Directly off the boat and immediately into trouble.

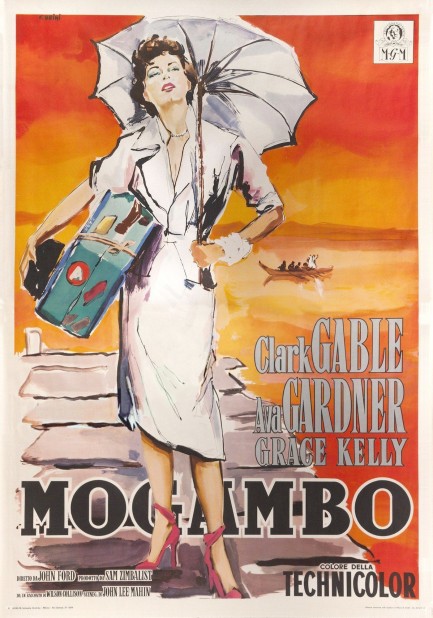

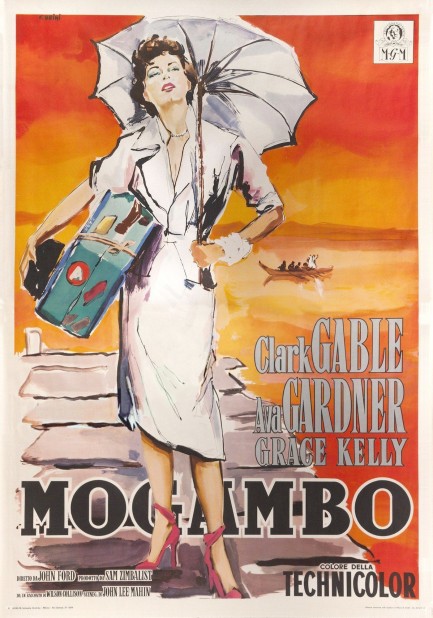

We chose the header for this post because there's a movie called White Mischief, which we watched recently, about Brits in Africa, and it has an amusing line where a character surveys the morning and says, “Oh God, not another fucking beautiful day.” The two pieces of Italian promo art above for the set-in-Africa movie Mogambo might make you say, “Oh God, not another fucking beautiful Italian poster.”

These were painted by Ercole Brini, who we've never featured before but who is another of the many virtuosic artists from Italy that toiled for the movie studios. Whenever we think about the sad loss of painted cinematic poster art, the Italians are who come to our minds. We just don't think there's any doubt at this point—they were the best. Not that it's a competition. Amazing posters with interestingly local aesthetic attributes came from everywhere.

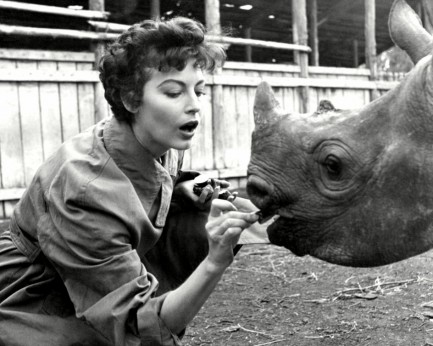

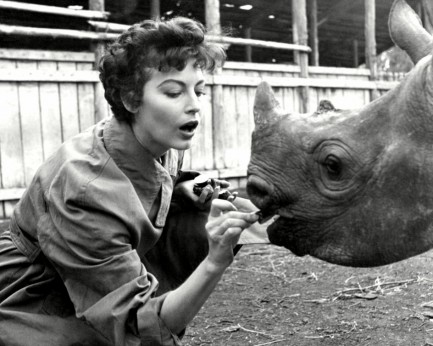

We'll try to feature more from Brini later, and if you're curious about Mogambo it's—of course—another movie about Africa turning various white northerners into cynical, shambling husks of their supposedly better former selves. Those husks are Clark Gable, Ava Gardner, and Grace Kelly. It opened in the U.S. in 1953 and premiered in Italy this week in 1954. Have a look here if you want to know more, and maybe here.

