| Hollywoodland | Jul 17 2024 |

Actually, a great woman often has nothing but her own sheer will, but a little support never hurts. This photo shows Ava Gardner getting a boost from Burt Lancaster somewhere on Malibu Beach in 1946. It was made while they were filming The Killers, and there are several more shots from the session out there if you're inclined to look. We've shared a lot of art from The Killers, which you can see here, here, here, here, and here. And, of course, you should watch the movie.

| Vintage Pulp | May 9 2022 |

| Vintage Pulp | Mar 21 2022 |

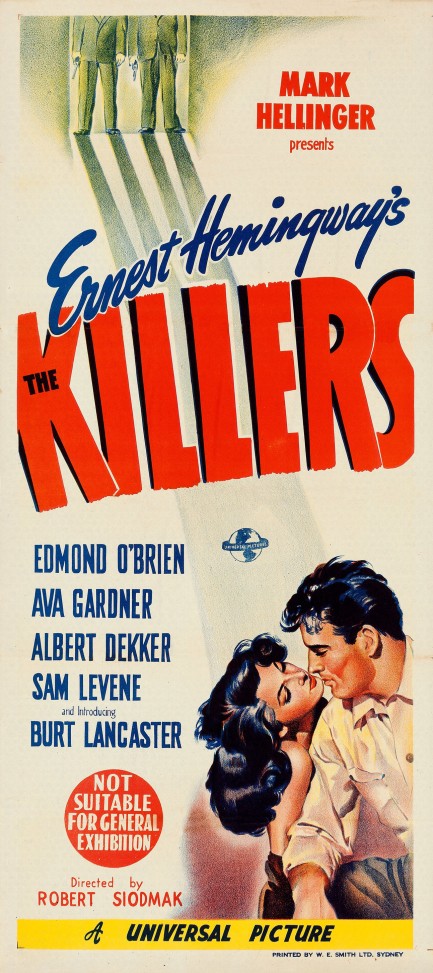

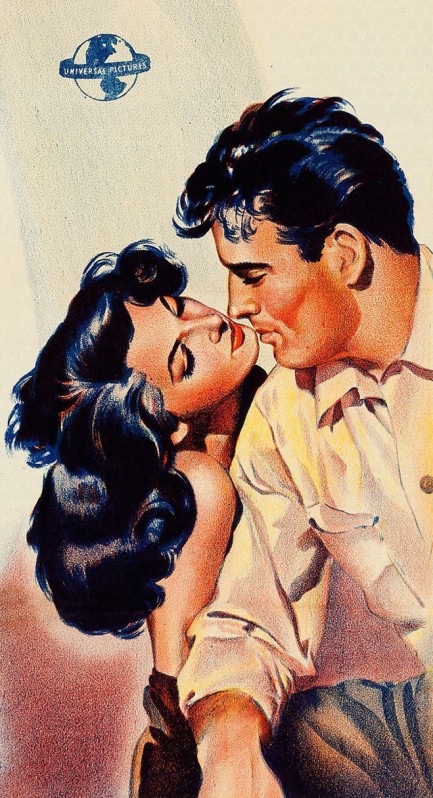

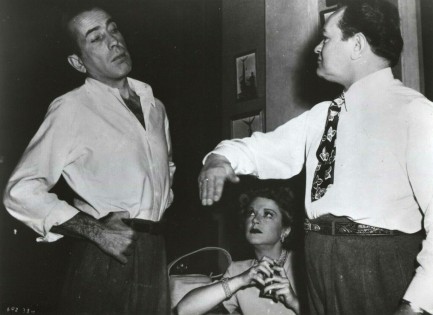

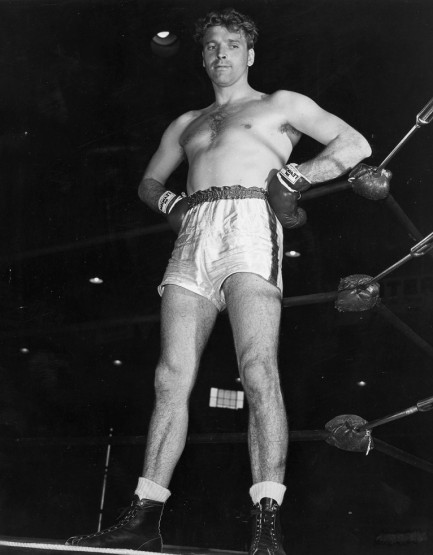

Burt Lancaster as a doomed boxer named Ole Anderson, shot dead one night by a couple of hit men, is a seminal character in film noir. He epitomizes the major characteristic of the genre, that of a person caught in dangerous circumstances beyond their control. He's so caught he never tries to run or defend himself. He lets the killers shoot him. We didn't spoil anything by telling you that—Anderson is dead ten minutes after the movie opens. Using Ernest Hemingway's short story of the same name as a starting place, The Killers takes a typical endpoint for a film noir and flips the timeline around so that the drama becomes finding out why Anderson suffered such a hopeless demise. Sunset Boulevard would pull the same trick later in visionary fashion by having the dead character actually narrate the movie. We've shown you several posters for The Killers, but this one made for the Australian market is, well, killer. Compare it to the U.S. promo here. The movie premiered in Australia today in 1947.

| Hollywoodland | May 22 2021 |

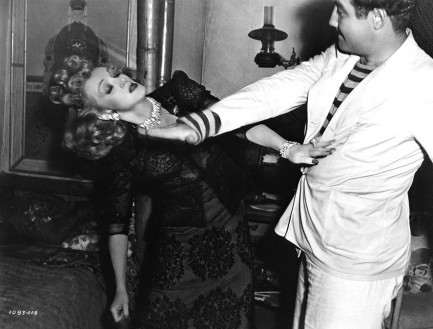

Broderick Crawford slaps Marlene Dietrich in the 1940's Seven Sinners.

