The very moment you need help is the moment there's nobody around.

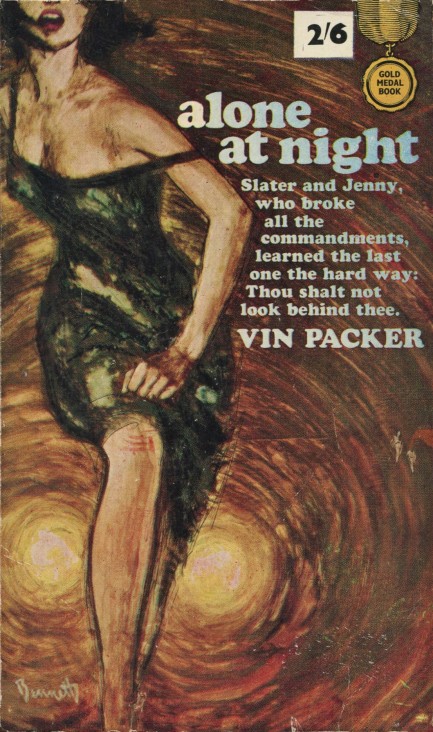

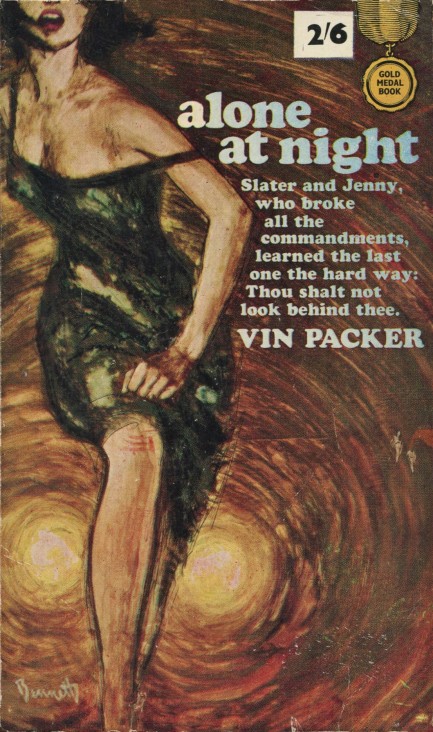

Harry Bennett put together yet another a unique paperback cover, this time for Vin Packer's 1963 novel Alone at Night. Bennett was a master illustrator who specialized in loose yet highly skilled pieces, but he had a range that we've marveled over many times. Just check his solidly representational efforts here, here, and here, as opposed to his somewhat more abstract stylings here and here, then note how he splits the difference between the two here. He's always interesting, and Alone at Night is also an interesting novel.

Vin Packer was a pseudonym for Marijane Meaker, and she sets her story in the actual small town of Cayuta, located in south central New York state. She tells us about a man named Donald Cloward who's sent to prison for fatally running over a woman. By the time he's paroled eight years later he's come to doubt the official story. On the night in question he'd been nearly incapacitated by alcohol, and had blacked out the events, yet has the vaguest memory of being placed behind the wheel of the deadly car—presumably by someone who wanted him to crash and be killed. Once dead, people would assume he stole the car.

Who would do such a thing? His father-in-law, possibly. He had offered his sedan though Cloward was clearly unable to drive. Since his father-in-law loathes him, and is not a generous man—certainly not enough to lend anyone his car—his guilt seems a good bet. On the other hand, the woman who was killed happened to be the wife of a man who desperately wanted out of his marriage in order to wed someone else. Maybe he arranged everything. After all, Cloward was found in that man's Jaguar. Yes, there may have been a switch. Cloward thinks he remembers getting into one car, even though he ended up in another. Is it a false memory?

Alone at Night is built around a leapfrogging present-past structure, and has a multi-pov narrative in which the reader soon knows all, but the characters don't. In trying to sort it all out, Cloward decides that his father-in-law moved him from the sedan to the Jaguar after realizing the second car was already pointed toward the drop-off of a cliff. After all, why merely hope for a road accident when one is already likely just by virtue of the choice of a parking space? But is he missing a few pieces of the puzzle? We won't say more about the plot. This is excellent work from Packer/Meaker. It's our second book from her, and won't be our last.

He can run from the past but he can't hide.

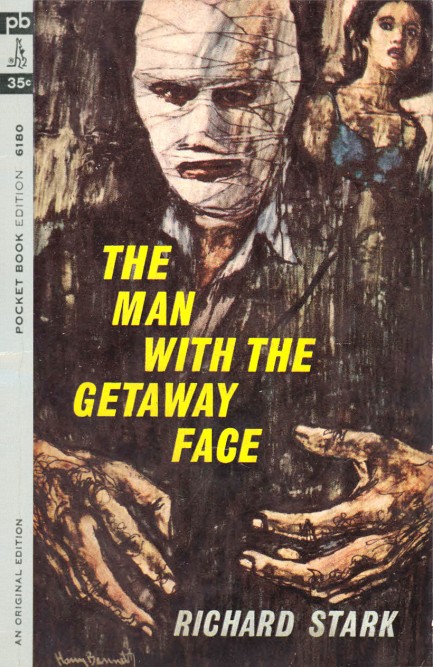

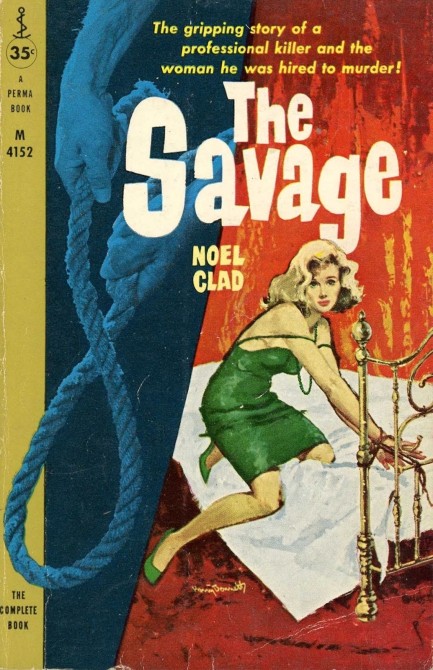

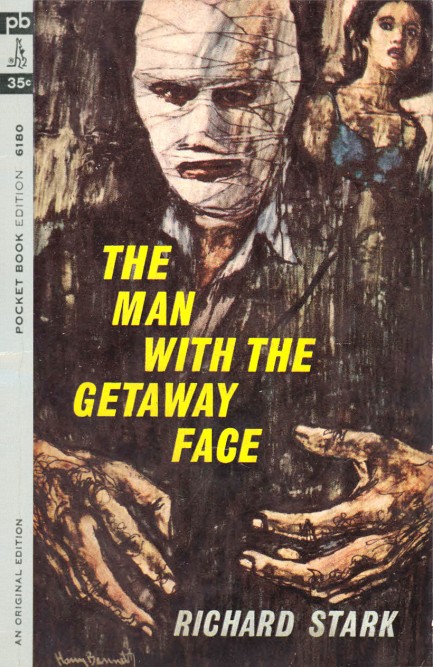

It took us a while but we've returned to Richard Stark, aka Donald E. Westlake, and his Parker series. We read entry one a few years ago. 1963's The Man with the Getaway Face is number two. The cover art here is by Harry Bennett and he basically copied his cover for book one, but changed the background and added the facial bandages. Those bandages reveal the premise—Parker has had a cosmetic surgeon change his face in order to help him evade “the Outfit,” who owe him in spades for various transgressions.

But Getaway Face doesn't focus on Parker's pursuers. Clearly, that's coming in the future. In the here and now he needs money, so he signs onto an armored car robbery, which, in adherence to the pulp law of tenuous connections turning into huge problems, boomerangs in such a way that his face doctor is murdered and Parker is blamed for it. His hands are full: deadly enemies, armed robbery, betrayal, murder, pursuit, and revenge. But he has very big hands. Nice work. We'll read book number three in the series soon.

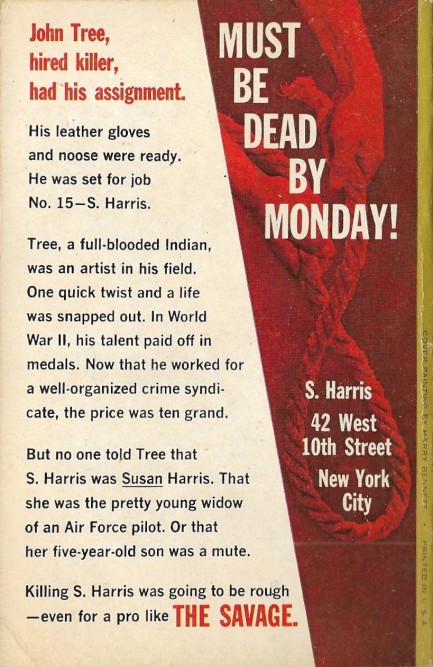

He kills completely without reservation.

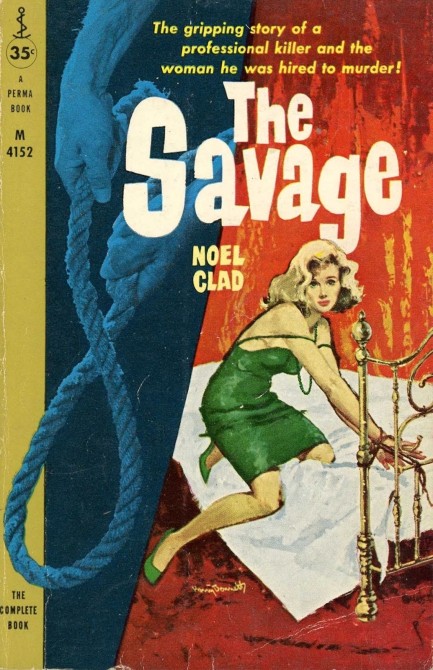

Noel Clad was a promising writer who died in a plane crash when he was thirty-seven. His novel The Savage shows some of that promise. It's about a professional killer named John Tree who's been summoned from his Wyoming ranch by the Chicago syndicate to go to New York City and dispose of an S. Harris. Like many fictional killers Tree has a code: he doesn't kill women. When he arrives in New York he learns that S. Harris is Susan Harris, which dismays him. Then the person who's bought the contract and is calling the shots tells Tree to rape Susan before killing her. Next he finds out she's a single mother with a mute five year-old son. None of it sits well with Tree, but it doesn't cause him to flip sides. He just wants out. He asks to be replaced on the job and be done with the situation. Out of sight, out of mind. His employers agree and send two replacement hired guns to do the job. Tree meets with them and realizes they have no ethics—they will rape their target, and they'll murder her son too.

