| Femmes Fatales | Mar 16 2024 |

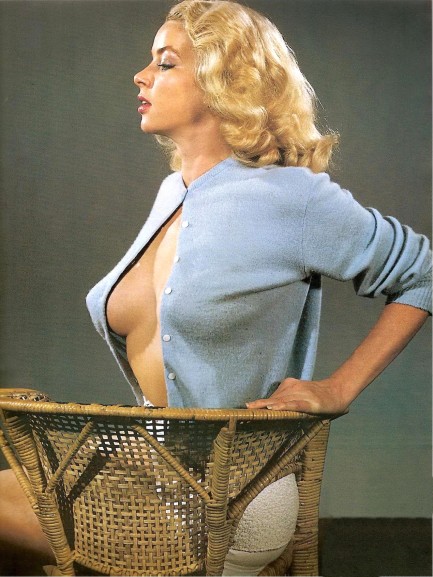

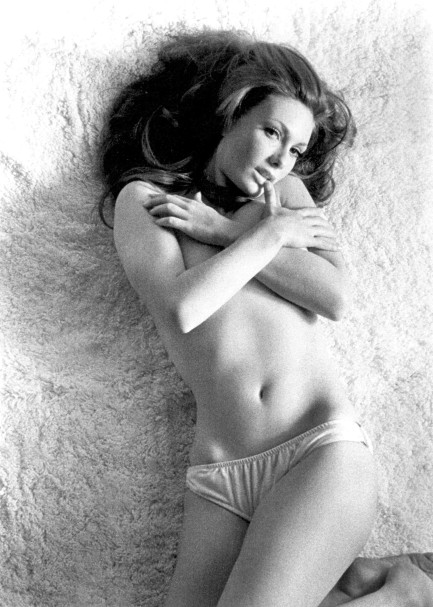

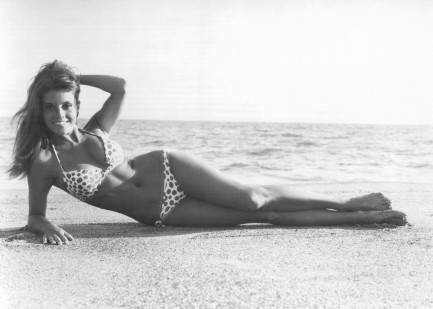

The exact opposite of buttoned up tight.

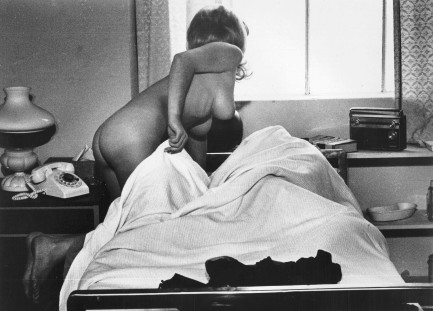

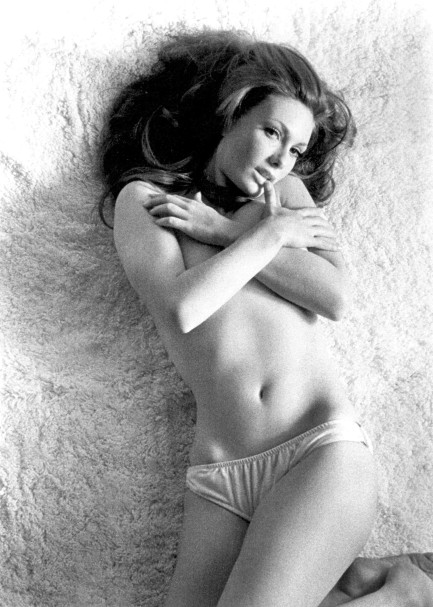

Eve Meyer, who was Eve Turner before marrying filmmaker Russ Meyer, is seen here in a photo made when she was a Playboy centerfold in 1955. A black and white version of the photo was included in that layout. After a few years modeling, Meyer appeared in several films, then produced fifteen movies, including Cherry, Harry & Raquel, Motorpsycho, and Beyond the Valley of the Dolls, all of which are schlock classics. We think this shot of her is classic too.

| Vintage Pulp | Oct 2 2023 |

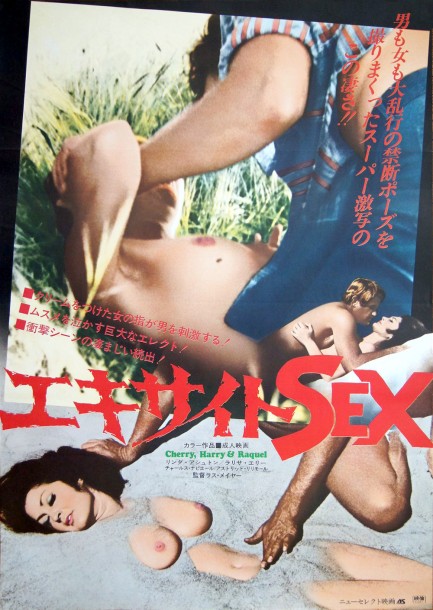

Russ Meyer and Co. do it in the desert.

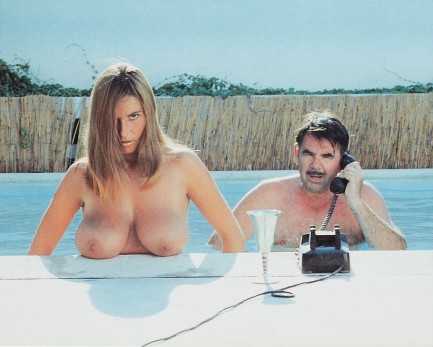

Above is a Japanese poster made for Cherry, Harry & Raquel, on which the local distributors splash that magical English word “Sex.” Twice we've discussed this practice and shared examples, here and here. The movie is one of numerous exploitation efforts from Russ Meyer, who graced American grindhouse cinemas with such dubious classics as Wild Gals of the Naked West, Motorpsycho!, Mondo Topless, Beyond the Valley of the Dolls, and Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill!

Cherry, Harry & Raquel deals with a bordertown sheriff and his sidekick who smuggle marijuana, and are instructed by their drug boss to kill a former partner who's gone into business on his own. The hunt-and-kill operation goes wrong, as the prey quickly becomes the predator. In Meyer's hands the film is something of a desertified hallucinogenic short, intercut with random scenes of nudity and seduction to stretch it to feature length. The sexual content is mostly played for laughs, and none of it is erotic. At least as far as we were concerned.

It was the poster and Meyer's name that drew us, and we were also a bit curious to check out b-movie legend Charles Napier in one of his earliest roles, but none of what we saw impressed us. When Meyer was on his game his movies could be entertaining. Faster Pussycat and Valley of the Dolls are both worth a watch just for their self-conscious silliness. But unless you're a Meyer completist, we recommend skipping Cherry, Harry & Raquel. It opened in the U.S. in 1969, and eventually reached Japan today in 1976.

| Vintage Pulp | Feb 18 2023 |

Some people just can't handle any excitement.