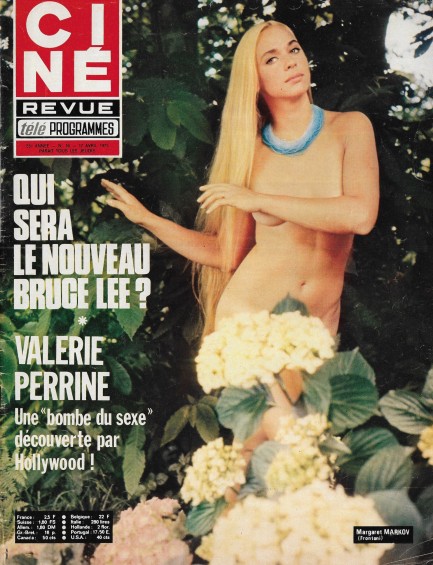

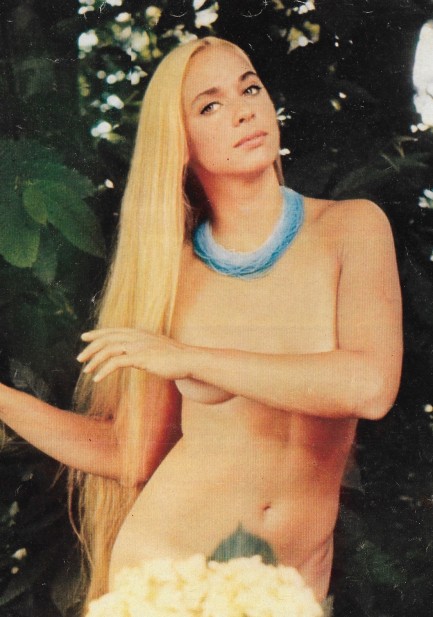

Markov plants vivid ideas in readers' heads.