There are hundreds if not thousands of regular mob hitmen in literature and cinema, so why not do something different? It shouldn't be a controversial idea, but sadly, so many these days consider it to be an assault on territory they own somehow. But diversification isn't a new thing. Clever writers have been doing it all along. Clad does it in The Savage. The killer for hire, the anti-hero John Tree, is full name John Running Tree, member of the Shoshone tribe, Native American by both blood and culture. That simple change takes the book in a different direction than other hitman tales. Here we have a killer who hates to think about his impoverished youth on a reservation, who glorifies Native American tests of manhood, and who sees a stripper wearing a tribal headdress as a prop and is angered. You get interesting passages like this:

Being here made him think of religion and how little he knew and the things that had passed for it when he was little: the spirits and the half-reverent amulets and charms. He remembered as he had not for years the lupine tea they drank for Manhood, remembered the girls on the Station eating mushrooms to see if my true love lies, and his own watching of wood smoke that twisted north when the hunting would be good. Even Tall Kite had no longer really believed in the thousand tribal spirits of the upland and the plain, the grass, the insects, the deer and the hawk. And God, in the Bureau of Indian Affairs, was no more than the price of chocolate milk. But in this hall, he had a pleasant feeling, relaxed, as though he was on a mountain all by himself.

1958 this was written, with loads of identity angst, as if it were published yesterday. John Running Tree moves like a folkloric wraith through New York City and tries to prevent Susan's defilement and death. The transgressiveness of the rape angle surprised us, as did the plot point that Tree kills by wire garrotte (not rope, as shown on the cover), but those added to the stakes of a harrowing and austere tale. Are there negatives? A few. Clad loses his tight control over the narrative from the moment Susan realizes—as she must—that Tree isn't just a nice guy hanging about for fun. Clad later forces the usage of Shoshone pictograms into a scene where the child mutely communicates an important clue. It might have worked under the right conditions, but in this case defied credulity. Other authorial errors accrue. Even so, good book. We'd read Clad again.