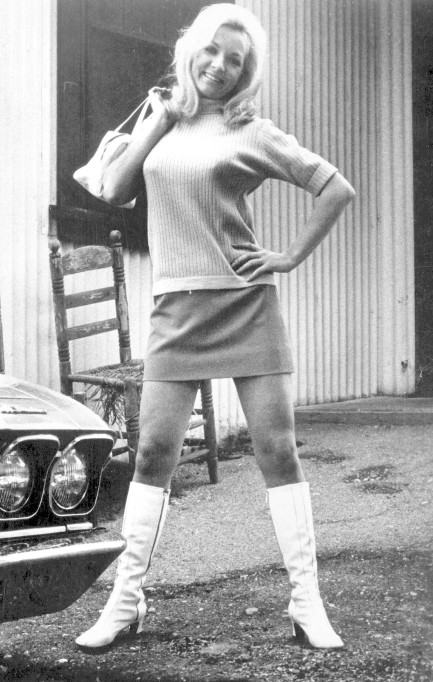

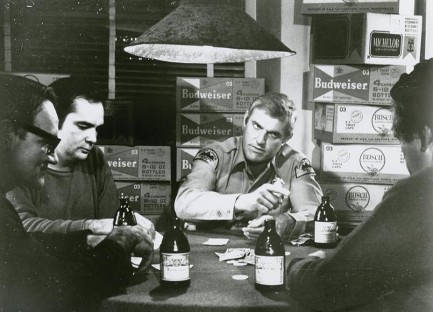

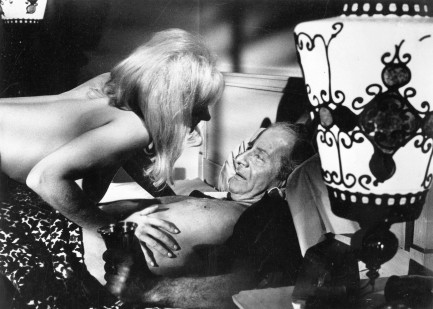

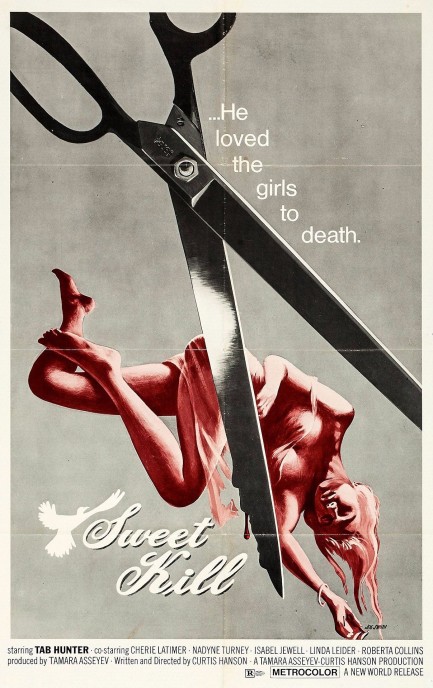

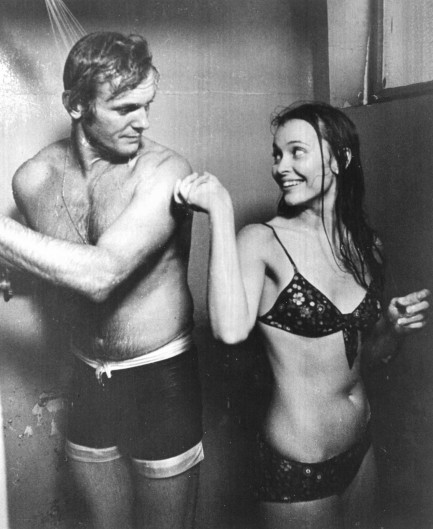

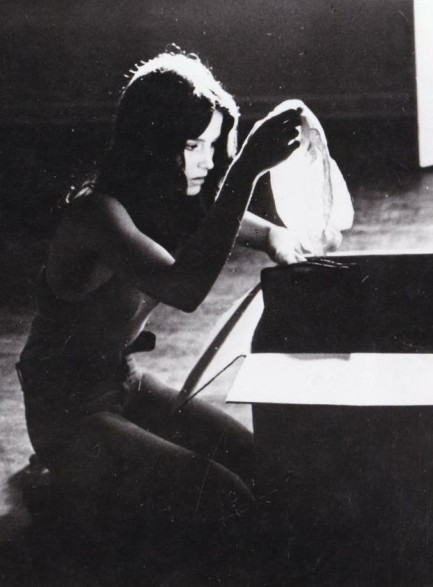

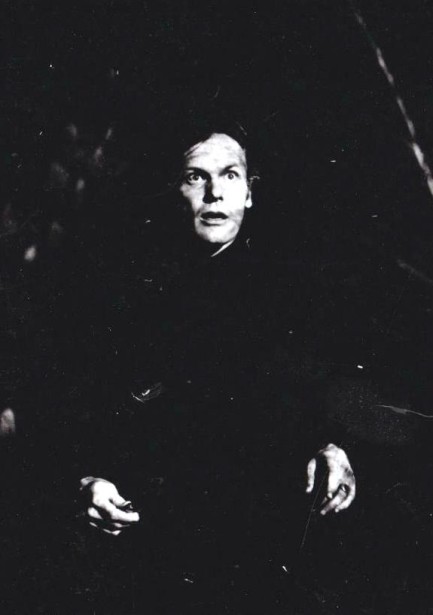

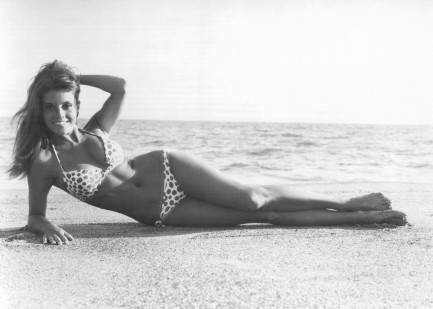

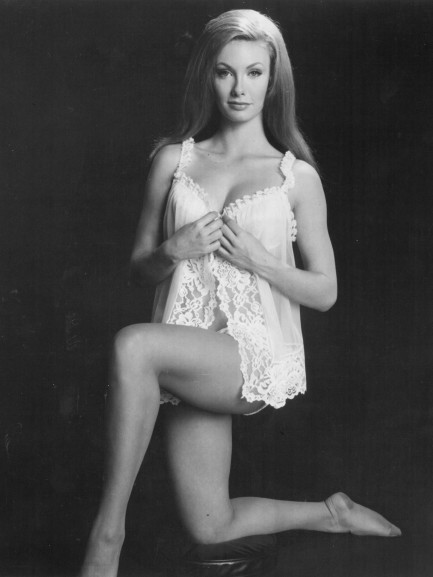

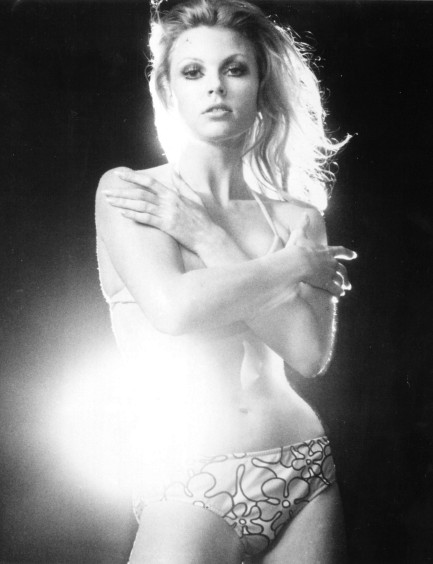

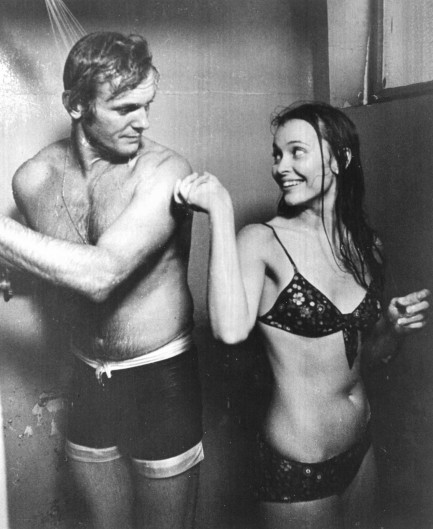

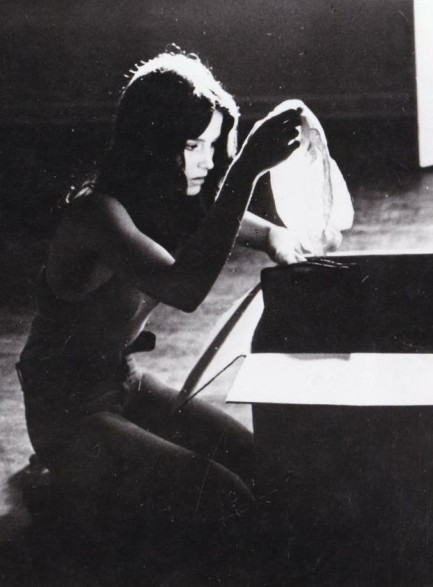

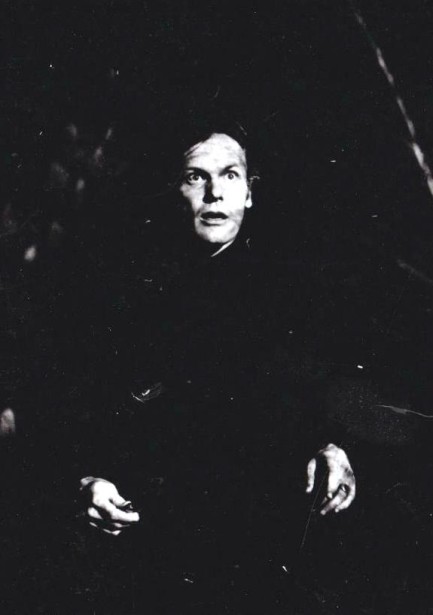

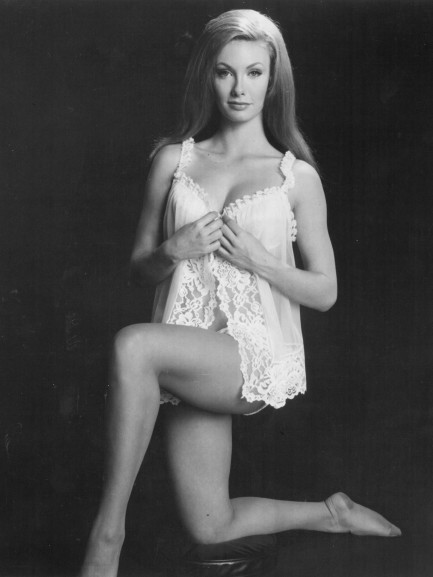

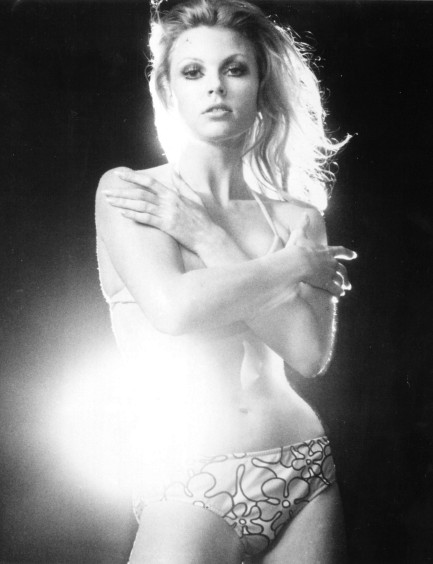

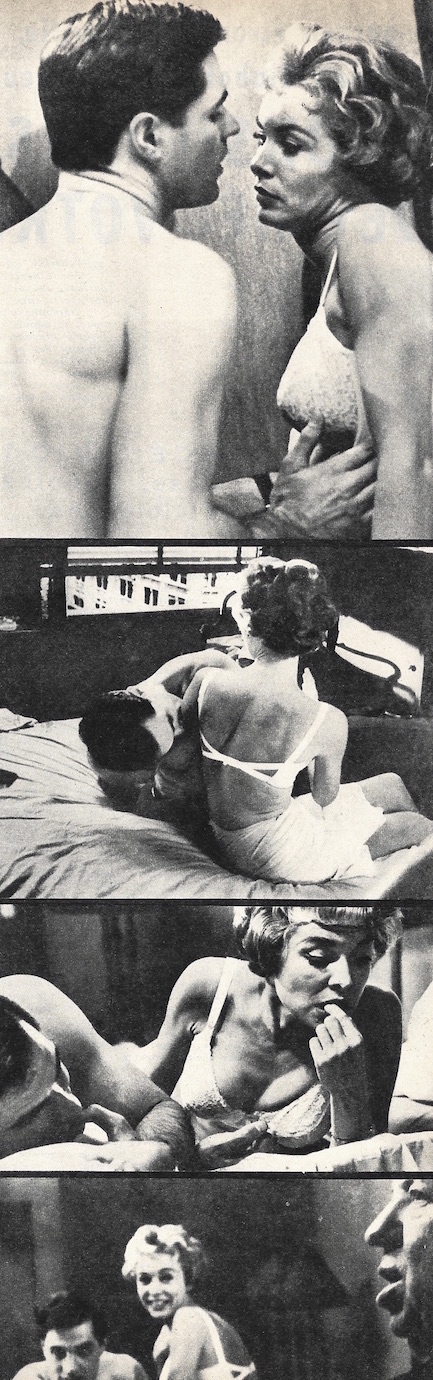

It's hard to believe that Curtis Hanson—the man who directed The River Wild, the acclaimed L.A. Confidential, and the underrated Wonder Boys, got his start with Sweet Kill, which he directed and wrote, but it's true. Everyone has to start somewhere. Even Francis Ford Coppola started in nudie flicks. Sweet Kill stars Tab Hunter, who plays a sort of beach hunk version of Norman Bates who stabs women when he's sexually aroused—hence the movie's alternate title, The Arousers. Those arousers, who you'll see below in a series of production photos made for the film, include Roberta Collins. Cherie Latimer, Brandy Herred, and others.

Sweet Kill is an interesting mood piece but we can't call the movie a success on the whole because it isn't scary—an aspiration for slasher flicks (its main inspiration Psycho is scary, after all). The main problem here is the acting, that bugaboo of ambitious young directors the world over. Collins is okay, but Hunter is out of his depth, and the other participants clearly didn't have the time and talent to hone their performances. In the end what you get is a lot of standing around, a fair amount of nudity, and minor tension derived from whether Hunter can somehow curb his murderous urges. Spoiler alert: he can't. Sweet Kill premiered in the U.S. today in 1972.

| Hollywoodland | Aug 29 2022 |

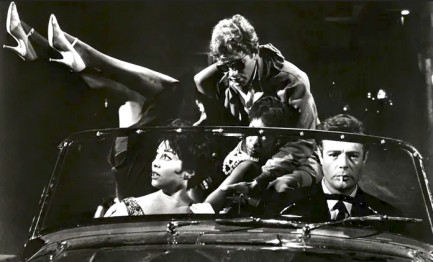