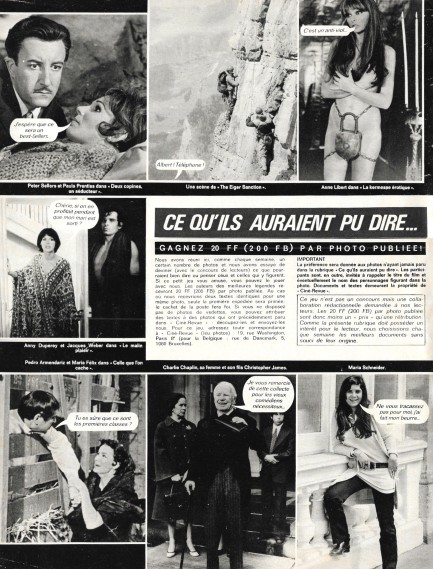

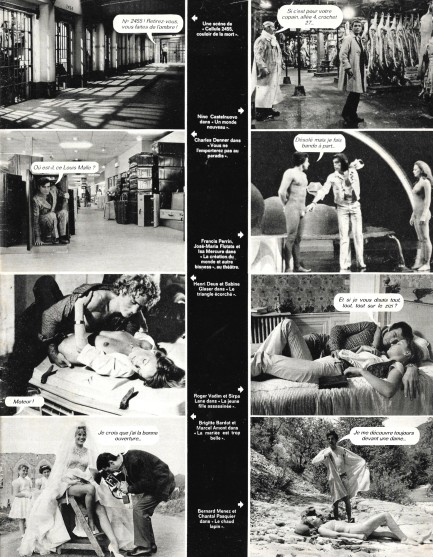

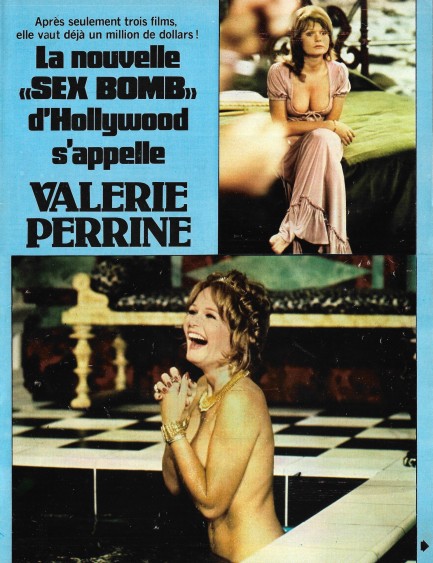

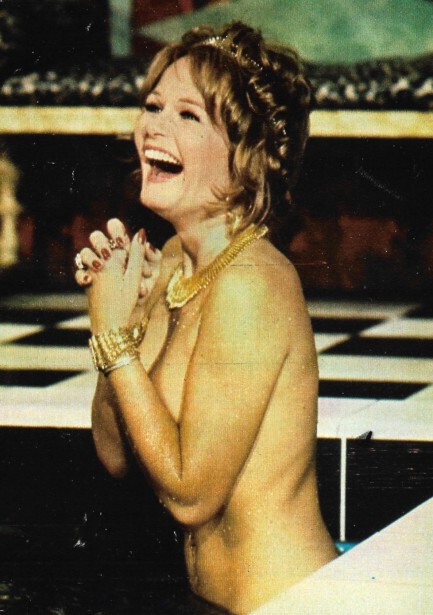

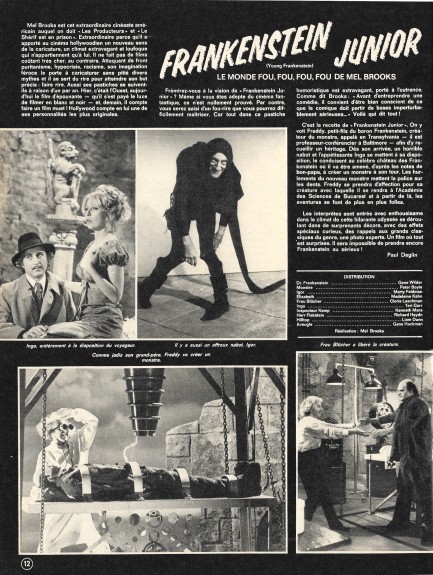

