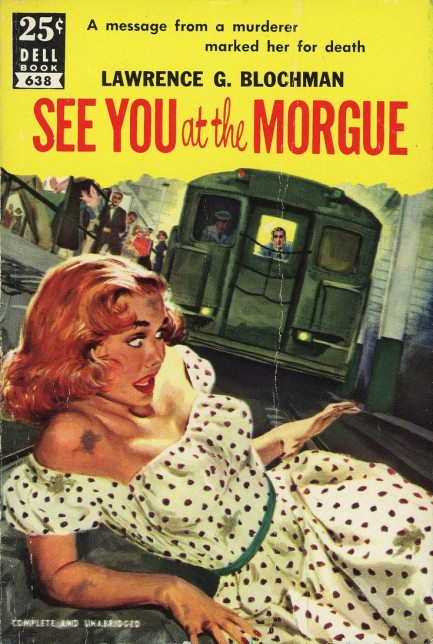

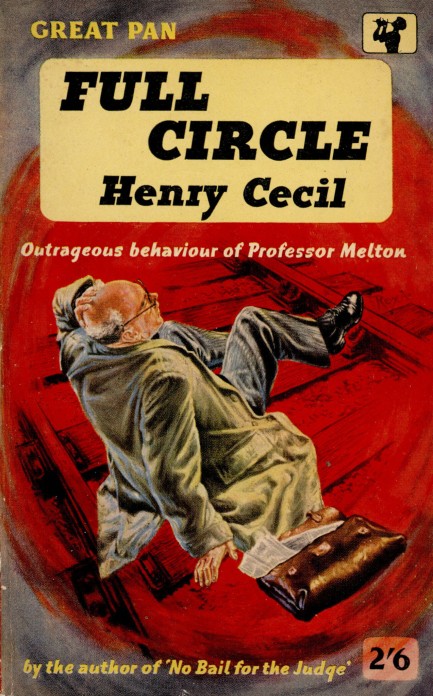

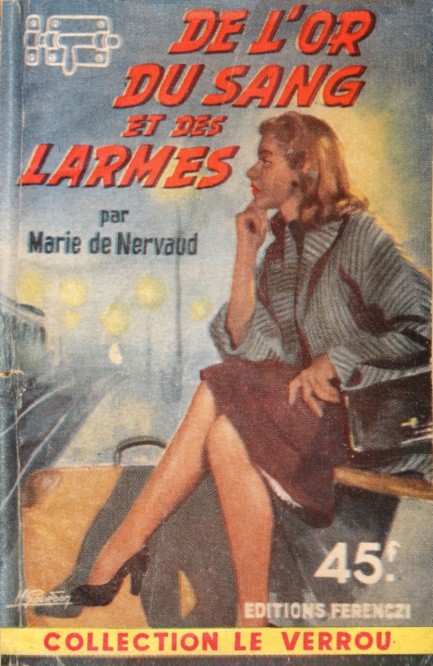

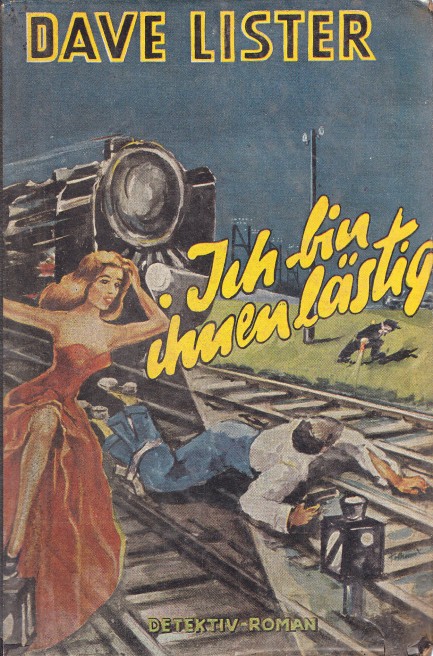

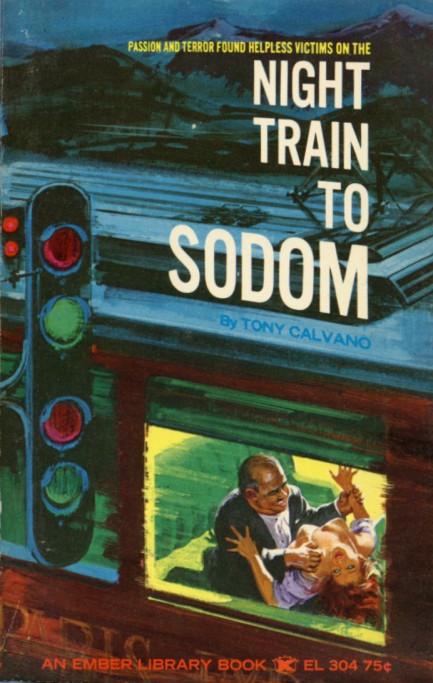

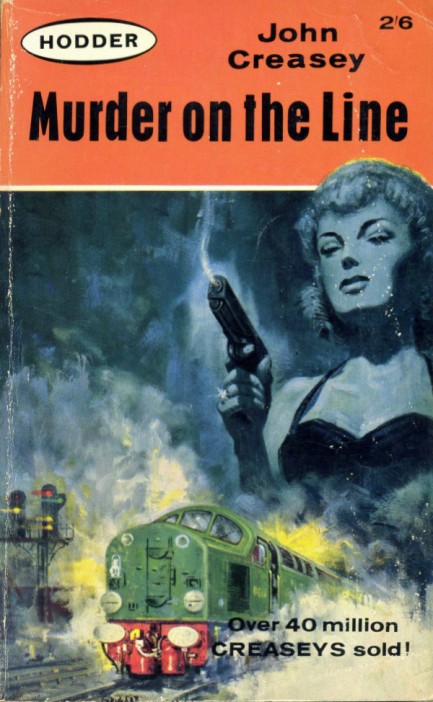

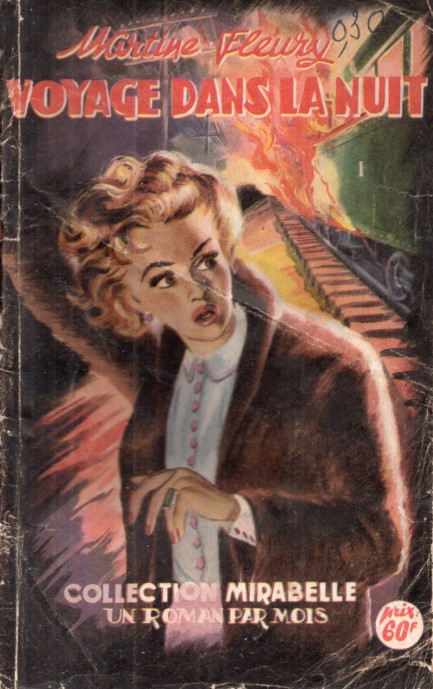

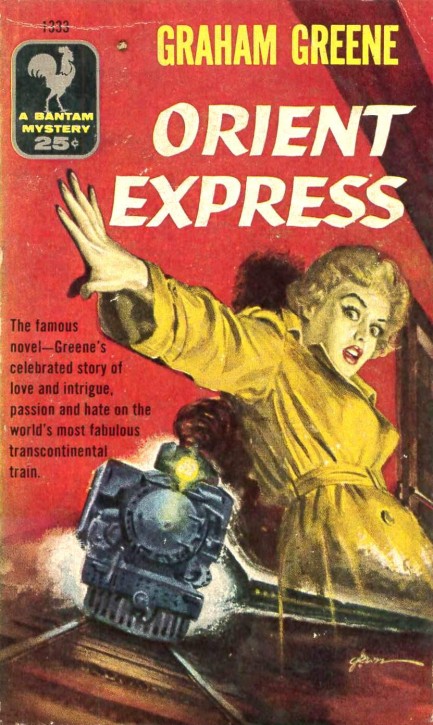

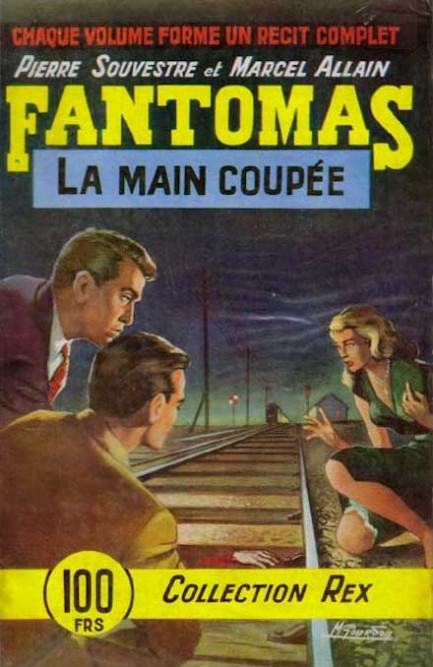

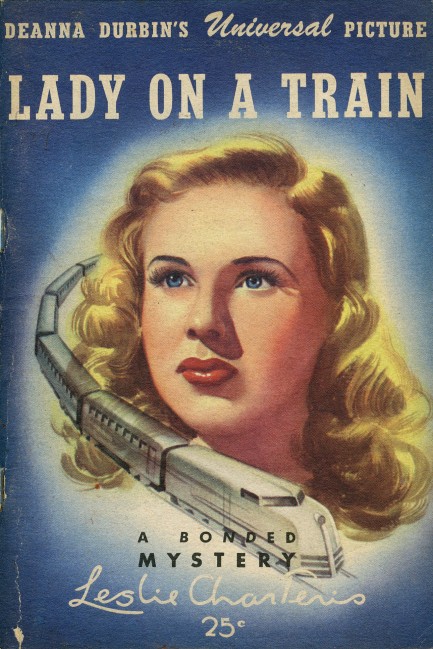

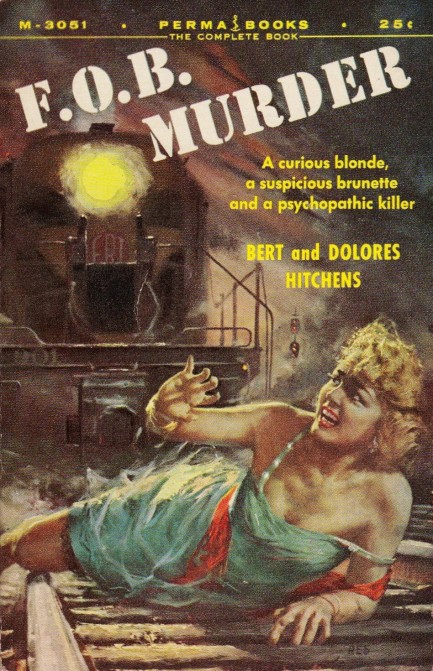

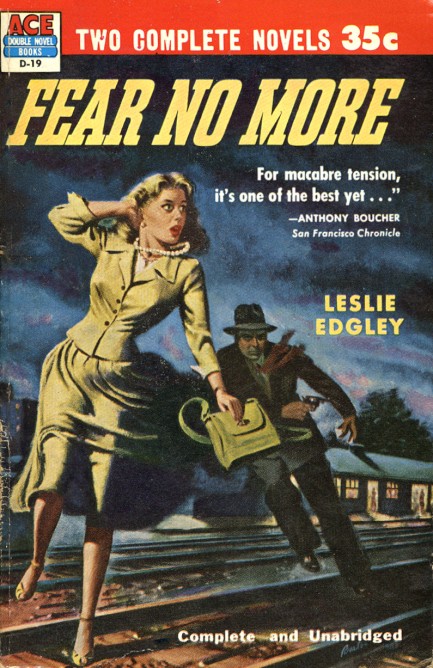

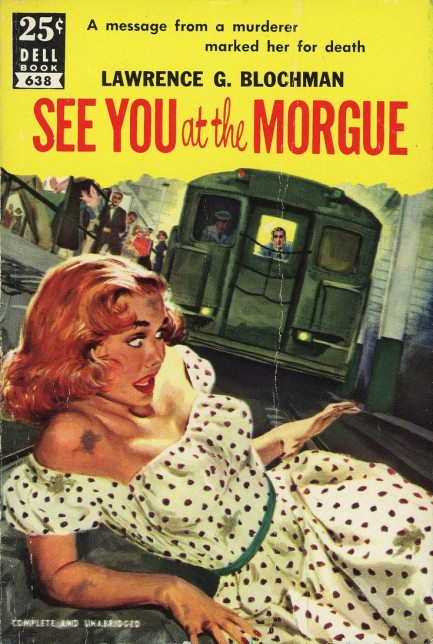

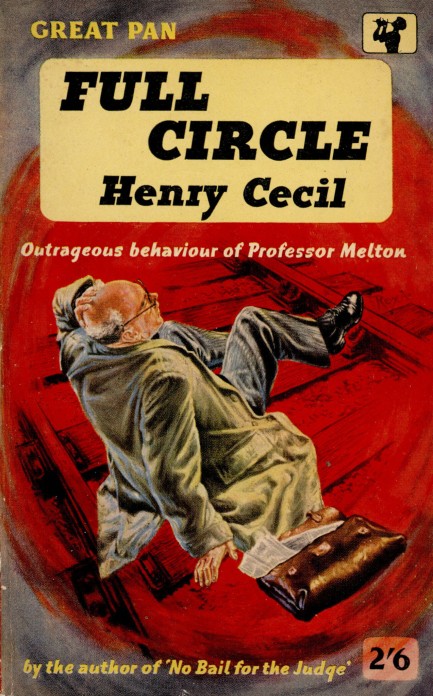

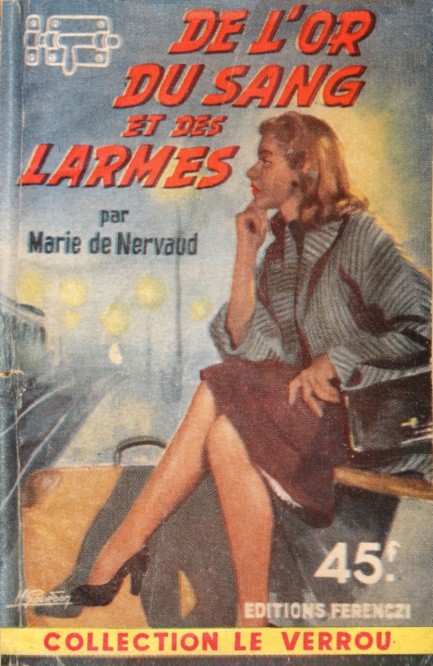

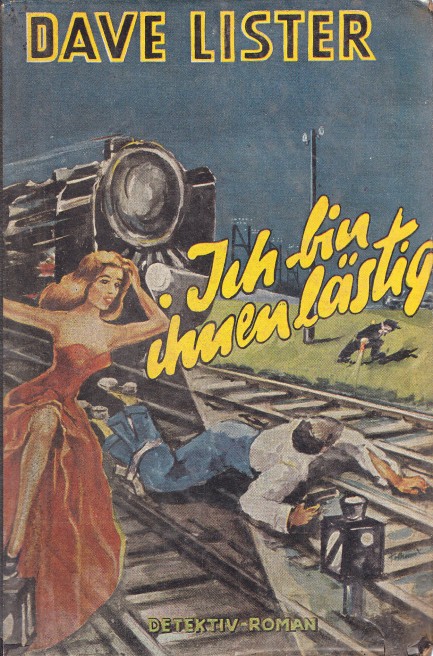

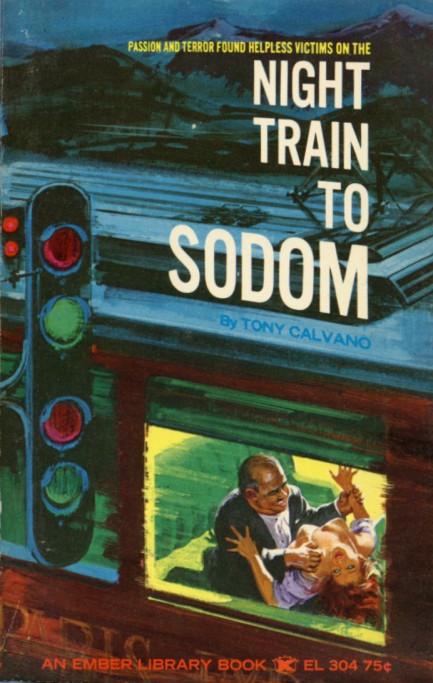

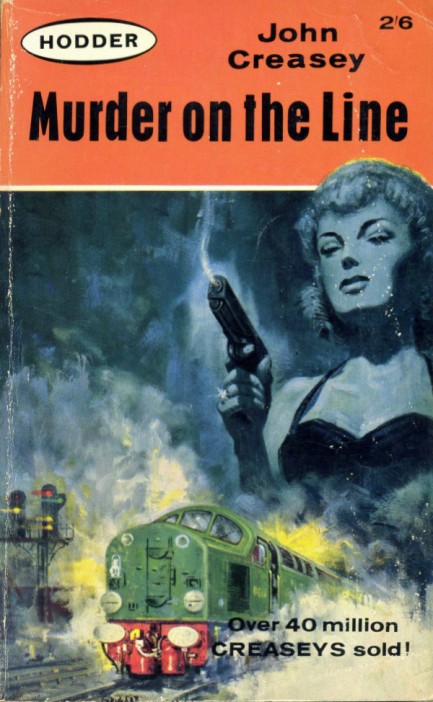

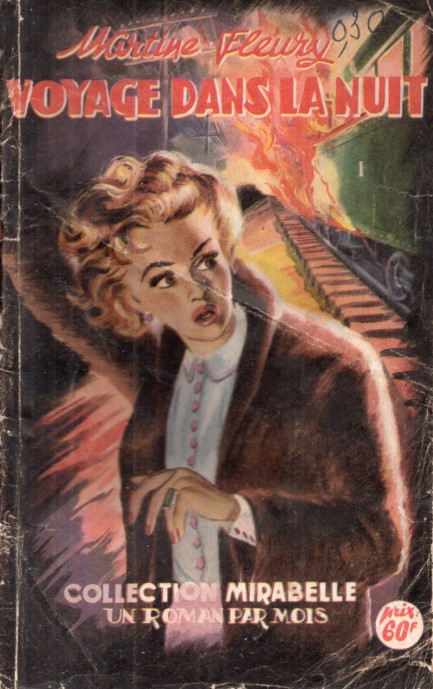

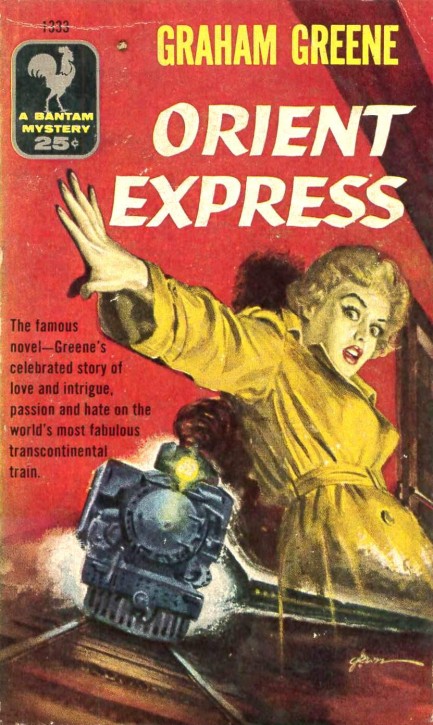

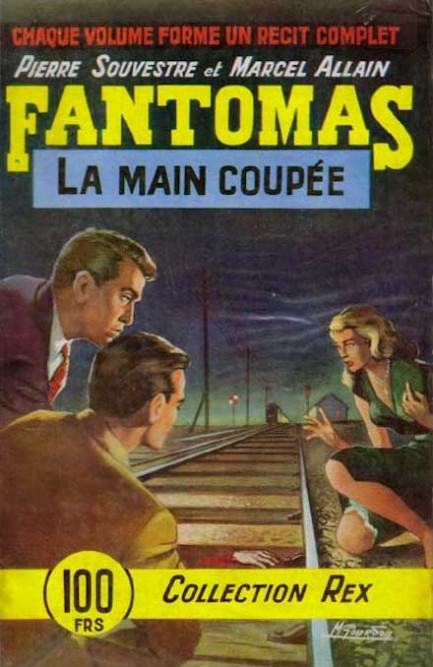

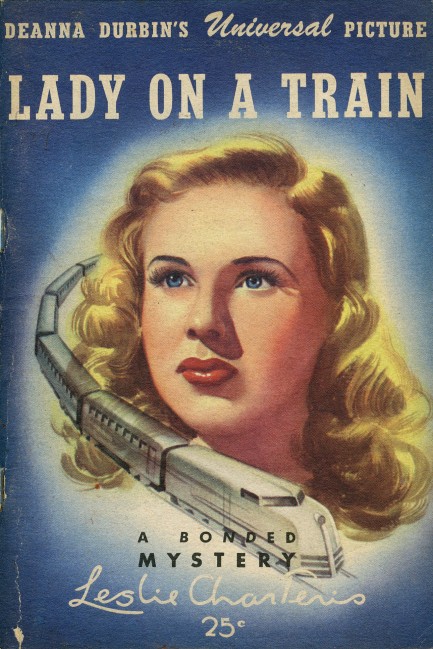

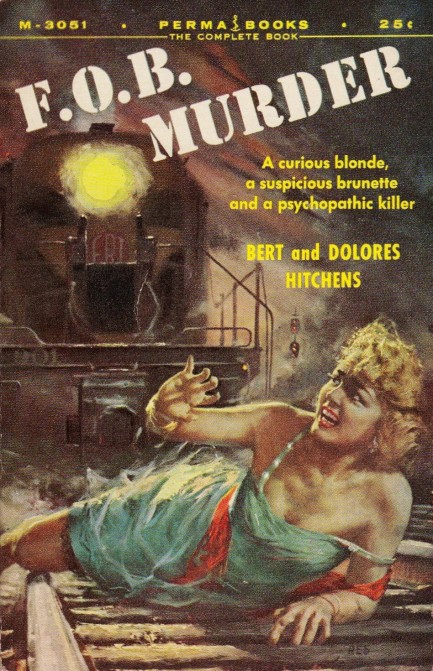

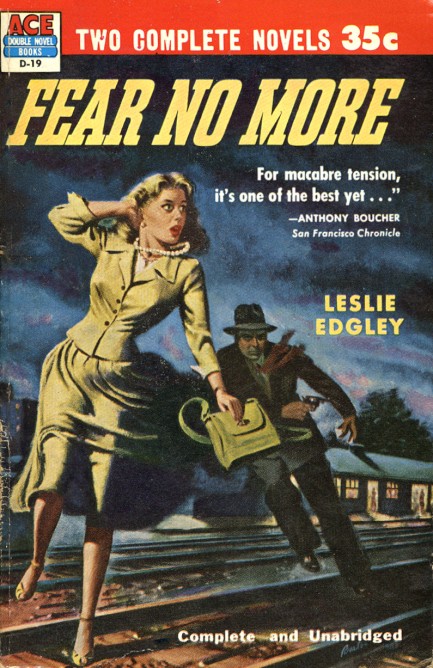

In pulp you're always on the wrong side of the tracks.

