Whoever ends up with the most loses.

This Paramount promo image shows Carole Lombard and was made for her 1933 horror drama Supernatural, which was part of a small set of vintage movies concerned with spiritualists and the supposed netherworld. Movies we've discussed that feature (always fake) séances or seers include Bunco Squad, The Amazing Mr. X, Nightmare Alley, and Ministry of Fear. In a career spanning more than seventy films, Supernatural was Lombard's only fright flick. Its rarity requires that we give it a watch, which we'll do pretty soon.

Well, you're right. I'm mainly angry at myself. But I'm going to take it out on you.

Pre-Code star Clara Bow looks mighty miffed in this promo shot made for her 1928 Paramount drama Ladies of the Mob, in which she plays the daughter of a lifelong criminal who falls in love with a crook and tries to reform him. Interesting trivia: because bullet squibs wouldn't be invented until around 1943, for shooting scenes studios often employed marksmen to fire real bullets near actors. Both Bow and her co-star Richard Arlen were injured by ricocheting fragments. Which brings us back to the photo. We like to imagine Bow facing Paramount head honcho Jesse Lasky and saying, “Don't worry, Jesse—I'm just going to shoot near you.”

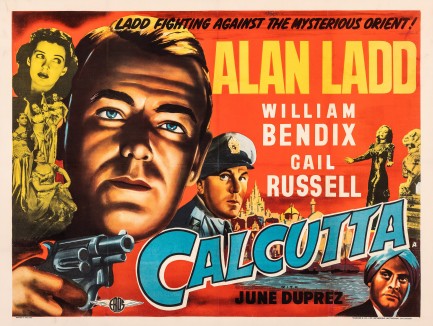

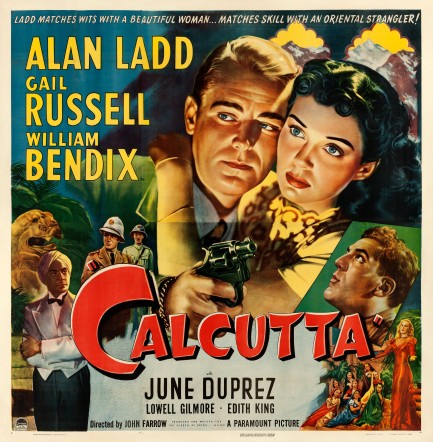

Calcutta is heavy on looks but light on substance.

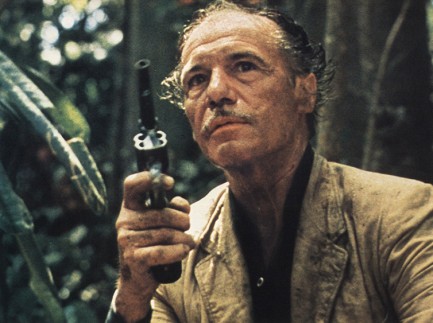

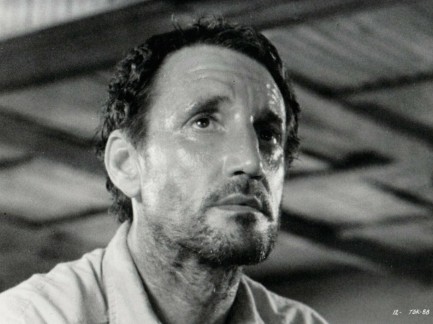

We'll tell you right out that Calcutta came very close to being an excellent movie, but doesn't quite get over the hump. It deals with a trio of pilots flying cargo between India and China on fictional China International Airways. The trio, Alan Ladd, William Bendix, and John Whitney, stumble upon a highly profitable international smuggling ring and quickly find that the villains play for keeps. Along with the fliers, the film has Gail Russell as Whitney's girlfriend, and June Duprez as a slinky nightclub singer. While the exotic setting marks the film as an adventure, it also fits the brief as a film noir, particularly in Ladd's cynical and icy protagonist.