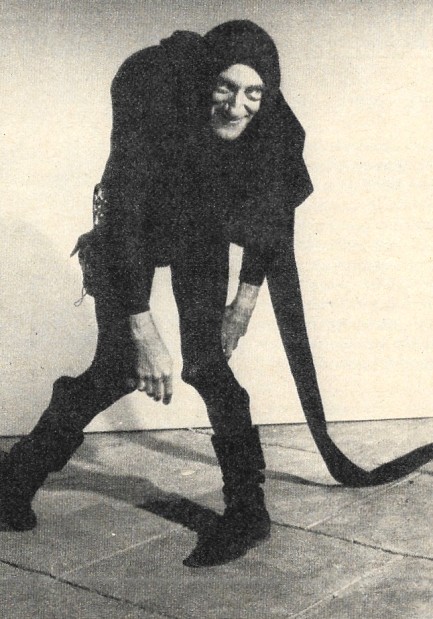

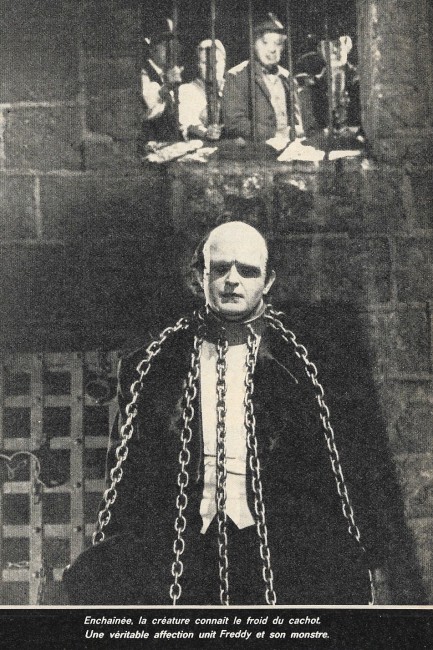

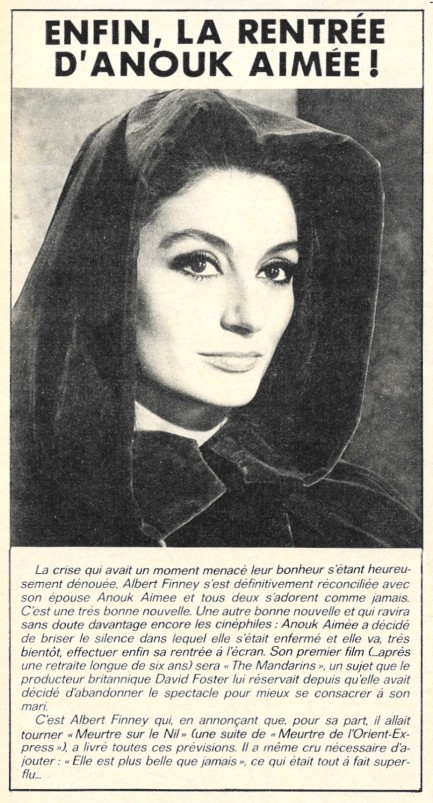

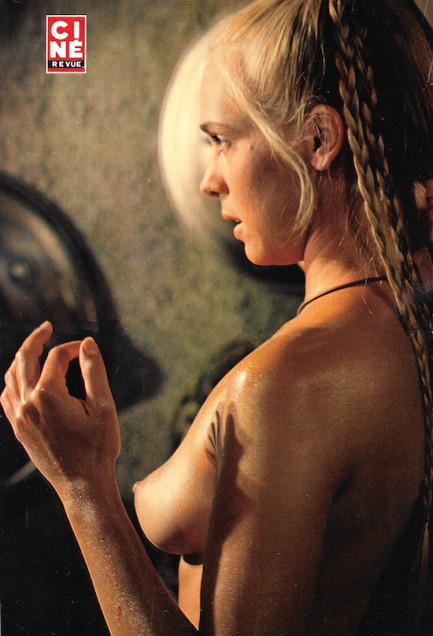

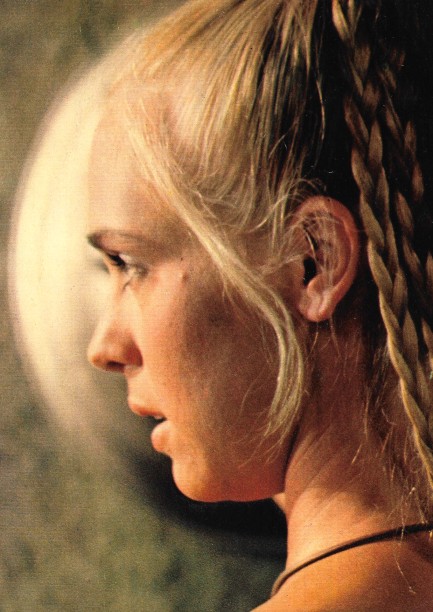