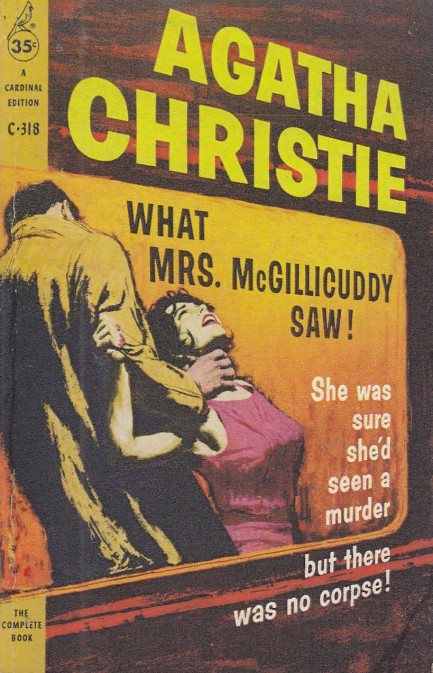

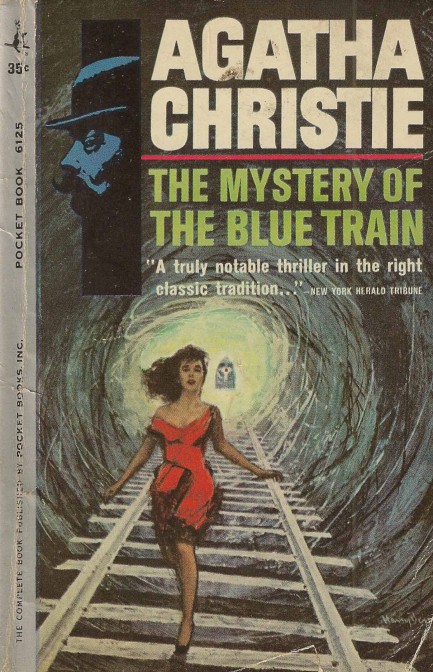

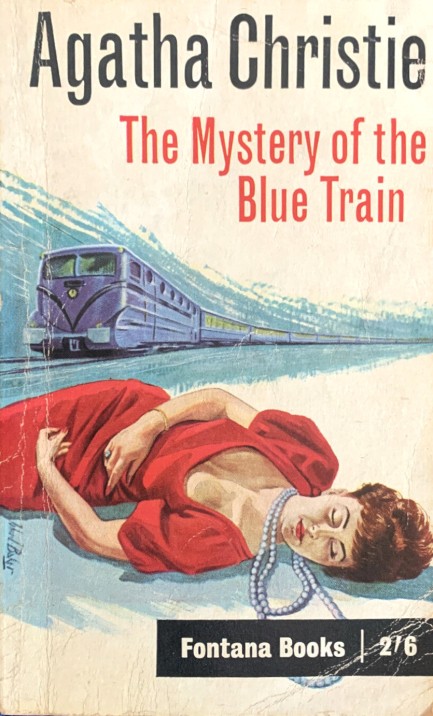

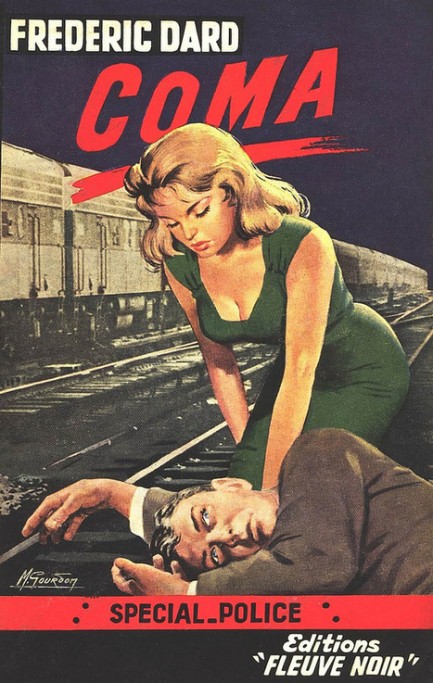

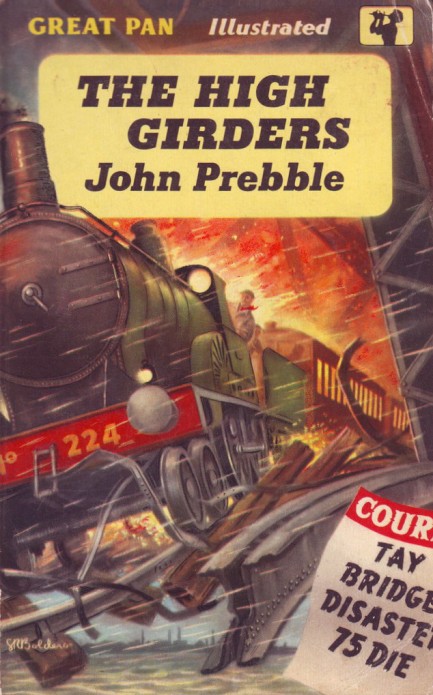

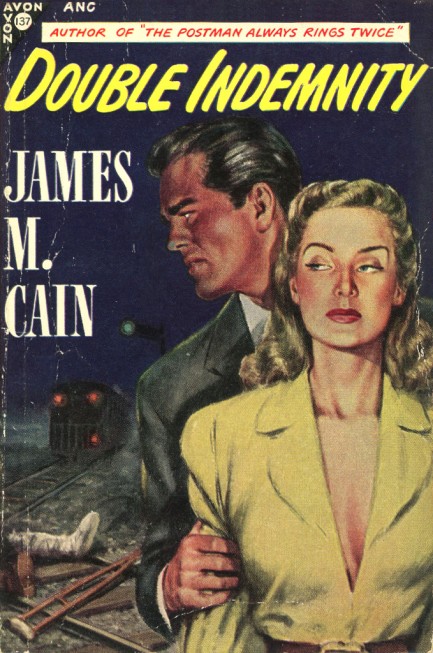

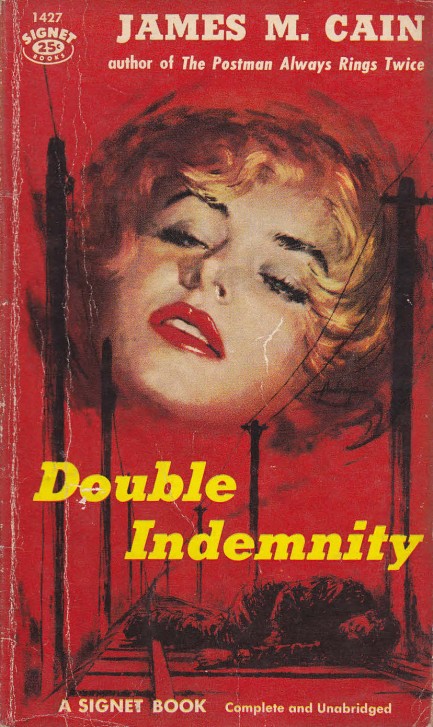

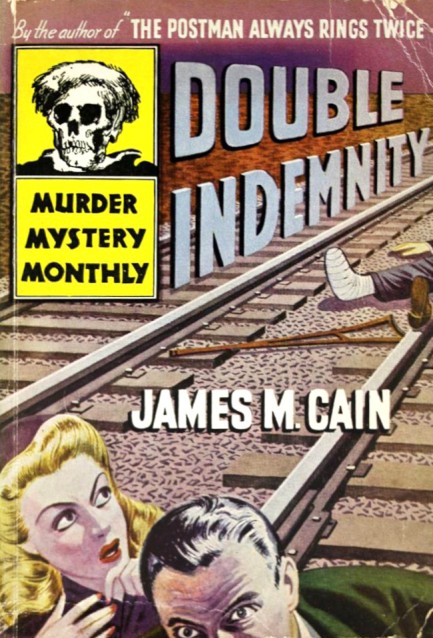

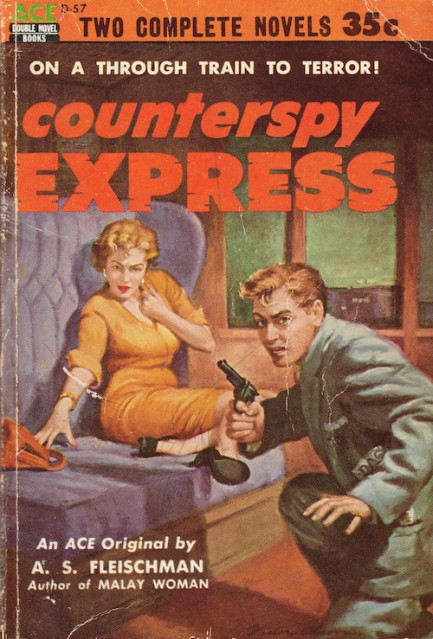

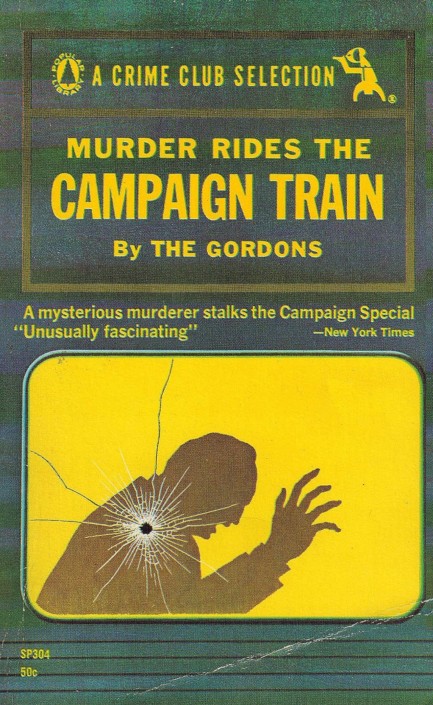

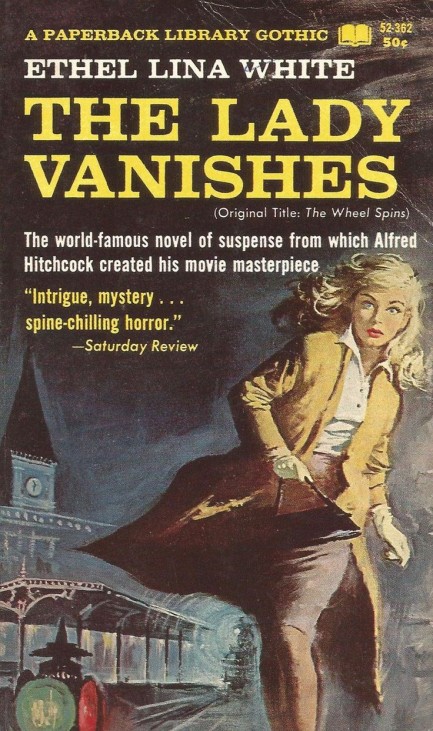

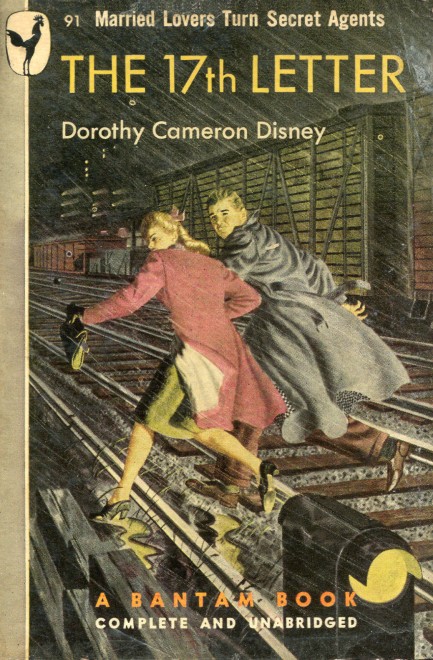

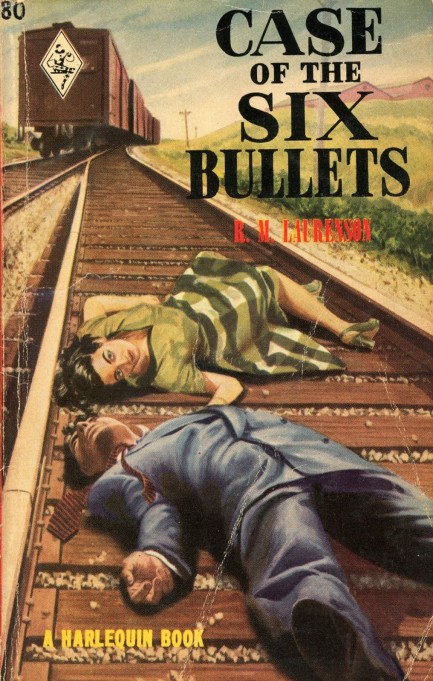

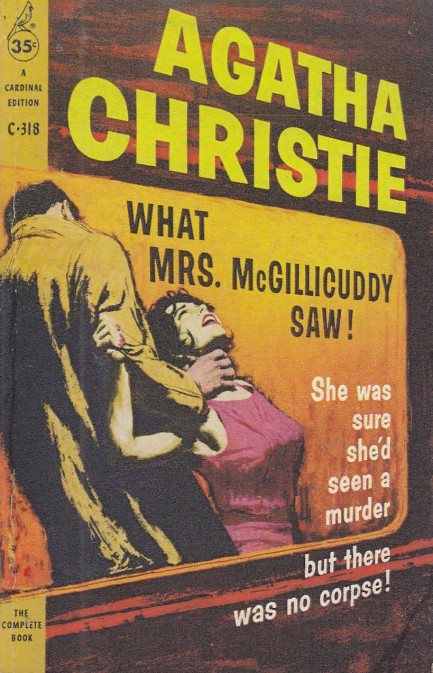

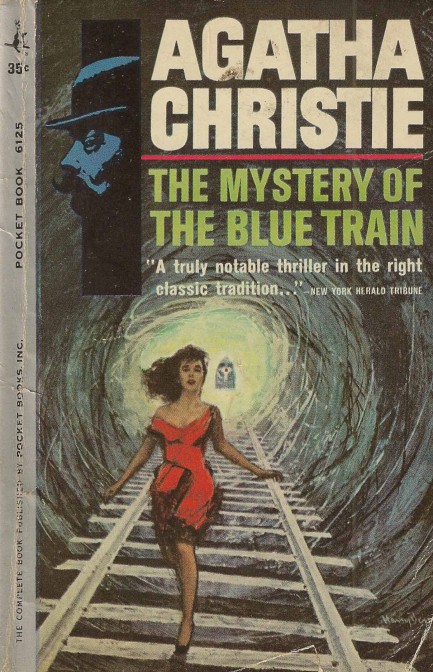

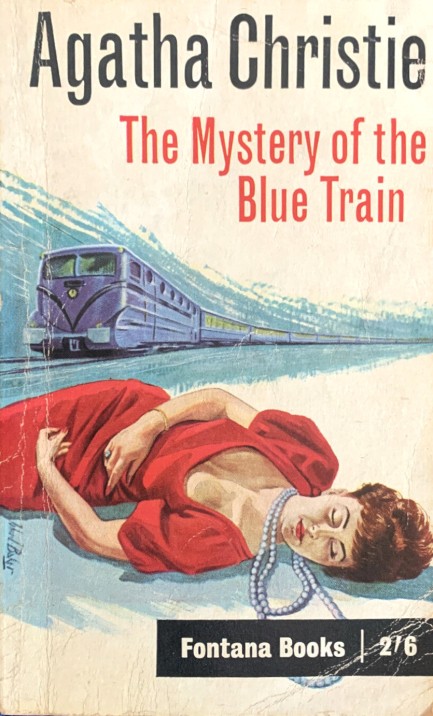

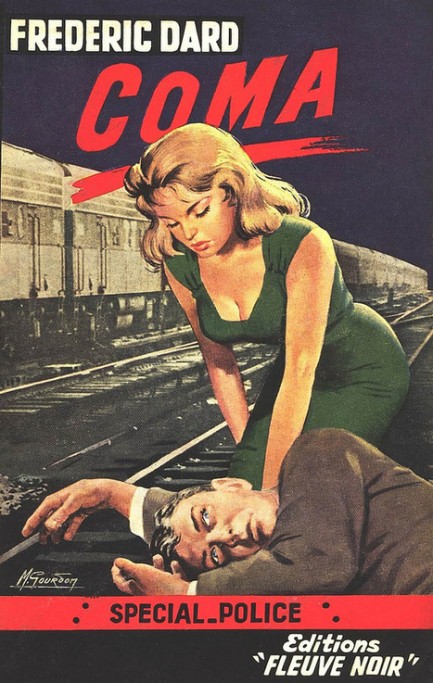

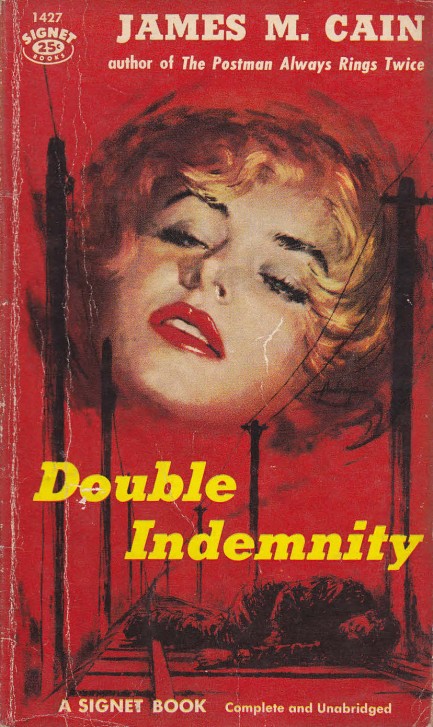

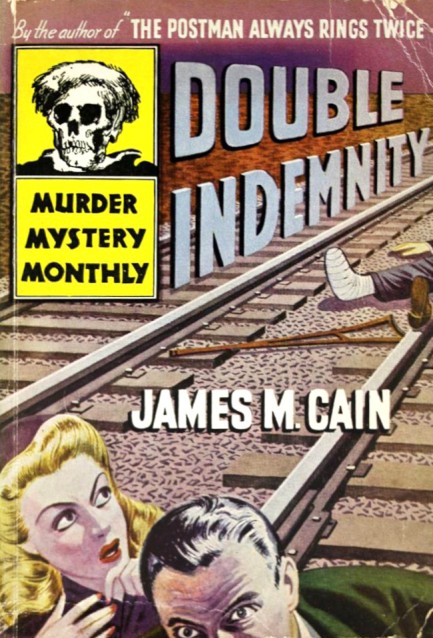

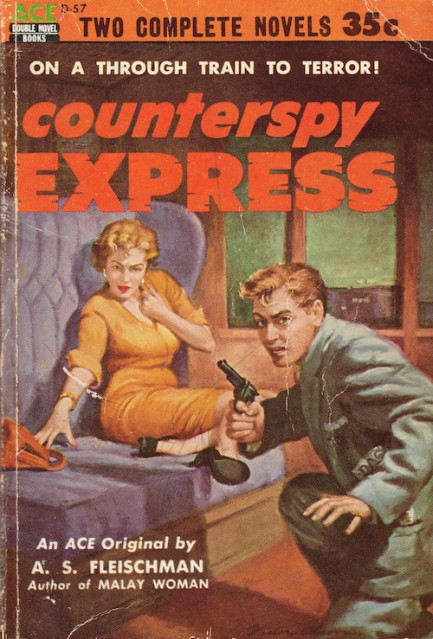

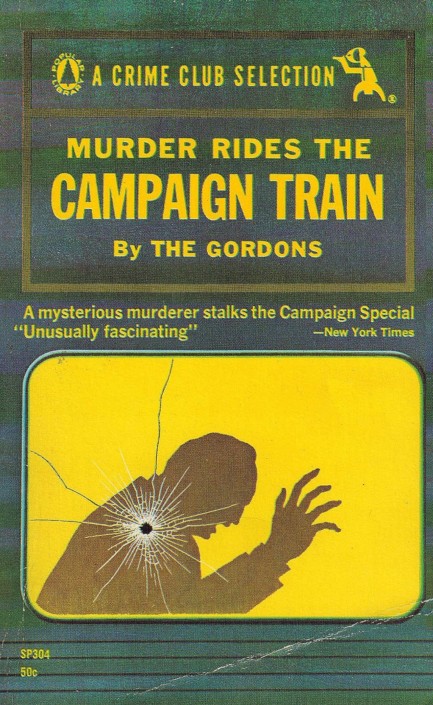

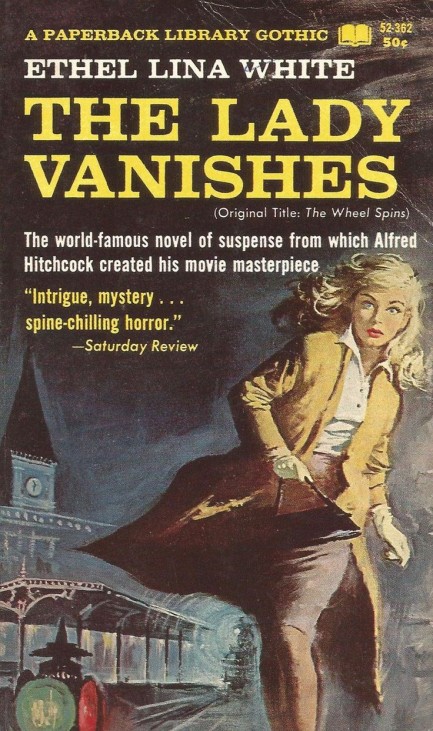

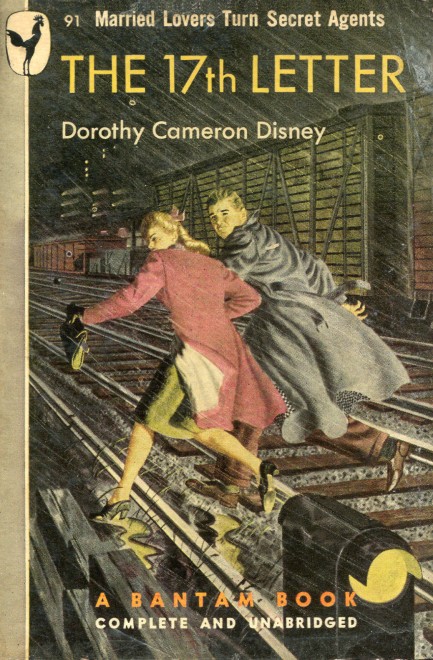

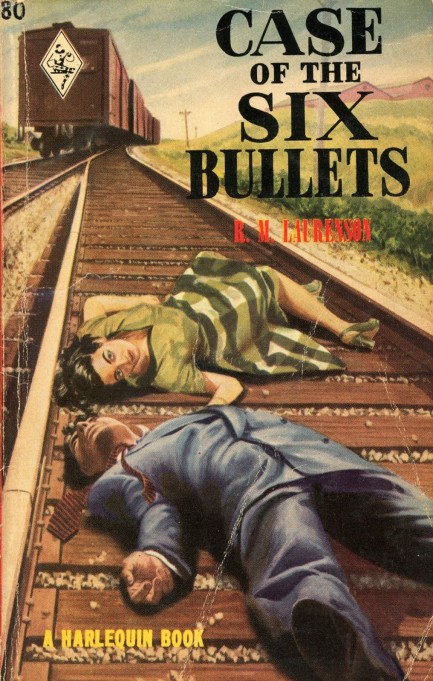

We're train travelers. We love going places by that method. It's one of the perks of living in Europe. Therefore we have another cover collection for you today, one we've had in mind for a while. Many pulp and genre novels prominently feature trains. Normal people see them as romantic, but authors see their sinister flipside. Secrets, seclusion, and an inability to escape can be what trains are about. Above and below we've put together a small sampling of covers along those lines. If we desired, we could create a similar collection of magazine train covers that easily would total more than a hundred scans. There were such publications as Railroad Stories, Railroad Man's Magazine, Railroad, and all were published for years. But we're interested, as usual, in book covers. Apart from those here, we've already posted other train covers at this link, this one, this one, and this one. Safe travels.

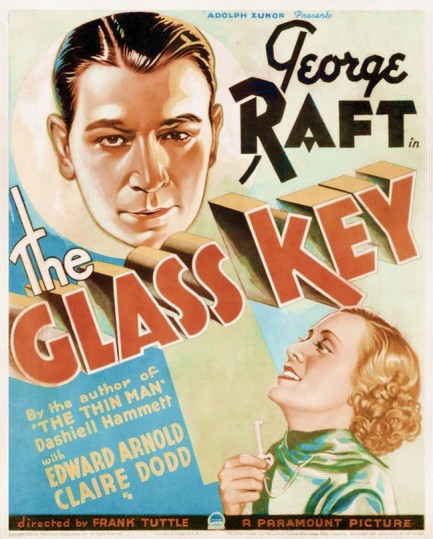

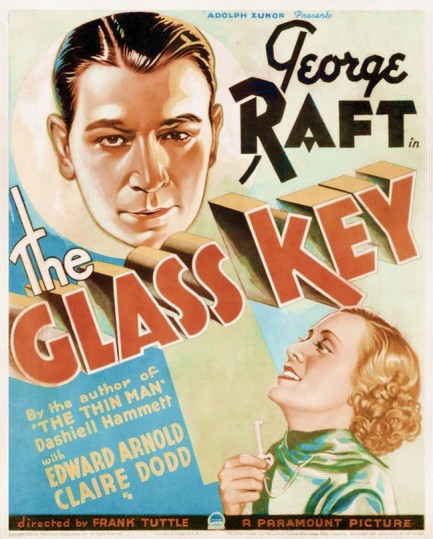

George Raft does the heavy lifting in 1935 crime thriller.