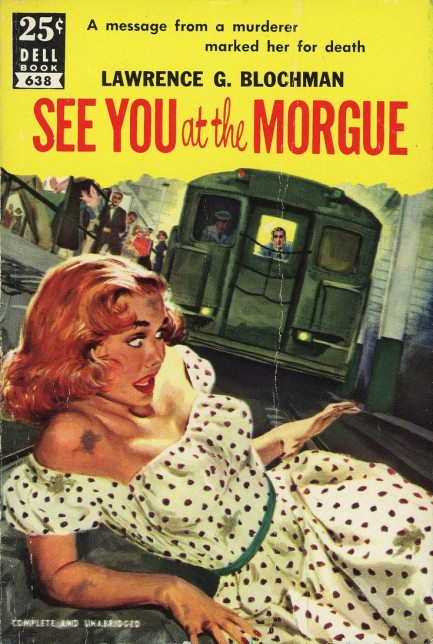

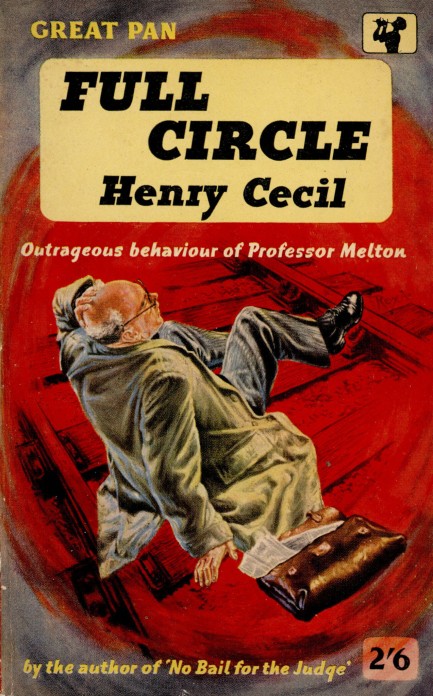

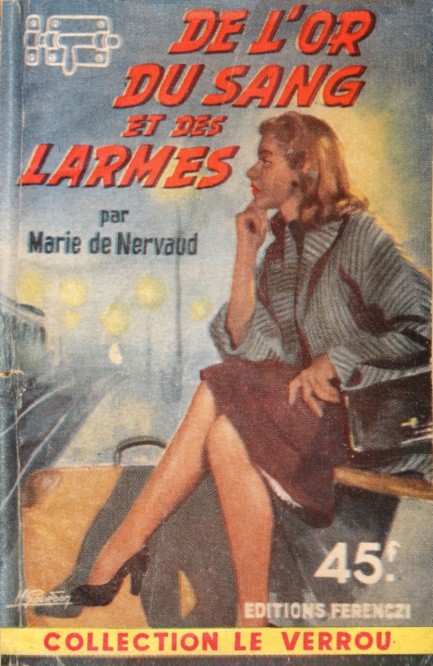

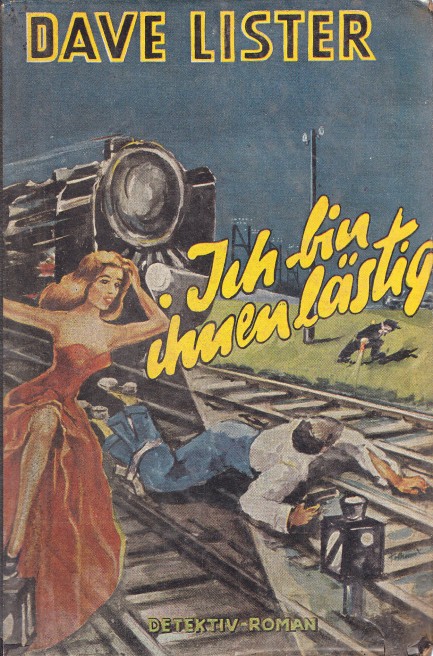

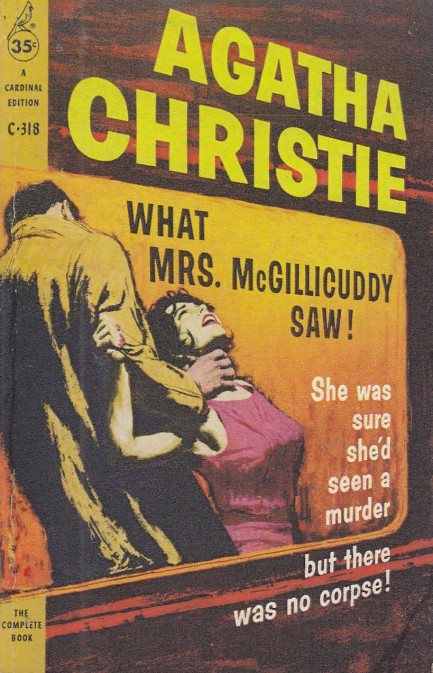

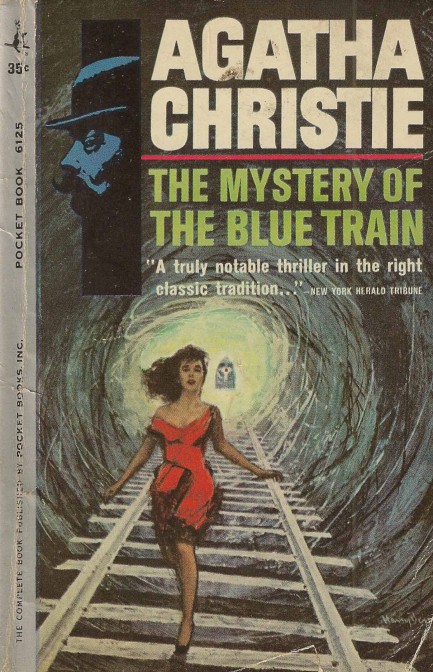

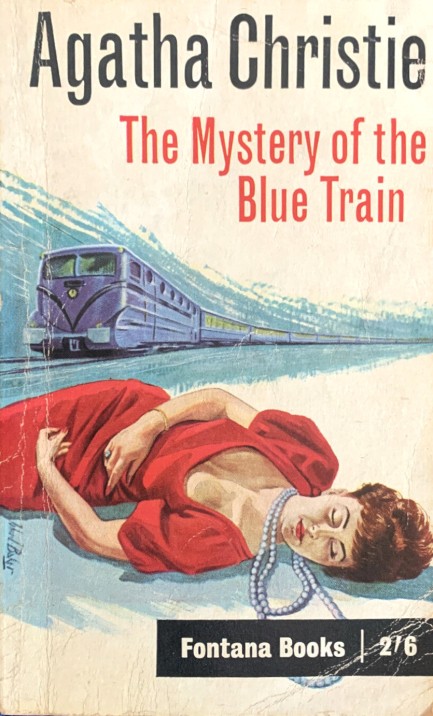

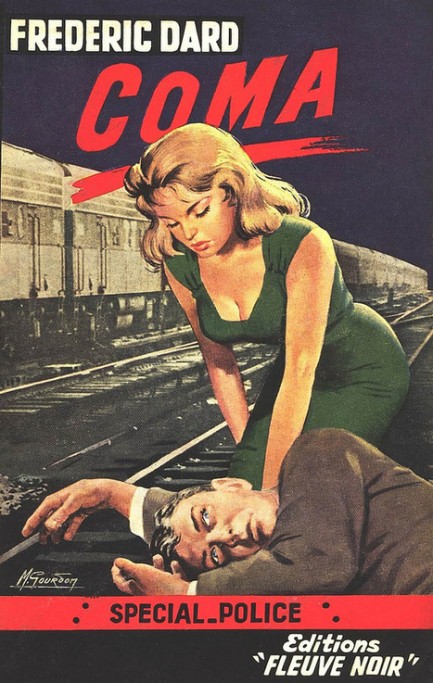

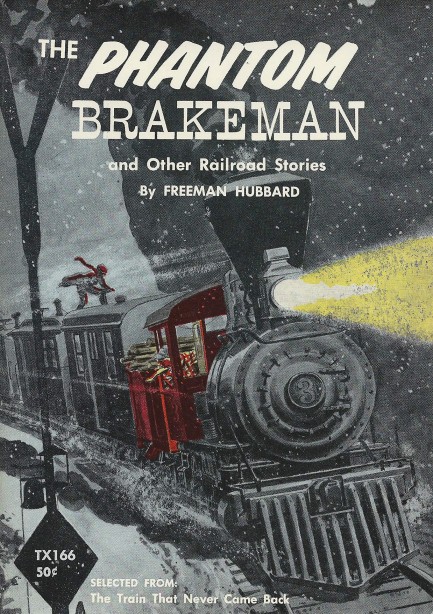

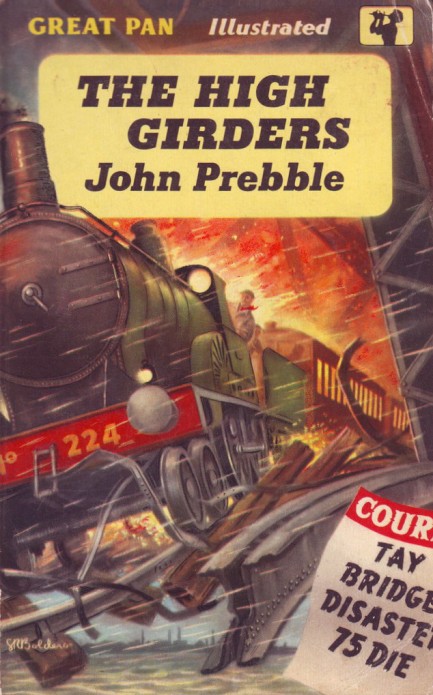

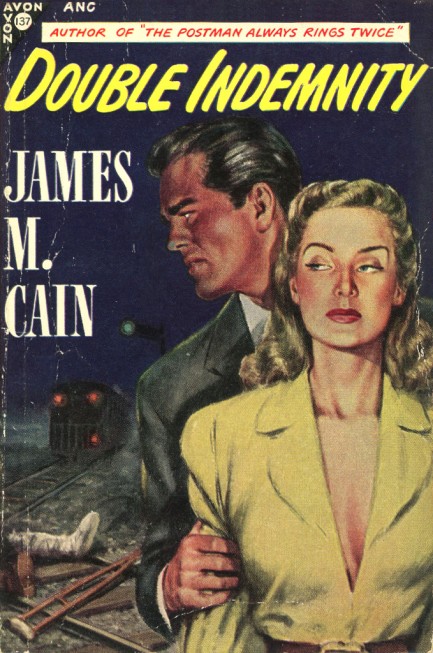

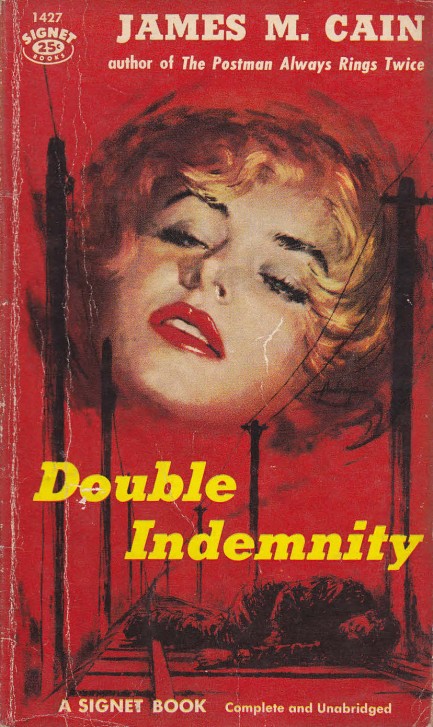

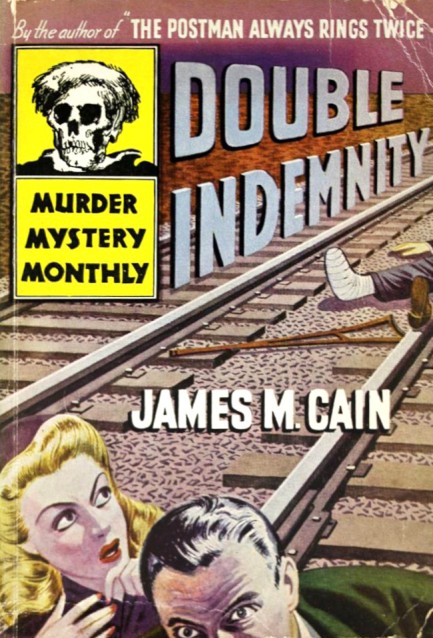

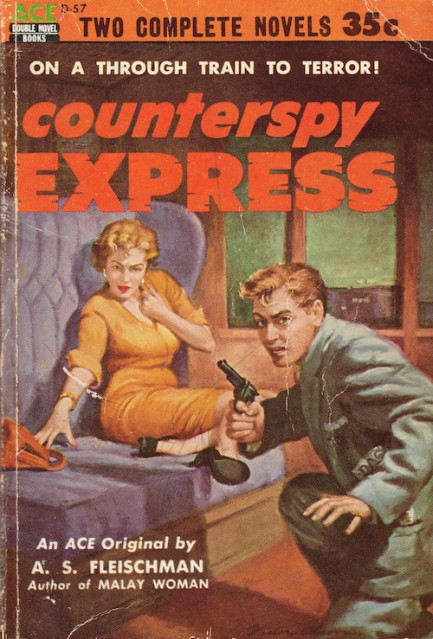

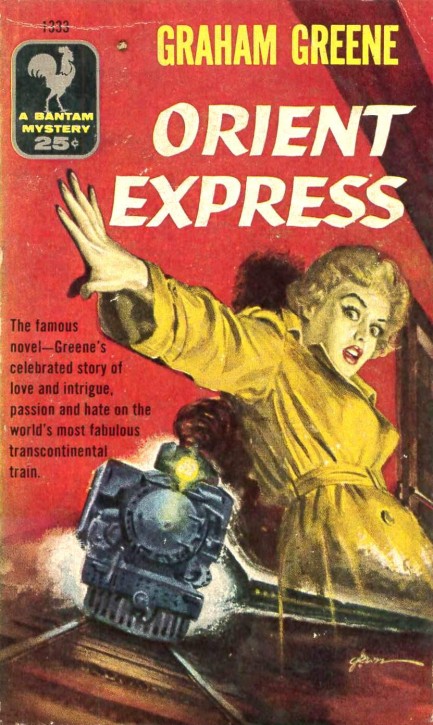

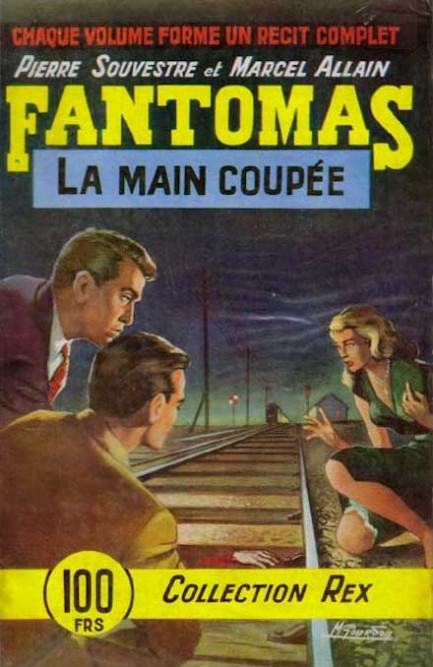

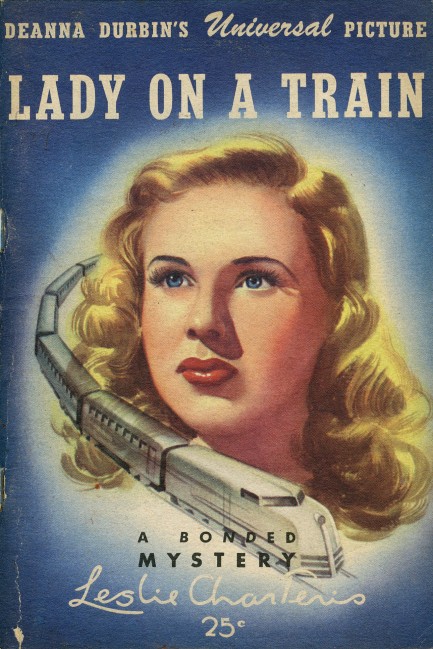

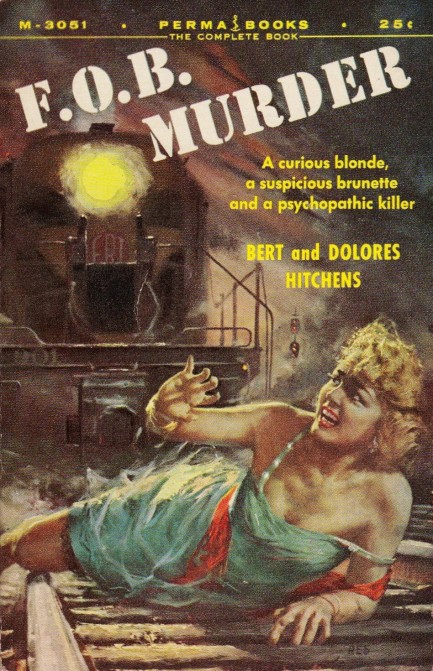