They're not really going anywhere but they look mighty good doing it.

What's a period drama without a fake driving scene? Nearly all such sequences were shot in movie studios using two techniques—rear projection, which was standard for daytime driving, and both rear projection and lighting effects for simulating night driving. Many movie studios made production images of those scenes. For example, above you see Jane Greer and Lizabeth Scott, neither looking happy, going for a fake spin around Los Angeles in 1951's The Company She Keeps. We decided to make a collection of similar shots, so below we have more than twenty other examples (plus a couple of high quality screen grabs) with top stars such as Humphrey Bogart, Ingrid Bergman, Barbara Stanwyck, Robert Mitchum, and Raquel Welch. We've only scratched the surface of this theme, which means you can probably expect a second collection somewhere down the road. Incidentally, if you want to see Bogart at his coolest behind the wheel look here, and just because it's such a wonderful shot, look here for Elke Sommer as a passenger. Enjoy today's rides.

Humphrey Bogart tries to fake drive with Ida Lupino in his ear in 1941's High Sierra.

Humphrey Bogart tries to fake drive with Ida Lupino in his ear in 1941's High Sierra. Dorothy Malone, Rock Hudson, and a rear projection of Long Beach, in 1956's Written on the Wind.

Dorothy Malone, Rock Hudson, and a rear projection of Long Beach, in 1956's Written on the Wind. Ann-Margret and John Forsythe in Kitten with a Whip. We think they were parked at this point, but that's fine.

Ann-Margret and John Forsythe in Kitten with a Whip. We think they were parked at this point, but that's fine.

Two shots from 1946's The Postman Always Rings Twice with John Garfield and Lana Turner, followed by of shot of them with soon-to-be murdered Cecil Kellaway.

Two shots from 1946's The Postman Always Rings Twice with John Garfield and Lana Turner, followed by of shot of them with soon-to-be murdered Cecil Kellaway.

Jean Hagen and Sterling Hayden in 1950's The Asphalt Jungle.