Is there any vintage movie star as overlooked these days as George Raft? The man was one of the top box office draws of the 1930s and had a string of hits through the 1940s and into the 1950s, including the 1959 smash Some Like It Hot. He was an ace stage dancer at the beginning of his career, but onscreen this natural athlete strikes many modern viewers as too dumpy for the tough guy roles he pioneered. Which makes it ironic that he was associated in real life with several gangsters, which led to him appearing in court, and in turn led to the public believing he was really living the thug life. Rather than hurting his popularity, the whiff of criminality made him more popular—something to keep in mind whenever some self-appointed sociologist slams kids for liking rappers.

Above you see a poster for one of Raft's biggest successes, the 1935 adaptation of Dashiell Hammett's novel The Glass Key. A 1942 version would also be a big hit for Alan Ladd and Veronica Lake, and the fact that it was rebooted just seven years after the original would seem to tell you plenty. But Raft's version isn't bad. We think it's simply a case of technical advances in the process of shooting films and the continuing popularity of Hammett making the property an attractive one to redo. Watching both movies back to back is a clinic in how quickly filmmaking advanced as the ’40s rolled around, particularly ideas around staging and editing action.

Even so, Raft made this earlier version of The Glass Key a hit by virtue of his star power, despite the fact that critics were not overly impressed with the film. No less a figure than Graham Greene said it was “unimaginatively gangster,” which is a curiously millennial turn-of-phrase. But Raft, playing the capable right hand man of a top underworld figure who's on the verge of open warfare with his enemies, doesn't deserve any of the blame. His hard boiled persona is the only reason this otherwise static film is worth watching. The Glass Key premiered in the U.S. today in 1935.

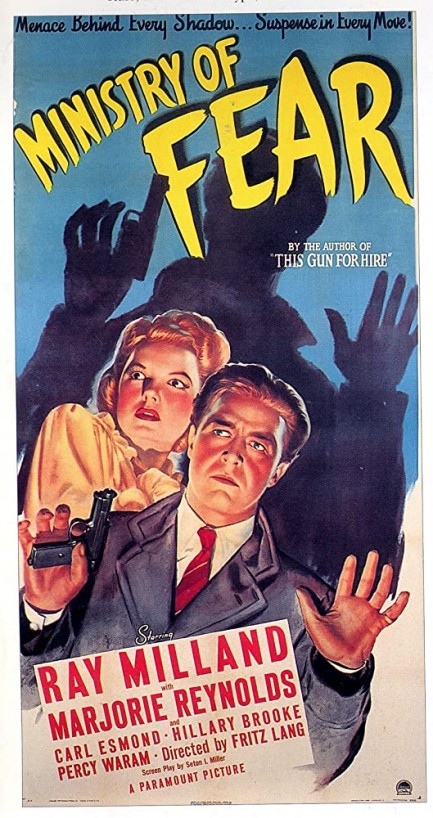

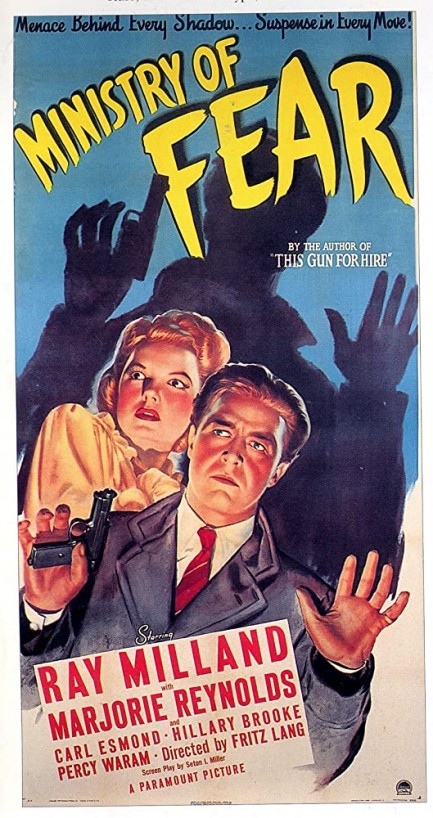

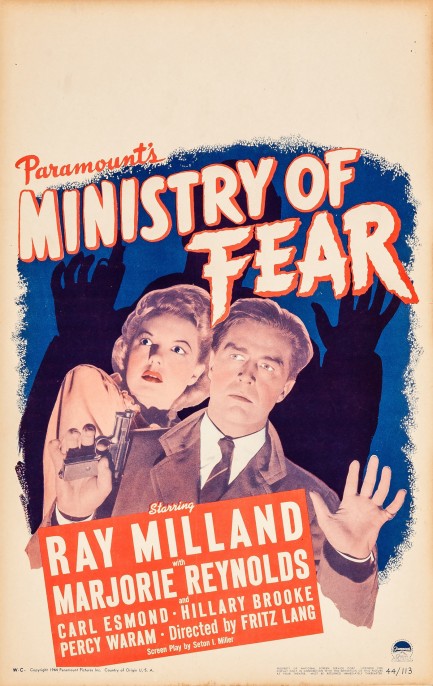

In the Ministry of Fear they bake better than they spy.