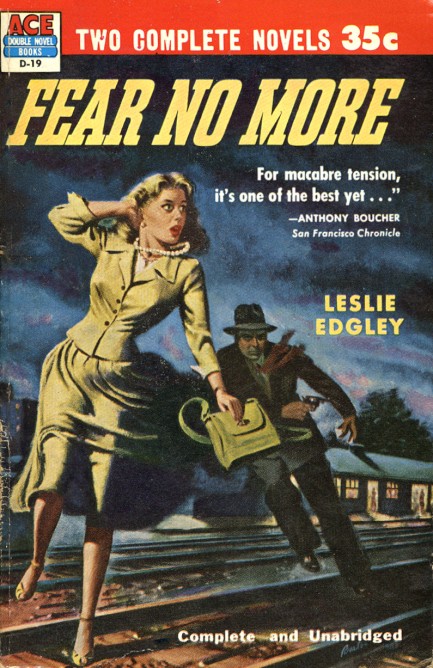

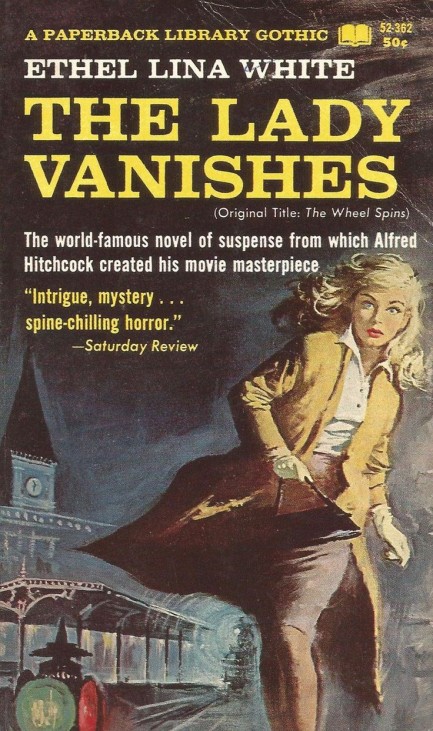

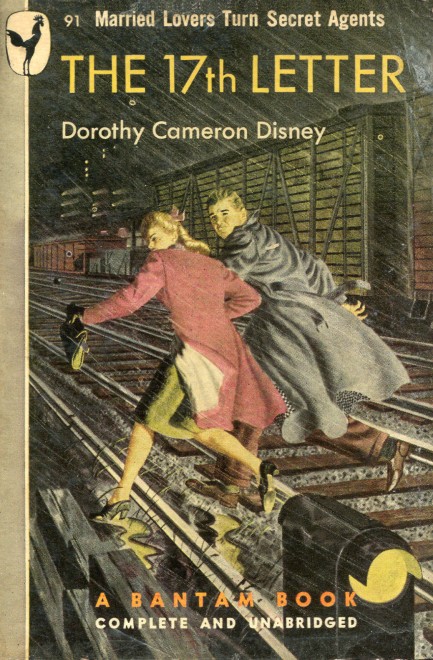

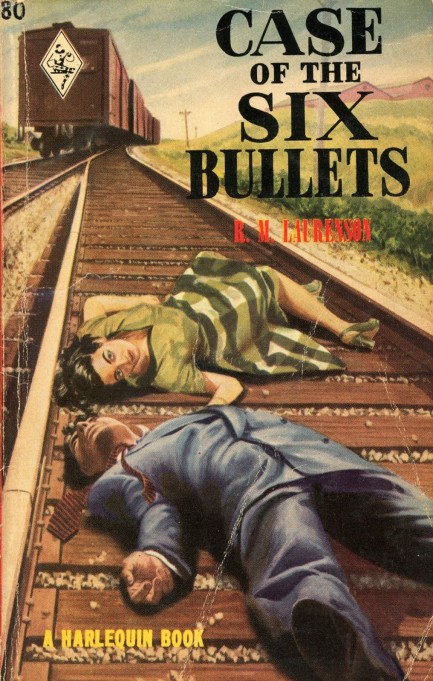

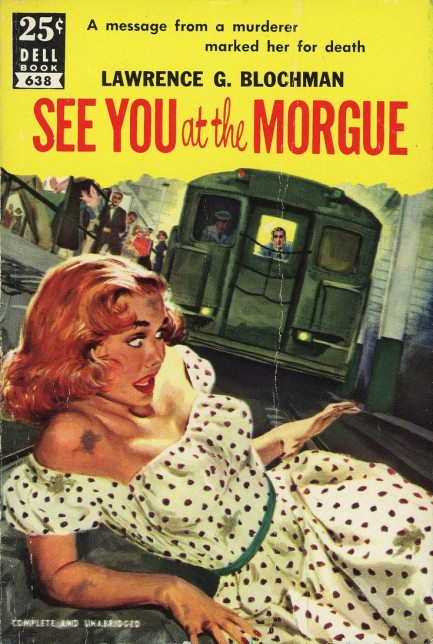

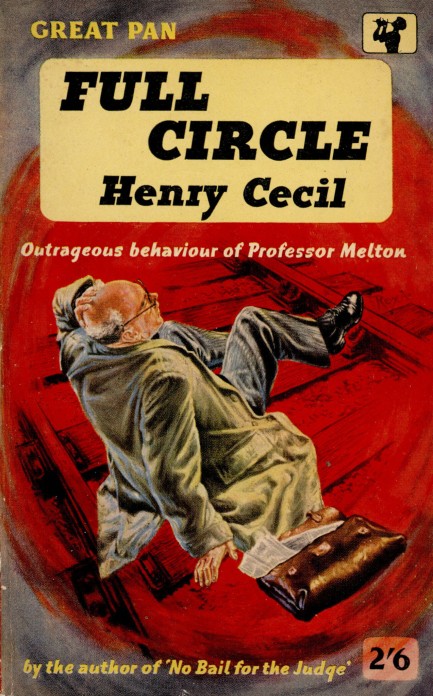

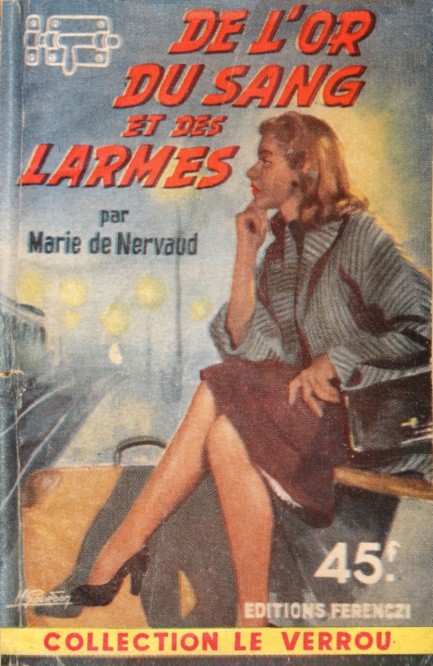

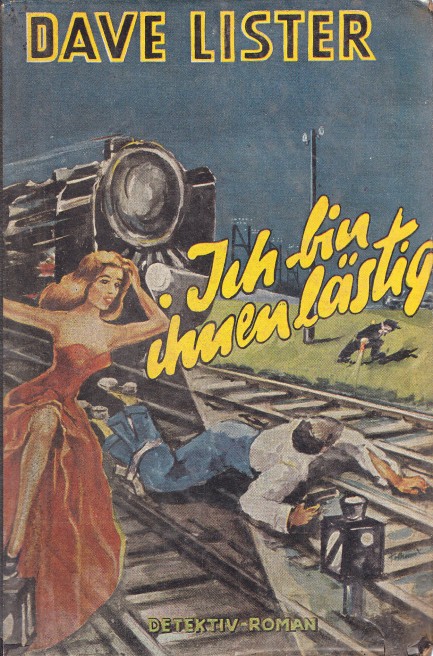

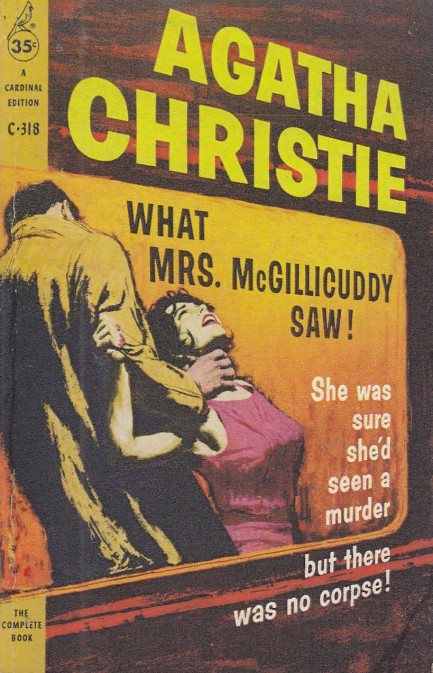

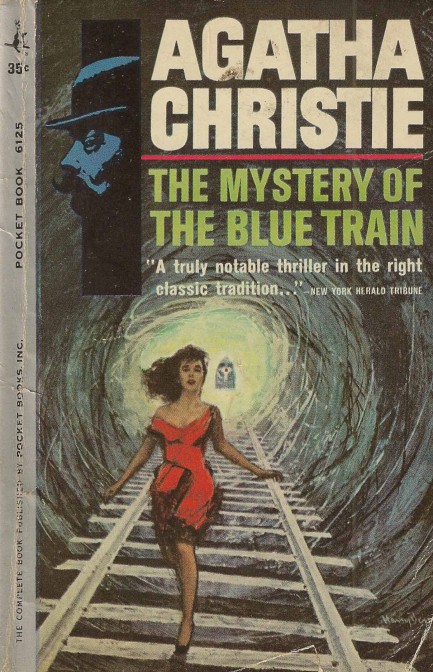

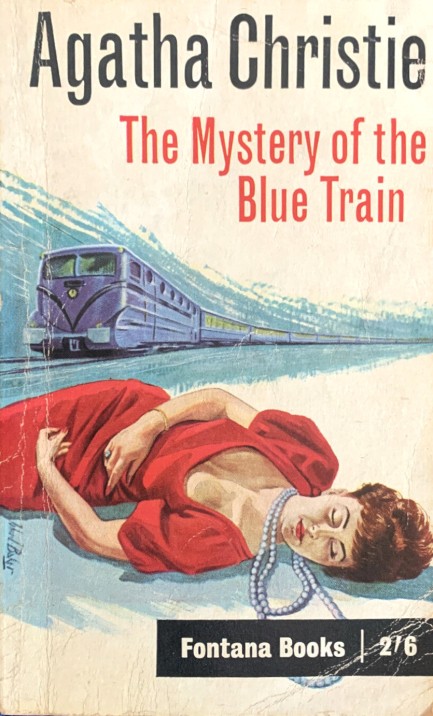

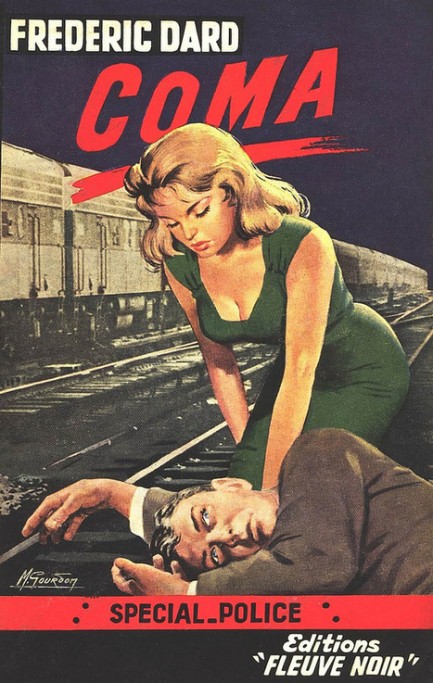

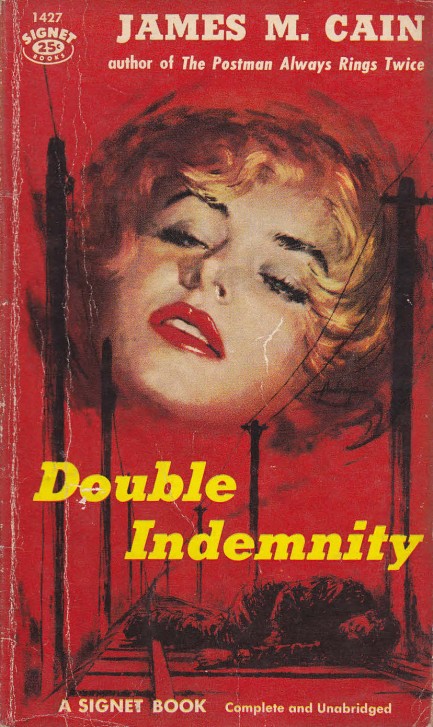

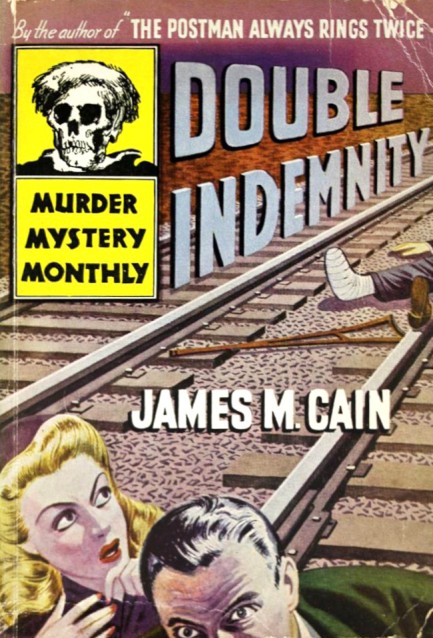

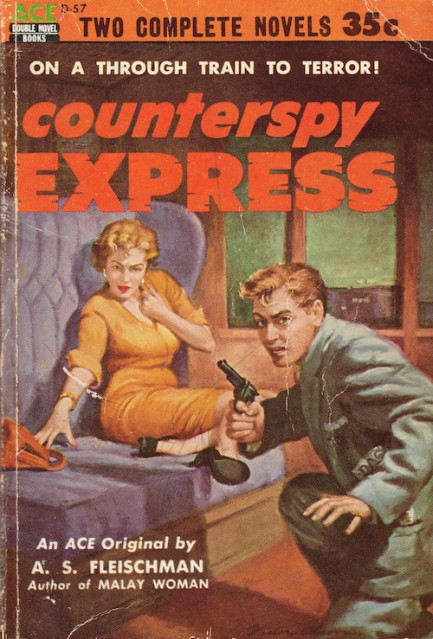

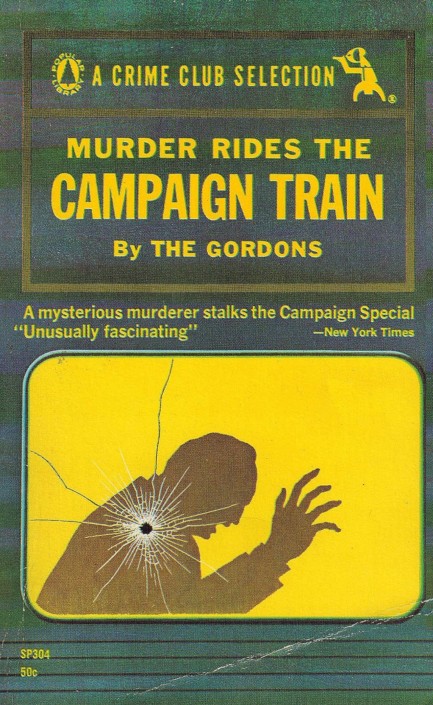

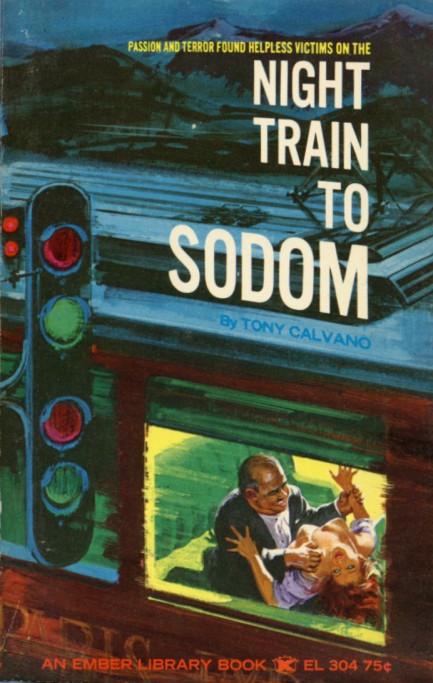

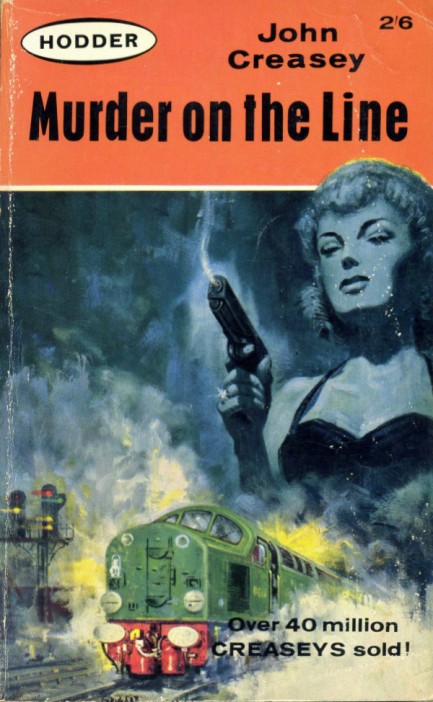

