Darlin', that what happens here stays here stuff is baloney. What happens next—I guarantee—will stay with you forever.

Above: uncredited sleaze cover work from Nite Time Books for Scott Rainey's 1964 alternative lifestyle romp Las Vegas Lesbian. The back says: She was a beautiful desirable woman in a gambling town loaded with women. But there was a difference. She wanted to destroy every man—and woman—who wouldn’t play the game her way! Our advice: play the game exactly as she wishes. It would be the only game in Vegas where both sides win.

My husband is clueless. He suspects I'm having an affair, but he thinks it's with a guy from his softball team.

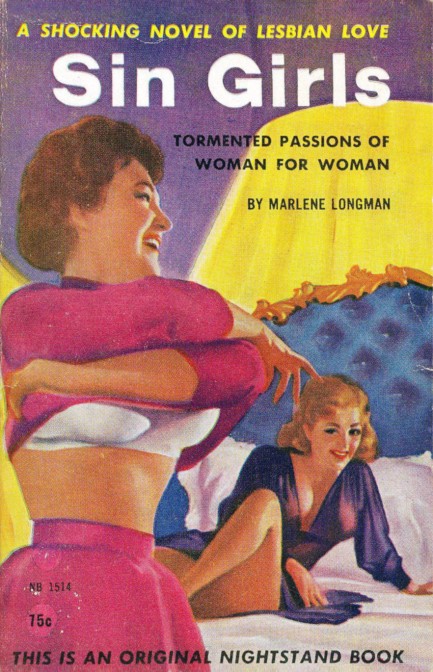

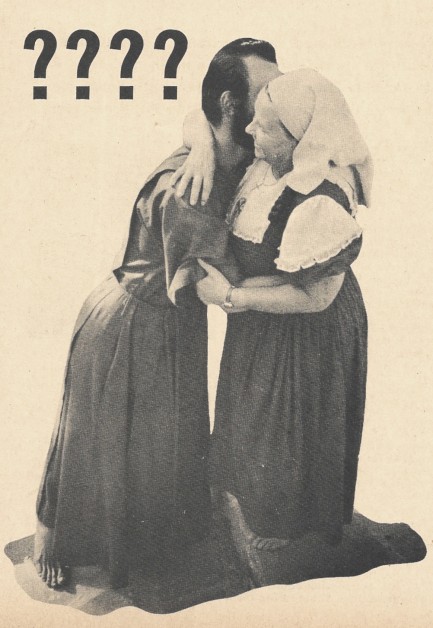

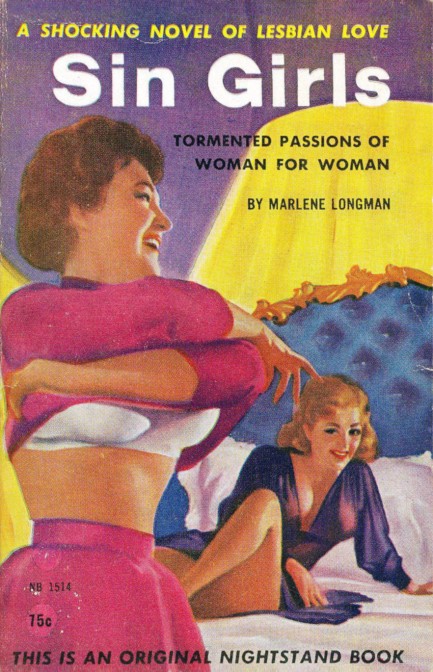

Above: a nice sleaze cover from Greenleaf Classics' Nightstand imprint for 1960's lesbian novel Sin Girls by Marlene Longman. This has the look of a photo-illustration, but it's credited to Harold W. McCauley.

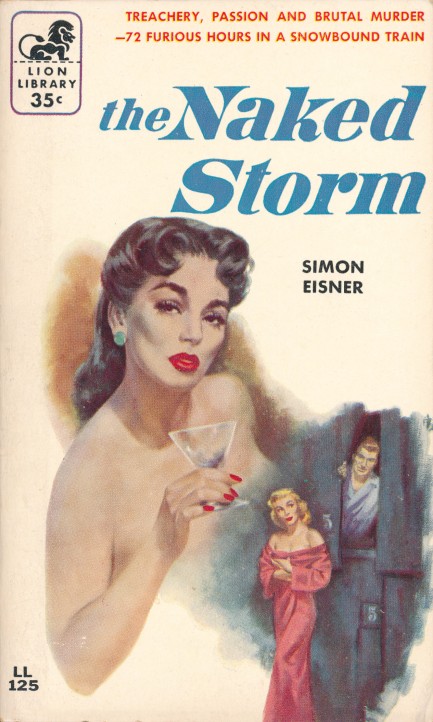

Cross-country train trip runs into heavy snow and cultural headwinds.

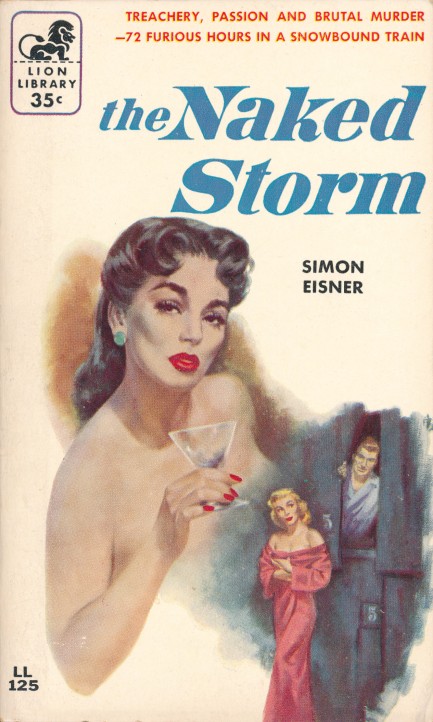

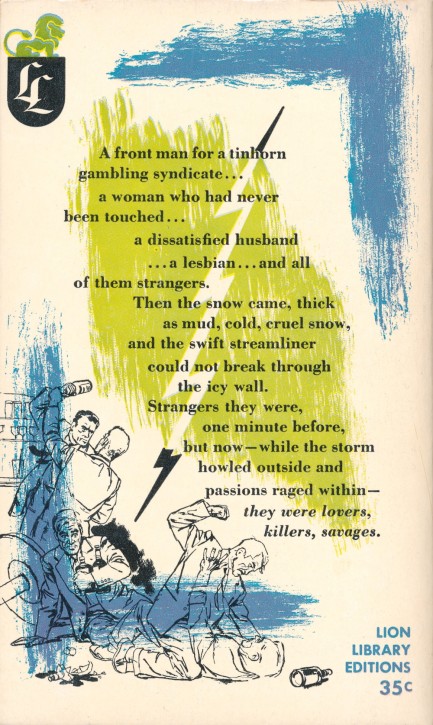

Falling into the category of well-known authors writing lurid fiction under pseudonyms, we have today The Naked Storm by Simon Eisner, from Lion Books in 1956 with a cover by Robert Stanley. Eisner was a cloak for sci-fi author C.M. Kornbluth, who was co-winner of the coveted Hugo Award in 1973 for his short story "The Meeting." The Naked Storm employs as its central plot device a train snowbound on the high Raton Pass during a bitterly cold Colorado winter. Essentially, it's a disaster novel, and you know we always grab those when we can.

This is not the only tale of this ilk Kornbluth was involved with. Perhaps you remember A Town Is Drowning. As is typical of trapped cast novels, a number of ongoing dramas take place here, and these offer windows into mid-1950s sociology. The character unwillingly controlled by organized crime figures, the pretty wife who's a heroin addict, the wide-eyed ingenue, the obese woman carrying a baby that will—shocked, we tell you!—turn out to be brown rather than white, and even the starving wolf that happens upon and begins eating a human body are interesting, but the notable personality here is the predatory lesbian who lacks a single scruple.

For that reason, the novel is an instructive look at the prevalent mid-century belief (which of course never went away in some benighted quarters) that homosexuality is a sickness. While any character can be a villain in fiction, and any character can be a sexual predator, since lesbianism is posited here to be both evil and contagious, the core drama of whether the ingenue will be lured onto track 69 is pure patriarchal hate-mongering. Hilariously, from an authorial point of view, she should choose one of the male characters with whom to bed down. The fact that they're all losers doesn't seem to matter.

So what you get in the end is a textbook example of homophobia in mid-century literature, one that's fit for study, should anyone out there be looking for thesis material. However, it's pretty well written and reasonably engrossing once you slog past the first thirty pages. Also, Kornbluth wrote other books with lgbt themes, such as Half and Sorority House, and because we haven't read them we feel it's only fair to suggest that he may have produced more nuanced, less reactionary work in those (though probably not). Hmm... to read a bigoted novel or not? Serious vintage book fans always face that question. You've been duly informed.