Fritz Lang was one of the most important directors of his era, both in his native Germany and in the U.S., and was a pioneer of the film noir form. Movies like Scarlet Street and especially The Big Heat are essential noir viewing. Ministry of Fear dates from a bit earlier and finds Lang saddled with what we consider to be a substandard script that through sheer artistry he makes into a watchable film. Ray Milland, Marjorie Reynolds, and Dan Duryea headline in a spy tale that revolves around Lang's favorite villains—the Nazis. Jewish and German, he left his homeland for Paris and beyond during the ascent of the Nazis during the 1930s, so the subject was personal for him, and was one he'd dealt with in previous films such as Cloak and Dagger and Hangmen Also Die.

In Ministry of Fear Milland plays a man who spends two years in a British asylum and is released at a time when World War II is raging and London is being bombed. He goes to a charity carnival and is enticed into guessing a cake's weight for a chance to win it, and because he's been given the correct answer by a fortuneteller, is victorious. But it's soon clear that the correct weight wasn't supposed to be given to him, and he isn't supposed to have won the cake. But he really wants it and resists attempts by the carny folks to take it back. He loses it during a train ride when a passenger beats the snot out of him for it, and at that point finally realizes the obvious—sweet though this confection may have been, it wasn't sought by various and sundry for its flavor, but because inside was something important. He wants answers, and he'll have to risk his neck to get them.

Generally with movies it's best to simply accept the premise, but there are limits. We were never clear on why it was necessary to put this important item in a cake. We understand subterfuge is involved in the spy game, but why not just hand the item over in an alley, or a pub bathroom, or a parked car? And if food must be involved, why a cake? Why not a haggis, or something else very few people want to just gobble up on the spot? A dried cod maybe. A blood sausage would have done. Plus they're easy to transport. You can just stick them in your pockets. And in a tight spot a whack across the nose with a blood sausage is far more effective than shoving cake in someone's mug. The cake gimmick was probably—strike that—certainly better explained in Graham Greene's source novel. We haven't read it but we're confident about that. It could have been Lang who screwed the pooch, but it was more likely Seton I. Miller. He was screenwriter as well as executive producer.

In any case Milland bumbles his way through a train trip, across a moor, in and out of a crazy séance, and into a maze of misdirection to the eventual revelation of what's inside the cake, but the whole time we kept thinking the movie should be called Ministry of Cut-Rate Spies. We don't mean to say it's a total loss. It isn't like the Eddie Izzard comedy routine, “Cake or Death.” You won't choose death over cake. But it's a pretty uninspiring flick. The old dramas that have survived have done so for a simple reason. Most of them are good. Ministry of Fear isn't bad. It's just meh. It's like a cake that fell—it's flat and dense, but teases you with how yummy it could have been. It premiered in England today in 1944.

Here, have your cake. And eat it too. Heh. Here, have your cake. And eat it too. Heh.

I prefer blood sausage for train trips, but I guess it's better for you I'm not shoving one of those in your face, eh? I prefer blood sausage for train trips, but I guess it's better for you I'm not shoving one of those in your face, eh?

Wow, you sort of... crush the shit out of your cake before eating it. Wow, you sort of... crush the shit out of your cake before eating it.

Have I been eating cake wrong the whole time I've been in England? Have I been eating cake wrong the whole time I've been in England?

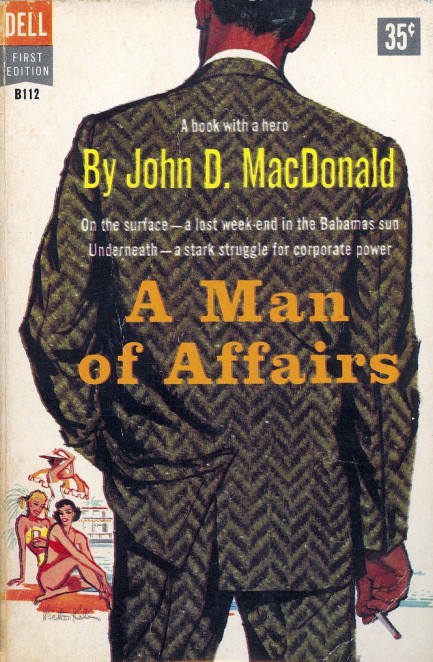

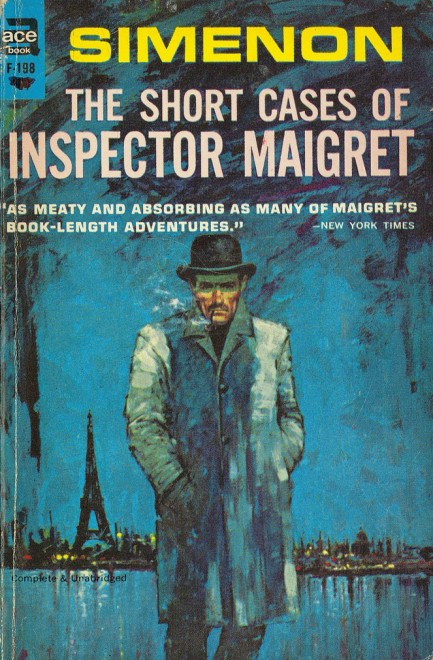

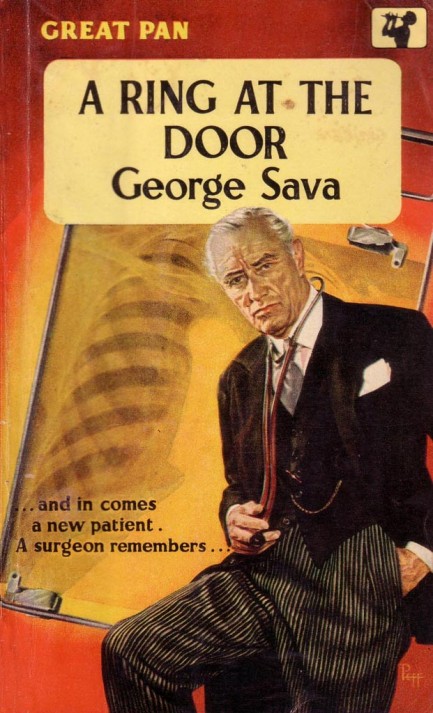

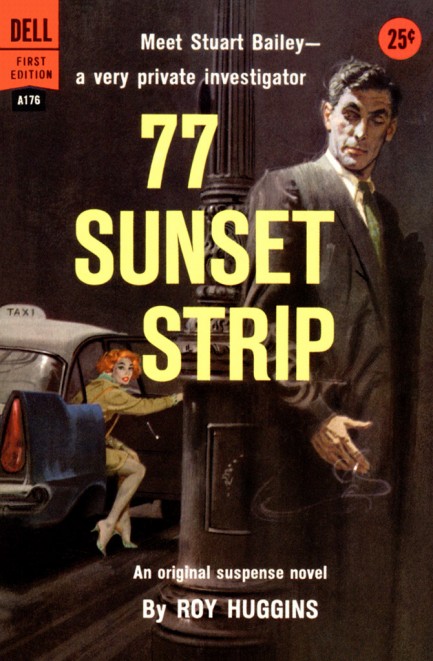

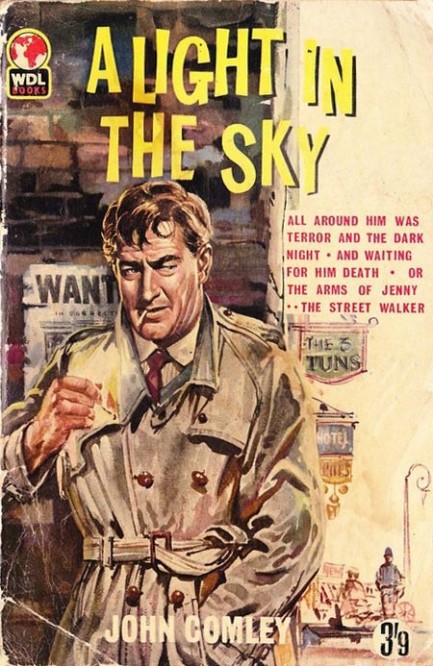

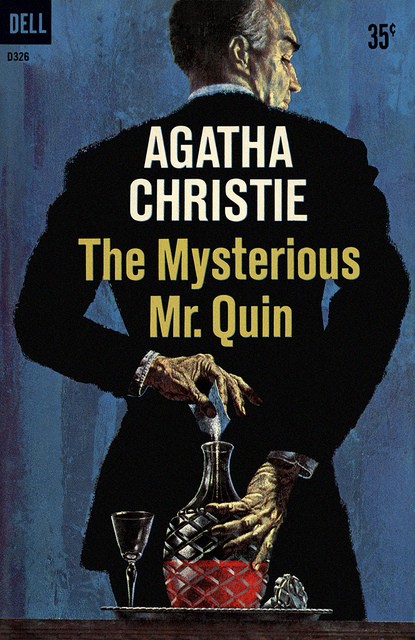

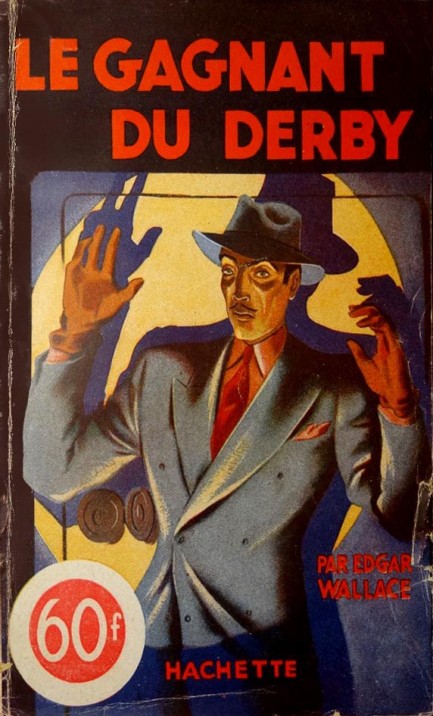

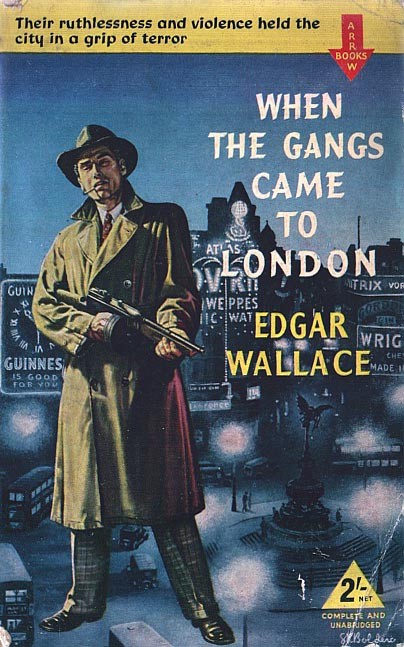

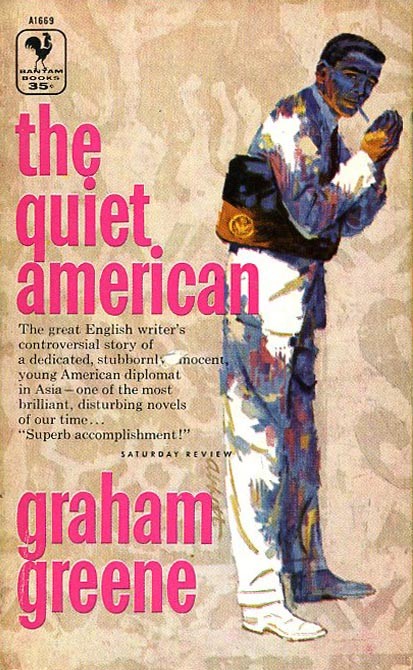

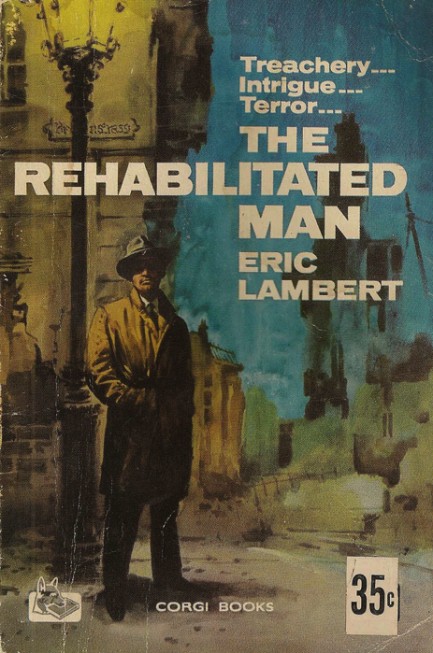

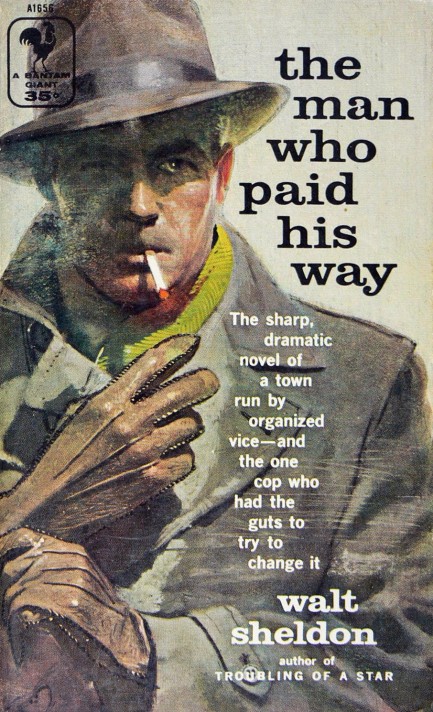

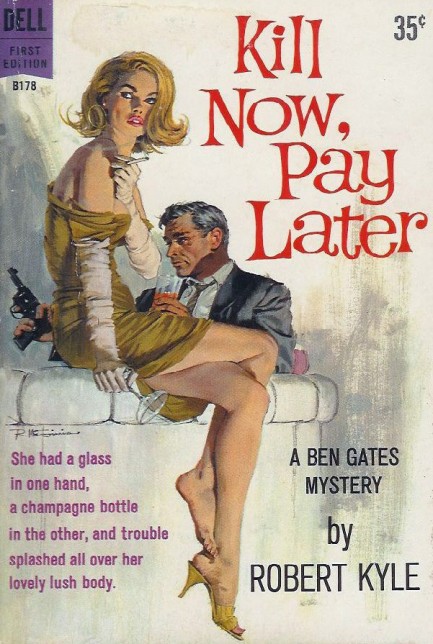

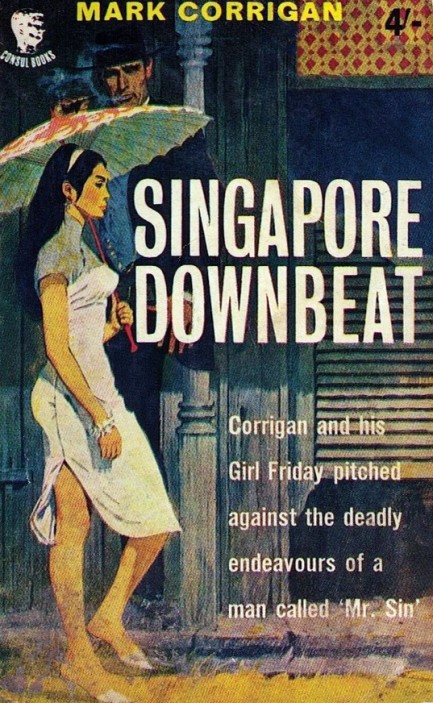

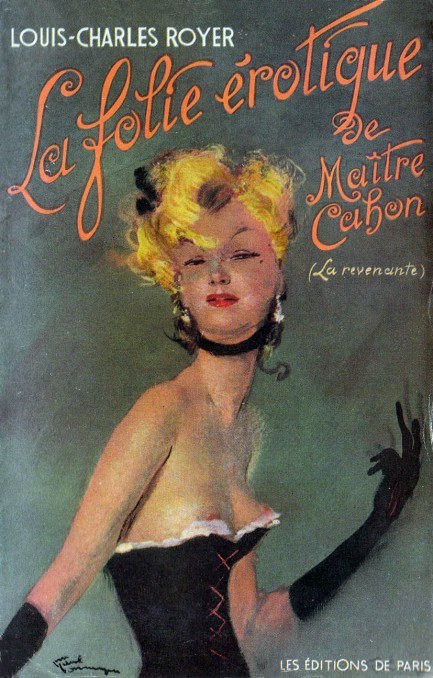

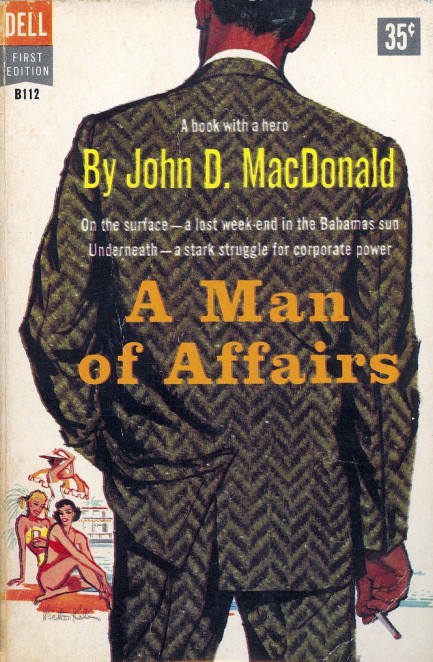

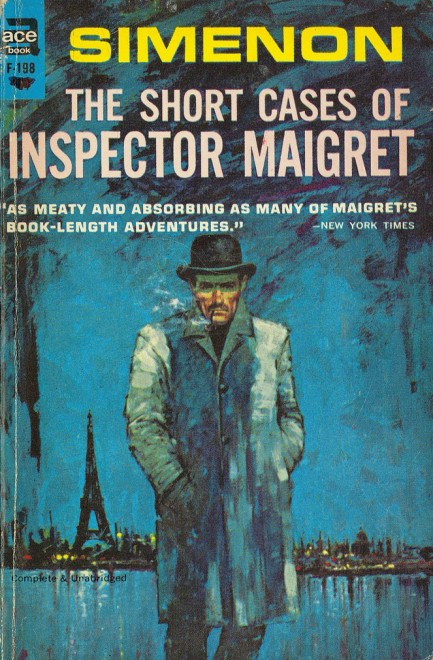

Never trust a man in expensive clothes.