As we said, the movie isn't as good as it should be, but there are some positives. Foremost among them is Edith King as a wealthy jewel merchant. She smokes a fat cigar, the masculine affectation an unspoken but clear hint of her possible lesbianism, and with a sort of jocular grandiosity simply nails her part. Another big plus is the fact that the miniature work (used in airport scenes), elaborate sets and props, and costumed extras all make for a convincing Indian illusion—definitely needed when a movie is filmed entirely in California and Arizona (Yuma City and Tucson sometimes served as stand-ins for exotic Asian cities, for example Damascus in Humphrey Bogart's Sirocco).

On the negative side, Calcutta has two narrative problems: the head villain is immediately guessable; and Russell is asked to take on more than she can handle as an actress, particularly as the movie nears its climax. Another problem for some viewers, but not all, is that the movie has the usual issues of white-centered stories set in Asia (or Africa). However, within the fictional milieu the characters themselves seem pretty much color and culture blind, which isn't always the case with old films. Even so, the phalanxes of loyal Indian servants, and the dismissiveness with which they're treated—though that treatment is historically accurate—probably won't sit well with a portion of viewers.

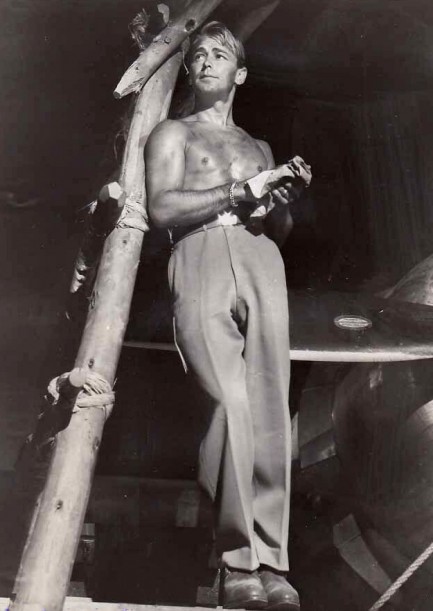

Here's what to focus on: Alan Ladd. He's a great screen presence, a solid actor in the tight-lipped way you often see in period crime films, and the filmmakers were even smart enough to keep him shirtless and oiled for one scene. We swear we heard eight-decade-old sighs on the wind, or maybe that was the Pulp Intl. girlfriends. They'd never seen Ladd before, but immediately became interested in his other films. We were forced to tell them he was a shrimpy 5' 6” and they were a bit bummed. But he had it—and that's what counted. His it makes all his films watchable, but doesn't quite make this one a high ranker. Calcutta had its official world premiere in London today in 1946.

Texas legislature finally stops with the half measures and passes law that stamps out all rights for women.

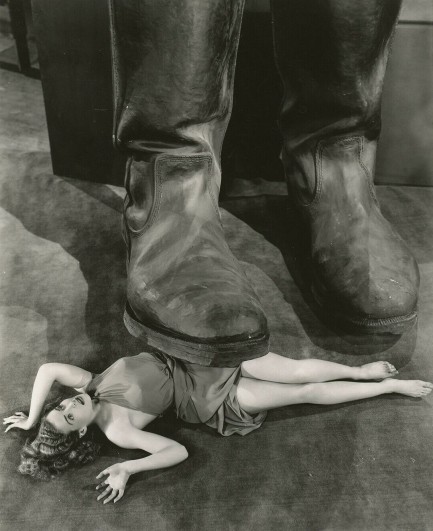

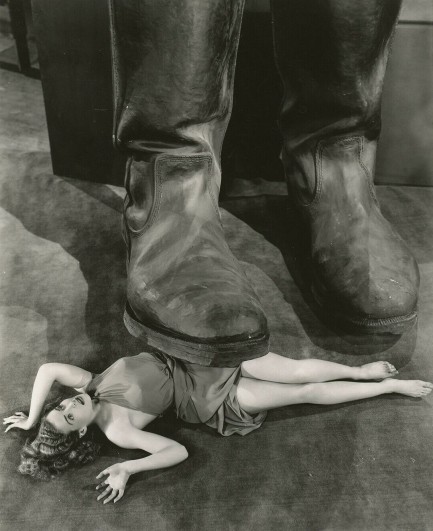

Above: a Paramount Pictures promo image of Janice Logan about to be smashed by a boot much larger than her. It was made for her 1940 sci-fi flick Dr. Cyclops, which deals not with a big man as you might expect, but with a normal sized man who makes those around him tiny. Science fiction movies from the period tend to be a bit silly and this one is no exception, but an efx team probably spent weeks making those boots, so you gotta respect the effort.