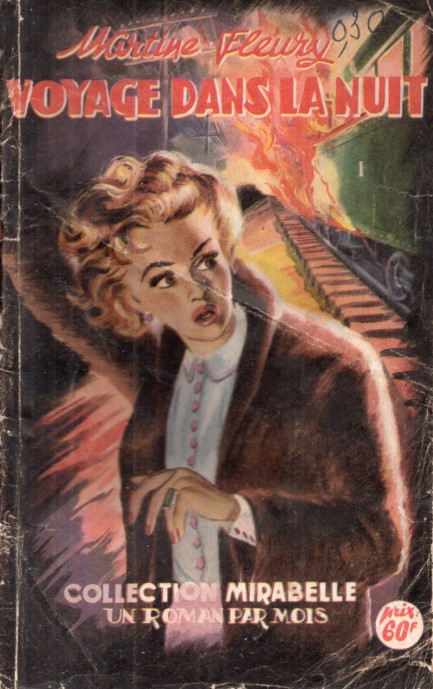

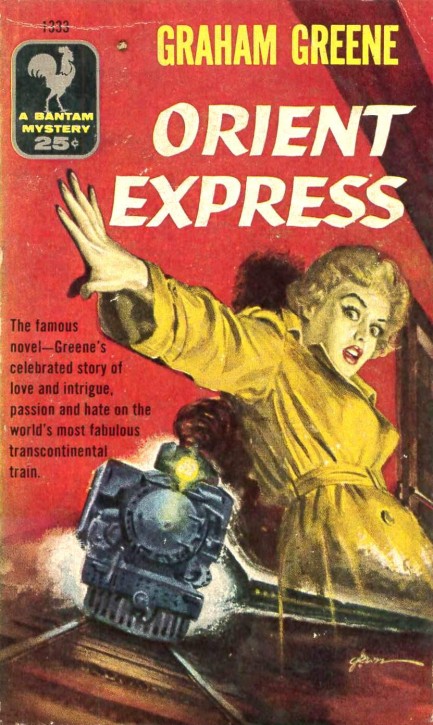

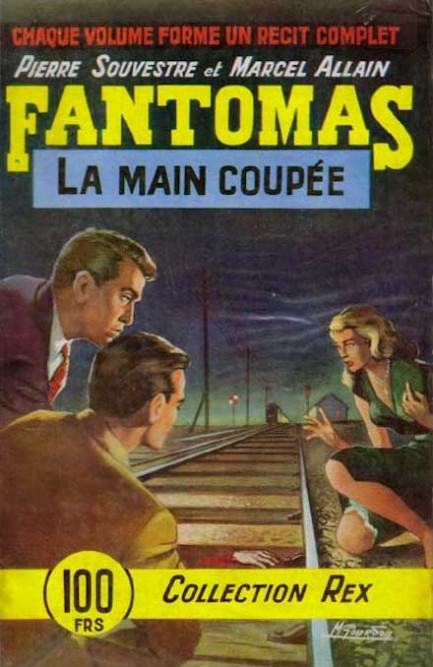

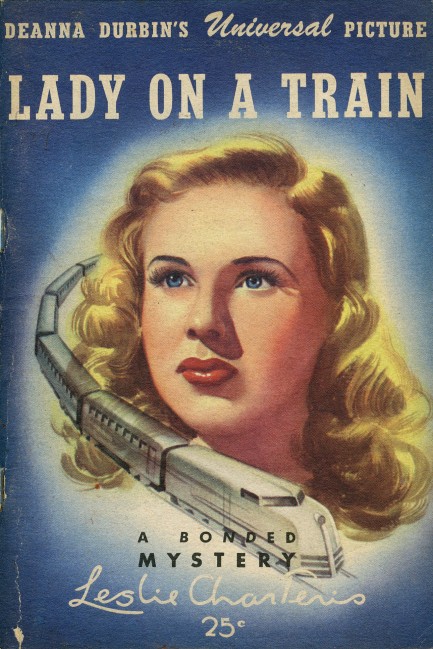

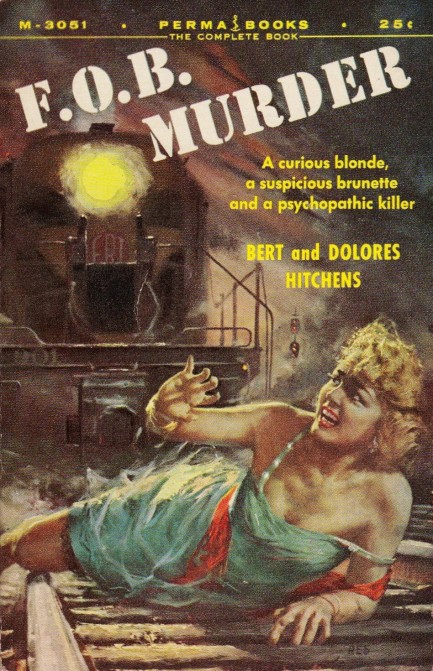

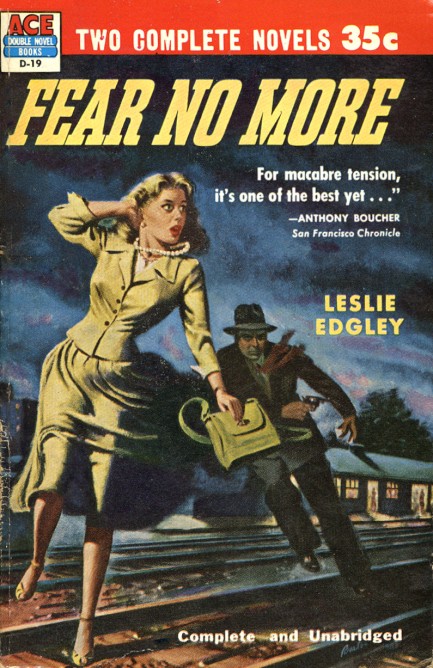

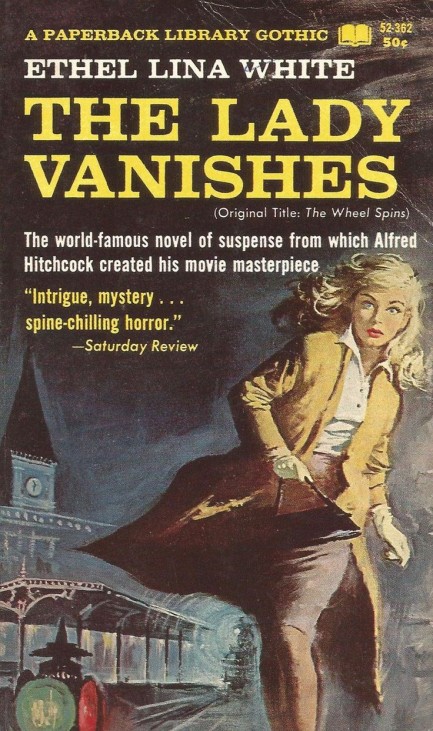

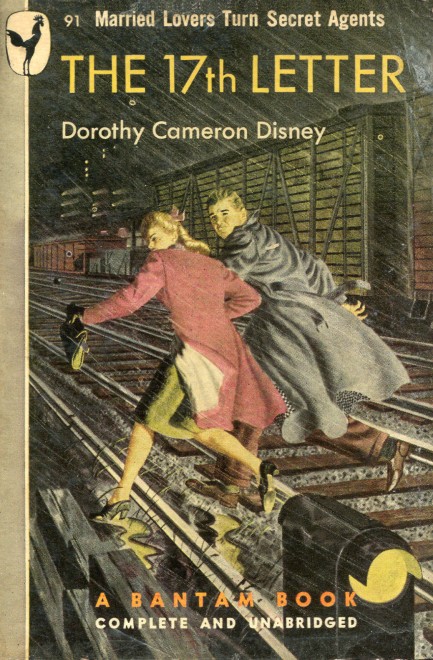

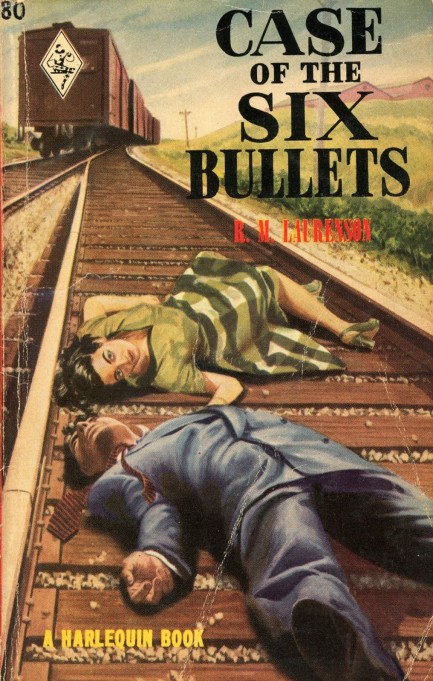

In pulp you're always on the wrong side of the tracks.

We're train travelers. We love going places by that method. It's one of the perks of living in Europe. Therefore we have another cover collection for you today, one we've had in mind for a while. Many pulp and genre novels prominently feature trains. Normal people see them as romantic, but authors see their sinister flipside. Secrets, seclusion, and