Shelley Winters, looking quite lovely here, fawns over dapper William Powell during a night drive in 1949's Take One False Step.

Shelley Winters, looking quite lovely here, fawns over dapper William Powell during a night drive in 1949's Take One False Step. William Talman, James Flavin, and Adele Jergens share a tense ride in 1950's Armored Car Robbery.

William Talman, James Flavin, and Adele Jergens share a tense ride in 1950's Armored Car Robbery. William Bendix rages in 1949's The Big Steal.

William Bendix rages in 1949's The Big Steal. Frank Sinatra drives contemplatively in Young at Heart, from 1954.

Frank Sinatra drives contemplatively in Young at Heart, from 1954.

George Sanders drives Ingrid Bergman through Italy, and she returns the favor, in 1954's Viaggio in Italia.

George Sanders drives Ingrid Bergman through Italy, and she returns the favor, in 1954's Viaggio in Italia. Harold Huber, Lyle Talbot, Barbara Stanwyck and her little dog too, from 1933's Ladies They Talk About.

Harold Huber, Lyle Talbot, Barbara Stanwyck and her little dog too, from 1933's Ladies They Talk About.

Virginia Huston tells Robert Mitchum his profile should be cast in bronze in 1947's Out of the Past.

Virginia Huston tells Robert Mitchum his profile should be cast in bronze in 1947's Out of the Past. Ann Sheridan hangs onto to an intense George Raft in 1940's They Drive by Night.

Ann Sheridan hangs onto to an intense George Raft in 1940's They Drive by Night. Peggy Cummins and John Dall suddenly realize they're wearing each other's glasses in 1950's Gun Crazy, a film that famously featured a real driving sequence, though not the one above.

Peggy Cummins and John Dall suddenly realize they're wearing each other's glasses in 1950's Gun Crazy, a film that famously featured a real driving sequence, though not the one above. John Ireland and Mercedes McCambridge in 1951's The Scarf.

John Ireland and Mercedes McCambridge in 1951's The Scarf. James Mason drives an unconscious Henry O'Neill in 1949's The Reckless Moment. Hopefully they're headed to an emergency room.

James Mason drives an unconscious Henry O'Neill in 1949's The Reckless Moment. Hopefully they're headed to an emergency room. Marcello Mastroianni driving Walter Santesso, Mary Janes, and an unknown in 1960's La dolce vita.

Marcello Mastroianni driving Walter Santesso, Mary Janes, and an unknown in 1960's La dolce vita. Tony Curtis thrills Piper Laurie with his convertible in 1954's Johnny Dark.

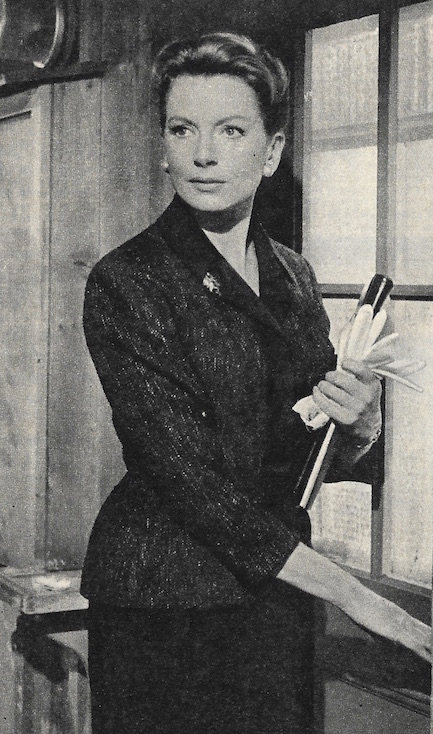

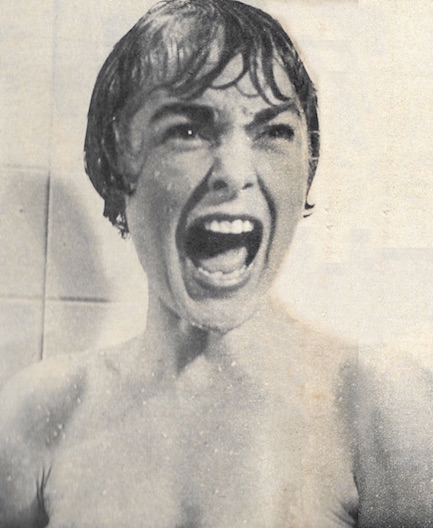

Tony Curtis thrills Piper Laurie with his convertible in 1954's Johnny Dark. Janet Leigh drives distracted by worries, with no idea she should be thinking less about traffic and cops than cross-dressing psychos in 1960's Psycho.

Janet Leigh drives distracted by worries, with no idea she should be thinking less about traffic and cops than cross-dressing psychos in 1960's Psycho. We're not sure who the passengers are in this one (the shot is from 1960's On the Double, and deals with Danny Kaye impersonating Wilfrid Hyde-White) but the driver is Diana Dors.

We're not sure who the passengers are in this one (the shot is from 1960's On the Double, and deals with Danny Kaye impersonating Wilfrid Hyde-White) but the driver is Diana Dors. Kirk Douglas scares the bejesus out of Raquel Welch in 1962's Two Weeks in Another Town. We're familiar with her reaction, which is why we're glad the Pulp Intl. girlfriends don't need to drive here in Europe.

Kirk Douglas scares the bejesus out of Raquel Welch in 1962's Two Weeks in Another Town. We're familiar with her reaction, which is why we're glad the Pulp Intl. girlfriends don't need to drive here in Europe. Robert Mitchum again, this time in the passenger seat, with Jane Greer driving (and William Bendix tailing them—already seen in panel ten), in 1949's The Big Steal. The film is notable for its many real driving scenes.

Robert Mitchum again, this time in the passenger seat, with Jane Greer driving (and William Bendix tailing them—already seen in panel ten), in 1949's The Big Steal. The film is notable for its many real driving scenes. James Mason keeps cool as Jack Elam threatens him as Märta Torén watches from the passenger seat in 1950's One Way Street.

James Mason keeps cool as Jack Elam threatens him as Märta Torén watches from the passenger seat in 1950's One Way Street. And finally, to take a new perspective on the subject, here's Bogart and Lizabeth Scott in 1947's Dead Reckoning.

And finally, to take a new perspective on the subject, here's Bogart and Lizabeth Scott in 1947's Dead Reckoning.The Company She KeepsKitten with a WhipHigh SierraWritten on the WindThe Postman Always Rings TwiceTake One False StepArmored Car RobberyThe Big StealYoung at HeartViaggio in ItaliaLadies They Talk AboutOut of the PastThey Drive by NightGun CrazyThe ScarfThe Reckless MomentLa dolce vitaJohnny DarkPsychoOn the DoubleTwo Weeks in Another TownThe Asphalt JungleThe Big StealDead Reckoningfilm noircinema