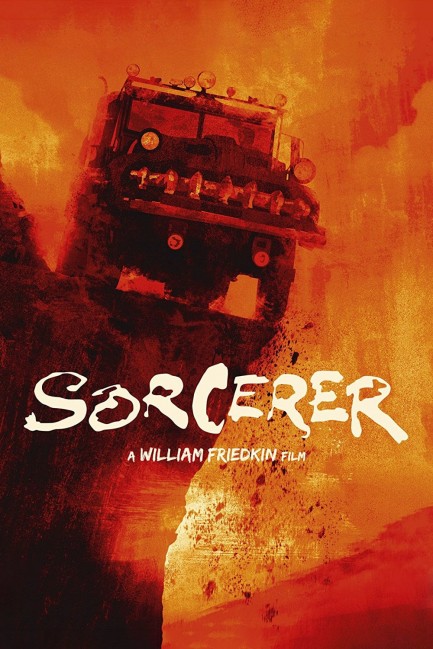

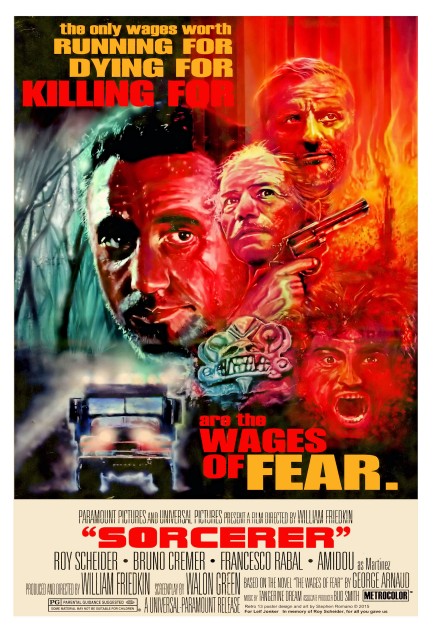

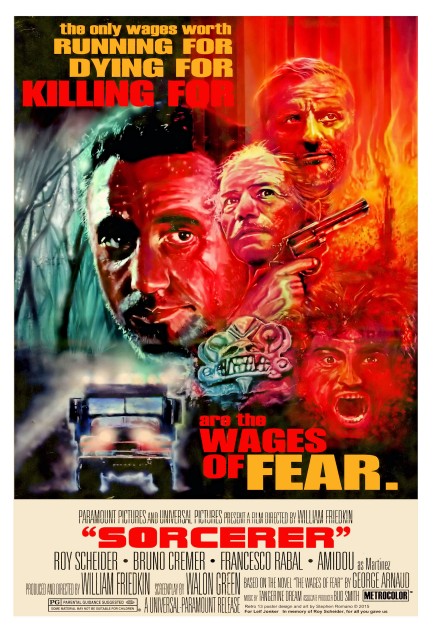

This Sorcerer performs some scary tricks.