Broderick Crawford slaps Marlene Dietrich in the 1940's Seven Sinners. June Allyson lets Joan Collins have it across the kisser in a promo image for The Opposite Sex, 1956.

June Allyson lets Joan Collins have it across the kisser in a promo image for The Opposite Sex, 1956. Speaking of Gilda, here's one of Glenn Ford and Rita Hayworth re-enacting the slap heard round the world. Hayworth gets to slap Ford too, and according to some accounts she loosened two of his teeth. We don't know if that's true, but if you watch the sequence it is indeed quite a blow. 100% real. We looked for a photo of it but had no luck.

Speaking of Gilda, here's one of Glenn Ford and Rita Hayworth re-enacting the slap heard round the world. Hayworth gets to slap Ford too, and according to some accounts she loosened two of his teeth. We don't know if that's true, but if you watch the sequence it is indeed quite a blow. 100% real. We looked for a photo of it but had no luck. Don't mess with box office success. Ford and Hayworth did it again in 1952's Affair in Trinidad.

Don't mess with box office success. Ford and Hayworth did it again in 1952's Affair in Trinidad. All-time film diva Joan Crawford gets in a good shot on Lucy Marlow in 1955's Queen Bee.

All-time film diva Joan Crawford gets in a good shot on Lucy Marlow in 1955's Queen Bee. The answer to the forthcoming question is: She turned into a human monster, that's what. Joan Crawford is now on the receiving end, with Bette Davis issuing the slap in Whatever Happened to Baby Jane? Later Davis kicks Crawford, so the slap is just a warm-up.

The answer to the forthcoming question is: She turned into a human monster, that's what. Joan Crawford is now on the receiving end, with Bette Davis issuing the slap in Whatever Happened to Baby Jane? Later Davis kicks Crawford, so the slap is just a warm-up. Mary Murphy awaits the inevitable from John Payne in 1955's Hell's Island.

