer Jo Thompson, who broke segregation barriers as a jazz performer, particularly in Miami, where she played often and where this image was made by famed photographer Bunny Yeager. Thompson also performed in Detroit, where she was based, New York City, Havana, London, Paris, and other European hotspots. She isn't well known today but she's considered by jazz lovers to have helped pave the way for black performers who came along slightly later, and critic Herb Boyd said about her that she was, “a consummate storyteller whether standing or at the keyboard."

That being the case, we'll highlight a story Thompson occasionally told about Frank Sinatra, the hipster gadabout of the mid-century, who came to see her one night at the Cork Club in Miami. He was with Ava Gardner, and after the show invited Thompson to join them at their table. The Cork, being in the deep south, didn't allow black performers to sit at the tables, let alone with white companions. But Sinatra being Sinatra, the rule crumbled, at least for the night. Thompson greatly appreciated that. And the jazz world appreciated her. She was a trailblazer. She lived a very long time, long enough to receive many overdue tributes, before finally dying just two years ago of COVID-19. That being the case, we'll highlight a story Thompson occasionally told about Frank Sinatra, the hipster gadabout of the mid-century, who came to see her one night at the Cork Club in Miami. He was with Ava Gardner, and after the show invited Thompson to join them at their table. The Cork, being in the deep south, didn't allow black performers to sit at the tables, let alone with white companions. But Sinatra being Sinatra, the rule crumbled, at least for the night. Thompson greatly appreciated that. And the jazz world appreciated her. She was a trailblazer. She lived a very long time, long enough to receive many overdue tributes, before finally dying just two years ago of COVID-19.

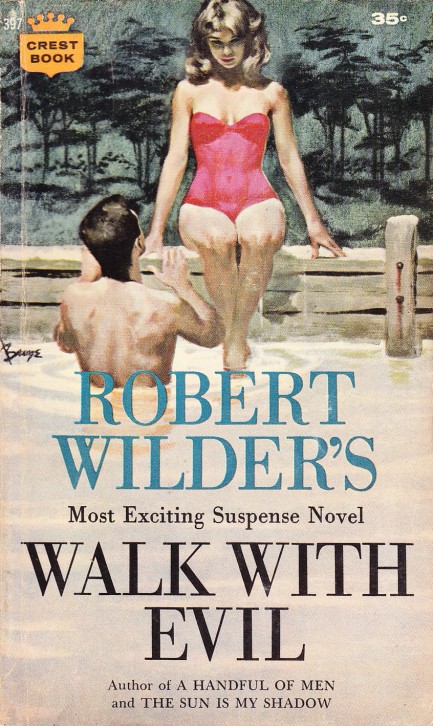

But I don't want to swim with you. Walking with you was already enough of an ordeal.

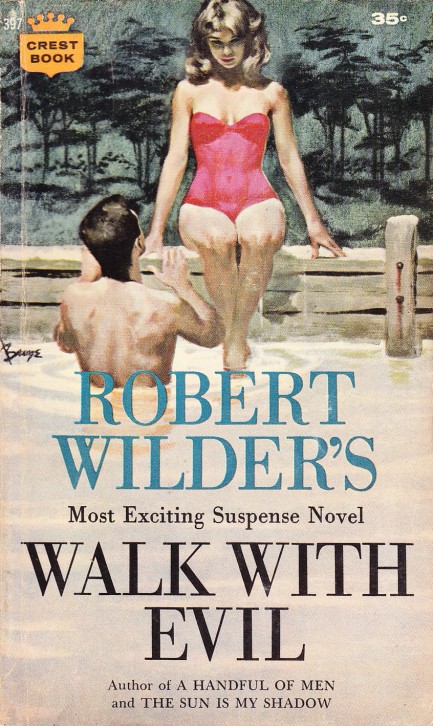

The front of Robert Wilder's Walk with Evil calls it the author's most exciting suspense novel. We wouldn't know, because we've read only this one, but it's good. The dispersed narrative follows a reporter who vacations in the environs of Palm Beach and stumbles upon one of the most famous missing persons in recent history—a federal judge who vanished without a trace years ago. Meanwhile, a recently paroled crime kingpin is cruising the Florida coast in a yacht. The missing-now-found judge and the kingpin are connected. The former once presided over the trial that sent the latter to prison.