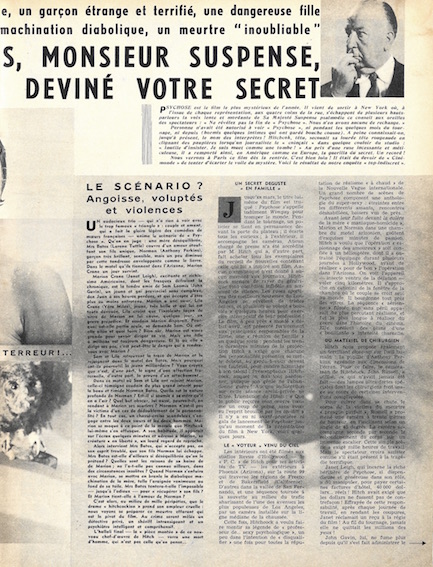

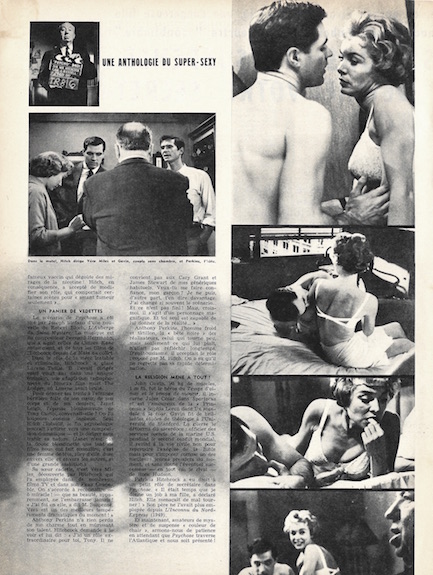

| Intl. Notebook | Mar 5 2022 |

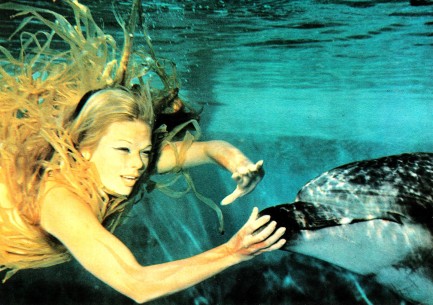

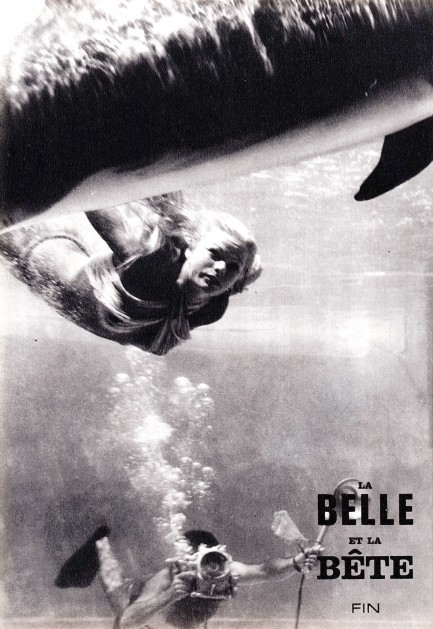

Taina Béryl and an aquatic companion get into the swim of things.

It was about time for an addition to the Pulp Intl. swim team, so above you see German actress and dancer Taina Béryl from a 1970 issue of the French magazine Moi. She joins vintage water sprites Belita, the Townhouse Aqua Maidens, Ella Raines, the synchronized swimmers of Hellzapoppin, the mermaids of Weeki Wachee Springs, and—if we want to stretch the theme—vintage drowner Christine Todd, but ups the ante with body paint and dolphin accompaniment.

The feature is called “La belle et la bête,” which means, “beauty and the beast.” Needless to say, the dolphin community was up in fins about one of their number being called a beast, and we don't blame them. Last we checked they hadn't eaten almost every living thing in the oceans. Not surprisingly, the dolphin was shunned in the magazine business after the fuss and its modeling career came to an unjust end.

Béryl appeared in nine films during her career, including 1968's Run, Psycho, Run, 1965's Spy in Your Eye, and 1963's L'inconnue de Hong Kong, aka Stranger from Hong Kong. All of those sound like fun to us. Béryl was also popular as a magazine model, scoring covers and centerfolds of publications like Ciné-Revue and Cinémonde. We have a shot of her on land, and if you want to see that just go here.

| Vintage Pulp | Dec 29 2020 |

You really don't want to wake this guy.

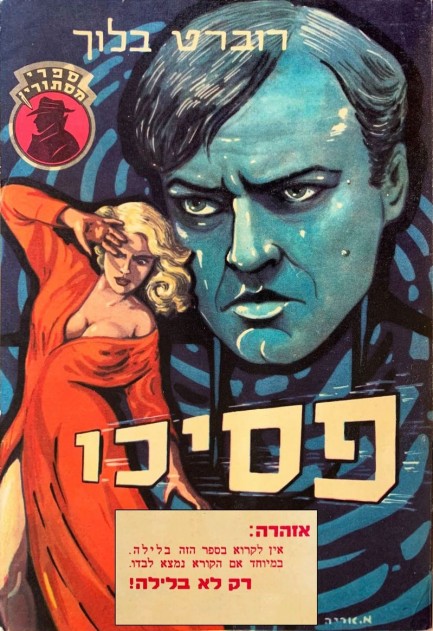

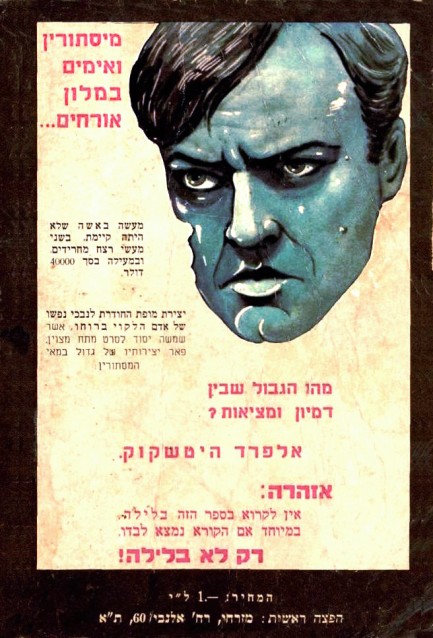

Here's an amazing piece of international pulp, a cover in Yiddish from M. Mizrahi Publishing for Robert Bloch's thriller Psycho. We recently posted a collection of Psycho covers, but we held this one back because it deserved its own moment. This was painted by an artist named Arie Moskowitz, sometimes referred to as M. Arie, who produced several more fronts we may share later. We found this one on Israeli Wikipedia, of all places, where it was posted by the National Library of Israel. It's quite a find.