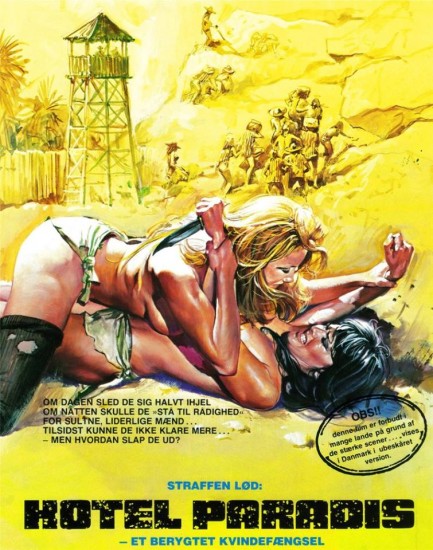

The lawless of the jungle.

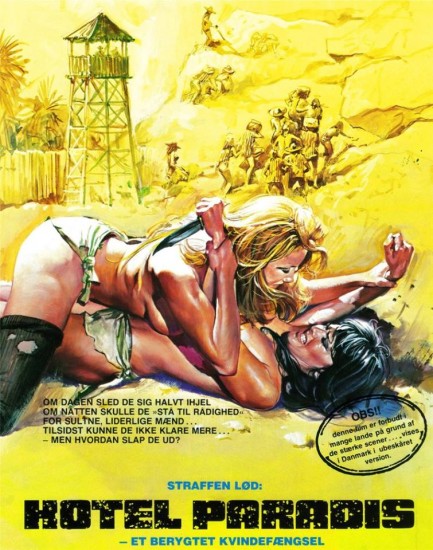

The curious and certainly never-to-reappear style of movies referred today as women-in-prison, or WIP, is a subgenre of sexploitation cinema that came about for one reason: it used settings in which women were helpless. Well, in theory. The dramatic thrust of the plots always derived from attempts to retain dignity and to escape captivity. The protagonist was usually an odd woman out—an unjustly imprisoned victim or an undercover operative—surrounded by a mix of prisoners who were hopeless, cruel, sexually predatory, and complicit, plus the abusive guards, one of whom nearly always was a sadistic woman.

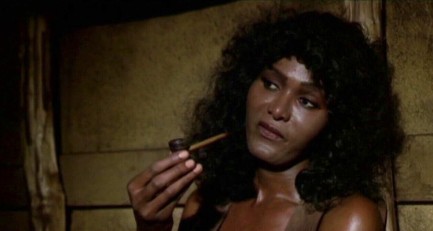

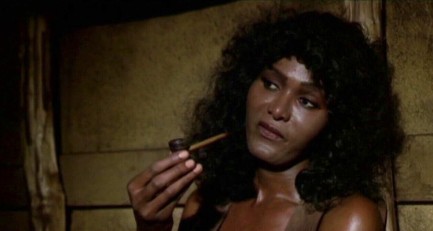

Hotel Paradis stars Anthony Steffen, Ajita Wilson, and the slinky Cristina Lay, sometimes referred to as Cristina Lai. There are numerous posters for it, but we like the above Danish effort featuring a fight to the death. Its text notes: This film is banned in many countries because of its strong scenes.... it's shown in Denmark in uncut version. Indeed. Interracial lesbian sex might be to blame for the banning. There are other possible reasons too. We won't waste our time trying to figure it out. As an aside, the movie was filmed concurrently with the WIP flick Femmine infernali using the same cast, director, and sets. So consider this a write-up of that movie too, since the pair are basically identical.

Plotwise, a group of women are being transported to a jungle hellhole prison where forced labor is used to dig for emeralds. When their guards are ambushed and killed by patriot soldiers seeking to steal the emeralds to fund a nebulous revolt, the women agree to continue posing  as prisoners in order to aid the infiltration of the camp. Behind bars is one inmate—Wilson—who has the shining or something, and keeps telling the others that violence, death, and freedom are coming. Also coming are WIP staples such as the evil wardenness, languorous shower scenes, whippings, baroque tortures, and sexual assault. It all ends pro forma with a climactic shootout. as prisoners in order to aid the infiltration of the camp. Behind bars is one inmate—Wilson—who has the shining or something, and keeps telling the others that violence, death, and freedom are coming. Also coming are WIP staples such as the evil wardenness, languorous shower scenes, whippings, baroque tortures, and sexual assault. It all ends pro forma with a climactic shootout.

Obviously, you have to go into these types of movies with a sense of humor if you can. When Lay first meets Wilson in the camp, she says, “My name's Maria. I'm frightened.” Why, oh why, didn't Wilson respond, “I'm Ajita. I'm a virgo”? Too bad we didn't write the script. Lay then helps herself to Wilson's pipe—which Wilson just a bit earlier had used to masturbate. If she can obtain a pipe you'd think she could get a dildo, but whatever, in prison you have to find your pleasures where you can. And in women-in-prison movies the same holds true—we thought the scene was hilarious. It was merely one of many.

It should be noted that while Wilson is the female lead, and we've shared a couple of racy images of her and highlighted her importance as a trans trailblazer, Lay is the audience draw here. She's unusually beautiful, and director Edoardo Mulargia and the movie's producers know it quite well. She gets the most loving camera work, the wettest shower scene, a nice interlude with Wilson, and goes through the entire final shootout obviously naked beneath her tattered prison tunic and with the top of it hanging wide open. It's not quite Frauen für Zellenblock 9, in which Karine Gambier and company perform their long escape sequence completely starkers, but it's notable just the same.

Hotel Paradis is obviously sexist and exploitative. As we've said before, in the same way blaxploitation movies usually show a racist power structure before the hero shatters it, sexploitation movies sometimes do the same with sexism. Sometimes. Not here. There are additional flaws. Compared to better WIP efforts it lacks the winking sense of humor, the empowerment undercurrent, and the sense of actors having fun while making something they know is ridiculous. There's a hardcore cut of this film with explicit scenes spliced in. It merely amplifies the aforementioned issues, so we suggest you avoid that version. But really, if you avoid Hotel Paradis entirely you'll probably be a better person for it. It premiered in Italy as Orinoco: Prigioniere del sesso in the autumn of 1980, and in Denmark today in 1983.

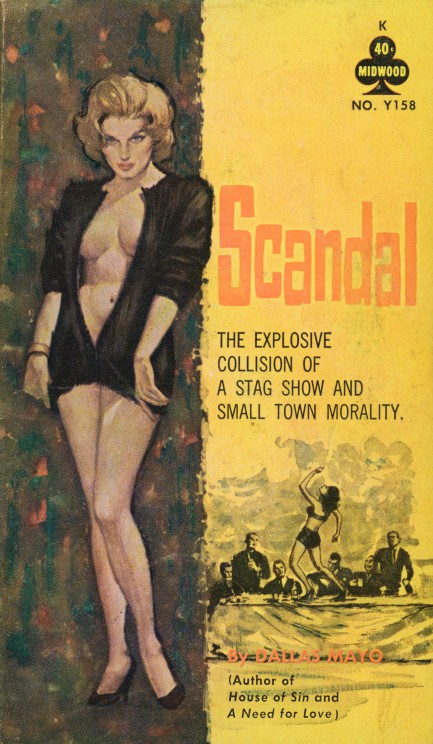

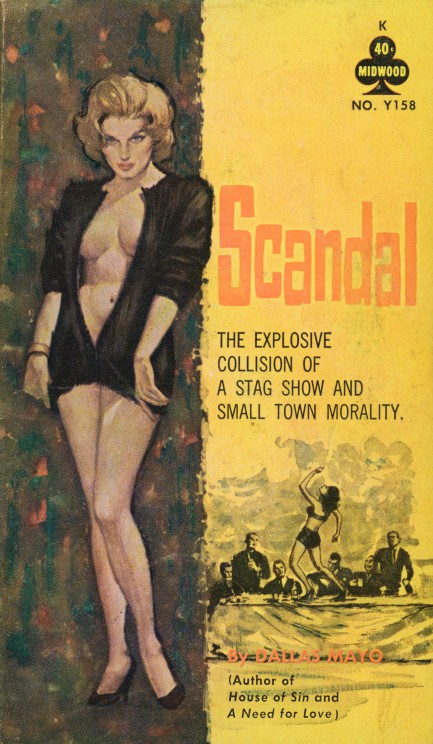

Sleaze with cheese and Mayo.

The 1962 Midwood Books sexploitation novel Scandal was written by Dallas Mayo, aka Gilbert Fox, and has uncredited cover art. Some of Midwood's offerings were tamer than others. Scandal falls on the mild side, with a story set in the fictive burg of Sedgemoor, where a set of local bros are about to throw a big stag party around the same time a Hollywood producer rolls anonymously through scouting for a possible movie location. The tale is told round robin style, with a name mentioned at the end of each chapter preceding the next chapter told from that person's point of view. In this way Mayo keeps cycling through about eight characters. By the end, the Hollywood producer loves one of the stag party strippers, another stripper finds lesbian love, a married couple rekindle their sex life, and so forth. It's cheesy stuff, but Scandal is interesting for the social attitudes on display, even it isn't very hot. Get extra Mayo here.