Wilder's tale skips around between the kingpin and his henchmen, the judge and his daughter, the reporter, and an insurance investigator also poking around. We soon learn that the kingpin is searching for a million robbery dollars that are hidden somewhere along the coast, and that the judge may hold the key. The plot threads which inexorably twist into a knot of tension and danger are very competently managed by Wilder. The only weakness—as usual with these vintage thrillers—is the love story, which once again is perfunctory, with the woman given no concrete reason to fall for the hero other than that he's there.

But it's a minor issue. The story works, and the characters are interesting and diverse. We'll never know if Walk with Evil is really Wilder's most exciting novel unless we try a couple more, so maybe we'll do that, assuming we can find some with reasonable price tags. The cover art on this was painted by Barye Phillips—yes, again. The man was simply among the most ubiquitous illustrators of his era. The copyright is listed online as 1958, however ours says clear as day on the inside that the original publication year was 1957, with this Crest edition arriving in 1960.

Disaster looms if she moves even a millimeter.

Not only is Monica Bannister precariously positioned on her pedestal, but her gown is precariously positioned on her body. One wobble and she'll end up on the floor showing plenty more than planned, but it just so happens she's too graceful for that because her show business career was based on coordination. As dancer and actress she appeared in more than thirty films, including 1933's Mystery at the Wax Museum, 1941's Moon over Miami, and 1945's The Picture of Dorian Gray. All her film appearances save two were uncredited, but she went on to open a dance school and teach others how to be graceful too. This photo came out of the studio of famed lensman Murray Korman, who photographed thousands of famous and would-be famous people from the 1920s into the 1950s. There's no exact date on this, but it's from the mid-1930s.

Herbert Kastle writes South Beach as Sodom in his sprawling kidnap thriller.

Miami Golden Boy is the wrong title for this book. It's too trite for the tale of a plot to kidnap the invalid former president of the U.S., which intersects a plot by Havana expats to return to Cuba and depose Fidel Castro. While the book gets its name from the ostensible central figure Bruce Golden, there's a vast assortment of characters, including a Kennedyesque political clan, that keeps him out of the narrative for entire chapters. These characters have deeply detailed personal lives that add dimension but strain credulity. One secretly has cancer, one is secretly gay, one is secretly sadistic, one is secretly a pedophile, one is being blackmailed, one is secretly a drug addict, one is secretly suicidal. It's a lot. But okay, the only question that matters is does it all work? Well, mostly. Kastle uses these secrets to weave a tale of decadent American decline, with South Beach as a backdrop. A choice example:

“The country is beginning to stink. Our stated goals and our actual goals are drawing farther and farther apart. And the divergence is tearing us apart. We've either got to bring the actual goals closer to the stated goals—reduce the materialism in our lives, the idiocy of our anti-communist crusades, the cruelty and blindness of our dealings with blacks—or admit that the stated goals are false.”

Kastle wrote that fifty-two years ago, and we know how things have gone since then. His abduction plot is a symptom of the greed, hypocrisy, and decline he details. The scheme involves several characters using several other characters as pawns. The lever in most cases is sex, and the book is pretty well packed with sexual content, occasionally explicit, and in one case violent. Then there's that pedo thing too. Kastle doesn't shy away from it, though you may wish he had. The tapestry of duplicity and manipulation, in terms of how it relates to the kidnap, needs to weave together in perfect synchronization, and of course doesn't. The scheme blows up spectacularly. If it didn't there'd be no book. Conversely, Kastle brings everyone's secret stories to miraculous conclusions within the space of the final thirty pages. That's the drawback of so many characters—a few story arcs don't end convincingly.