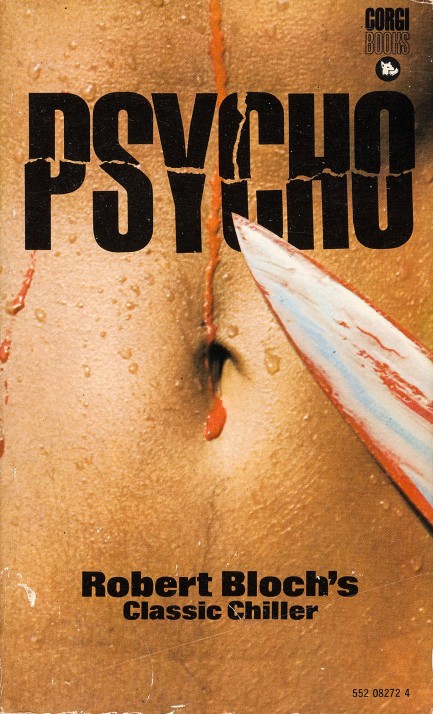

| Vintage Pulp | Oct 31 2020 |

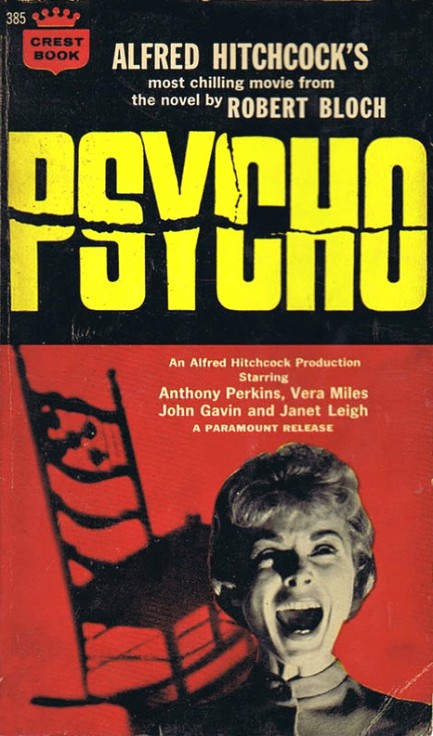

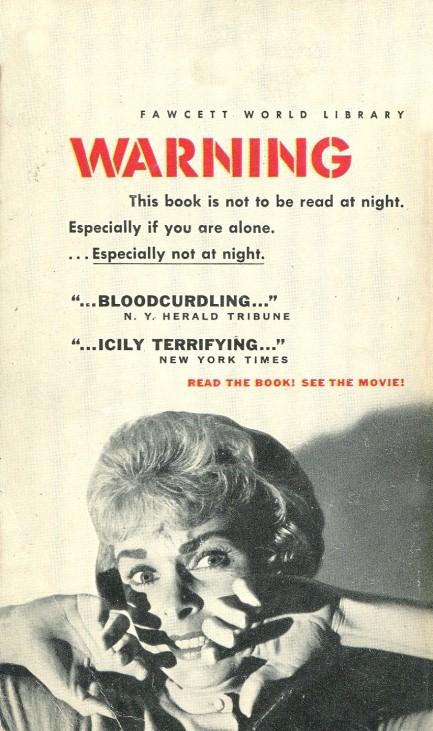

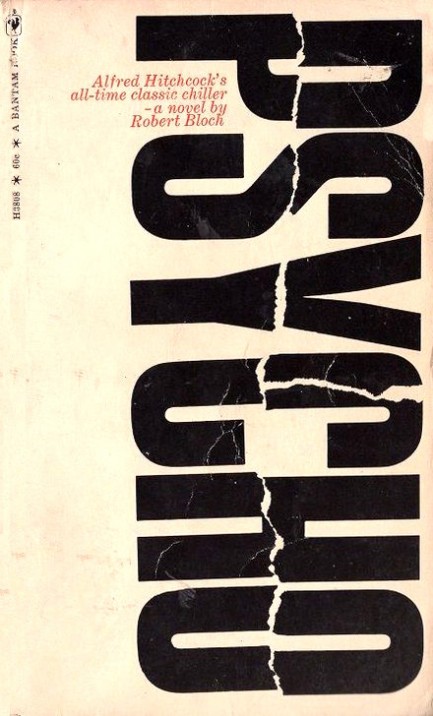

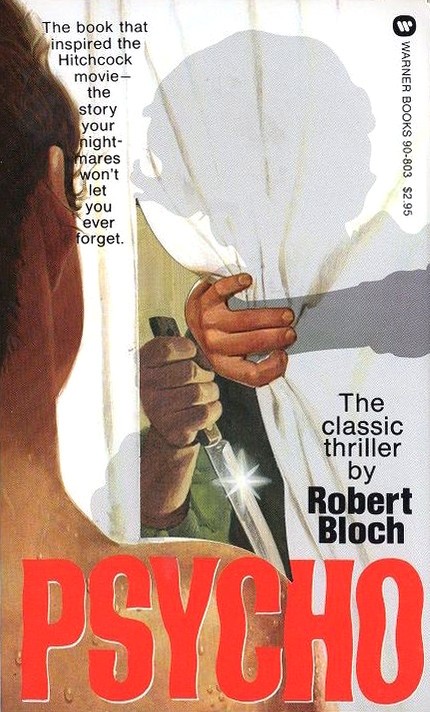

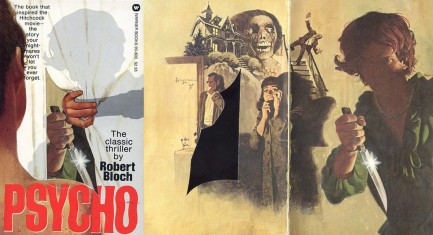

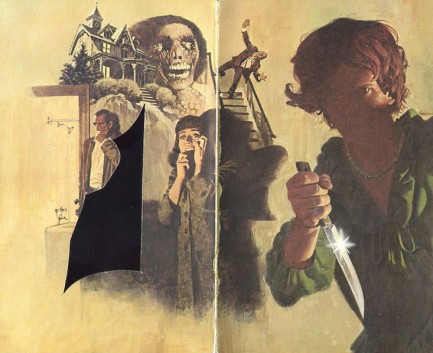

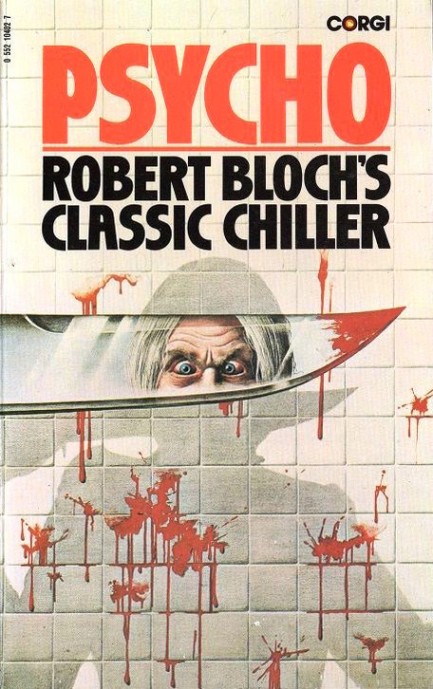

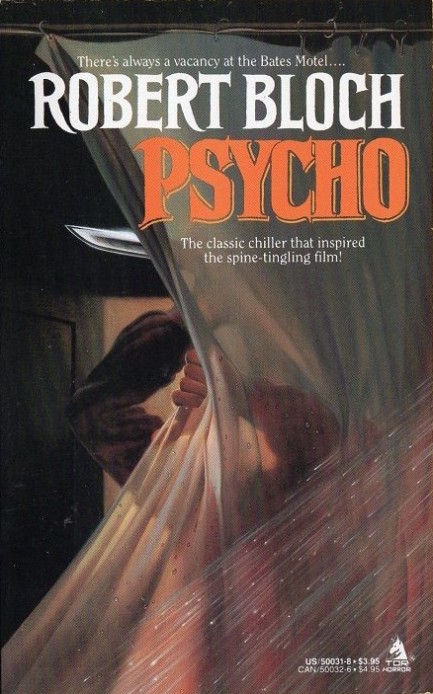

Some people need a mental health day every day.

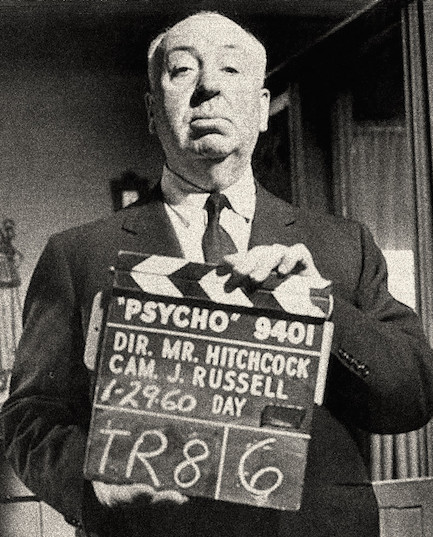

We were going to post an assortment of covers we thought were scary, but when we came across these Psycho fronts we realized they were all we needed. The creation of veteran horror author Robert Bloch and originally published in 1959, one of literature's early homicidal psychopaths remains frightening even today. When Bloch wrote Psycho the concept of psychopathy was little known in American culture, but after Alfred Hitchcock's 1960 movie adaptation, as well as the real-world Dahmers and Specks and Bundys, that naïveté evaporated. Now everyone knows psychopaths are real and live among us.

Bloch's man-child Norman Bates, a sadist and misanthrope with lust/hate feelings toward women, was able despite his dysfunctions to operate in society with a veneer of civility, and was capable of love, but only a stunted and twisted variety instilled by an emotionally violent forebear from whose shadow he could never fully escape. Sound like anybody you know? We have mostly front covers below, along with a rear cover and a nice piece of foldout art we found on the blog toomuchhorrorfiction. These are all English editions. We'll show you one or two interesting non-English covers later.

| Femmes Fatales | Mar 13 2020 |

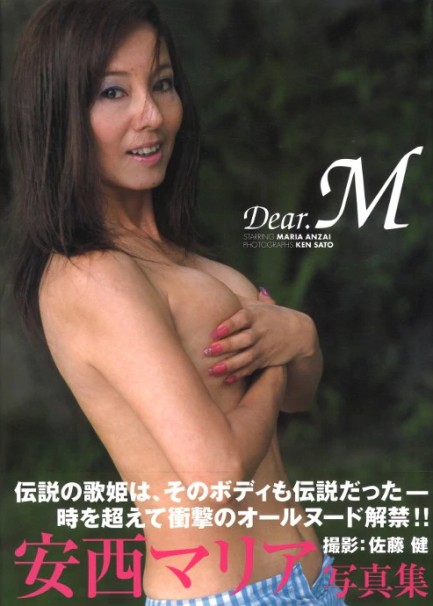

She surfed a wave that lasted four decades.