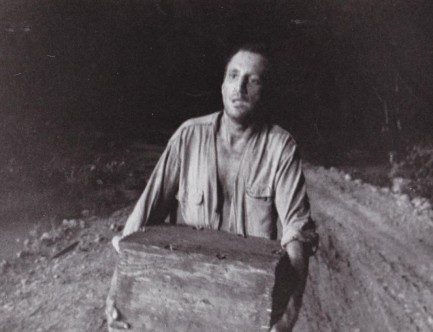

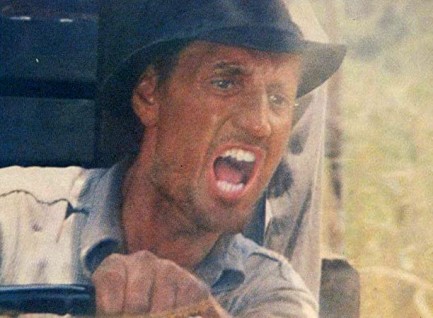

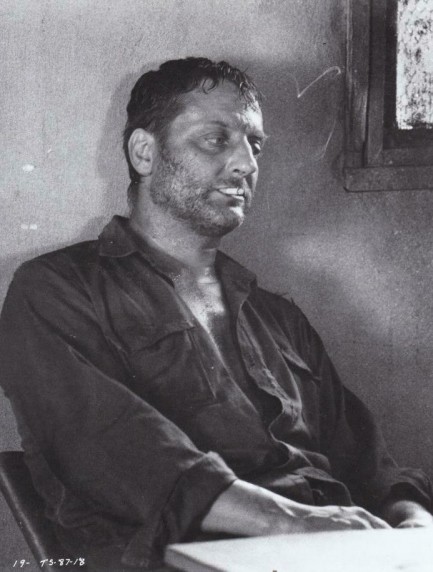

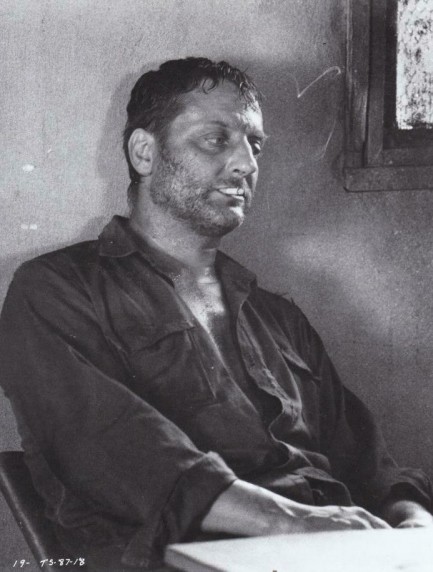

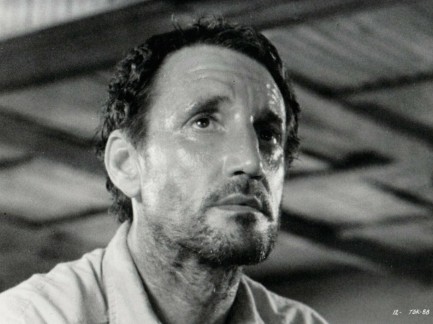

The dark action drama Sorcerer, for which you see a promo poster above, is one of those movies that didn't do well when it was released, but has been reevaluated a bit in recent years. We watched it last night and came away impressed. One of the main criticisms of this movie was that it was too long and too focused on backstory, but in this new era of streamed entertainment, considerations such as running times have gone out the window. You've noticed that, right? How much longer movies have gotten now that they're consumed in the home? Netflix and the other streaming services apparently figure you aren't going to watch the film without stopping it several times anyway, so why fret about their length. And certainly this is one of the enticements for modern directors working with streaming services. No butchery by studios obsessed with running time. Less interference. In such a milieu, Sorcerer isn't overly long, or overly detailed. Some of its weaknesses have become strengths.