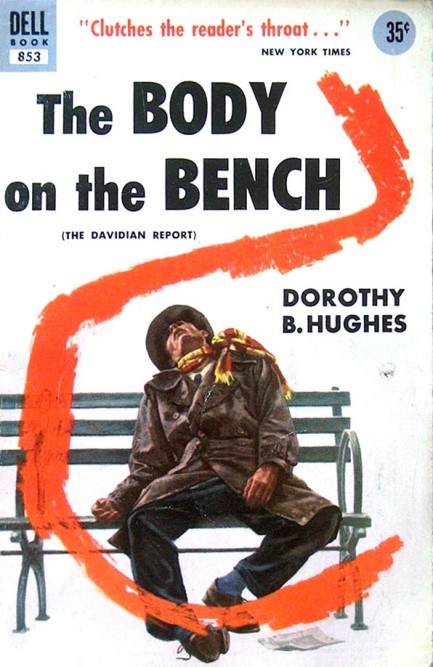

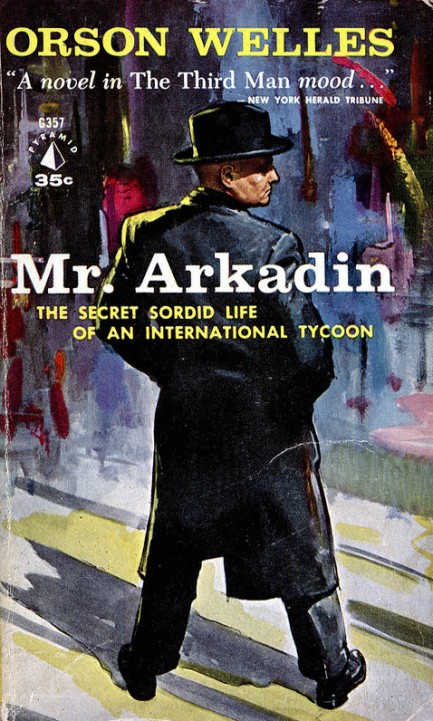

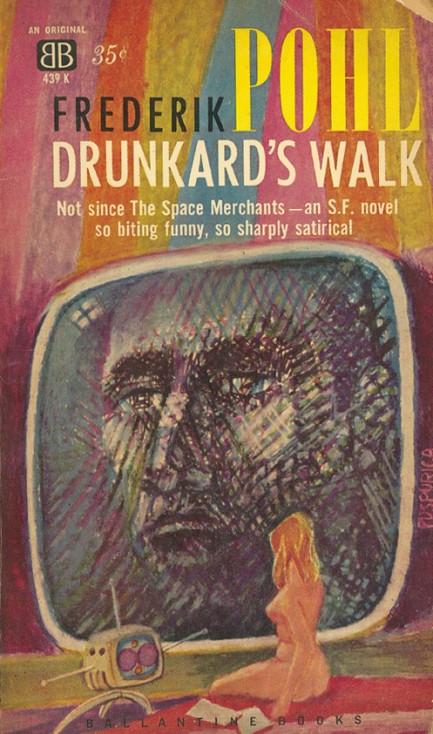

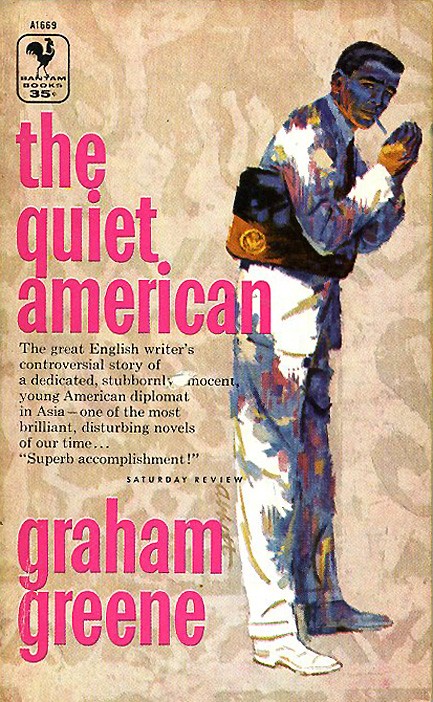

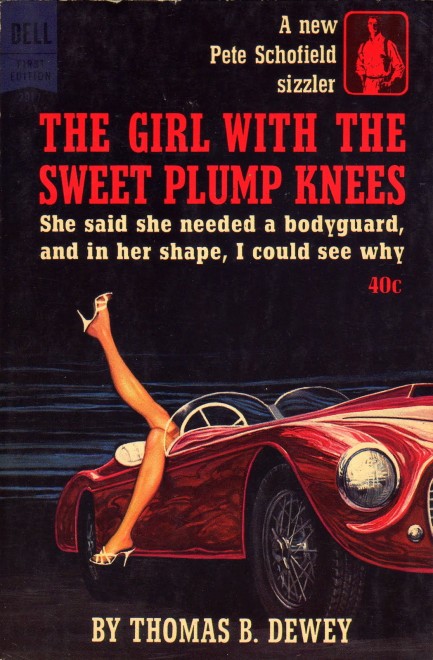

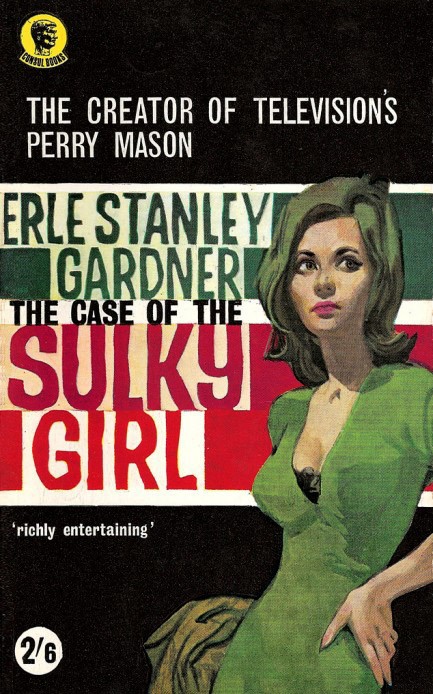

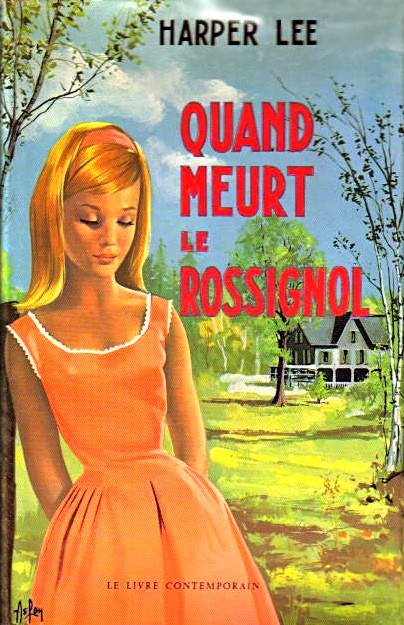

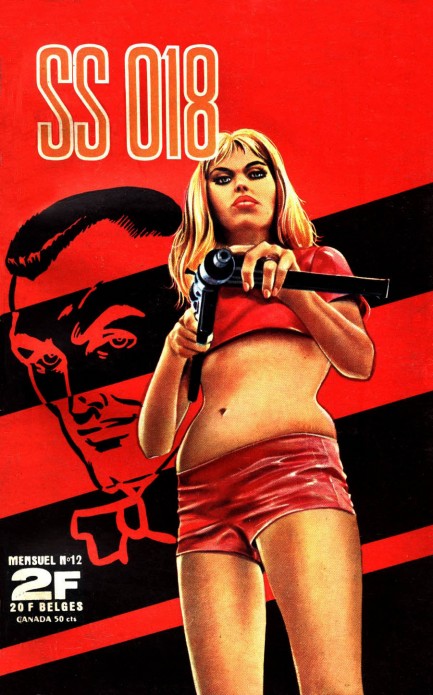

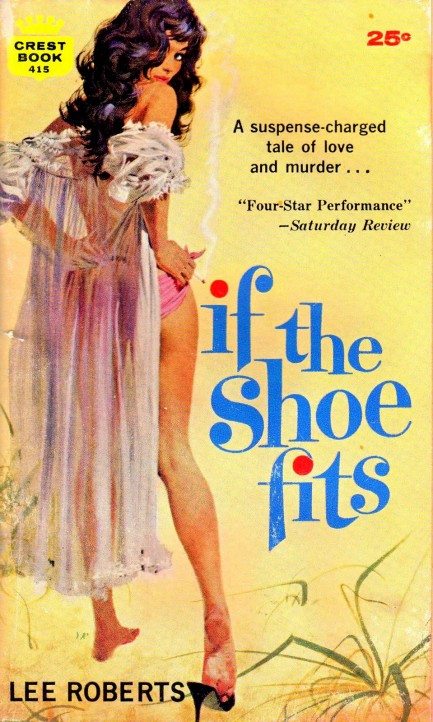

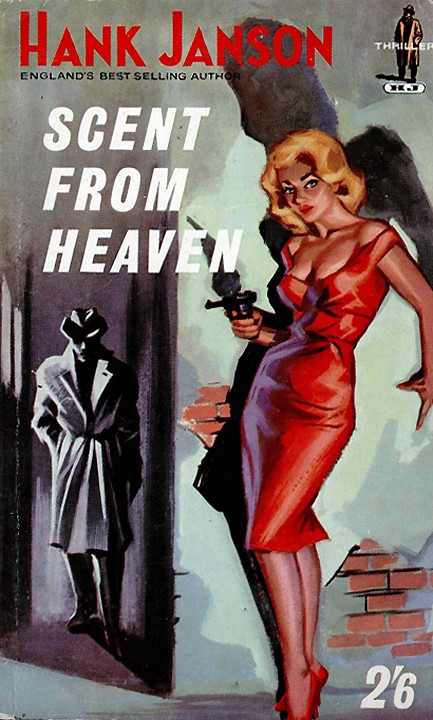

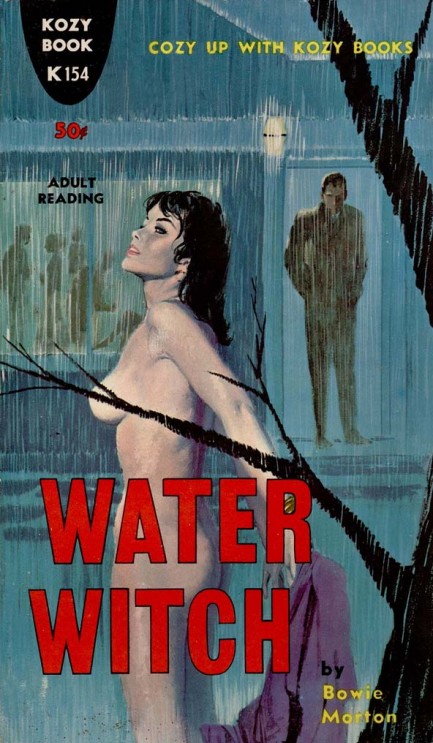

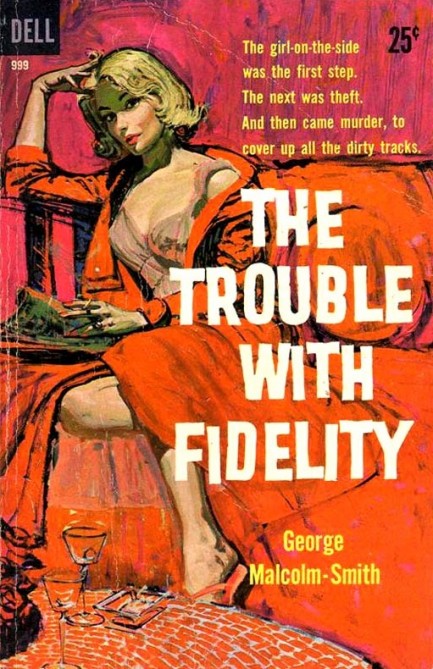

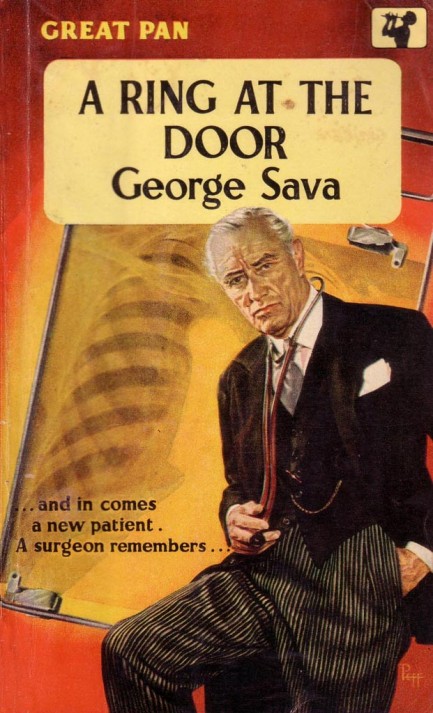

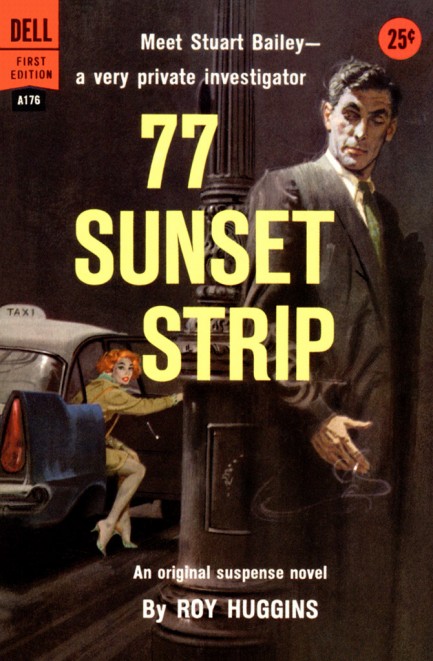

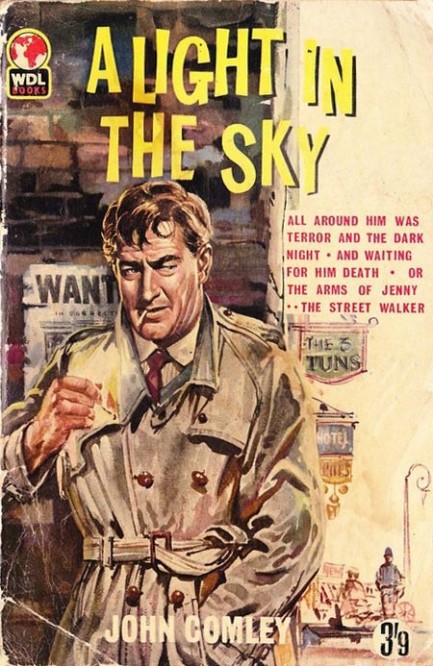

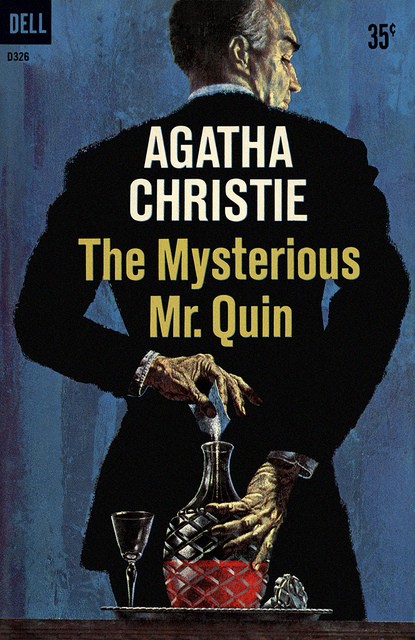

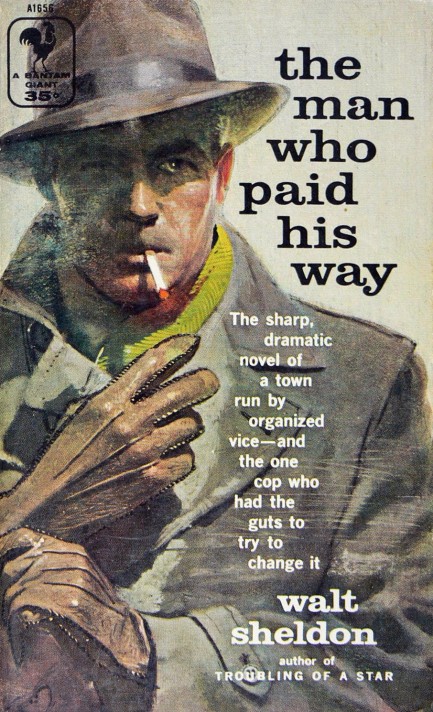

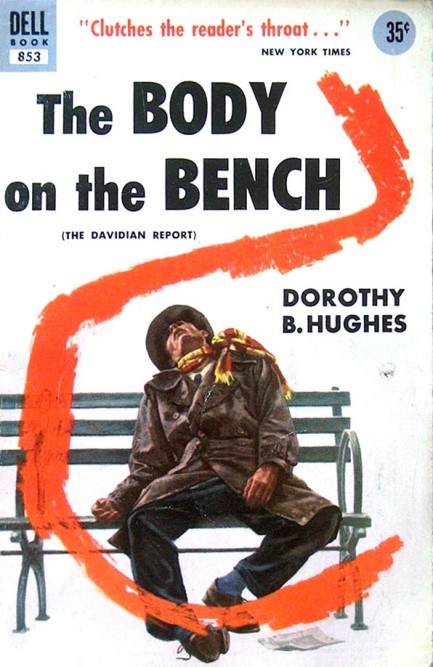

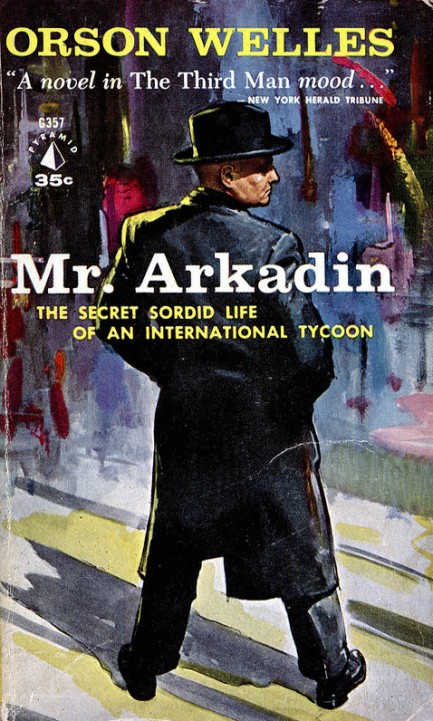

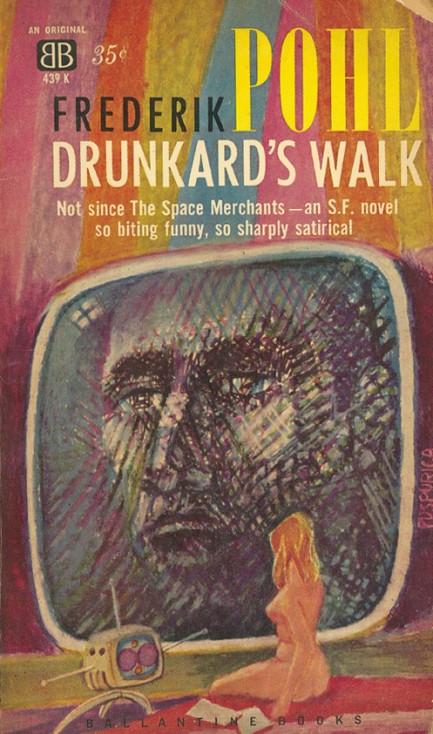

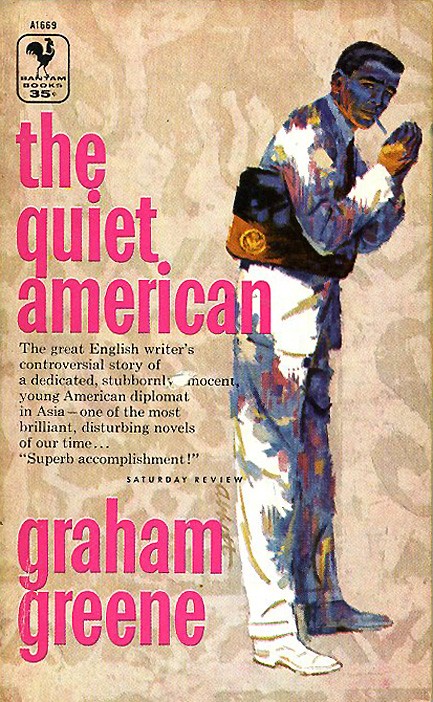

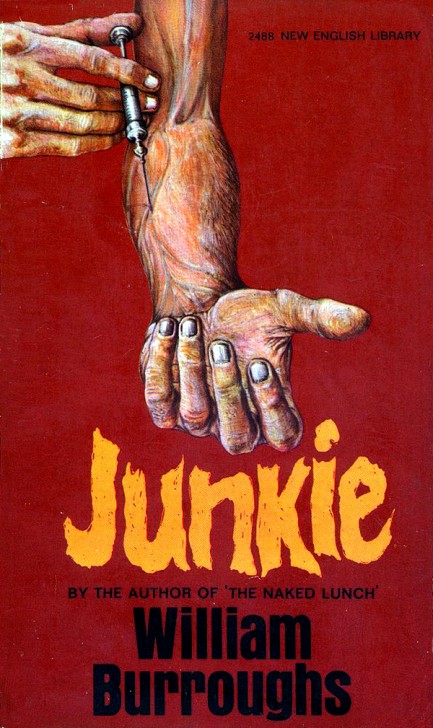

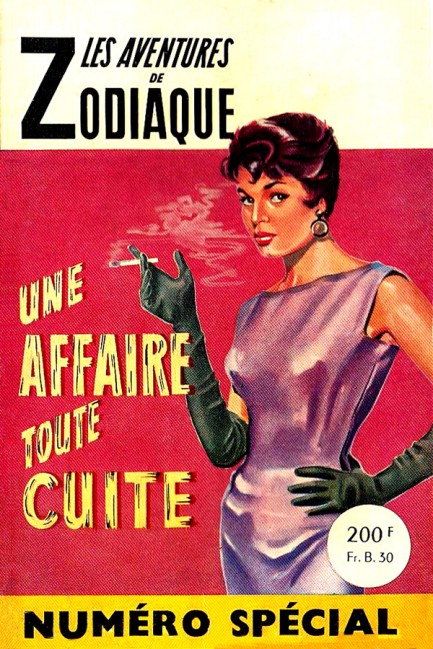

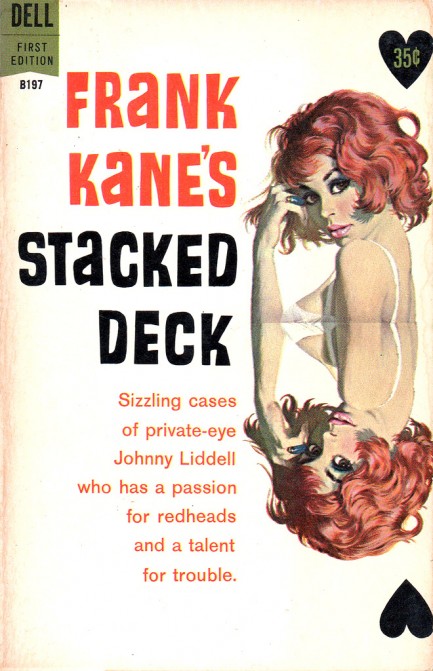