Even so, the one thing you cannot say is that Kastle doesn't know how to write. His skillful prose makes the slam bang climax almost believable. Bruce Golden, a bit of a shallow playboy, isn't a great guy but at least he isn't a killer, kidnapper, or political plotter, so he's the character you root for. His love interest Ellie De Wyant, on the other hand, is a crucial if unwitting cog in the kidnapping, which means if Golden is to have her he may have to do something he's never done in his entire life—show courage in the face of danger. Will he or won't he? We think Miami Golden Boy is worth a read to find the answer. And speaking of worth, books with Barbara Walton cover art aren't usually cheap, but this one from the publisher W.H. Allen was. We got lucky. Walton was one of the top illustrators of her era. See more from her here and here.

Packed with flavor and fortified with the recommended daily allotment of vitamin f.

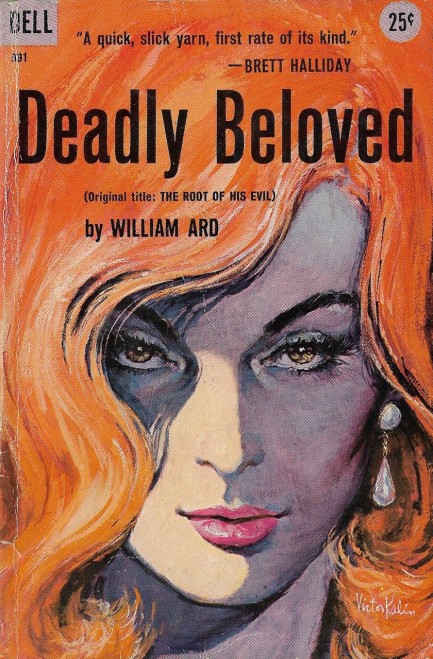

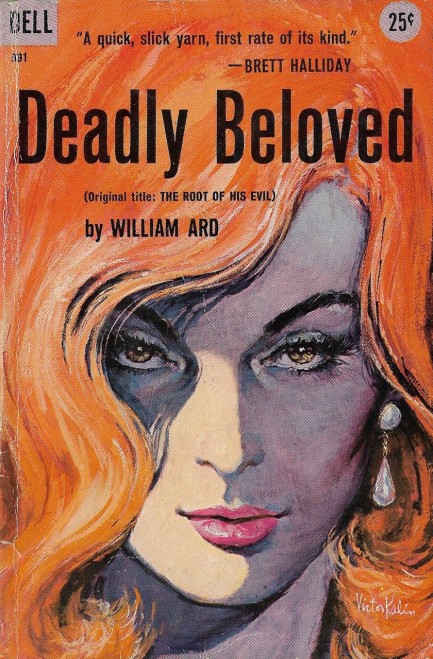

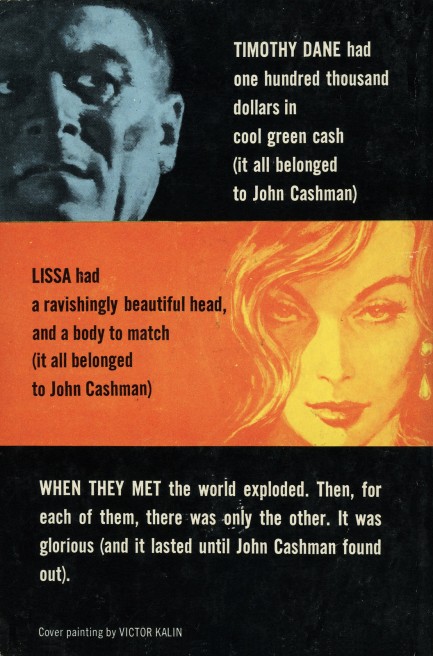

Victor Kalin went the tight focus route with this cover of an orange femme fatale he painted for William Ard's 1958 thriller Deadly Beloved, also published as The Root of His Evil. We love the art, and we loved the book too. An insurance investigator named Tim Dane is hired to transport a $100,000 gambling debt from an unlucky loser to a Miami hood named John Cashman. Cashman plans to use the money to help finance a war in Latin America, but that's just background. The more immediate part of the narrative involves an exotic dancer named Lissa, real name Elizabeth Ann Miller, who he has ringfenced with the help of 24/7 bodyguards and a lifetime management contract. Dane ignores warnings to keep away and is soon giving Lissa deep nocturnal lovin'—a pleasure that could cost his life if Cashman finds out about it. Ard, who also wrote as Ben Kerr, Mike Moran, et al, is a talented stylist with an approach all his own. His way of cutting transitional exposition is pretty neat. Every writer is required to do it, but Ard can cross town within the space of a sentence and still not sound like he's rushing. We're already trawling the auction sites for more from him. Highly entertaining.  Edit: We got an e-mail asking exactly what we meant by "cutting transitional exposition." We don't want to search through the book for an example, so we'll make up one. It would go something like this. "He decided he'd have to drive to Coral Gables to ask Cashman in person, and two days later when the door opened to his knock, he was surprised that it wasn't a servant but Cashman himself who answered."

Sometimes you have to look at things from a whole new angle.

How many mid-century actresses began as Playboy models? An absolute raft of them. The 1957 photo above shows Dolores Donlon, who was the magazine's centerfold in August of that year. Donlon was an unusual case. She had been toiling in Hollywood since 1944, landing minor film roles and scattered magazine covers. She managed to earn seventh billing in 1954's The Long Wait, and third in 1957's Flight to Hong Kong, but they weren't major films. When she finally posed nude it was much later than usual—she was thirty-seven. It's hard to determine whether the new tactic directly paid off, but from that point forward she became a well established television actress, racking up more than twenty-five credits on shows such as 77 Sunset Strip and Miami Undercover. It wasn't movie stardom, but it was success. Was it Playboy that made the difference? Probably only she and her agent knew, and neither of them are around to tell us.