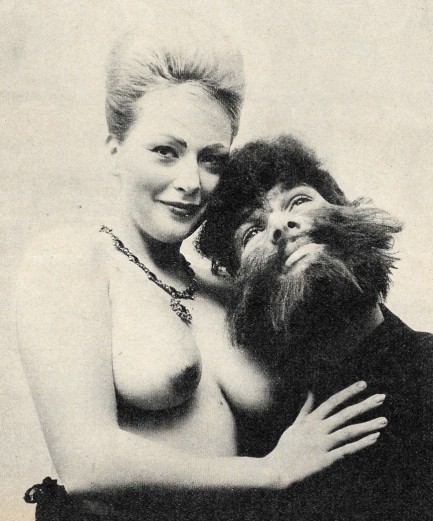

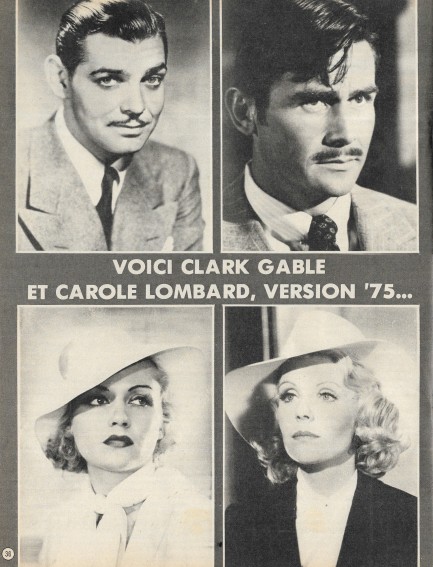

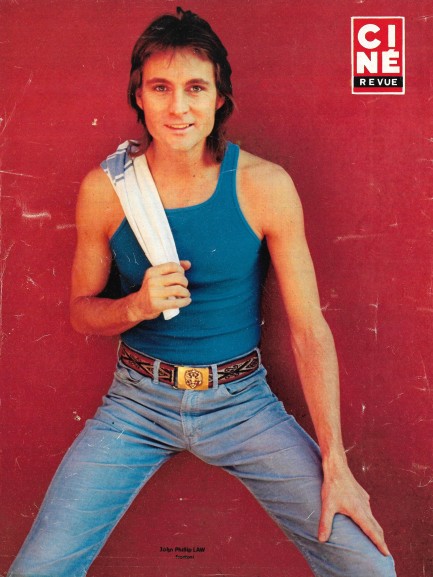

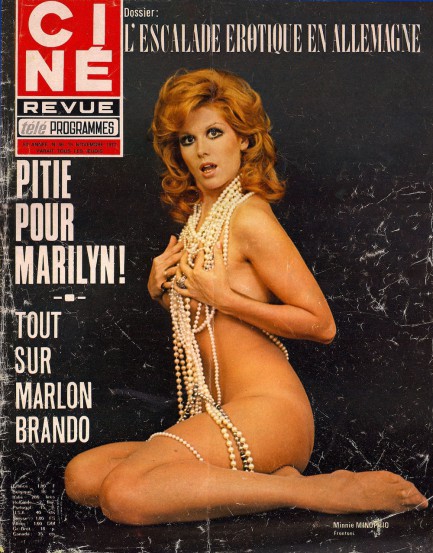

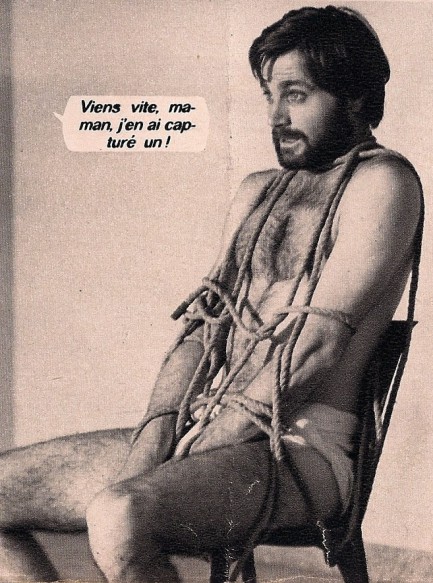

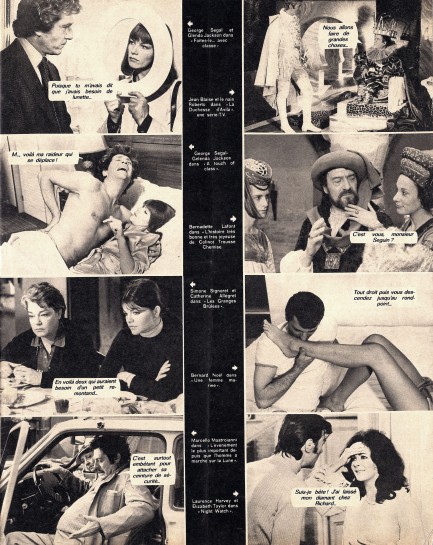