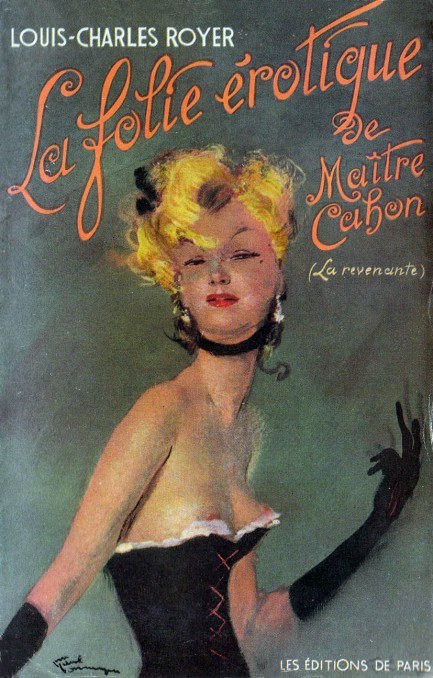

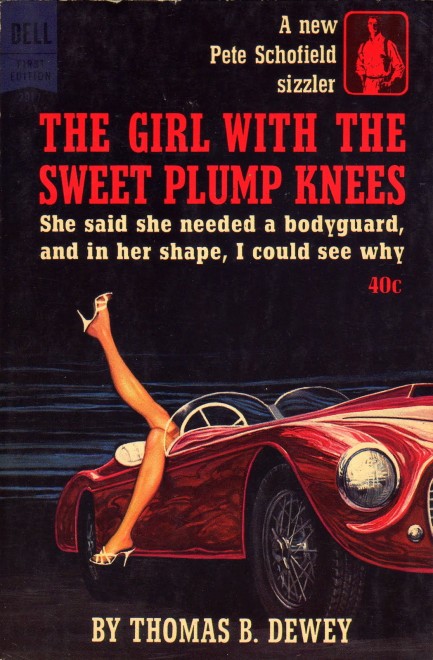

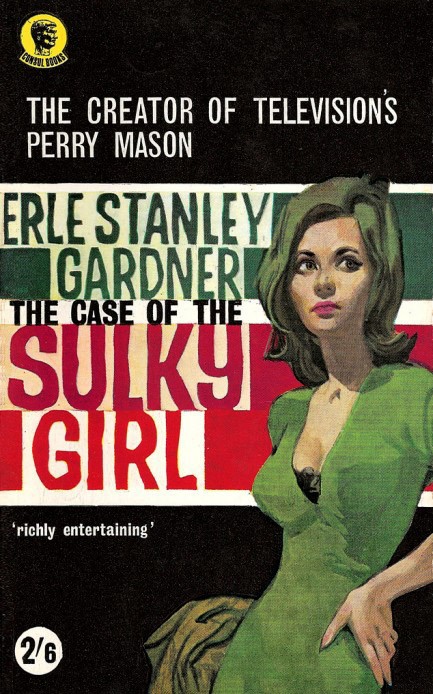

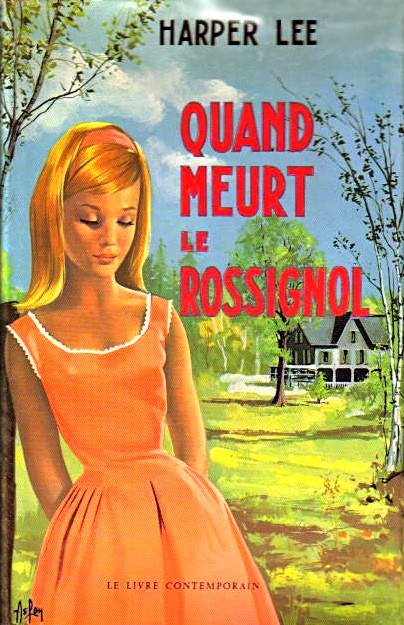

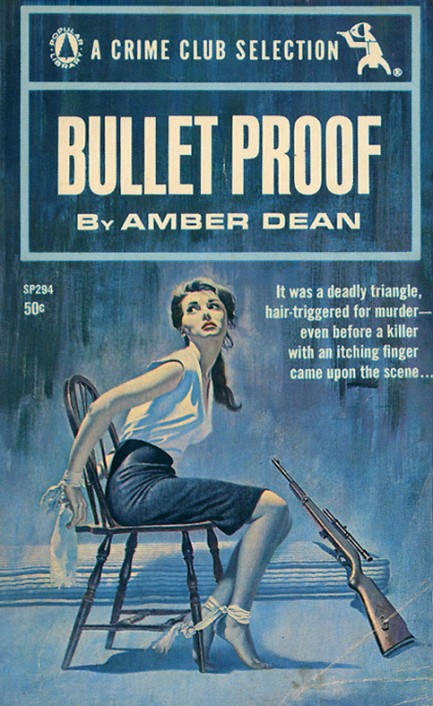

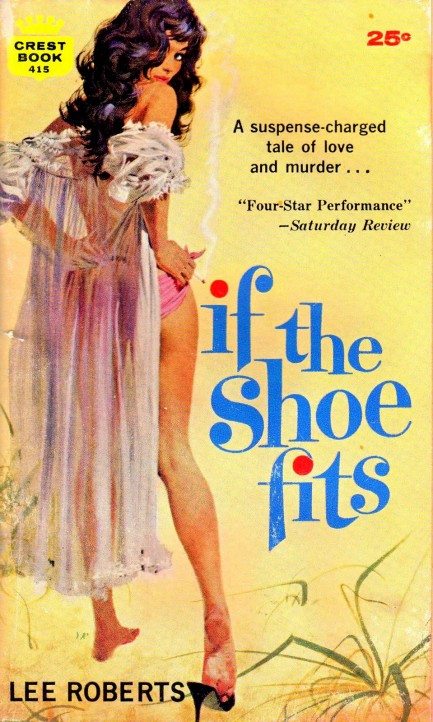

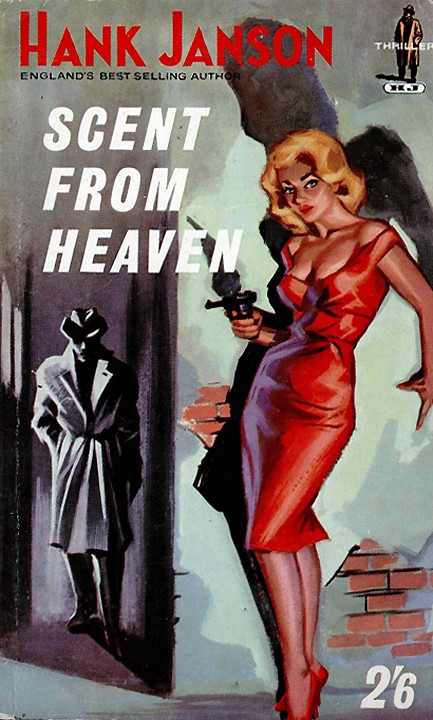

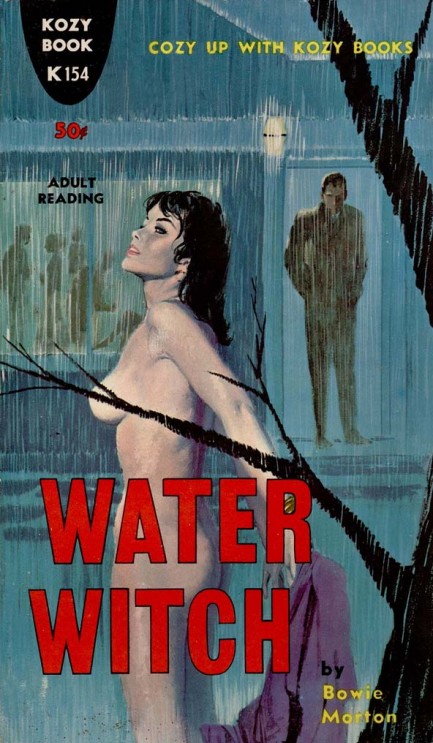

The Pulp Intl. girlfriends want more depictions of men on the site. Can we oblige them? Probably not. Vintage paperback art features women about ninety percent of the time, and they’re often scantily clothed. Men, on the occasions they appear, are not only typically dressed head to toe, but are often sartorially splendid. There are exceptions—beach-themed covers, bedroom depictions, gay fiction, and romances often feature stripped down dudes. We’ll assemble some collections of all those going forward, but today the best we can offer is an assortment of g’d up alpha males, with art by Victor Kalin, Robert McGinnis, and others. Enjoy.