an inability to escape can be what trains are about. Above and below we've put together a small sampling of covers along those lines. If we desired, we could create a similar collection of magazine train covers that easily would total more than a hundred scans. There were such publications as Railroad Stories, Railroad Man's Magazine, Railroad, and all were published for years. But we're interested, as usual, in book covers. Apart from those here, we've already posted other train covers at this link, this one, this one, and this one. Safe travels.

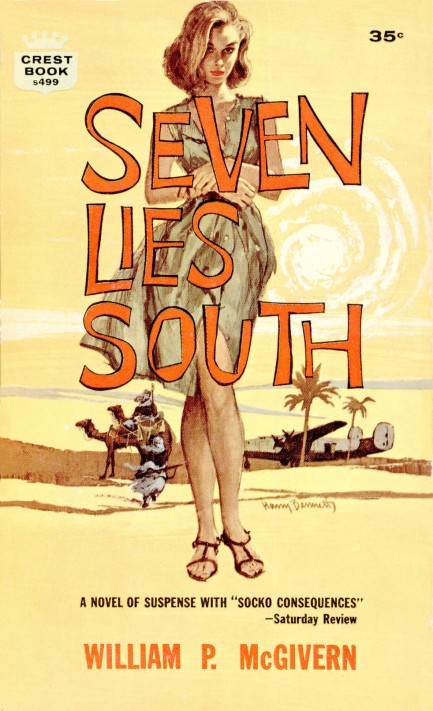

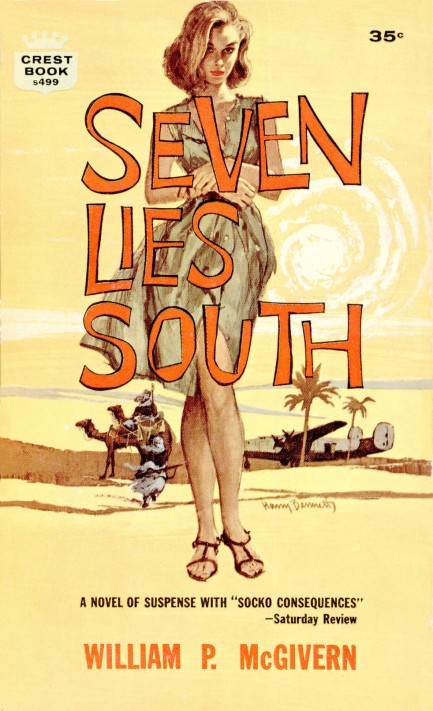

I know these regional airports lack the usual amenities, but a shuttle to the terminal sure would be nice.