There's no better place to try something new.

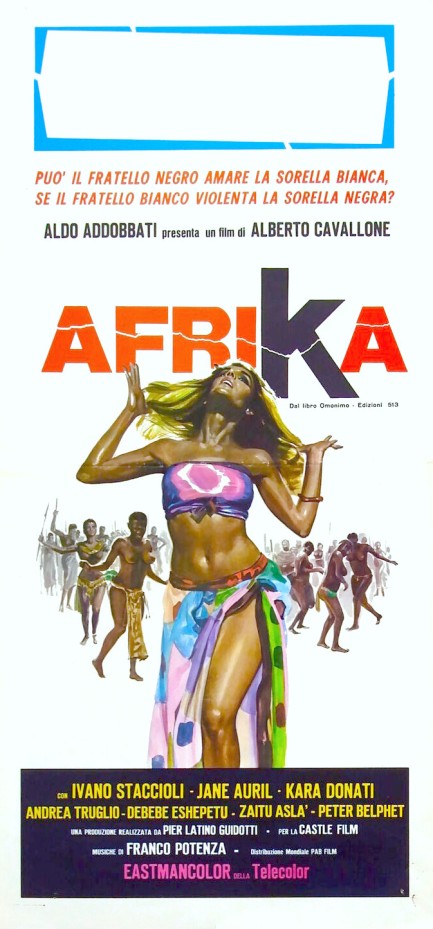

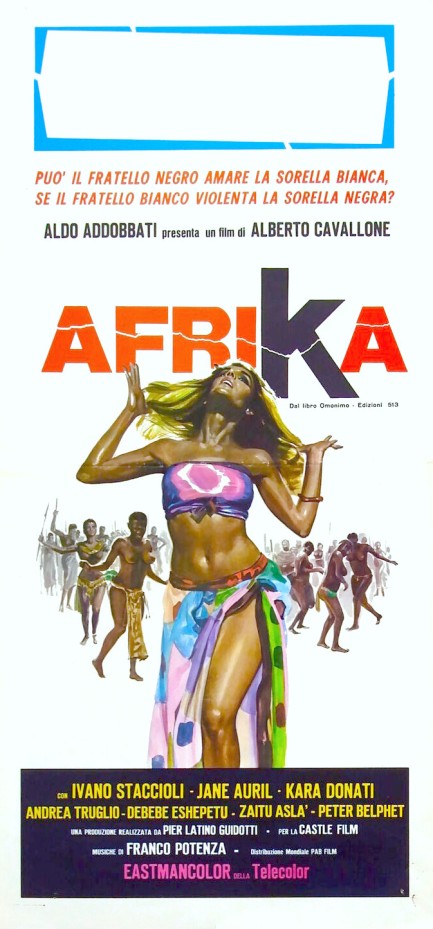

This is an interesting but uncredited Italian poster for the Alberto Cavallone directed and written Africasploitation flick Afrika (clever name, right?), which premiered in Italy today in 1973. By now you know exactly what to expect. What's amazing about these set-in-Africa movies, whether Italian, German, British, French, or what-have-you, is that they portray the continent as lawless and cruel (cue gratuitous shot of ox being decapitated) in a way that's bemusingly lacking in self-awareness coming from cultures that murdered one-hundred million inhabitants of those lands in the pursuit of profit.

On the lighter side, if we'd been customs agents anywhere in the tropics during the 1970s, we'd have taken aside every white arrival, looked over their paperwork, and said with a straight face, “It indicates here you boarded the flight with your usual inhibitions, but I notice you don't seem to have any with you now.” If only we had a time machine. With luck we'd have “processed” Anita Strindberg and Yanti Somer. At this point we accept whites-in-the-tropics movies as cinematic exercises in behavioural guardrail smashing. Sometimes those exercises are actually good, loaded with cliché though they may be. However Afrika, while suffering from the same old blind spot, attempts a serious story with a modicum of depth.

Set in Ethiopia, it's about a painter played by Ivano Staccioli who's tempted to stray from his wife when he meets a handsome gay college student played by Andrea Traglia. The studious and poetic Traglia is bullied in school, even raped at one point, and finds sympathy and understanding with Staccioli, and a job as his live-in secretary. This is not an easy household in which to live because its occupants are decadent and neurotic. Staccioli and Traglia's relationship is the sanest thing going on, but needless to say, it will lead to trouble and tragedy. This is all framed by a murder-or-suicide and police investigation, which means the central drama of a forbidden gay affair is told in flashback during interrogations.

We appreciated Cavallone taking a swing at a serious drama, and we enjoyed seeing Maria Pia Luzi, one of Italy's many exploitation stars (Women in Cell Block 7, White Slave Ship), given a chance to act rather than strip, but we can't call the movie good. It isn't the performances—everyone does pretty well in that department, considering the level of writing. It's just that the film is portentous and uninvolving. Take away the anti-Africa bias and it's a noble attempt at important subject matter, but in cinema you don't get points for trying. In our opinion you can give Afrika a pass.

The journey to becoming her true self.

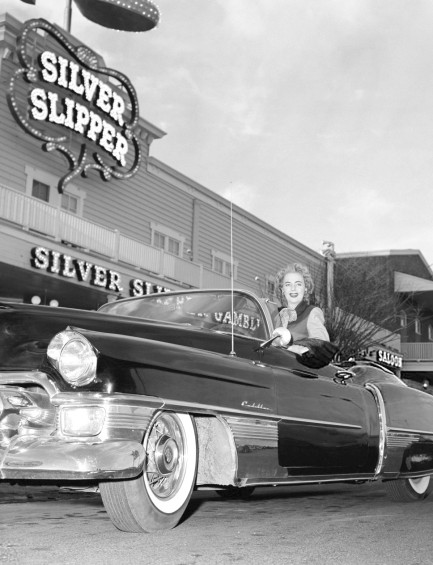

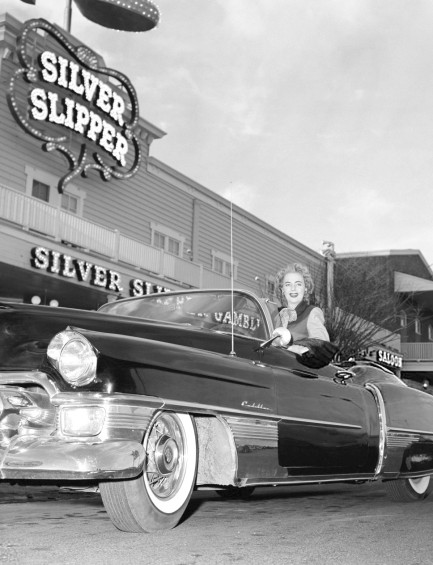

We found these photos at a very interesting website called Vintage Las Vegas, which could be the number one online repository for historical Sin City photos. What they show is trans star Christine Jorgensen, who sometime this month in 1955 posed for these photos at the Silver Slipper casino. In the first she's seated in a sweet Cadillac Eldorado convertible, the 1954 model, which you can tell by the shape of the chrome fender accents. At the time Jorgensen was globally famous as one of the first men to surgically become a woman, and was performing all around the U.S. as a singer and dancer.

We first shared Jorgensen on our website way back in 2011, and since then people like her have been posited as the enemy of all that is good. Well, as far as we know Jorgensen just wanted to live her best life, as did the many other famous trans personalities of the mid-century era such as Coccinelle, Gayle Sherman, Abby Sinclair, Ajita Wilson, Tula Cossey, April Ashley, and Roxanne Alegria. That many? Yeah. The trans community has been around a long time. It's only the panic that's new—and misdirected.

Shhh! Character assassination in progress.