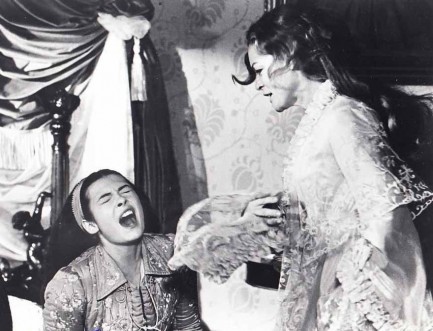

Mary Murphy awaits the inevitable from John Payne in 1955's Hell's Island. Romy Schneider slaps Sonia Petrova in 1972's Ludwig.

Romy Schneider slaps Sonia Petrova in 1972's Ludwig. Lauren Bacall lays into Charles Boyer in 1945's Confidential Agent and garnishes the slap with a brilliant snarl.

Lauren Bacall lays into Charles Boyer in 1945's Confidential Agent and garnishes the slap with a brilliant snarl. Iconic bombshell Marilyn Monroe drops a smart bomb on Cary Grant in the 1952 comedy Monkey Business.

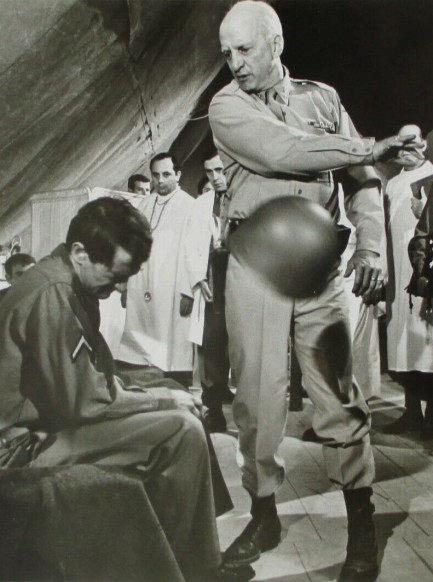

Iconic bombshell Marilyn Monroe drops a smart bomb on Cary Grant in the 1952 comedy Monkey Business. This is the most brutal slap of the bunch, we think, from 1969's Patton, as George C. Scott de-helmets an unfortunate soldier played by Tim Considine.

This is the most brutal slap of the bunch, we think, from 1969's Patton, as George C. Scott de-helmets an unfortunate soldier played by Tim Considine. A legendary scene in filmdom is when James Cagney shoves a grapefruit in Mae Clark's face in The Public Enemy. Is it a slap? He does it pretty damn hard, so we think it's close enough. They re-enact that moment here in a promo photo made in 1931.

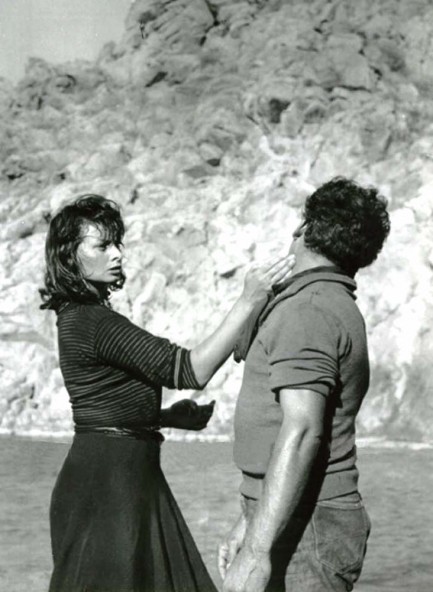

A legendary scene in filmdom is when James Cagney shoves a grapefruit in Mae Clark's face in The Public Enemy. Is it a slap? He does it pretty damn hard, so we think it's close enough. They re-enact that moment here in a promo photo made in 1931. Sophia Loren gives Jorge Mistral a scenic seaside slap in 1957's Boy on a Dolphin.

Sophia Loren gives Jorge Mistral a scenic seaside slap in 1957's Boy on a Dolphin. Victor Mature fails to live up to his last name as he slaps Lana Turner in 1954's Betrayed.