We've mentioned before that we like to read books about places we've been, but we had no idea the 1960 thriller Seven Lies South was set in Spain and Morocco. We impulse-bought this 1962 Crest edition after seeing William P. McGivern's name and taking in the striking Harry Bennett cover art featuring a woman, an aircraft, two bedouins, and their camels. McGivern wrote the excellent 1961 juvenile delinquent thriller Savage Streets, so that was all we needed to know. We found out in the first page that the setting, as the story opened, was Malaga, Spain, and went, “Oh, okay—even better.”

The book stars Mike Beecher, a former bomber pilot, now in his late thirties and doing a belated Lost Generation bit—idleness, parties, a rotating cast of acquaintances, and a lot of solitary reflection in a foreign land. His Sun Also Rises-style fatalism is a little tedious, in our view. After all, he was never wounded in the sex organs like Jake Barnes, and if one's naughty bits function, there's always reason to smile. In any case, one day he meets a beautiful young woman named Laura Meadows, who embodies his dissatisfaction:

She symbolized everything that was unobtainable, beyond his reach; the rosy and prosperous life of America, with the tides of success sweeping everyone on to fine, fat futures.

But not everyone, of course. Entire ethnicities were excluded from that sweeping tide of success. Things are unobtainable for Beecher, but only because he's made a choice to reject them. What a luxury, to reject something, then bemoan what one “can't” have, when many people really can't have it. It's not a flaw in the book, so much as a cultural blind spot—perhaps deliberately inserted by McGivern, who was generally insightful about such issues. You have to sort of smile at Beecher's inability to appreciate being reasonably young, healthy, and knocking around the south of Spain drinking wine. Not everyone gets to do that. That's exactly what we do, and we appreciate it every day.

Beecher is coerced into helping to steal a plane headed for Morocco, but the mission goes wildly sideways, which unexpectedly mutates the narrative into a desert survival adventure. In order to set up and progress through this section, McGivern has his characters sometimes undertake actions that don't exactly resound with logic, but even so the book is good. McGivern can really write, even when it verges on the preposterous. He was more at home in the suburbs of Savage Streets, but he navigates the Spain and Morocco of Seven Lies South deftly enough. We have no hesitation about trying him again.

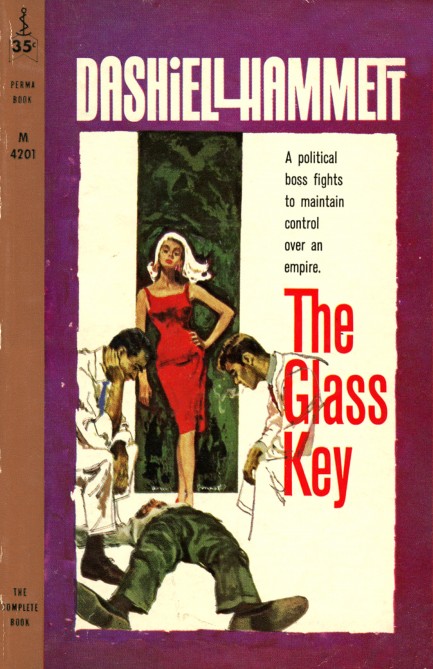

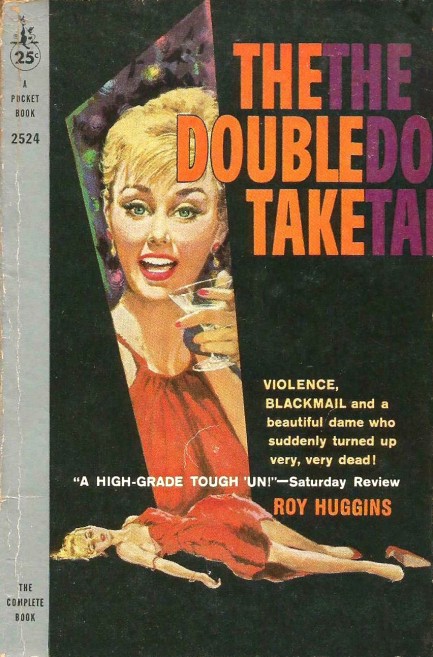

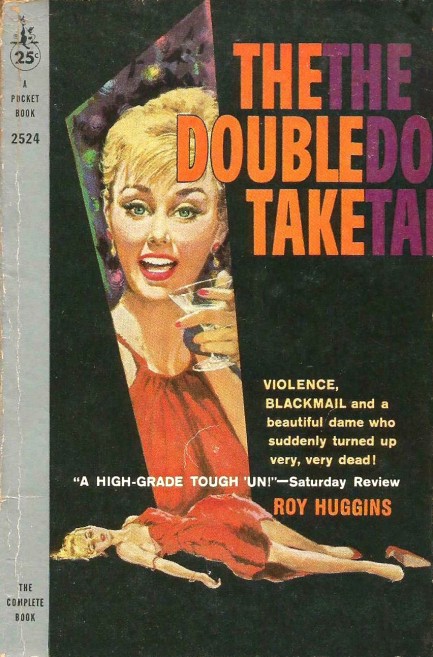

That second round of drinks is always murder.

This Pocket edition of Roy Huggins' detective mystery The Double Take is from 1959 and the art is by Harry Bennett. Huggins tells the story of a man who wants to dig into his wife's history and hires private dick Stu Bailey for the job. Bailey learns that the wife has been hiding for a long time. She's overweight now, but gained the pounds as a disguise. She'd also gotten married as a disguise, attended college and joined a sorority as a disguise, dyed her hair as disguise, changed her name as a disguise, and of course changed her city as a disguise. Somewhere way back before she was a plump wife with a suspicious husband she was a showgirl who called herself Gloria Gay. Bailey discovers all that, but the elusive question is why she's hiding in the first place.

Huggins probably should have done a bit better here. The concept is rich—a woman who essentially goes into hiding inside her own body by eating herself into a disguise. But he doesn't take advantage of the idea. Also, the second third of the book feels padded. That could have been shortened and the multi-twist final act would have been better for it. We did like those twists, though, and the L.A. setting was well rendered. It brought back memories from some wild years we spent running around Tinseltown. But in the end The Double Take was a middling time eater, and with time so precious, it isn't one we'd recommend dashing out to buy—or download, or whatever. Huggins has a Stu Bailey anthology called 77 Sunset Strip, and for the title alone we'll read that, and be hoping for something a bit better.

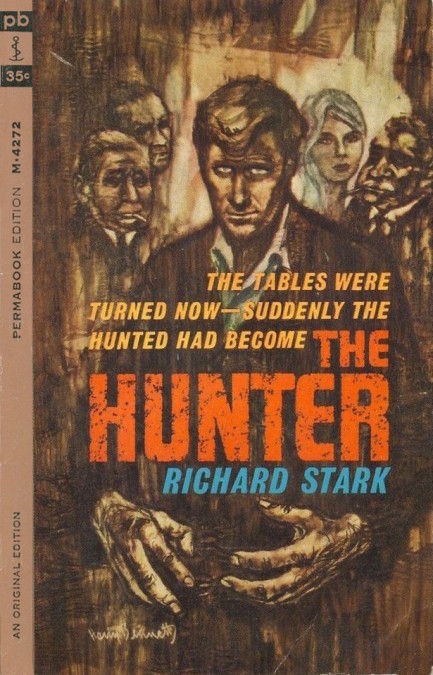

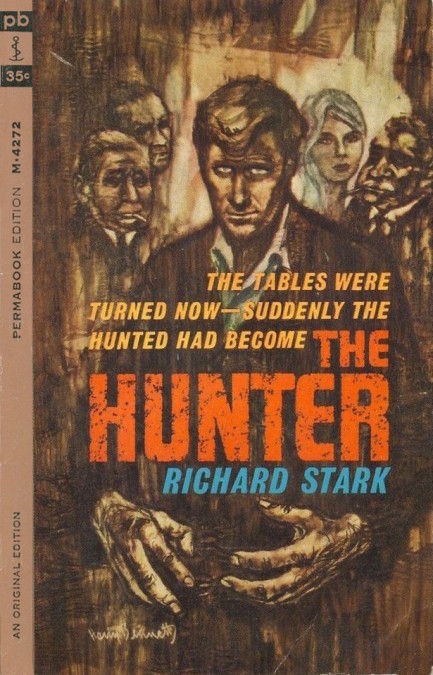

To a true hunter everyone is prey.

Richard Stark's, aka Donald E. Westlake's The Hunter, which was also published as Point Blank, is a landmark in crime literature, a precursor to characters like Jack Reacher. The standout qualities of this novel are its brutality and its smash cuts from set-piece to set-piece. As an example of the former, the main character, named Parker, basically scares a woman into committing suicide, dumps her body in a park, and slashes her face post-mortem as a way of foiling police attempts at identification. The latter quality, the narrative's disorienting transitions, is exemplified by a chapter that ends with Parker's hands mid-murder around an enemy's throat, and the next opening with him sitting in another enemy's house, holding a gun on him as he walks through the door. Westlake stripped away every bit of transitional prose he could in order to create breakneck pacing and heightened menace. Parker is not only dangerous, but is also emotionally barren. He feels nothing beyond the need to best his rivals. Permanently. Westlake's publisher knew The Hunter was something special, and convinced him to turn what was supposed to be a stand-alone novel into a series. Twenty-four entries in that series speak to its success. This first of the lot is highly recommendable. It came from Perma Books in 1962, and the excellent cover art featuring Parker's lethally large hands is by Harry Bennett.