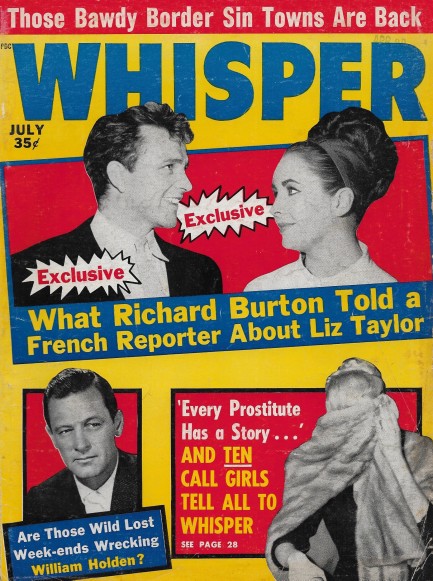

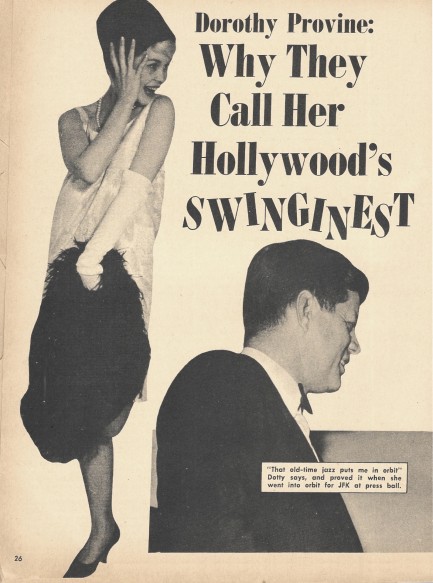

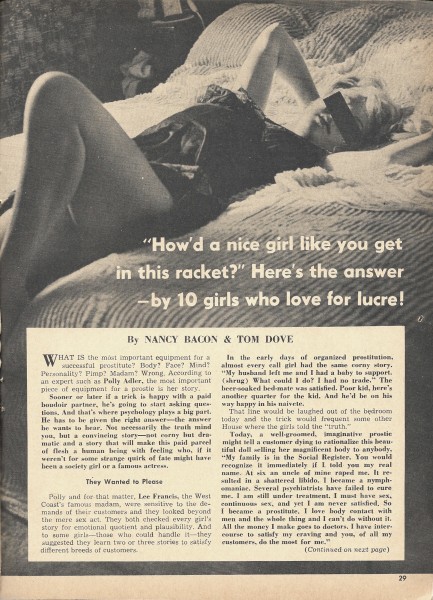

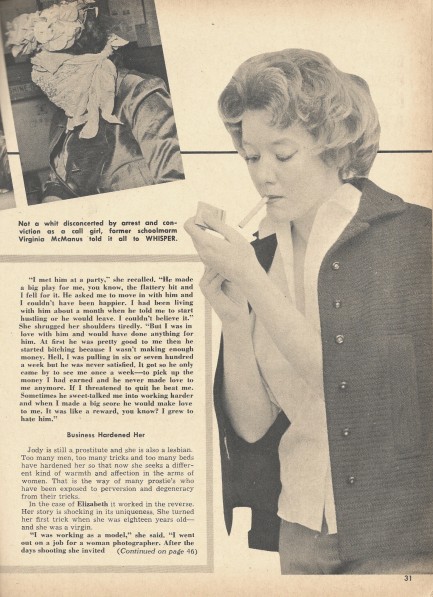

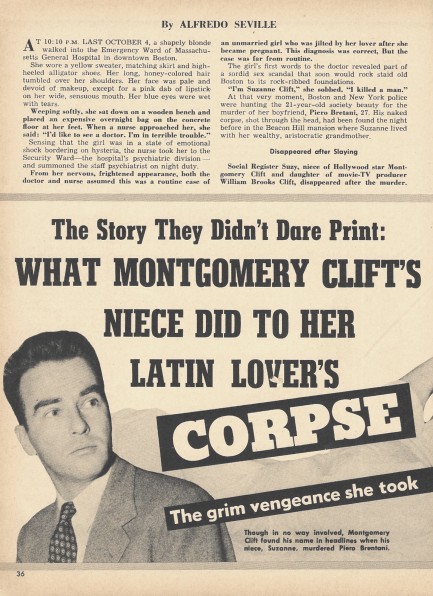

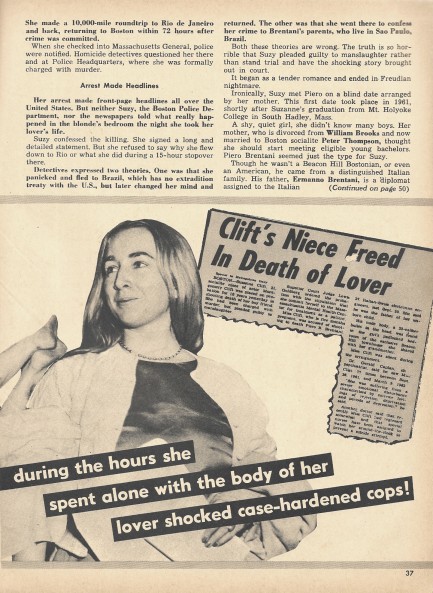

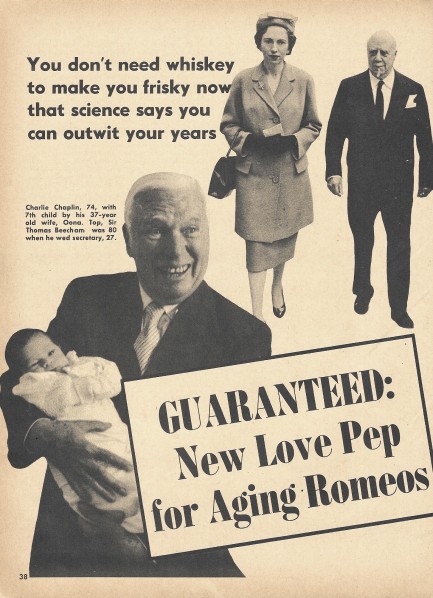

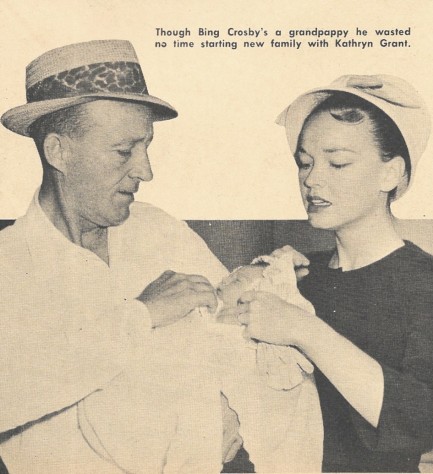

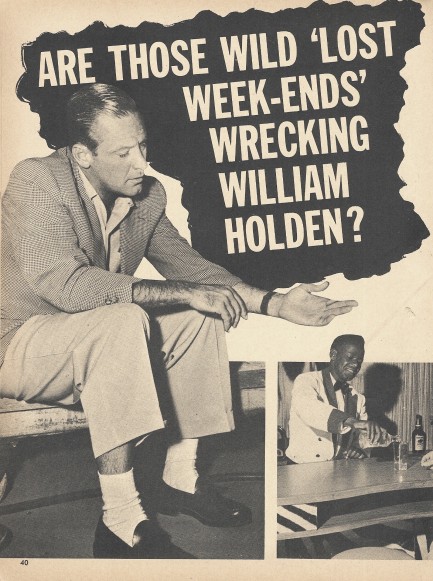

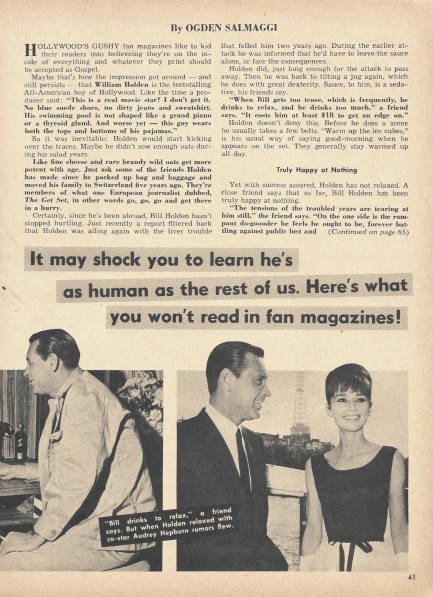

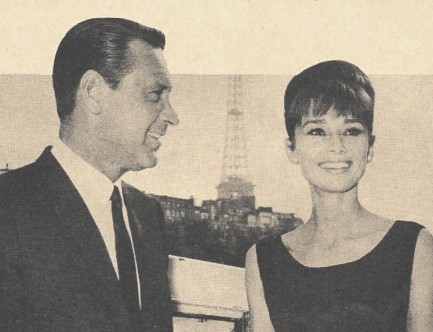

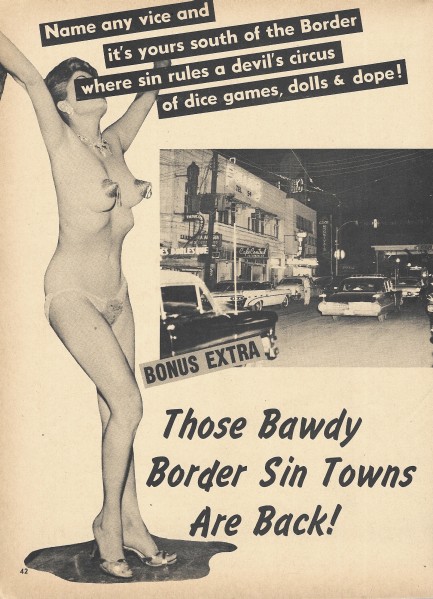

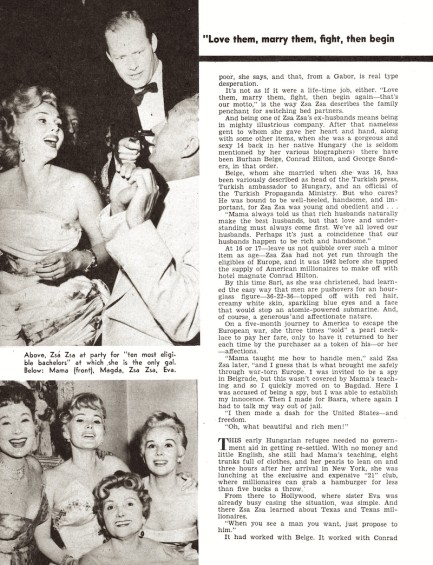

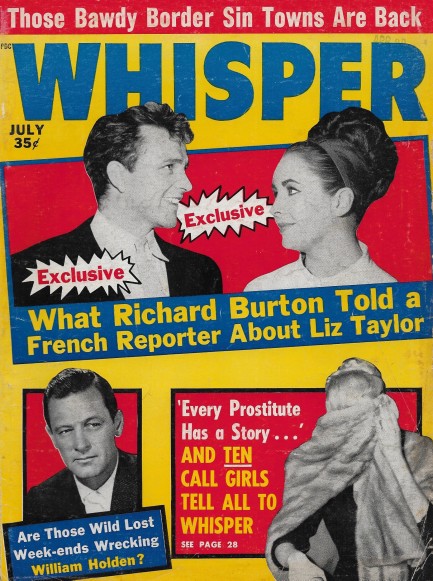

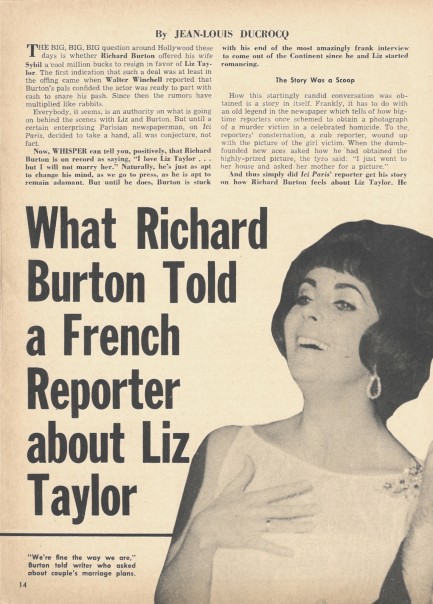

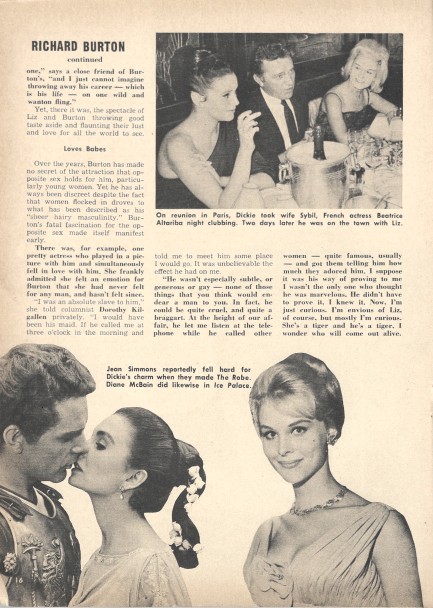

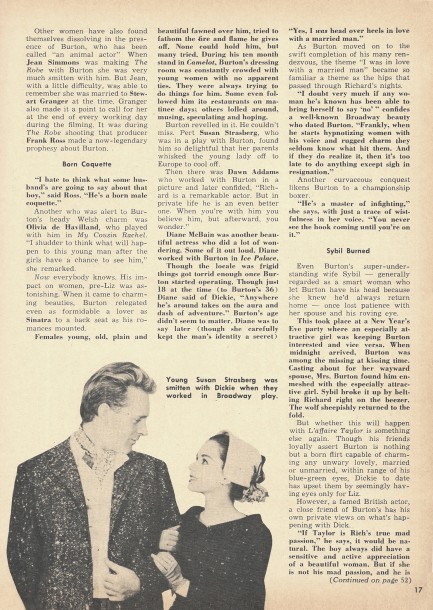

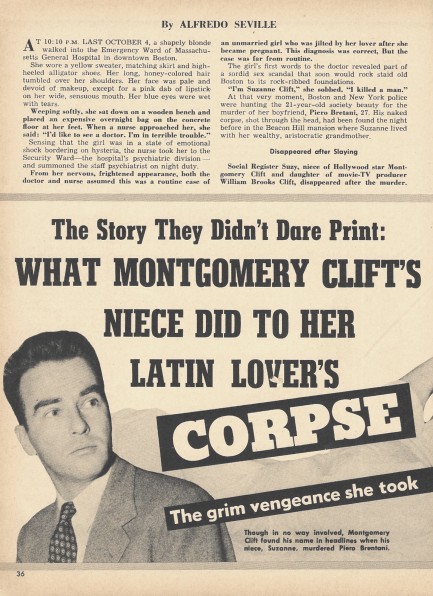

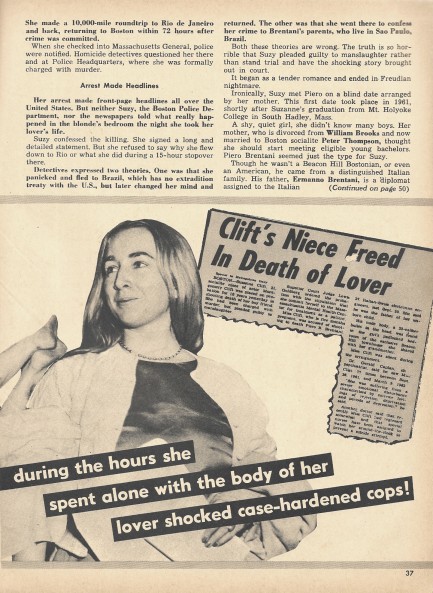

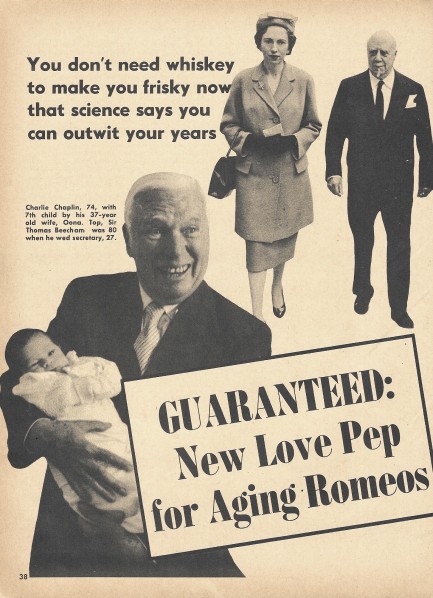

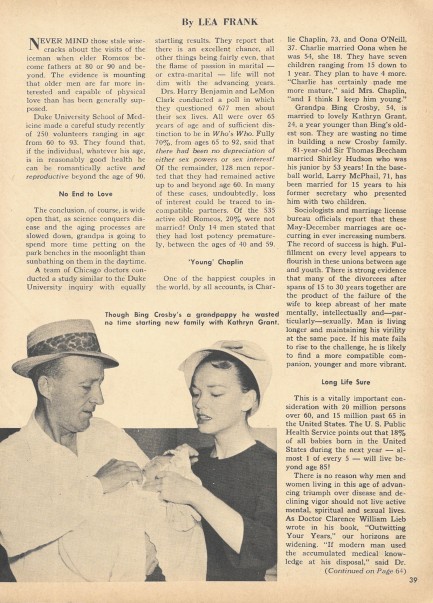

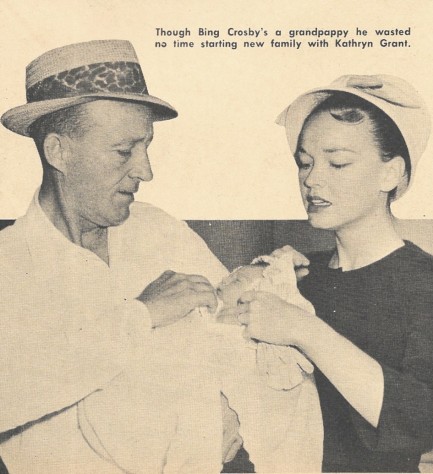

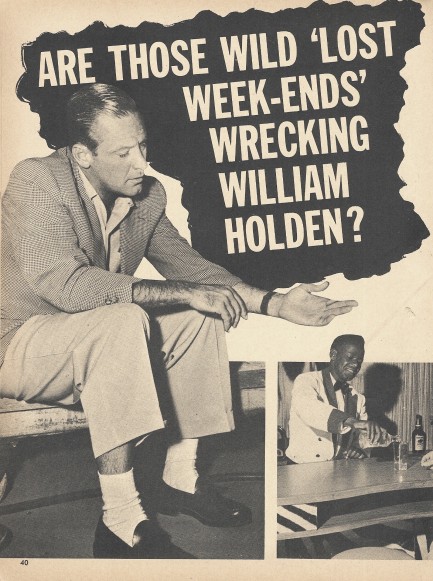

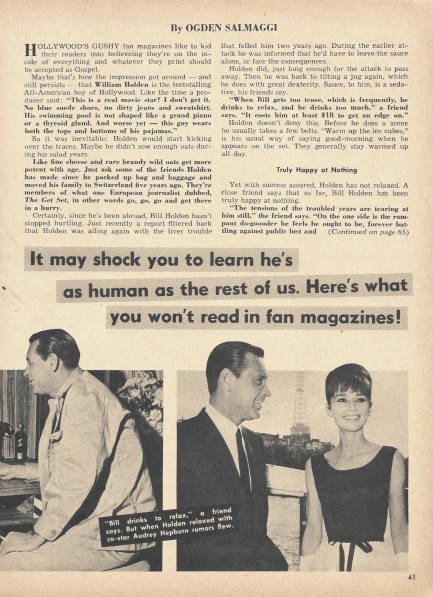

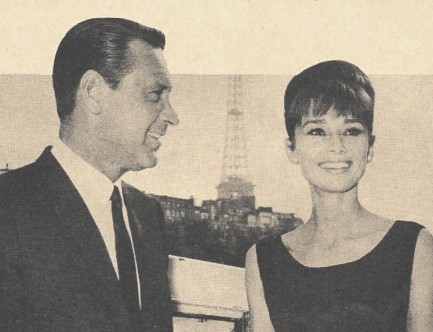