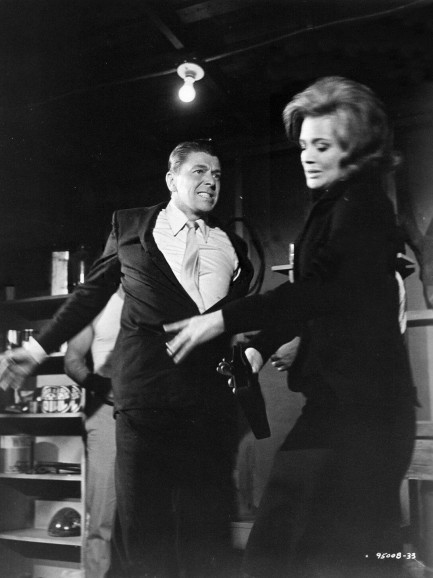

Victor Mature fails to live up to his last name as he slaps Lana Turner in 1954's Betrayed. Ronald Reagan teaches Angie Dickinson how supply side economics work in 1964's The Killers.

Ronald Reagan teaches Angie Dickinson how supply side economics work in 1964's The Killers. Marie Windsor gets in one against Mary Castle from the guard position in an episode of television's Stories of the Century in 1954. Windsor eventually won this bout with a rear naked choke.

Marie Windsor gets in one against Mary Castle from the guard position in an episode of television's Stories of the Century in 1954. Windsor eventually won this bout with a rear naked choke. It's better to give than receive, but sadly it's Bette Davis's turn, as she takes one from Dennis Morgan in In This Our Life, 1942.

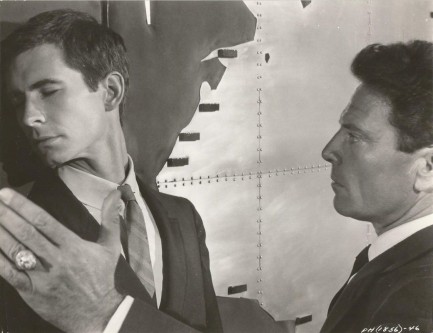

It's better to give than receive, but sadly it's Bette Davis's turn, as she takes one from Dennis Morgan in In This Our Life, 1942. Anthony Perkins and Raf Vallone dance the dance in 1962's Phaedra, with Vallone taking the lead.

Anthony Perkins and Raf Vallone dance the dance in 1962's Phaedra, with Vallone taking the lead. And he thought being inside the ring was hard. Lilli Palmer nails John Garfield with a roundhouse right in the 1947 boxing classic Body and Soul.

And he thought being inside the ring was hard. Lilli Palmer nails John Garfield with a roundhouse right in the 1947 boxing classic Body and Soul. 1960's Il vigile, aka The Mayor, sees Vittorio De Sica rebuked by a member of the electorate Lia Zoppelli. She's more than a voter in this—she's also his wife, so you can be sure he deserved it.

1960's Il vigile, aka The Mayor, sees Vittorio De Sica rebuked by a member of the electorate Lia Zoppelli. She's more than a voter in this—she's also his wife, so you can be sure he deserved it. Brigitte Bardot delivers a not-so-private slap to Dirk Sanders in 1962's Vie privée, aka A Very Private Affair.

Brigitte Bardot delivers a not-so-private slap to Dirk Sanders in 1962's Vie privée, aka A Very Private Affair. In a classic case of animal abuse. Judy Garland gives cowardly lion Bert Lahr a slap on the nose in The Wizard of Oz. Is it his fault he's a pussy? Accept him as he is, Judy.

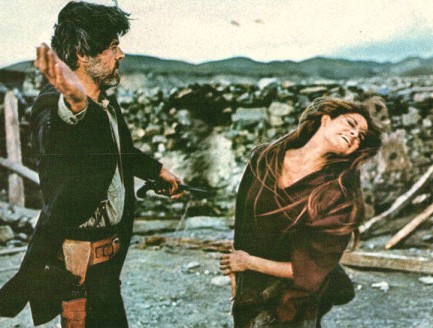

In a classic case of animal abuse. Judy Garland gives cowardly lion Bert Lahr a slap on the nose in The Wizard of Oz. Is it his fault he's a pussy? Accept him as he is, Judy. Robert Culp backhands Raquel Welch in 1971's Hannie Caudler.