The wonderful surfing themed photo you see here shows Japanese actress, model, and singer Maria Anzai, who debuted in show business in 1973, and that year won the Japan Record Grand Prize Newcomer Award. As an actress she appeared in a handful of television shows and two movies, one of which was Rupan Sansei: Nenriki chin sakusen, which in English had the amazing title Lupin the Third: Strange Psychokinetic Strategy.

Obviously with such a slight filmography, the wave we suggest she caught isn't her film career. Nor are we referencing her music work, though she was quite popular for awhile. That leaves only her modeling. Anzai, like luminaries such as Rita Moreno and Helen Mirren, looked amazing until a very late age. The photo above appeared in 1975, when she was twenty-two, but below you see her aged fifty-plus, in two shots published in a photo book devoted entirely to her called Dear M.

The cover text says something like, “The legendary diva also had a legendary body.” We should say so. Even if you factor in a little photo retouching she looks great. She even outlasted Japan's 1970s-era censorship of pubic hair and was able to go full frontal in the new millennium. But where her beauty genes were excellent, other genes may not have been—she died only two years after Dear M. was released, victim of a heart attack. You can see another image of her next-to-last in this group of magazine covers we posted several years back.

| Hollywoodland | Jul 5 2019 |

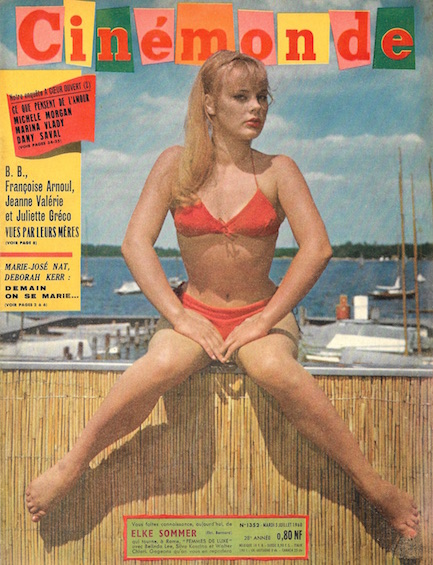

It was Elke's world. Everyone else just lived in it.