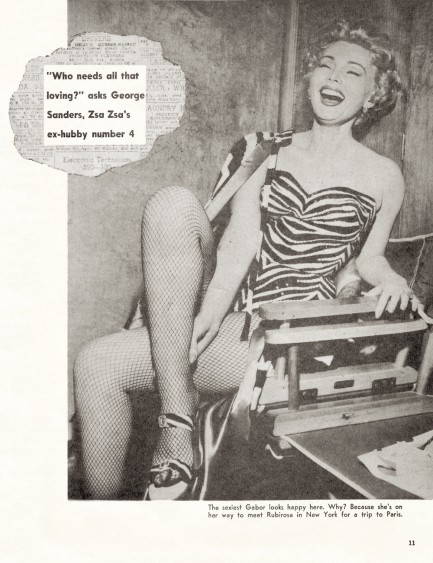

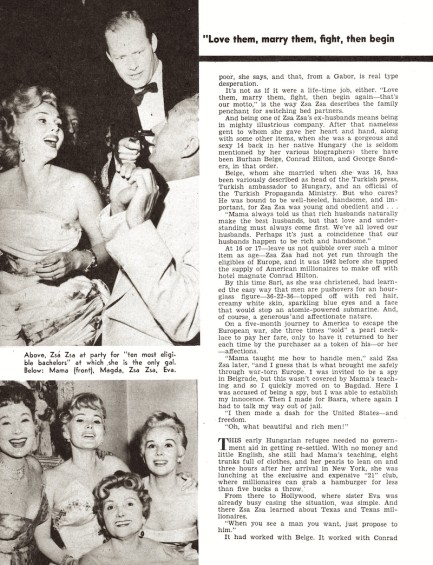

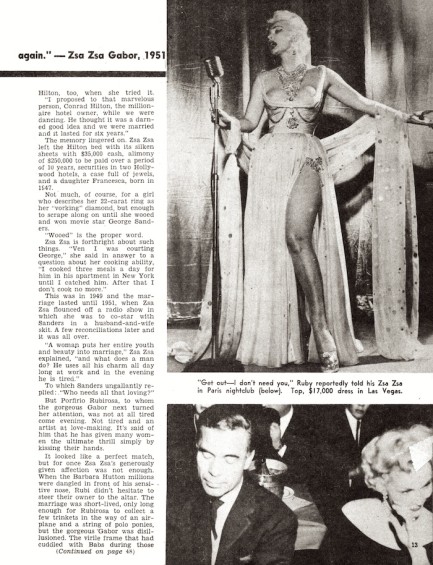

Above are some scans from an issue of the tabloid Whisper published this month in 1963. We've shared hundreds of tabloids over the years, and we always marvel at them. How would you describe the compulsive need to know what's going on in other people's lives? Is it a from of comparison? Is it schadenfreude? Is it envy? The American Psychological Association calls it natural behavior stemming from the fact that humans are social animals curious about what's going on around them. It's why, according to the APA, we gossip about friends and neighbors. Your first thought, in terms of tabloids, might be that celebrities are neither friends nor neighbors. However, the headshrinkers tell us they are. People create parasocial relationships with celebrities, and thus the same dynamic exists. And nobody is immune. Condescending remarks about celebrity gossip are liable to come from people