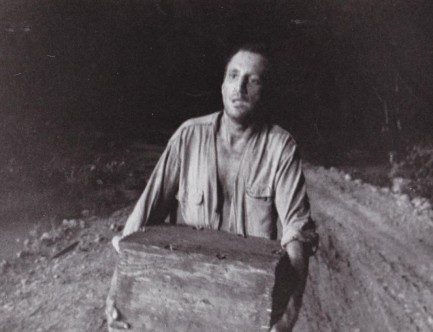

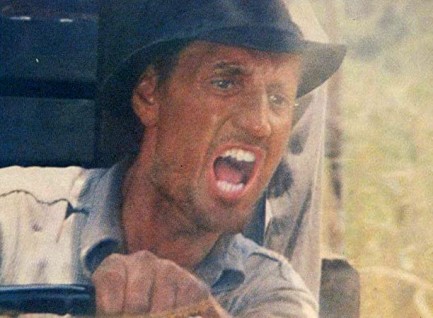

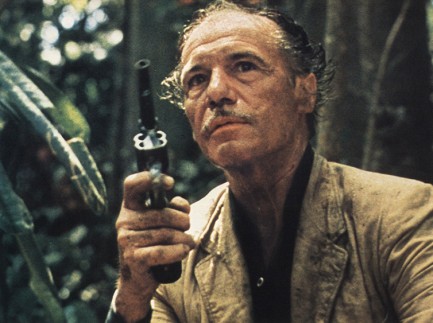

The story is actually pretty simple, despite all the hand-wringing over its length and structure. Four shady crooks in a Latin American town called La Piedra are chosen to drive two trucks of nitroglycerine days through treacherous jungle so the explosives can be used to extinguish a raging oil well fire. The oil company is desperate, and so are the men. Though the explosives are cushioned in beds of sawdust, one serious bump and these guys will be raining down in pieces. They're four hard luck men stuck in a hellhole, and even though the trip has low survivability, they'll do anything for a chance at a new start in life. But the characters' Conradian journey from La Piedra into pure madness comes later. The movie first tells how each man came to be in circumstances where getting out of town is worth risking their lives. Each of their stories is bizarre and violent. We suspect this bothered viewers. It makes the teaming up of the group seem unrealistically coincidental, but it's a simple structural artifice. There's no coincidence. Any four men chosen to drive the trucks would have crazy histories.

Sorcerer also tells in detail how that oil well became an inferno, again throwing viewers. They probably asked why such details were needed. But they are needed. The movie is based on Georges Arnaud's novel Le salaire de la peur, aka The Wages of Fear, a capitalist  critique about how the impoverished will take deadly chances for a little cash, and how corporations take advantage of that desperation without concern or empathy, particularly when the balance sheet slips into the red. The backstory of the oil company is important to the narrative. critique about how the impoverished will take deadly chances for a little cash, and how corporations take advantage of that desperation without concern or empathy, particularly when the balance sheet slips into the red. The backstory of the oil company is important to the narrative.

Yet another reason the movie was poorly received is the title. Director William Friedkin had previously scored a global hit with The Exorcist. A title like Sorcerer sounds supernatural, but it's actually the name of one of the trucks the characters drive. Universal Pictures and Paramount Pictures, which both backed the film, didn't do much to counter mistaken impressions. They thought they had a dud on their hands so they promoted the movie in a way that made it seem eerie to take advantage of Friedkin's reputation. Many filmgoers walked away feeling cheated, and many reviewers too, we suspect. If the internet had existed back then maybe filmgoers would have known Sorcerer was based on a novel, as well as on a French adaptation from 1953.

But setting all that aside, this much is true of Sorcerer: it's visceral in a way few 2021 films could hope to be. In the past, quantum leaps in filmmaking always came about as ways of making a more realistic product. Sound, color, camera advances, stunts, and more, all worked toward that end. Then came computerized effects. Those were different. They were designed to make the unrealistic possible, to help portray realms and worlds that didn't exist. But the same CGI that helped to portray the fantastic flowed backward into more prosaic areas of filmmaking, not because it looked better, but because it was cheaper. Smoke and fire are CGI now, even in simple dramas, and blood splatters are computerized. Nearly all explosions all fake today. None of these mundane uses of CGI are improvements over practical effects. They're just cheaper, and they look it. So while CGI is fine for sci-fi and superhero movies, using it in crime dramas when a gangster gets shot or a car explodes is a step backward for cinematic art. As far as we know, over the course of more than a century of filmmaking, CGI is the first technical advance that makes movies look less realistic.

Sorcerer is specifically a reminder of what practical effects can do. There's real jungle, real fire, and real explosions. Blasts shake the ground, and not through digital cam effects, but through physical concussion. Virtually every frame of Sorcerer makes a mockery of modern filmcraft, both in terms of technical values and actorly commitment. Headliner Roy Scheider and his co-stars went through real discomfort to spin this tale. They're covered in real sweat, real dirt. That terrible town of La Piedra they're stuck in is a master class in gritty set design. It looks a lot like some actual purgatories we ventured through the years we were living in Guatemala, where Arnaud's novel is set. It reminds us particularly of a town we wandered into just as a crowd had finished beating a man to death. But that's another story. If you watch Sorcerer for no other reason, watch it to see what films looked like when reality was the utmost goal, rather than slick economy. But us? We'll watch it again because it's great. Sorcerer premiered in the U.S. today in 1977.