|

|

The headlines that mattered yesteryear.

2003—Hope Dies

Film legend Bob Hope dies of pneumonia two months after celebrating his 100th birthday. 1945—Churchill Given the Sack

In spite of admiring Winston Churchill as a great wartime leader, Britons elect

Clement Attlee the nation's new prime minister in a sweeping victory for the Labour Party over the Conservatives. 1952—Evita Peron Dies

Eva Duarte de Peron, aka Evita, wife of the president of the Argentine Republic, dies from cancer at age 33. Evita had brought the working classes into a position of political power never witnessed before, but was hated by the nation's powerful military class. She is lain to rest in Milan, Italy in a secret grave under a nun's name, but is eventually returned to Argentina for reburial beside her husband in 1974. 1943—Mussolini Calls It Quits

Italian dictator Benito Mussolini steps down as head of the armed forces and the government. It soon becomes clear that Il Duce did not relinquish power voluntarily, but was forced to resign after former Fascist colleagues turned against him. He is later installed by Germany as leader of the Italian Social Republic in the north of the country, but is killed by partisans in 1945.

|

|

|

It's easy. We have an uploader that makes it a snap. Use it to submit your art, text, header, and subhead. Your post can be funny, serious, or anything in between, as long as it's vintage pulp. You'll get a byline and experience the fleeting pride of free authorship. We'll edit your post for typos, but the rest is up to you. Click here to give us your best shot.

|

|

That being the case, we'll highlight a story Thompson occasionally told about Frank Sinatra, the hipster gadabout of the mid-century, who came to see her one night at the Cork Club in Miami. He was with Ava Gardner, and after the show invited Thompson to join them at their table. The Cork, being in the deep south, didn't allow black performers to sit at the tables, let alone with white companions. But Sinatra being Sinatra, the rule crumbled, at least for the night. Thompson greatly appreciated that. And the jazz world appreciated her. She was a trailblazer. She lived a very long time, long enough to receive many overdue tributes, before finally dying just two years ago of COVID-19.

That being the case, we'll highlight a story Thompson occasionally told about Frank Sinatra, the hipster gadabout of the mid-century, who came to see her one night at the Cork Club in Miami. He was with Ava Gardner, and after the show invited Thompson to join them at their table. The Cork, being in the deep south, didn't allow black performers to sit at the tables, let alone with white companions. But Sinatra being Sinatra, the rule crumbled, at least for the night. Thompson greatly appreciated that. And the jazz world appreciated her. She was a trailblazer. She lived a very long time, long enough to receive many overdue tributes, before finally dying just two years ago of COVID-19.