inordinately involved with their favorite baseball player, acclaimed author, or television talking head. Some people let celebrity fashionistas suggest what they should wear, while others who consider themselves above such silliness let television pundits tell them who to hate.

We find mid-century tabloids incredibly interesting, even if everybody being gossiped about is long departed. The robust sales of tabloids on auction sites seems to confirm that we aren't alone. In this issue Whisper digs dirt on numerous titans of celebritydom—Elizabeth Taylor, Richard Burton, Audrey Hepburn, Bing Crosby, Charlie Chaplin, and others. Editors also let their bigot flags fly by predicting “one of the most sinister trends in history—an organized homosexual drive” to take over the U.S. That one still sells in some quarters. We'll have more from Whisper soon.

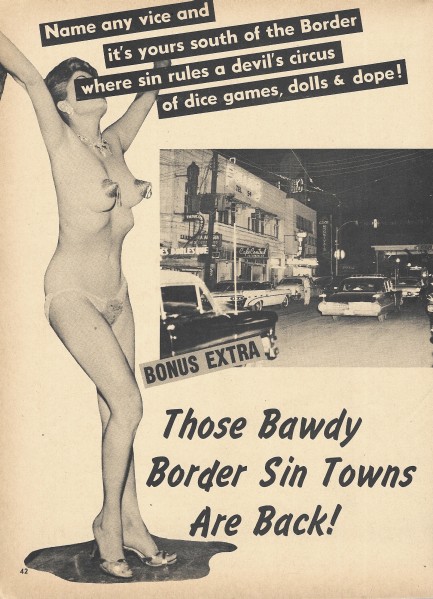

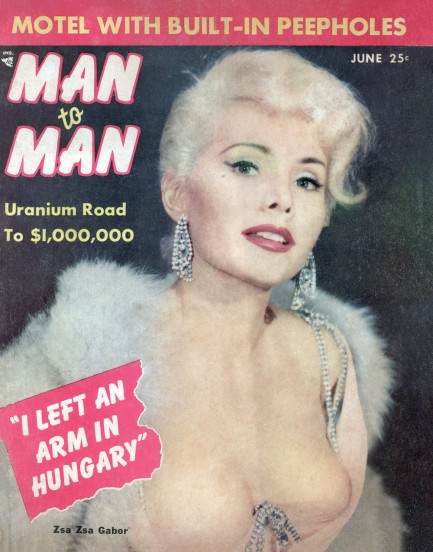

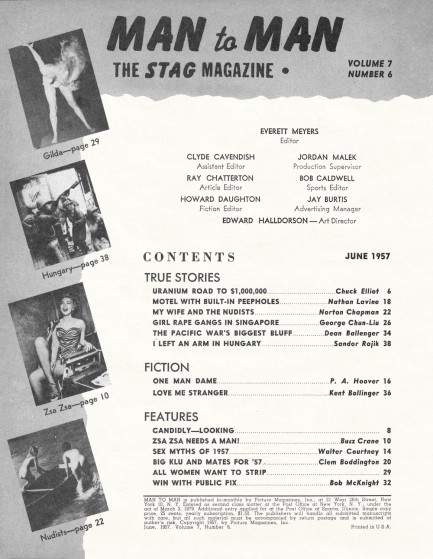

The more things change the more they stay the same.