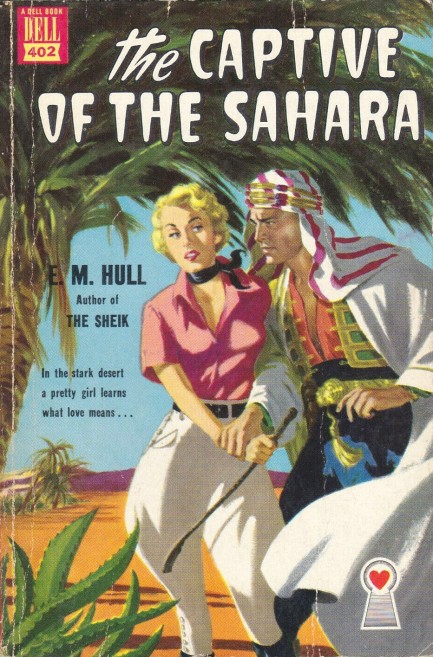

Crossing this desert we'll eventually be reduced to wearing filthy, sweat-crusted rags, but I'm glad we started out looking so fabulous.

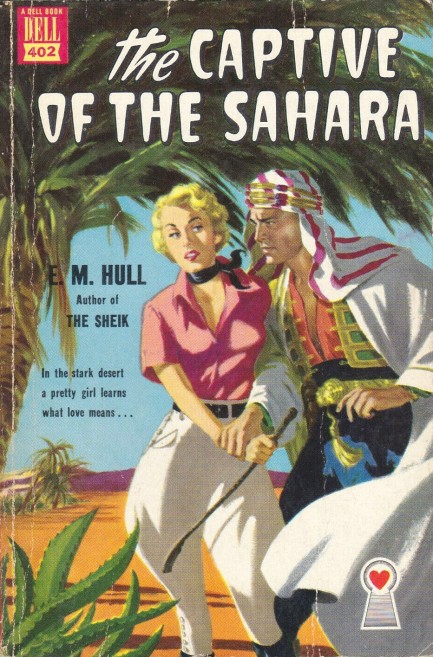

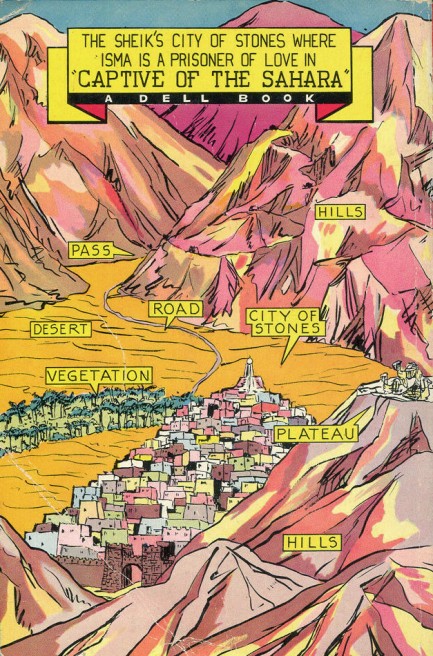

The pretty Harry Bennett cover art on this paperback won us over. Plus we wanted to read something set in the Sahara. Our trip to Morocco incubated strong interest in vintage fiction set in the region. The Captive of the Sahara was written in 1939 originally, with this Dell edition coming in 1950. British author E.M. Hull—Edith Maud to her friends, we bet—conjures up a tale here that's pure Arabian Nights, one of those florid books filled with words like “insensibly,” and where women suffer from heaving breasts and quickening pulses. This was Hull's realm. She published other books with similar settings, including 1919's The Sheik, which became a motion picture starring Rudolph Valentino

In The Captive of the Sahara virginal one percenter Isma Crichton travels for the sake of adventure to the City of Stones, and there in the trackless Algerian desert lustful Sidi Said bin Aissa decides to make dessert of her. Full disclosure: we're too corrupted to really enjoy books that hint around sex with poetic language. We're pulp guys. We can't help wanting these pale, trembling flowers to get properly laid, three or four detailed times, but that isn't Edith Maud's writerly plan. What happens is bin Aissa forces Isma to marry him, and a battle of wills follows as he tries to convince and/or bully her into relinqushing what he feels is rightfully his—her vagina.

Under these circumstances we were not keen to see Isma laid, properly or any other way. And that's effective writing for you. We had sneered through most of the book but now were rooting for Isma to escape her desert prison and return to dashing David—a childhood friend whose confession of love was the original trigger for her fearful (did we mention that virgin thing?) departure and eventual trip to the City of Stones. We have to give Edith Maud credit—she sucked us into to this tale, and we liked it in most parts, but we certainly shan't (see her influence?) be recommending it. It's overwrought, often silly, and at times viciously racist. But hey, if you're looking for a literary adventure-romance, this might be it.

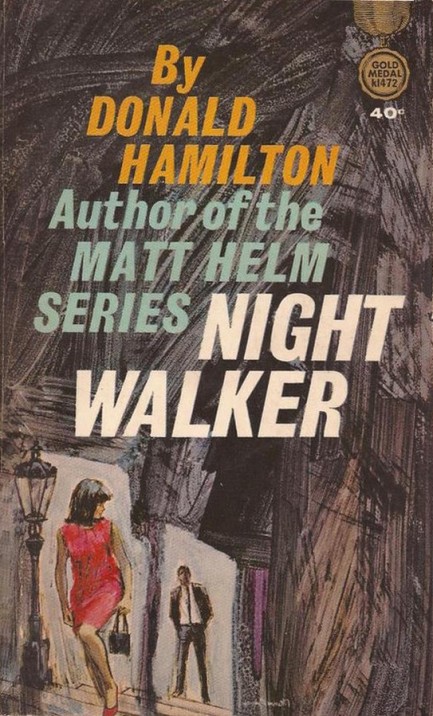

I go out walkin'... after midnight... out in the moonlight...

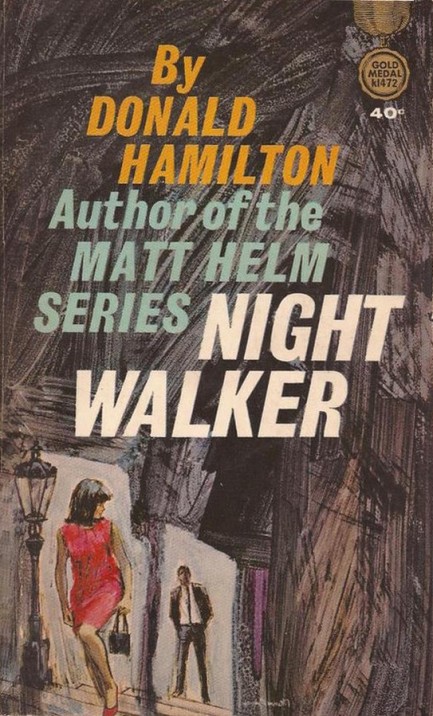

Crime writers all face the same task of dumping their heroes into hot water in new and interesting ways. In Night Walker Donald Hamilton shoves his protagonist into a bizarre situation and it all begins with him merely hitchhiking after dark. The next thing he knows he's hurt, housebound, and forced to assume a dead man's identity. If he doesn't continue the charade serious consequences could result, with prison being the least of them. But of course, as in any decent thriller, there's always the promise of great rewards, in this case the dead man's beautiful wife Elizabeth, or possibly the dead man's young mistress Bonita. There's a funny line of dialogue in this one when a character refuses a cigarette:

“Don't take it out on Philip Morris. He hasn't done anything to you.”

Ah, the 1950s, when men were men and cigarettes weren't coffin nails. And another staple of 1950s genre fiction is commie hysteria, also a major component of this book. But that's fine—every literary era has its archetypal villains. The book's fatal flaw is that the latter portion contains long monologues of the bad guy explaining his evil plot, due to the fact that Hamilton hasn't constructed the narrative for the hero to suss it out for himself. Tedious doesn't even begin to describe this sort of writing. Overall Night Walker is middling work from Hamilton, passable in the first half, but a bit taxing in the second. Good thing this 1964 edition from Fawcett's Gold Medal was cheap. And the cover art is nice. It's by Harry Bennett.

|

|

The headlines that mattered yesteryear.

1945—Mussolini Is Arrested

Italian dictator Benito Mussolini, his mistress Clara Petacci, and fifteen supporters are arrested by Italian partisans in Dongo, Italy while attempting to escape the region in the wake of the collapse of Mussolini's fascist government. The next day, Mussolini and his mistress are both executed, along with most of the members of their group. Their bodies are then trucked to Milan where they are hung upside down on meathooks from the roof of a gas station, then spat upon and stoned until they are unrecognizable. 1933—The Gestapo Is Formed

The Geheime Staatspolizei, aka Gestapo, the official secret police force of Nazi Germany, is established. It begins under the administration of SS leader Heinrich Himmler in his position as Chief of German Police, but by 1939 is administered by the Reichssicherheitshauptamt, or Reich Main Security Office, and is a feared entity in every corner of Germany and beyond. 1937—Guernica Is Bombed

In Spain during the Spanish Civil War, the Basque town of Guernica is bombed by the German Luftwaffe, resulting in widespread destruction and casualties. The Basque government reports 1,654 people killed, while later research suggests far fewer deaths, but regardless, Guernica is viewed as an example of terror bombing and other countries learn that Nazi Germany is committed to that tactic. The bombing also becomes inspiration for Pablo Picasso, resulting in a protest painting that is not only his most famous work, but one the most important pieces of art ever produced. 1939—Batman Debuts

In Detective Comics #27, DC Comics publishes its second major superhero, Batman, who becomes one of the most popular comic book characters of all time, and then a popular camp television series starring Adam West, and lastly a multi-million dollar movie franchise starring Michael Keaton, then George Clooney, and finally Christian Bale. 1953—Crick and Watson Publish DNA Results

British scientists James D Watson and Francis Crick publish an article detailing their discovery of the existence and structure of deoxyribonucleic acid, or DNA, in Nature magazine. Their findings answer one of the oldest and most fundamental questions of biology, that of how living things reproduce themselves.

|

|

|

It's easy. We have an uploader that makes it a snap. Use it to submit your art, text, header, and subhead. Your post can be funny, serious, or anything in between, as long as it's vintage pulp. You'll get a byline and experience the fleeting pride of free authorship. We'll edit your post for typos, but the rest is up to you. Click here to give us your best shot.

|

|