Robert Culp backhands Raquel Welch in 1971's Hannie Caudler. And finally, Laurence Harvey dares to lay hands on the perfect Kim Novak in Of Human Bondage.

And finally, Laurence Harvey dares to lay hands on the perfect Kim Novak in Of Human Bondage. | Femmes Fatales | May 4 2019 |

| Vintage Pulp | Feb 1 2017 |

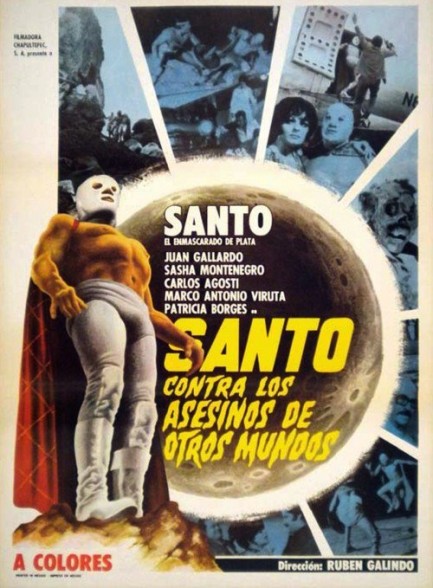

We were dubious toward Santo when we learned of his movies, but after screening three features the guy has really grown on us. So last night we watched Santo contra los asesinos de otros mundos, which was known in English as Santo vs. The Killers from Other Worlds. You know the basics—Santo is a Mexican luchador who is also an ace international crimefighter. Which is convenient, because an evil mastermind named Malkosh is demanding a fortune in gold bars from the Mexican government or he'll unleash a monster on the populace. This terrifying blob, which in the script has been somehow derived from moon rocks, in reality is three guys huddled under a giant shammy. Doubtless bumping heads and asses while crabwalking under this thing, the poor guys move at about the same speed as traffic in central Mexico City. But no matter—the blob is a whiz at triangulation, and its victims are agility challenged. Whoever it chases inevitably finds himself or herself trapped and, after futilely heaving staplers and coffee cups, consumed down to a skeletal state.

The rest of the film tracks Santo's efforts to find Malkosh's partner Licur, who has imprisoned a Professor Bernstein, the only person on Earth who knows how to corral the lunar abomination busily scuttling across the landscape. Locating Licur involves a bit of Holmesian deduction, at which point Santo gains access to the top secret high security lair by scaling a low wall. In the subsequent fistfights, he's ferociously pounded about his face and semi-soft body, yet his gimp mask never slips and his whorehouse drapes never rip. Finally he squares off against Licur himself, who proves to be no match, and at that point all that's left is to defeat the beast, now about the size of a Winnebago. We'll leave the last bit as a surprise, but suffice to say Santo is always one step ahead. In the end, the film was another satisfying outing, with all the hallmarks of the series—terrible dialogue, poorly staged fights, truly atrocious acting, and a script conceived during a blinding mezcal bender. What's not to love? Queue it. Watch it. Santo contra los asesinos de otros mundos premiered in Mexico today in 1973.

You got anything to eat around here? I'm famished.