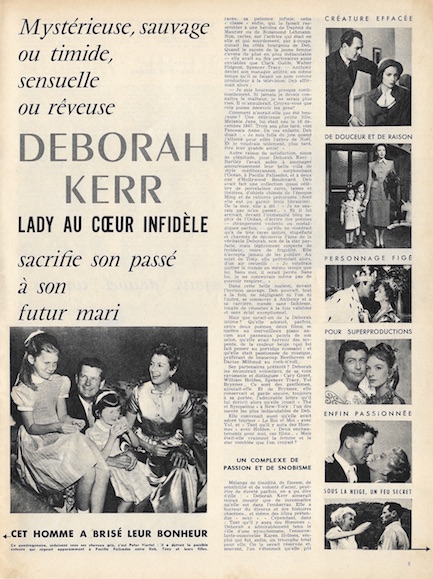

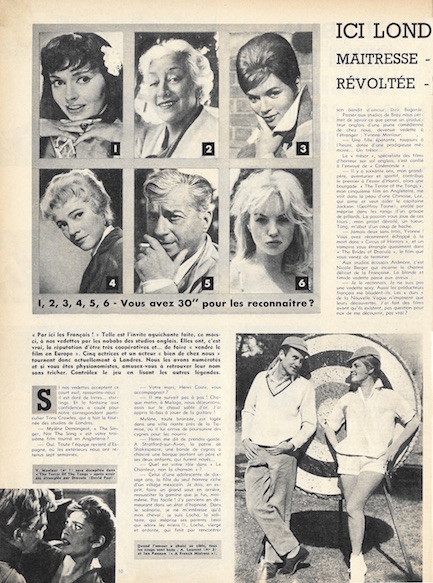

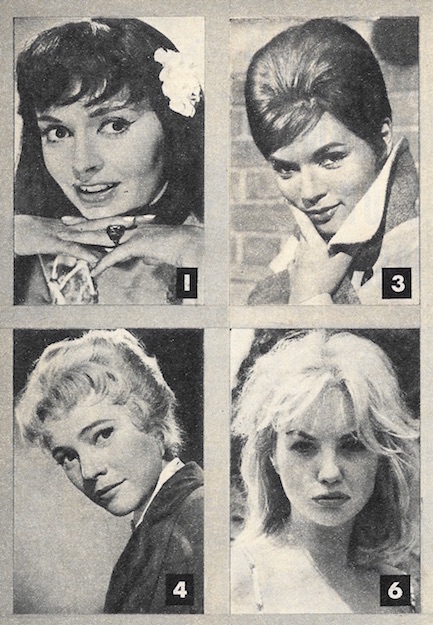

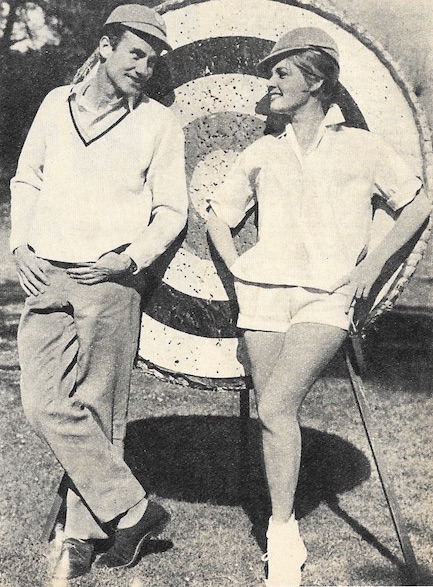

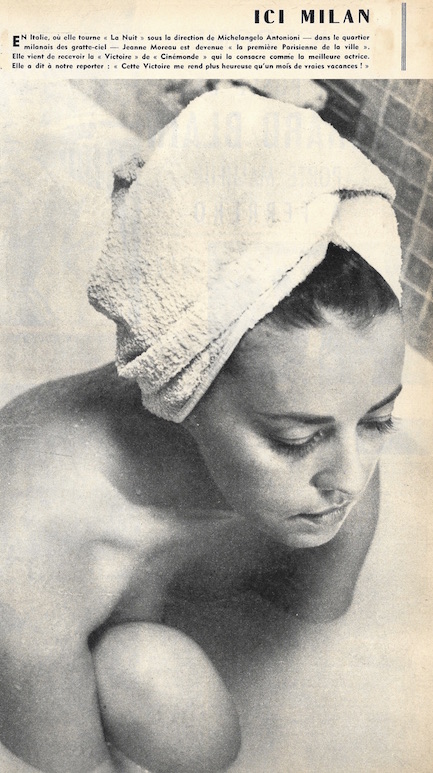

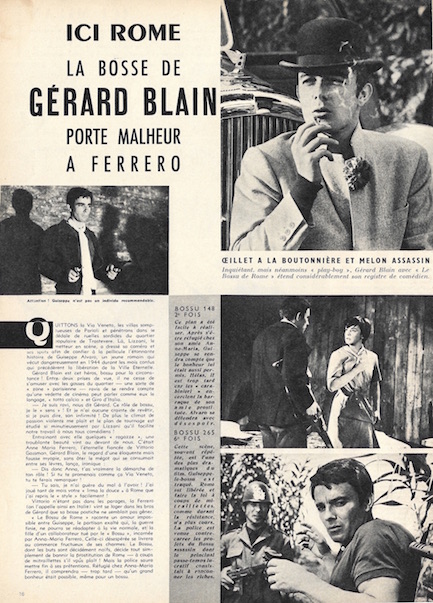

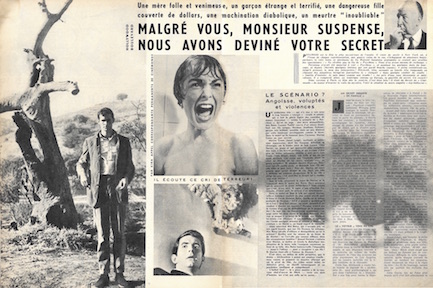

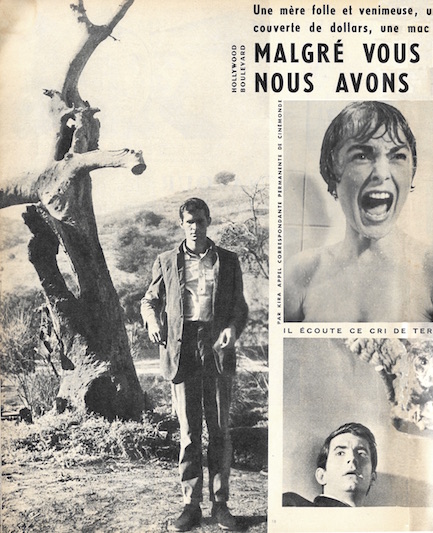

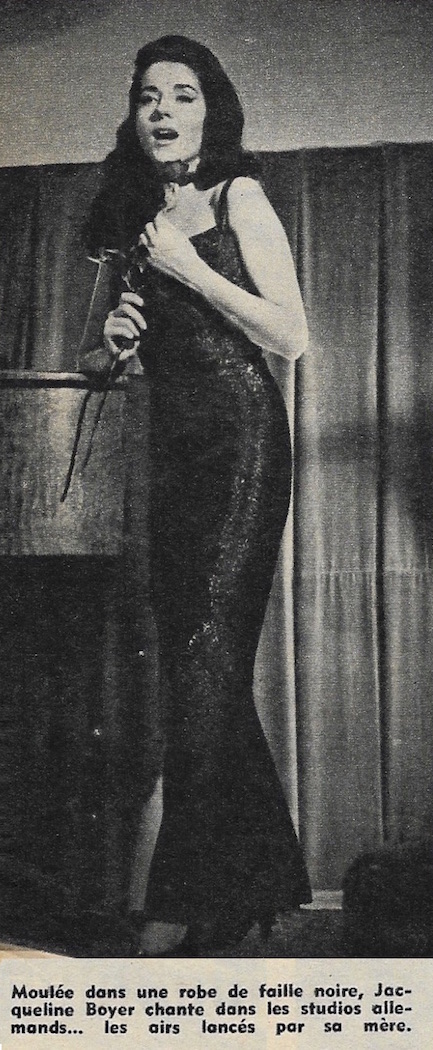

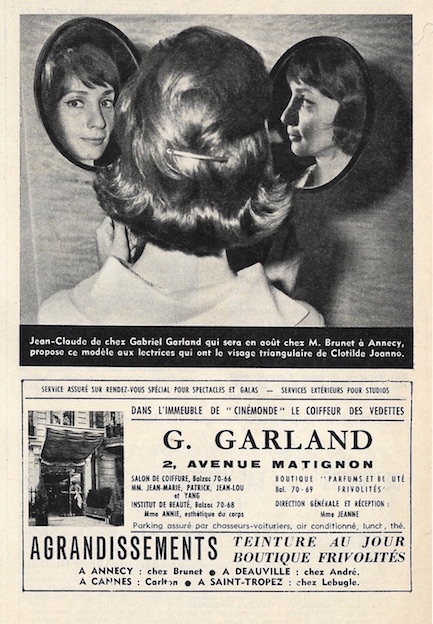

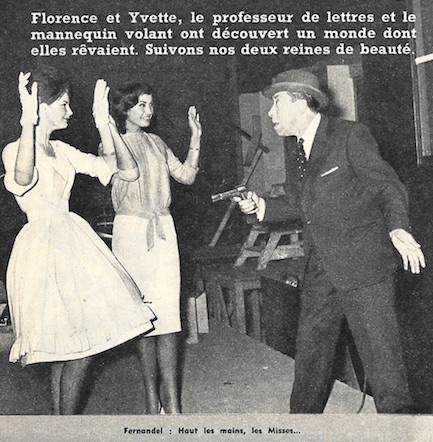

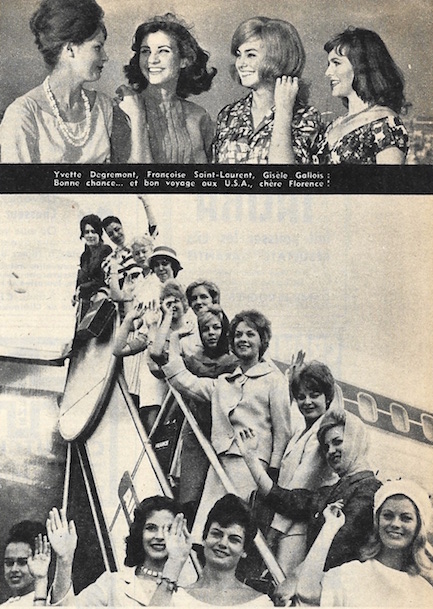

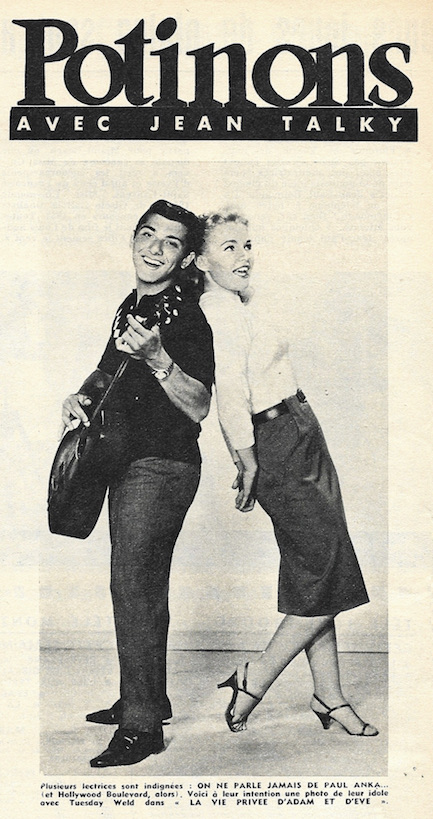

Below, another treasure from our France trip. Cinémonde magazine published today in 1960 with Elke Sommer in a summery cover shot and interior photos of Marie-José Nat, Roger Dumas, Deborah Kerr, Jeanne Moreau, and more.

| Vintage Pulp | Jan 14 2018 |

The Bates Motel offers room service with that personal touch.

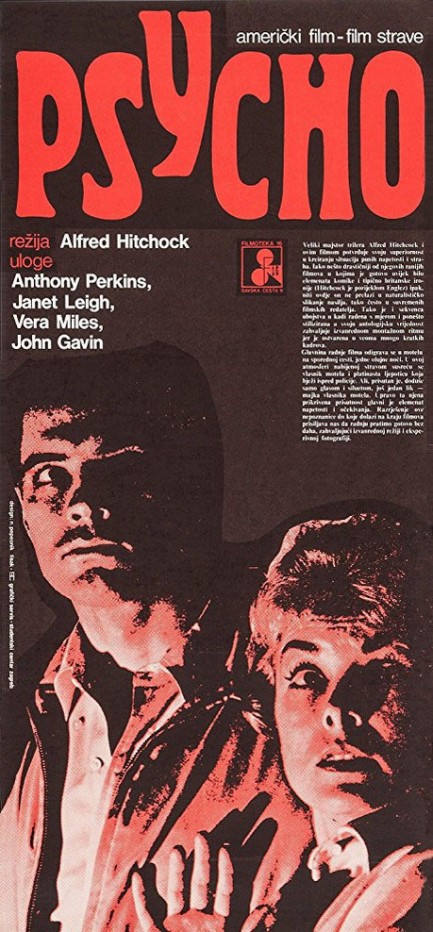

When we wrote about Psycho a while back we came across this Yugoslavian poster which we're sharing today, finally. Usually we write about films on their release dates but there isn't an exact one known for Yugoslavia. It arrived there in 1963, though, three years after its U.S. run. This two tone poster is about as low rent as it gets, but it's still effective, we think.