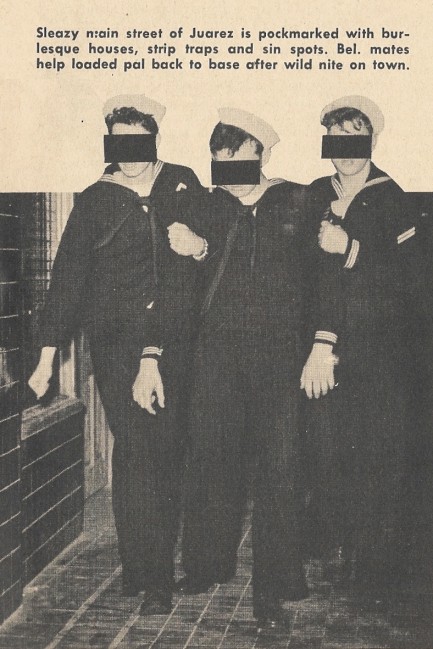

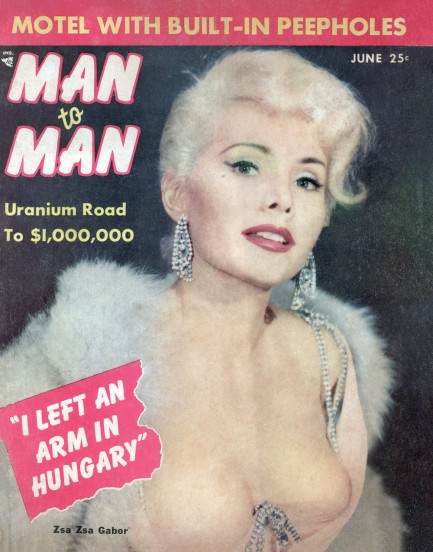

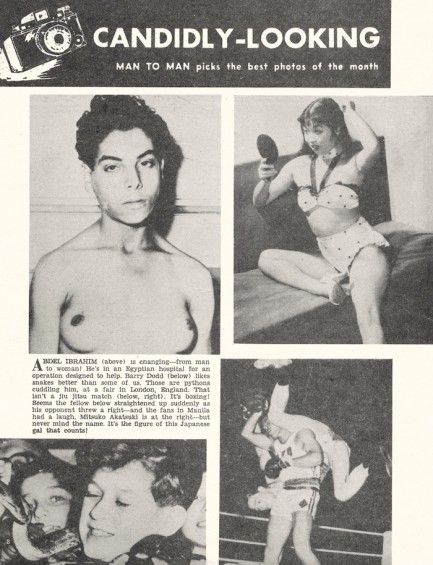

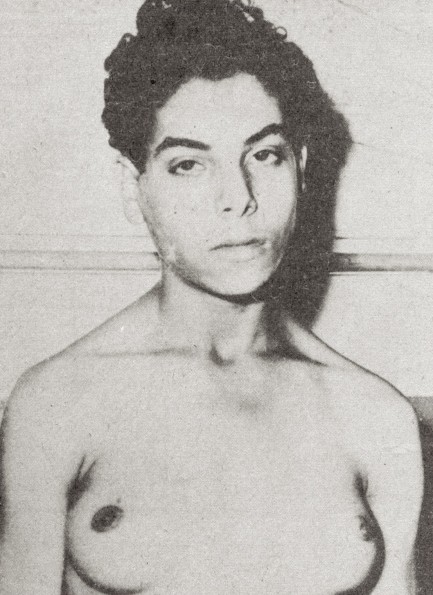

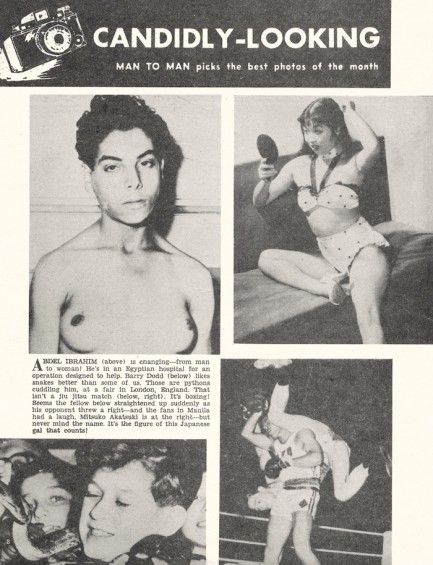

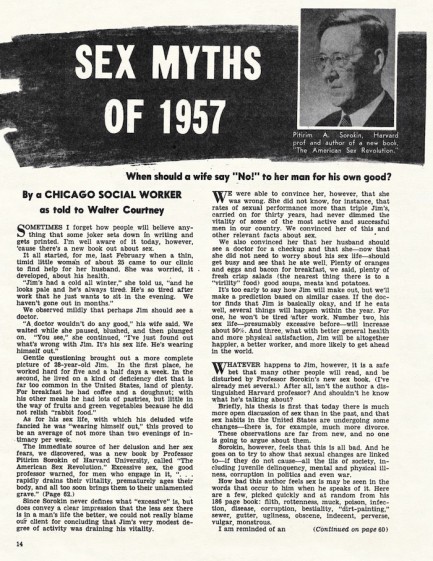

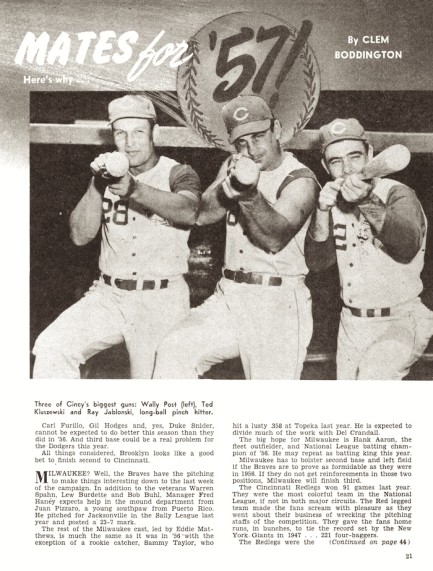

Reading old magazines has helped teach us that things have not changed as much as some people would like you to believe. This issue of Man to Man hit newsstands this month in 1957. We've now seen trans stories in nine mid-century publications, and keep in mind we've not seen even a fraction of a percent of all the magazines ever published. The person under the spotlight this time is Abdel Ibrahim, and Man to Man editors say about him merely that he's “changing from a man into a woman,” and, “he's in an Egyptian hospital for an operation designed to help.”

This dispassionate tone has been the norm, from what we've seen, and shows yet again how the process of creating hysterical prejudice works. First, you train people to believe something unprecedented is occurring, then you frame that as a threat to people's “way of life.” But these old tabs serve as an inconvenient truth—sex reassignments have been around for quite a while, and before then, men who passed or attempted to pass as women go back into the depths of history.

During the mid-century era many trans people became national or international celebrities, from Coccinelle to Christine Jorgensen to Ajita Wilson. The knowledge of transexuals was so mainstream that the top-selling tabloid Whisper even published a 1965 story titled, “A Doctor Answers What Everyone Wants To Know About Sex Change Operations,” with the key word in that header—everyone—suggesting that the dominant reaction socially speaking was neither anger nor fear.