That is not a smile of happiness. That's a smile of insanity.

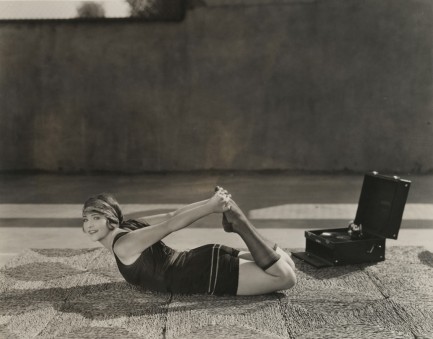

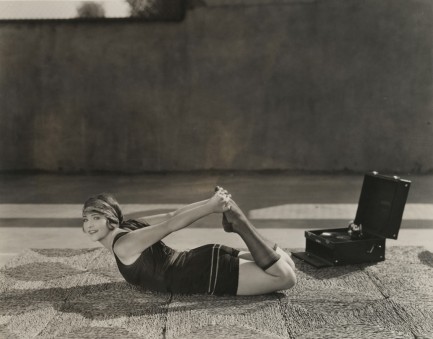

Compson curls up with some good music.

U.S. actress Betty Compson pulls off an uncomfortable looking pose and does it with a winning smile in this Paramount Pictures promo photo from sometime in the 1920s. This is a standard yoga position called Dhanurasana, or the bow, though we doubt yoga was known at all in the U.S. during the ’20s. Instead the text on the rear of the photo describes what Compson is doing this way:

How To Keep Fit. Leg, arm, back and shoulder muscles are developed by this exercise, as demonstrated by Betty Compson. Lie flat on the floor out-stretched. Simultaneously bend the knees and fling the hands back until they can grip the feet. This exercise is more beneficial—likewise more difficult—if executed slowly.

To which we say, no damn way we're trying that.

Anyway, Compson was a major star, appearing in more than one hundred films and shorts, both silent and with sound, between 1914 and 1948. Her highlight was 1928's The Barker, which earned her an Academy Award nomination for Best Actress. We're giving her an award for this nice promo shot. We'll never do the exercise, but we love the image.

Sometimes you simply have to look.

You know you shouldn't look at them. You try to direct your gaze where it belongs—at the band, or at the Champagne pyramid, or maybe at the roasted baby pig platter. You see people staring and know if you do too they'll all catch you. But the effort of not looking becomes a Sisyphean task. Lateral gravity becomes your enemy. Your eyes keep getting puuuuulled in that direction and you keep stopping them, just barely, by firing the reverse thrusters full power. But then, after many slow mintues of this torture, you figure, well screw this, maybe one day the planet will be in lockdown and this opportunity won't even exist. So you decide to take a really good look, just one, to get it out of the way, because if you don't you'll be fighting it all night. Plus she wants them to be looked at. Clearly. So you look—and flash! Someone takes a photo and your glance is immortalized as the evil side-eye of all time.

That moment happened April 12, 1957, as Sophia Loren attended a glittering Paramount Pictures dinner where she was the guest of honor. It was held at Romanoff's in Beverly Hills, a chic and popular restaurant, and Mansfield—being Mansfield—arrived last and sucked up the oxygen in the room like a magnesium fire. Every camera in the joint was following her—and by extension Loren, because the seating chart had placed them adjacent. Loren was a big star, but stars sometimes get trapped in other stars' orbits. Loren and Mansfield got locked into the same space-time continuum, eyes moved to boobs, and the infamous photo was shot. The images of the encounter were all in black and white. What you see above is a colorization, a pretty nice one, except the retoucher didn't do their homework. Mansfield's dress was pink that night. She nearly always wore pink. It was her favorite color. Even her house was pink.