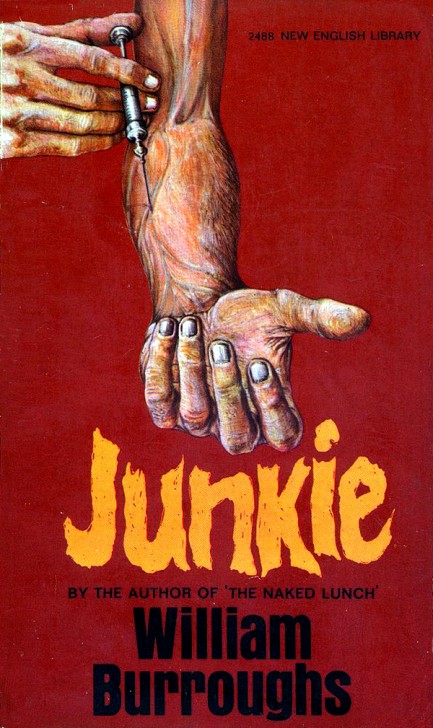

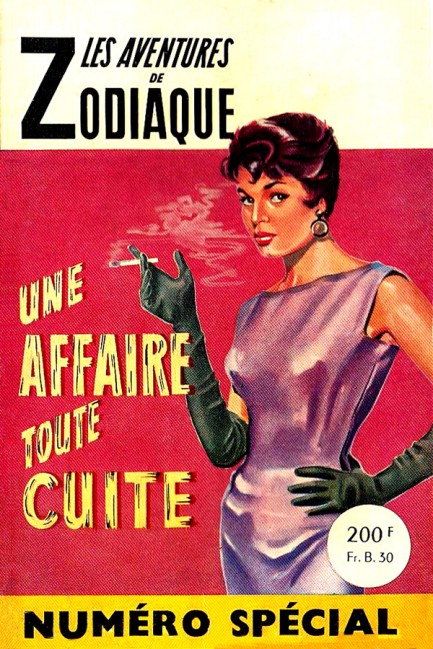

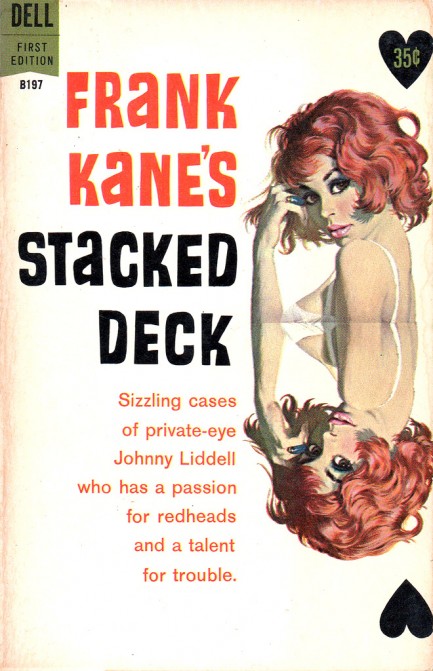

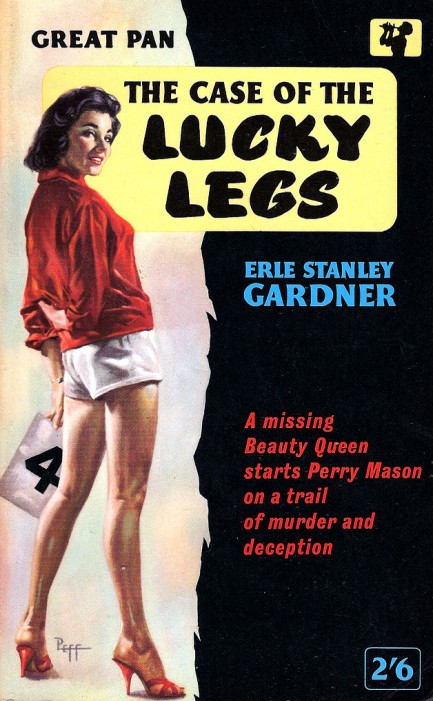

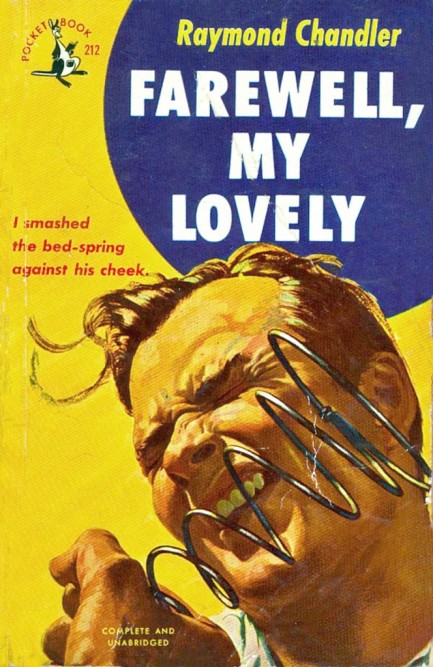

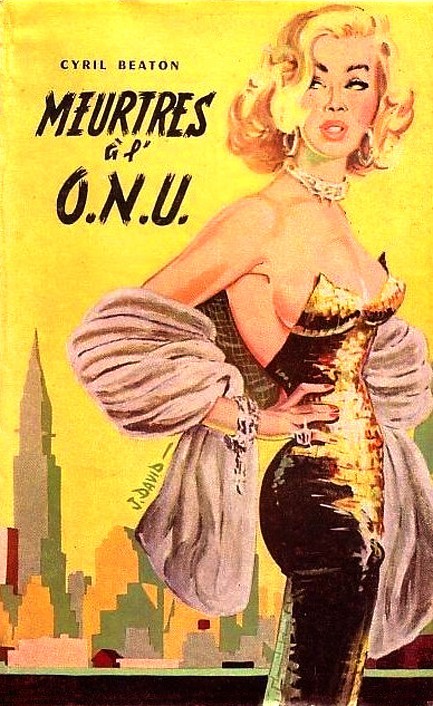

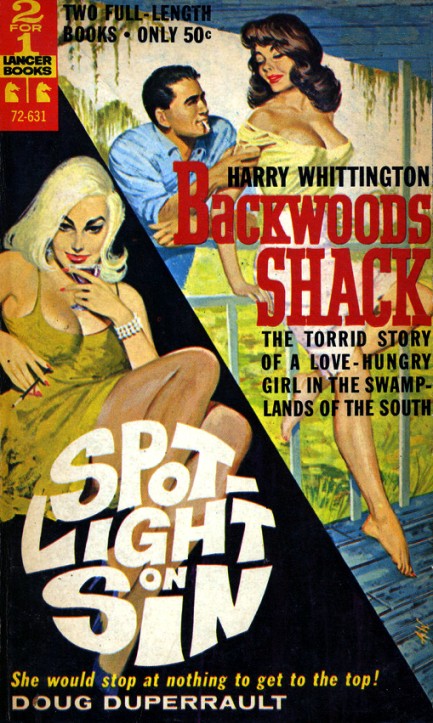

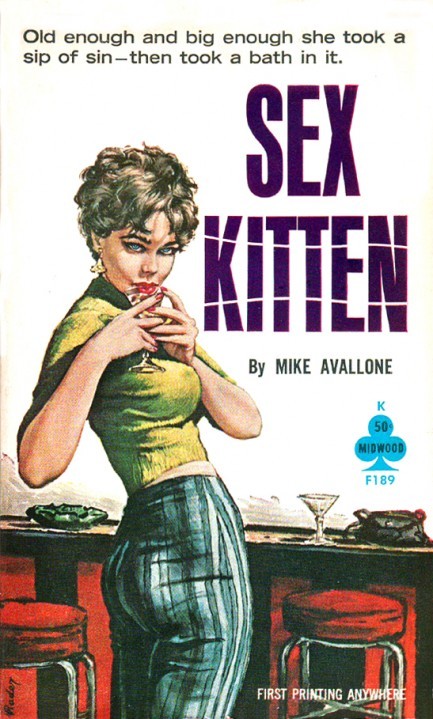

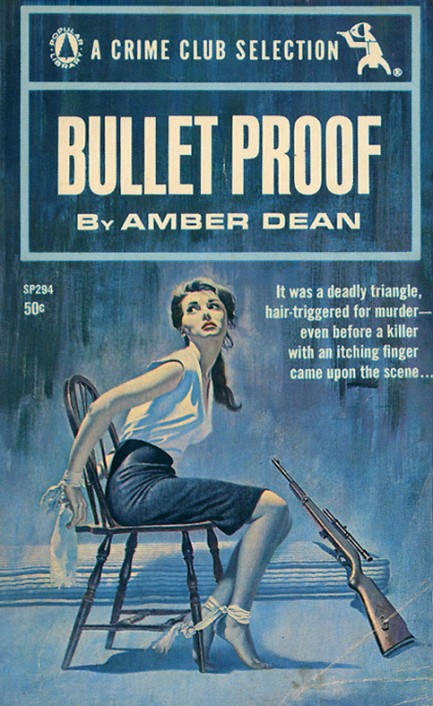

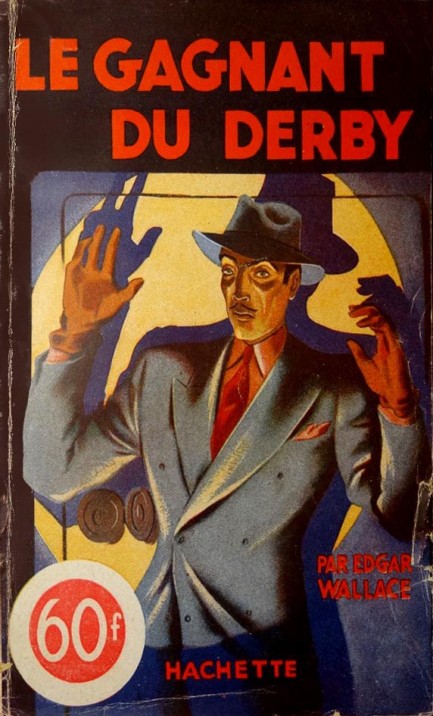

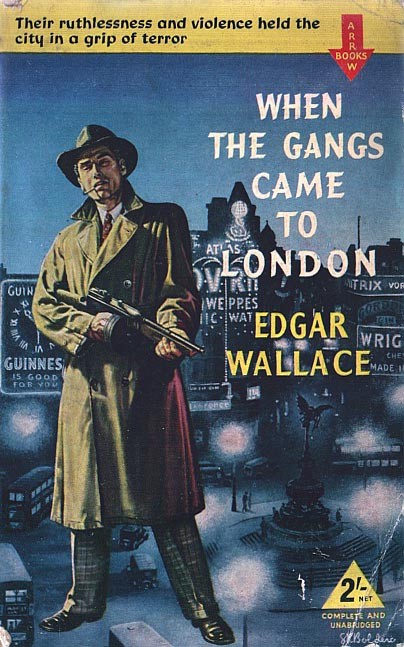

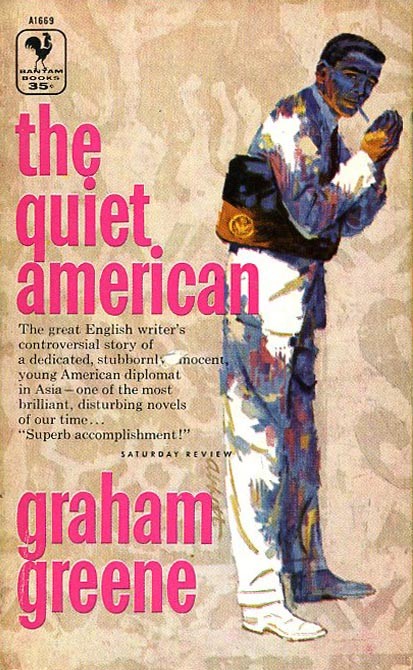

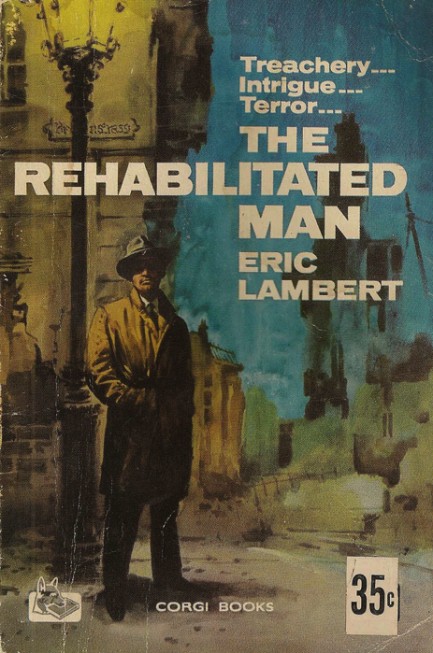

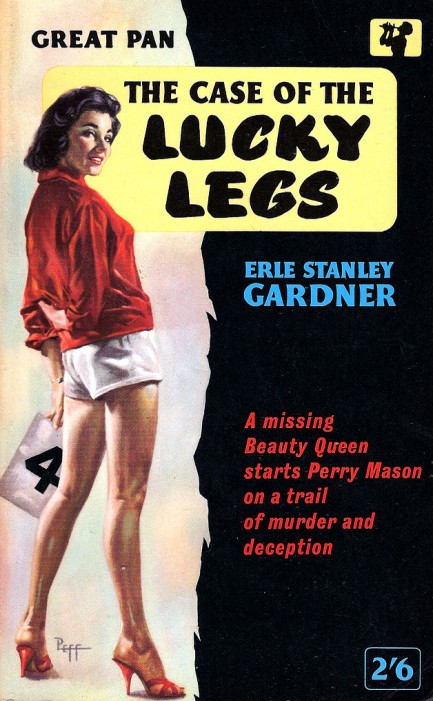

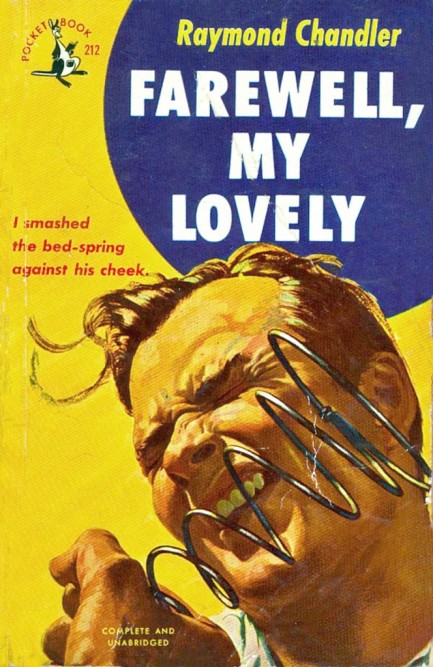

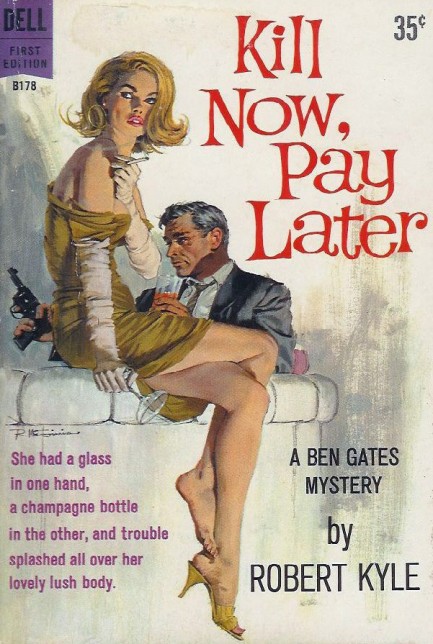

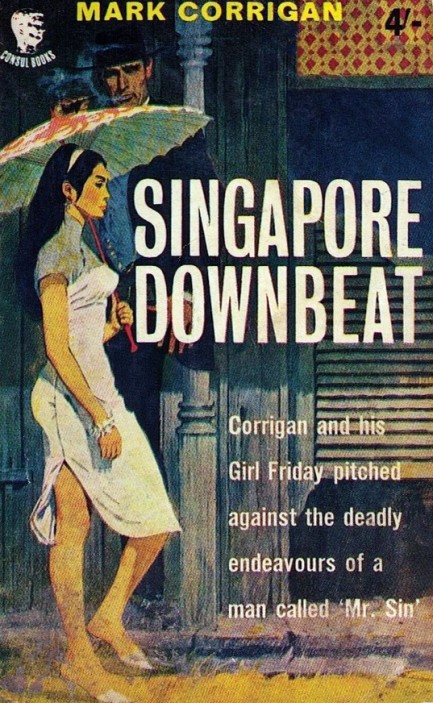

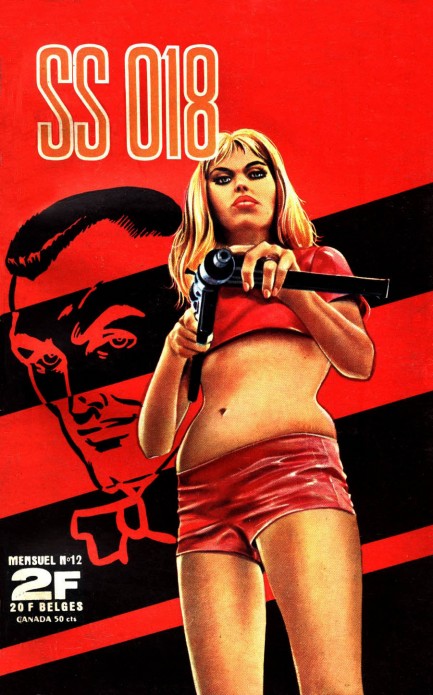

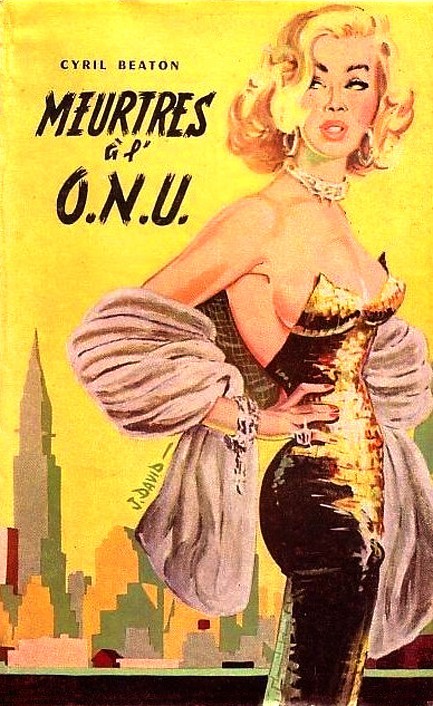

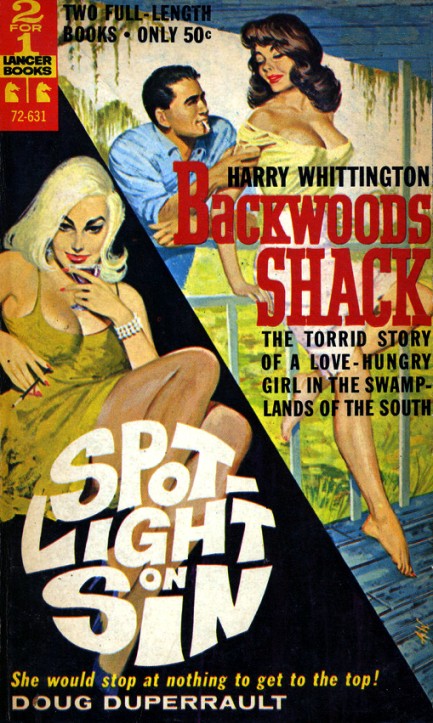

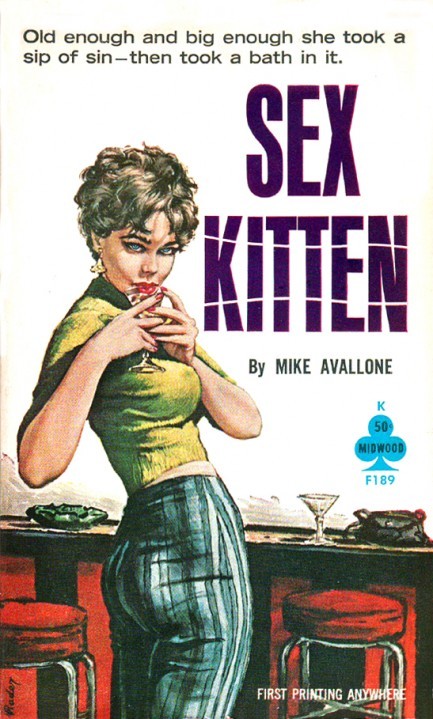

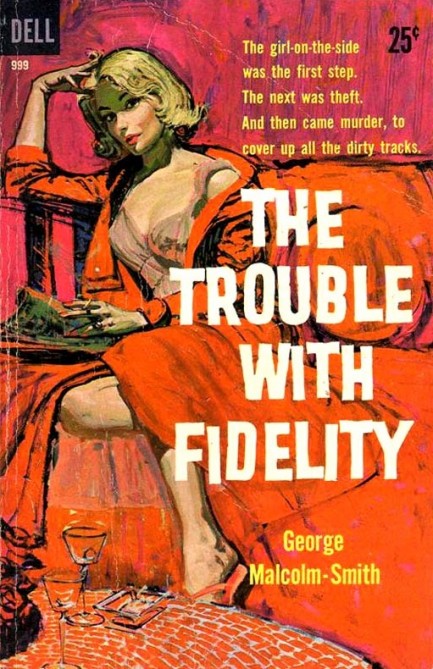

Does this look like one of the top sixty pulp book covers of all time to you?