| Vintage Pulp | Aug 28 2011 |

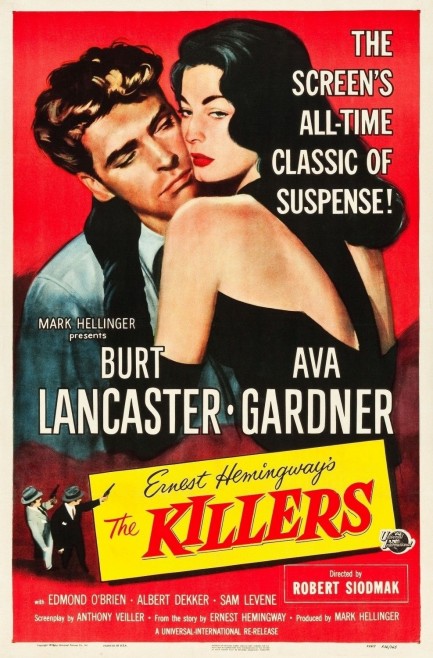

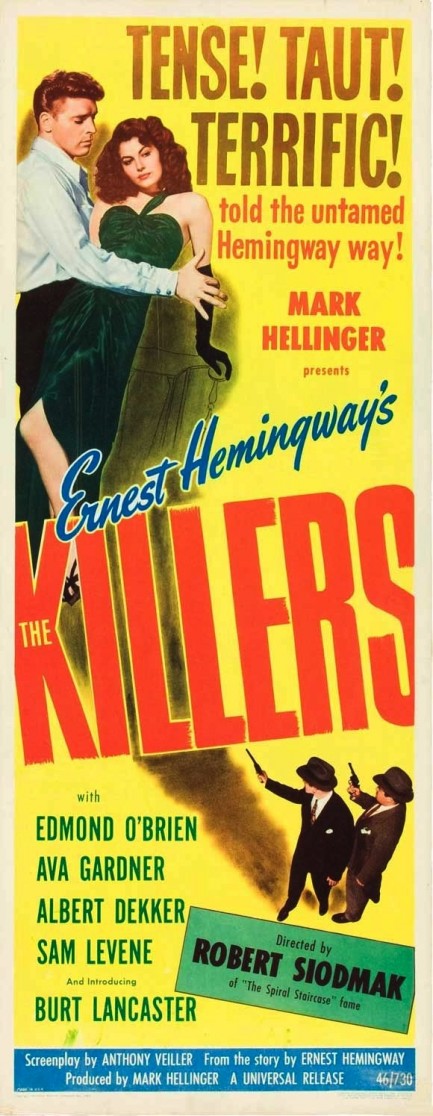

Above, a poster for Robert Siodmak’s Oscar nominated film noir The Killers. Adapted from a short story by Ernest Hemingway about an ex-boxer who meekly accepts his own murder for reasons that only become clear after a detailed investigation by an insurance adjuster, this was the film that gave us the great Burt Lancaster. Why did he let himself be murdered? Well, Ava Gardner had something to do with it. You can see the unusual French poster here, and the Swedish poster here. The Killers opened in the U.S. today in 1946.

| Vintage Pulp | Apr 3 2010 |

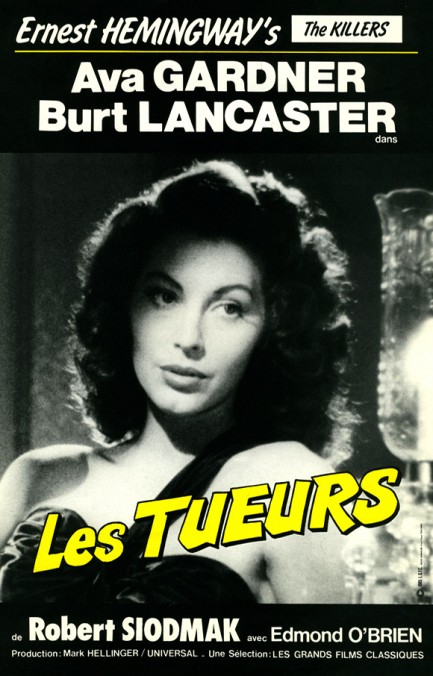

Above is an unusual one-sheet for Robert Siodmak’s 1946 film noir Les Tueurs, aka The Killers, with Burt Lancaster and Ava Gardner. You may remember we showed you the colorful Swedish poster last year. This rather hazy French effort is unusual because it features a photo of one of the stars, which is a promotional technique that wouldn’t become popular until decades later, when retouched (later digitally tweaked) photography replaced handpainted images, forever to the detriment of the art world. We’ve talked about this before, and we still have the same question. Namely, what is it inside of us that made us divorce art from commerce? We’ve embraced the soulless in every form of promotional art from movie posters to book covers to billboards. Is it simply about money? Does capitalism drive us inexorably toward an artless pursuit of profit? We have our theories, but what do you think? Or is this a little too much to be dumping on you on a spring Saturday? Right, we can take a hint. Les Tueurs premiered in Paris today in 1947.