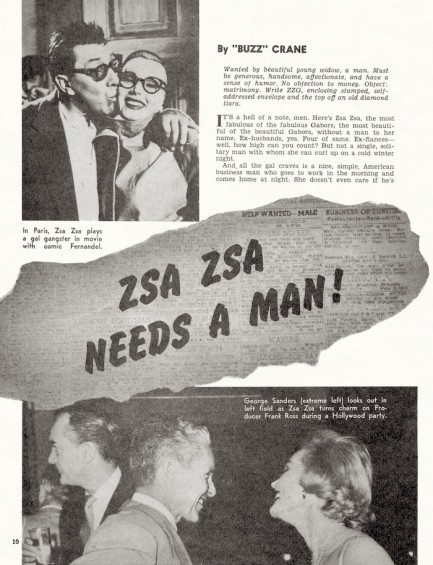

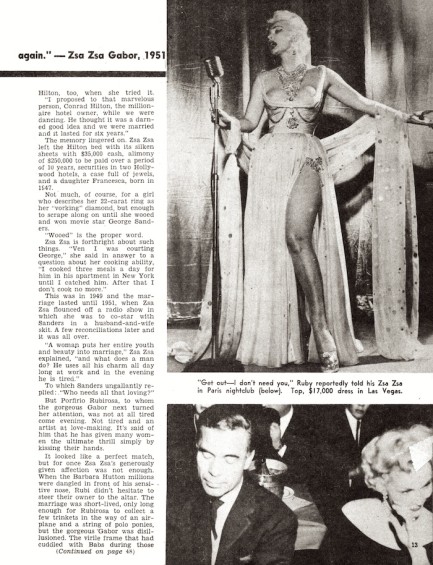

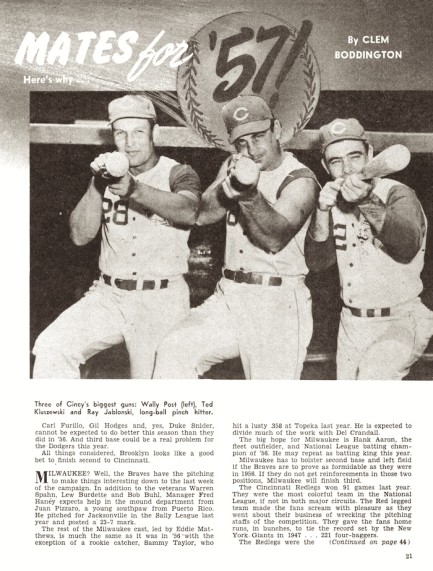

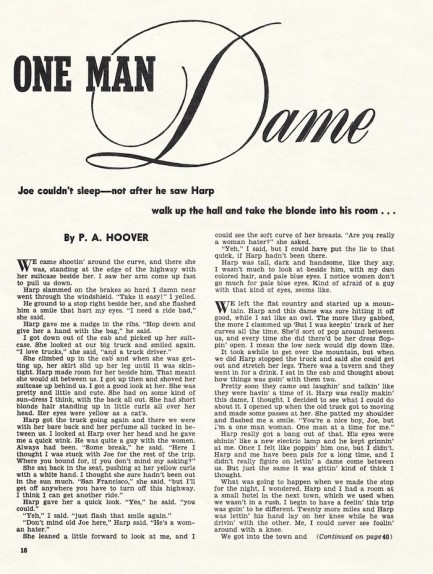

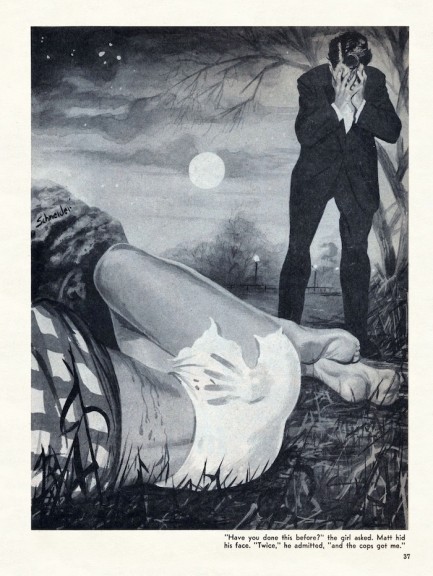

Elsewhere in Man to Man you get Zsa Zsa Gabor, including in one photo that looks familiar, sex myths of 1957, motel peepers, war, crime, fiction, a bit of nudism, and a bit of burlesque. You also get two pieces of art from popular illustrator Mark Schneider, who we've highlighted before. He mainly worked for Sir! magazine. We put together a collection of his covers for that publication which you can see here. You can also see three more issues of Man to Man by clicking its keywords below and scrolling down.

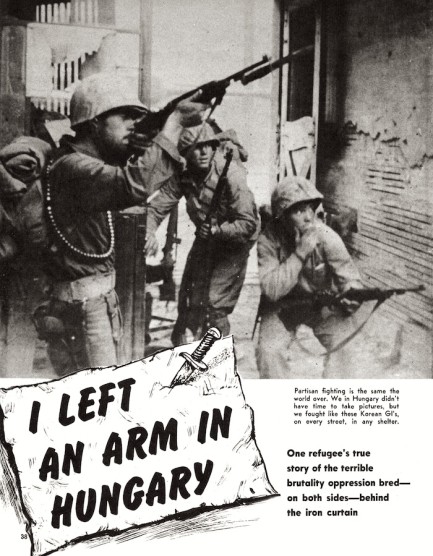

National Bulletin's fake cover story was unconscionable even in 1972.

This issue of National Bulletin published today in 1972 features a cover touting rapists going on strike. Do we have any doubt that this sprang from the brows of middle-aged editors with smoker's coughs, fallen arches, and no dates? As we've documented before, cheapie tabloids often trafficked in such imaginary stories. This one is akin to comedy—unamusing, tone-deaf comedy. The gist is that the head of RUFF—the Rapist's Union for Fun and Frolics—says raping women isn't fun anymore because they're too liberated and actually enjoy it. It would have been crude already in 1972 (that's why the editors did it), but these days such sentiments send a cringe through the deepest recesses of your body. The honchos at National Bulletin would, of course, say they're just riffing, yet the fact that the idea was considered by them to be viable as humor still says so much. And what it says isn't good.

So why share such items? Well, we're mainly interested in the art and graphics of old paperbacks and movie posters, and the rare photos of celebrities found in period tabloids. There are starphotos in these publications that literally don't exist online until we upload them. As lovers of old Hollywood, it's mandatory that we do so. But also, in our view, it's important to document vintage social attitudes. And here's why—after enough time passes it's easy for bad faith entities to pretend such beliefs never existed. Sharing these tabloids reminds us both of where we came from, and where we're going. In terms of promotional art and aesthetics, we believe we've ended up someplace worse than before—no matter how many book design awards are given to whichever Photoshopped covers of whatever year. Conversely, in terms of social development, we believe things are generally—despite an eddy of a few years or a decade here or there—improving.

So we're presented with divergent movement—trains traveling in opposite directions on parallel tracks during the mid-century era. On one track is excellent and commemorable visual content, and on the other is a set of social attitudes with which we tend to disagree. While it's true we could separate the art from its context, we think that's a bad practice. Many of the emails we've gotten from students, researchers, filmmakers, writers, and history buffs curious about these magazines indicate to us that without context, understanding the true characteristics of art is impossible. It'd be like looking at Picasso's “Guernica” without knowing there was such as thing as the Spanish Civil War. Yeah, it's still a great painting. But knowing its political genesis makes it more interesting. Knowledge is armor.

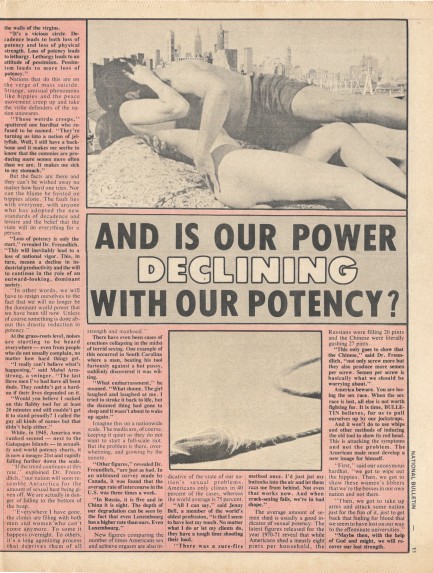

Bulletin moves on from the fictional rape story to offer up slightly less horrible fare in its other pages. Readers learn about lesbian communes, consensual bondage, prostitute conservationists, and sexually depraved athletes. Editors also tell readers Americans are losing the “sex race”—i.e. formerly virile men are becoming weak and impotent. If you're thinking you've heard similar masculine moaning on modern cable television, you'd be right, but the sad difference is that Bulletin's story is meant to be farce, whereas modern cable news is deadly serious about “feminization.” Accompanying the text is a photo of a woman taking the pants off a smiling wax figure of Richard Nixon. That is legitimately funny. We've enlarged it below. Feel free to spread that marvelous image far and wide. More tabloids to come.

|

|

The headlines that mattered yesteryear.

2003—Hope Dies

Film legend Bob Hope dies of pneumonia two months after celebrating his 100th birthday. 1945—Churchill Given the Sack

In spite of admiring Winston Churchill as a great wartime leader, Britons elect

Clement Attlee the nation's new prime minister in a sweeping victory for the Labour Party over the Conservatives. 1952—Evita Peron Dies

Eva Duarte de Peron, aka Evita, wife of the president of the Argentine Republic, dies from cancer at age 33. Evita had brought the working classes into a position of political power never witnessed before, but was hated by the nation's powerful military class. She is lain to rest in Milan, Italy in a secret grave under a nun's name, but is eventually returned to Argentina for reburial beside her husband in 1974. 1943—Mussolini Calls It Quits

Italian dictator Benito Mussolini steps down as head of the armed forces and the government. It soon becomes clear that Il Duce did not relinquish power voluntarily, but was forced to resign after former Fascist colleagues turned against him. He is later installed by Germany as leader of the Italian Social Republic in the north of the country, but is killed by partisans in 1945.

|

|

|

It's easy. We have an uploader that makes it a snap. Use it to submit your art, text, header, and subhead. Your post can be funny, serious, or anything in between, as long as it's vintage pulp. You'll get a byline and experience the fleeting pride of free authorship. We'll edit your post for typos, but the rest is up to you. Click here to give us your best shot.

|

|

as prisoners in order to aid the infiltration of the camp. Behind bars is one inmate—Wilson—who has the shining or something, and keeps telling the others that violence, death, and freedom are coming. Also coming are WIP staples such as the evil wardenness, languorous shower scenes, whippings, baroque tortures, and sexual assault. It all ends pro forma with a climactic shootout.

as prisoners in order to aid the infiltration of the camp. Behind bars is one inmate—Wilson—who has the shining or something, and keeps telling the others that violence, death, and freedom are coming. Also coming are WIP staples such as the evil wardenness, languorous shower scenes, whippings, baroque tortures, and sexual assault. It all ends pro forma with a climactic shootout.