No, it doesn’t look like that to us either. Don’t get us wrong. It isn’t bad. But top sixty? Ever? Yet we found it on a site that included it in its top sixty, along with a collection of other covers of which we can honestly say only three were excellent. There was not one Fixler or Aslan to be found. Nary a J. David, nor a Peff, nor even a hint of a Rader. Clearly, whoever put the feature together took sixty random images off Flickr (yet watermarked the art they borrowed) and called it a day. This highlights one of the main problems with the internet: it’s difficult to know which sites are primarily focused upon providing information, and which exist solely to generate traffic revenue. A site can do both (as we try to do here with our very minimal ad presence), but when some corporate pulp site that possesses endless resources somehow misidentifies the pulp era as lasting from the 1950s to 1970s, and asserts that the term “pulp” was popularized by the movie Pulp Fiction, it’s clear that information has not only taken a back seat to traffic revenue—it’s being dragged 100 feet behind the car on a rope.

We would never presume to do something as subjective as select the best covers of all time, because who the hell are we? But we have, we hope, earned some credibility over the last three years. So on this, our official third anniversary, we're going to do a pulp cover collection of our own. We don't claim these are the best—only that we like them very much. We’re posting twenty-four because we’re too lazy to do sixty, but we think all of them are winners. A few have already appeared on our site; most have not. So here we go. And thanks to the sites from which we borrowed some of these.

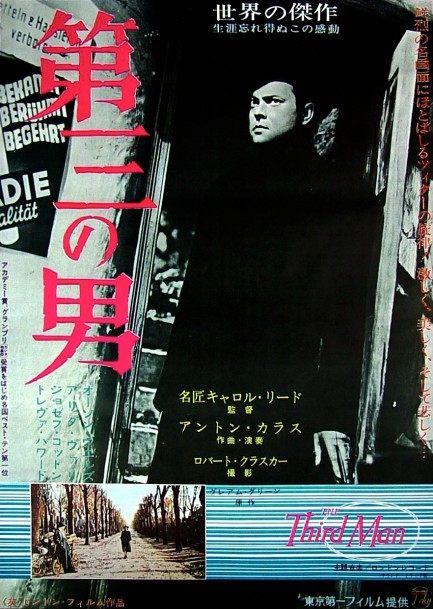

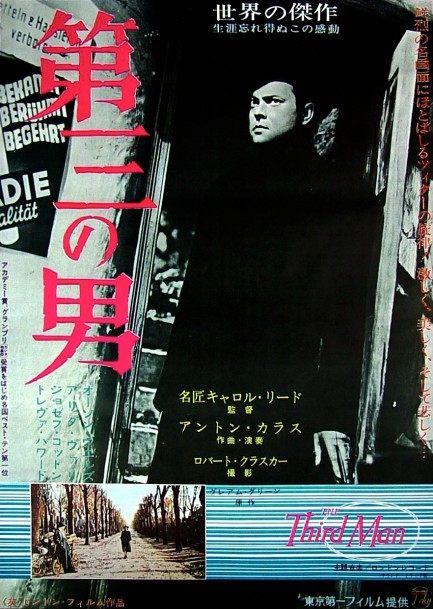

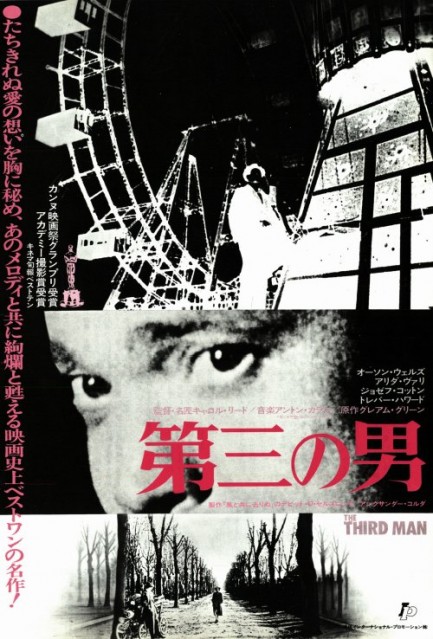

The Third Man is a stiff drink, with a twist of Lime.

The 1949 film noir The Third Man is a best-case-scenario of what can happen when great talents collaborate. Carol Reed directs, Orson Welles, Alida Valli and Joseph Cotten act from a screenplay penned by master storyteller Graham Greene, and the cinematographer is Robert Krasker. Krasker won an Academy Award for his work here, and when you see the velvety blacks and knifing shadows of his nighttime set-ups, as well as the famed scenes shot in the cavernous Vienna sewers and bombed out quadrants of the city center, you’ll understand why. The story involves a pulp writer named Holly Martins who arrives in a partitioned post-war Vienna only to find that his friend Harry Lime is dead, run down by a truck. When Martins learns that the police are disinterested in the circumstances of Lime’s demise, he decides to do what one of his pulp characters would do—take matters into his own hands. But nothing adds up. He learns that Lime died instantly, or survived long enough to utter a few last words. He finds that Lime was a racketeer, or possibly not. And he discovers that two men were present when Lime died—or possibly three. That third man seems to be the key to the mystery, but he proves to be damnably elusive. We can’t recommend this film highly enough. Above you see a pair of rare Japanese posters from The Third Man’s premiere in Tokyo today in 1952.

Havana when it sizzles. .jpg)

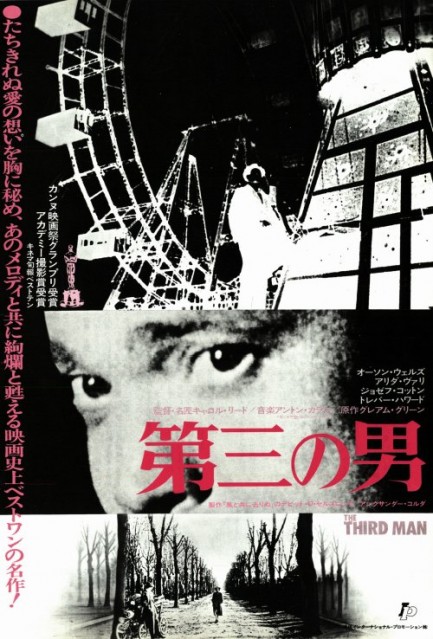

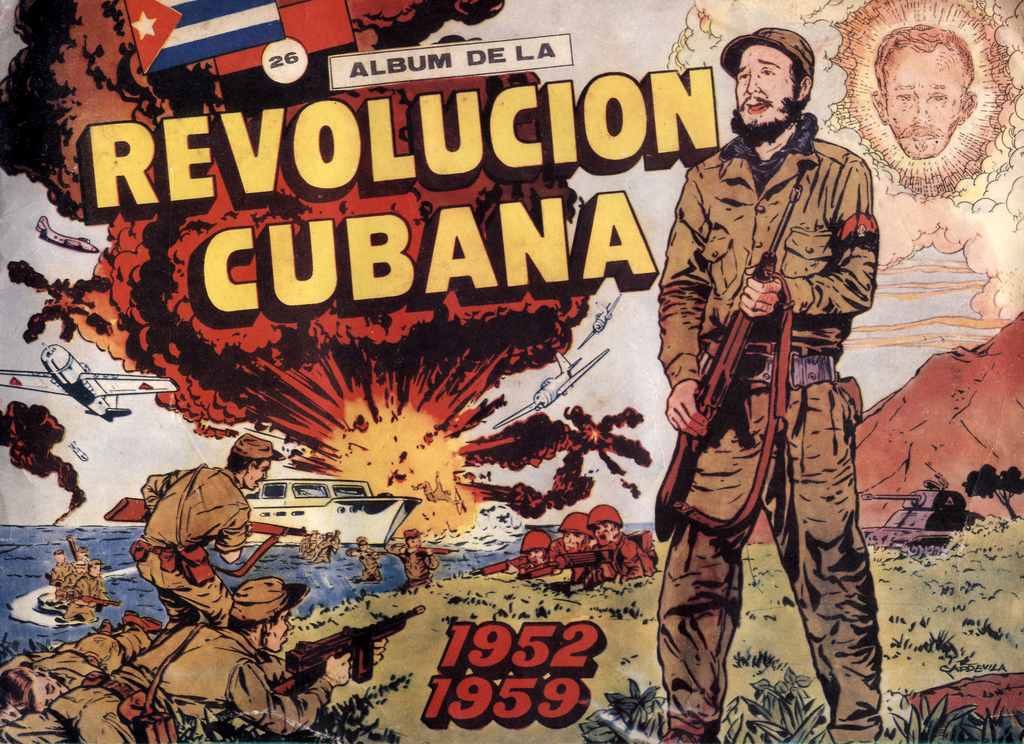

Fifty years ago on this day, U.S.-installed dictator Fulgencio Batista fled Cuba, acknowledging defeat by socialist forces aligned with Fidel Castro. At the time Cuba was controlled by U.S. business interests and organized crime figures, with 75% of its land in foreign hands, and the capital of Havana serving as an international vice playground. It was known as the Monte Carlo of the Caribbean, and establishments like the Tropicana, San Souci, and Shanghai Theatre were famous for casinos, prostitutes, and totally nude cabaret shows. The El Dorado had an all female orchestra. Mobster Meyer Lansky was royalty. Luminaries such as Frank Sinatra, Nat King Cole, and Edith Piaf were regular headliners. Havana was simply the place to be.

Less than an hour from Florida by air, New York businessmen who’d told their wives they were at a Miami conference could be enjoying a Cuban whore by lunchtime, and be back in Dade County in time for bed and a phone call from the missus. Alternatively, they could stay all night, or for days at a time, and lose themselves in daiquiris, dancing girls, and the lure of forbidden Barrio Colón. It was paradise—at least if you were a foreigner or one of the wealthy Cubans in partnership with them. For the poor Havana was pure hell. The billions in revenue earned by casinos and hotels trickled not down, but out—into foreign bank accounts. Malnutrition, illiteracy, and crime were rampant. When Castro ran Batista off the island the party cautiously continued, because his political intentions were not immediately clear. Everyone knew the old system would change; nobody knew exactly how much. But for a brief, post-revolutionary moment Cuba remained open to foreigners, and so the expatriate carnival went on—albeit under a cloud. poor Havana was pure hell. The billions in revenue earned by casinos and hotels trickled not down, but out—into foreign bank accounts. Malnutrition, illiteracy, and crime were rampant. When Castro ran Batista off the island the party cautiously continued, because his political intentions were not immediately clear. Everyone knew the old system would change; nobody knew exactly how much. But for a brief, post-revolutionary moment Cuba remained open to foreigners, and so the expatriate carnival went on—albeit under a cloud.

But the lines had already been drawn in the greatest ideological battle of modern times. U.S. president Dwight D. Eisenhower was using the CIA to train Cuban exiles for an invasion to oust the socialists, and Castro was planning to nationalize a corrupt capitalist economy that had excluded those who were too poor, too black, or too lacking in influence to get a seat at the big table. When Castro made nationalization official, the U.S. struck with an embargo, and followed up five months later with the failed Bay of Pigs invasion. Since then the ideological battle lines have occasionally shifted, but Cuba remains the prize jewel of the war. Bay of Pigs invasion. Since then the ideological battle lines have occasionally shifted, but Cuba remains the prize jewel of the war.

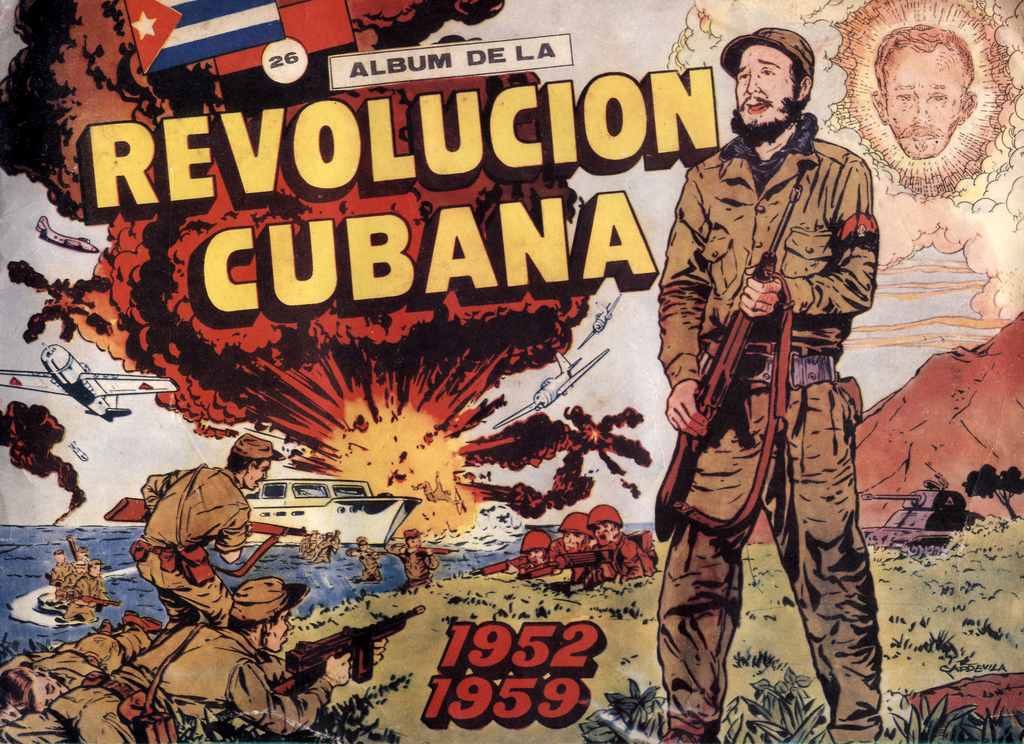

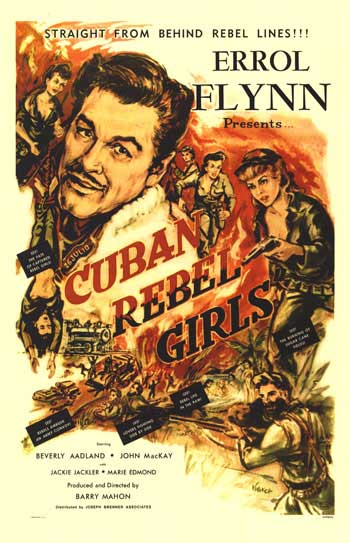

As historical events go, the Cuban Revolution, as well as its prelude and aftermath, have been invaluable to genre fiction, providing rich material for authors such as Graham Greene, James Ellroy and a literary who’s-who of others. It has been the subject of countless revisionist potboilers. Stephen Hunter’s Havana is perhaps the best of these novels, at least by an American writer. In that one Fidel’s fate is in the hands of a goodhearted redneck from Arkansas. Sent by the CIA, the heroic marksman is more than a match for the hapless Cubans, but does he really want to kill Castro? Daniel Chevarría went Hunter one better and wrote several novels set in Cuba, including Tango for a Torturer and the award winner Adios Muchachos. Movies ranging from Errol Flynn’s piece-of-fluff Cuban Rebel Girls, to Wim Wenders’ inspiring Buena Vista Social Club, to Benicio del Toro’s heavyweight Ché have also used the island as a backdrop. Doubtless Cuba will provide material for as long as authors write and directors yell action, as its history continues to inspire, and its future continues to be in flux.

|

|

The headlines that mattered yesteryear.

2003—Hope Dies

Film legend Bob Hope dies of pneumonia two months after celebrating his 100th birthday. 1945—Churchill Given the Sack

In spite of admiring Winston Churchill as a great wartime leader, Britons elect

Clement Attlee the nation's new prime minister in a sweeping victory for the Labour Party over the Conservatives. 1952—Evita Peron Dies

Eva Duarte de Peron, aka Evita, wife of the president of the Argentine Republic, dies from cancer at age 33. Evita had brought the working classes into a position of political power never witnessed before, but was hated by the nation's powerful military class. She is lain to rest in Milan, Italy in a secret grave under a nun's name, but is eventually returned to Argentina for reburial beside her husband in 1974. 1943—Mussolini Calls It Quits

Italian dictator Benito Mussolini steps down as head of the armed forces and the government. It soon becomes clear that Il Duce did not relinquish power voluntarily, but was forced to resign after former Fascist colleagues turned against him. He is later installed by Germany as leader of the Italian Social Republic in the north of the country, but is killed by partisans in 1945.

|

|

|

It's easy. We have an uploader that makes it a snap. Use it to submit your art, text, header, and subhead. Your post can be funny, serious, or anything in between, as long as it's vintage pulp. You'll get a byline and experience the fleeting pride of free authorship. We'll edit your post for typos, but the rest is up to you. Click here to give us your best shot.

|

|

Here, have your cake. And eat it too. Heh.

Here, have your cake. And eat it too. Heh. I prefer blood sausage for train trips, but I guess it's better for you I'm not shoving one of those in your face, eh?

I prefer blood sausage for train trips, but I guess it's better for you I'm not shoving one of those in your face, eh?

Wow, you sort of... crush the shit out of your cake before eating it.

Wow, you sort of... crush the shit out of your cake before eating it. Have I been eating cake wrong the whole time I've been in England?

Have I been eating cake wrong the whole time I've been in England?

.jpg)

poor Havana was pure hell. The billions in revenue earned by casinos and hotels trickled not down, but out—into foreign bank accounts. Malnutrition, illiteracy, and crime were rampant. When Castro ran Batista off the island the party cautiously continued, because his political intentions were not immediately clear. Everyone knew the old system would change; nobody knew exactly how much. But for a brief, post-revolutionary moment Cuba remained open to foreigners, and so the expatriate carnival went on—albeit under a cloud.

poor Havana was pure hell. The billions in revenue earned by casinos and hotels trickled not down, but out—into foreign bank accounts. Malnutrition, illiteracy, and crime were rampant. When Castro ran Batista off the island the party cautiously continued, because his political intentions were not immediately clear. Everyone knew the old system would change; nobody knew exactly how much. But for a brief, post-revolutionary moment Cuba remained open to foreigners, and so the expatriate carnival went on—albeit under a cloud. Bay of Pigs invasion. Since then the ideological battle lines have occasionally shifted, but Cuba remains the prize jewel of the war.

Bay of Pigs invasion. Since then the ideological battle lines have occasionally shifted, but Cuba remains the prize jewel of the war.