The colorization below gets the dress right, and this second angle shows just how much skin Mansfield was revealing, which gives a clearer indication why Loren had to look. Mansfield's nipples were coming out. They had fishhooked Loren's eyes. She couldn't not look. Not not doing something is an ethical conundrum we've discussed before, and it's baffled some of the greatest minds of all time. As you might imagine, Loren hates the shot. Sometimes fans ask her to autograph it and she says she always refuses. The dinner that night was intended to welcome her to Hollywood. Well, she was welcomed in more ways than one. Mansfield showed her a surefire method for playing the celebrity game, by always making a big entrance—even if it meant almost making a big exit from her dress.

All she needed was for someone to believe.

Paulette Goddard had more false starts to her career than most Hollywood legends. During the late 1920s and early-to-mid 1930s she worked—without making much impact—for Selznick International Pictures, George Fitzmaurice Productions, 20th Century Pictures, Hal Roach Studios, and both Goldwyn Pictures and Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. She turned some heads in Modern Times, co-starring with Charlie Chaplain, who was her boyfriend at the time, but her major break came with Paramount when she starred opposite Bob Hope in The Cat and The Canary. She never looked back, appearing in seventeen films in the next five years, and more than fifty over the course of her career. One of those was Northwest Mounted Police, which is where the above promo photo comes. It dates from 1940.

Getting Mary-ed was one of the most important decisions of her life.

Above you see a Paramount Pictures promo image of U.S. actress Mary Astor made around 1930. Astor is remembered by movie fans for her role in 1941's The Maltese Falcon, but she had been in film for more than twenty years by then. We often note show business name changes. Astor's real name was Lucile Langhanke. Would she have been as successful using that name? There's no way to know, but we doubt it. To us, Langhanke sounds like a cut of meat. Like something from the middle ages. Gimme a langhanke and an ale! And a roasted Maltese falcon too! Acting is hungry work! But instead she appropriated the family name of a strain of British royalty and her career took flight, so it seems Mary made the right choice.

Of course I know it isn't raining in here. But I can't take a chance on anything ruining this hair-do.

This is an unusually cool shot, we think. In addition to its compositional elements, the pattern on the dress and umbrella are the same. Fashionistas take note—that's how it's done. The star of the photo is U.S. actress Pamela Tiffin, née Pamela Wonso, who was noticed for her beauty—a producer spotted her having lunch in the Paramount Pictures studio commissary—but became an award nominated performer. We've featured her before, and you can see those images here. 1966 on this one.

|

|

The headlines that mattered yesteryear.

2003—Hope Dies

Film legend Bob Hope dies of pneumonia two months after celebrating his 100th birthday. 1945—Churchill Given the Sack

In spite of admiring Winston Churchill as a great wartime leader, Britons elect

Clement Attlee the nation's new prime minister in a sweeping victory for the Labour Party over the Conservatives. 1952—Evita Peron Dies

Eva Duarte de Peron, aka Evita, wife of the president of the Argentine Republic, dies from cancer at age 33. Evita had brought the working classes into a position of political power never witnessed before, but was hated by the nation's powerful military class. She is lain to rest in Milan, Italy in a secret grave under a nun's name, but is eventually returned to Argentina for reburial beside her husband in 1974. 1943—Mussolini Calls It Quits

Italian dictator Benito Mussolini steps down as head of the armed forces and the government. It soon becomes clear that Il Duce did not relinquish power voluntarily, but was forced to resign after former Fascist colleagues turned against him. He is later installed by Germany as leader of the Italian Social Republic in the north of the country, but is killed by partisans in 1945.

|

|

|

It's easy. We have an uploader that makes it a snap. Use it to submit your art, text, header, and subhead. Your post can be funny, serious, or anything in between, as long as it's vintage pulp. You'll get a byline and experience the fleeting pride of free authorship. We'll edit your post for typos, but the rest is up to you. Click here to give us your best shot.

|

|

critique about how the impoverished will take deadly chances for a little cash, and how corporations take advantage of that desperation without concern or empathy, particularly when the balance sheet slips into the red. The backstory of the oil company is important to the narrative.

critique about how the impoverished will take deadly chances for a little cash, and how corporations take advantage of that desperation without concern or empathy, particularly when the balance sheet slips into the red. The backstory of the oil company is important to the narrative.