| Vintage Pulp | Sep 29 2009 |

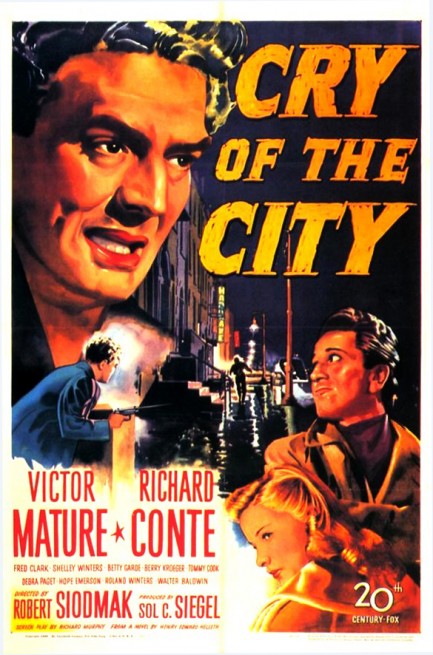

You can’t explore film noir without getting acquainted with director Robert Siodmak. We mentioned him before when we showed you the Swedish promo art for his great film The Killers, and today we have the U.S. poster for his also brilliant Cry of the City. The story involves two friends who both grew up in good families, but ended up on opposite sides of the law—one as a cop, the other as a criminal.

Victor Mature plays the cop, and we have to say, we wish he hadn’t gone on to do all those sword and sandal epics, because we kept picturing him covered with bronzer, splitting Philistines’ heads with the jawbone of an ass. But his performance here is good, a perfect counterbalance to the intense Richard Conte’s ailing crook, who opens the film wounded in a hospital bed.

Conte eventually escapes to track down the real perpetrator of a jewel heist the police have pinned on him. After a few twists and turns, he finds the real thief, but in noir, you can't buy off fate even with a last act of selflessness. Conte is still a bad man, and he's still gotta pay the piper. Cry of the City premiered in the U.S today in 1948.

| Vintage Pulp | Mar 7 2009 |

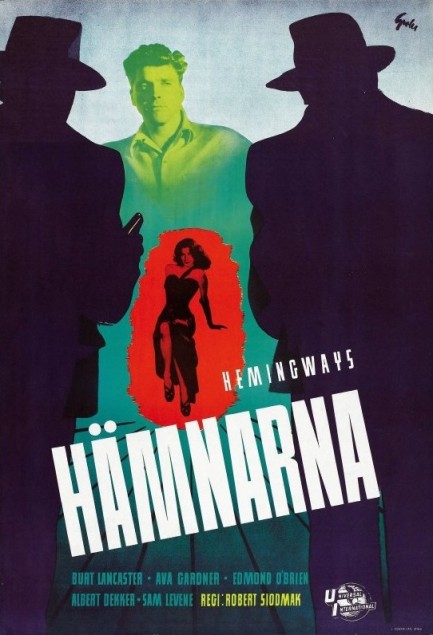

Here’s a colorful Swedish one sheet for The Killers, which is considered one of the most important noirs. Inspired by an Ernest Hemingway short story, and helmed by director Robert Siodmak, the movie opens with an unresisting Burt Lancaster being snuffed by two hit men, then follows an insurance investigator as he tries to figure out what possibly could have happened in this man’s life that would make him virtually offer himself to his murderers. All roads lead—as all roads must—to the femme fatale. In this case it’s the magical Ava Gardner, in her first starring role as the hard-as-nails Kitty Collins. The art here effectively tells the story of the film in a snapshot—we see Burt beset by his two killers as Ms. Gardner seems to burn in his breast. That pretty much sums it up. The film was a smash hit, and it remains a must-see. It first played in Stockholm today, in 1947.