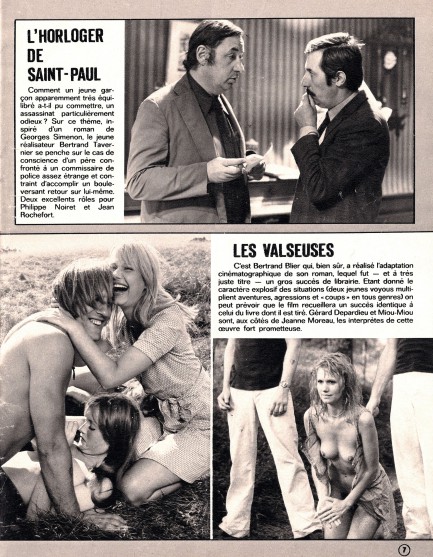

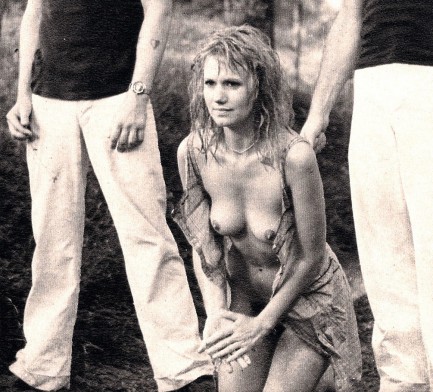

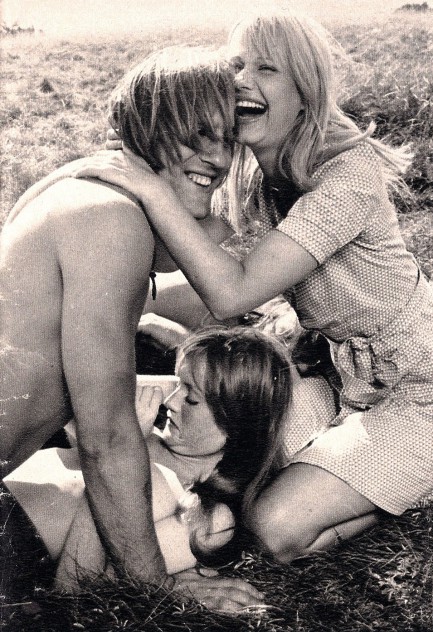

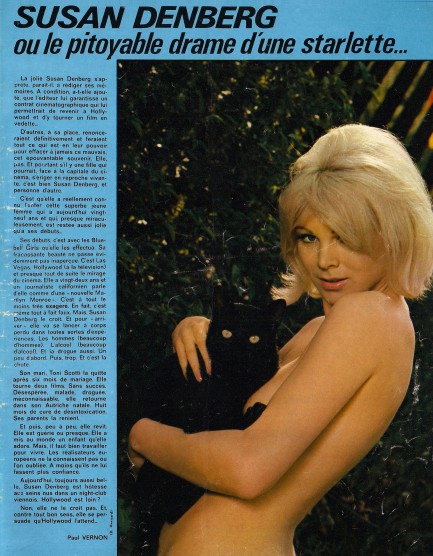

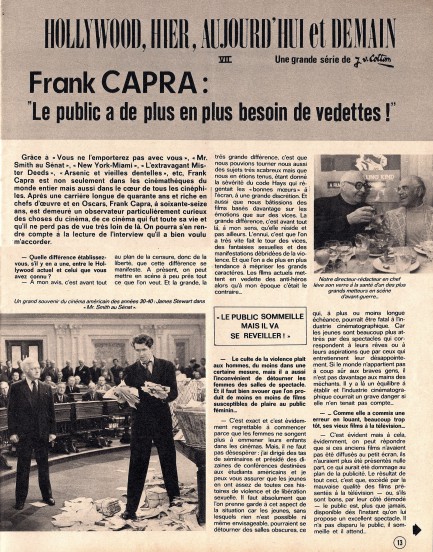

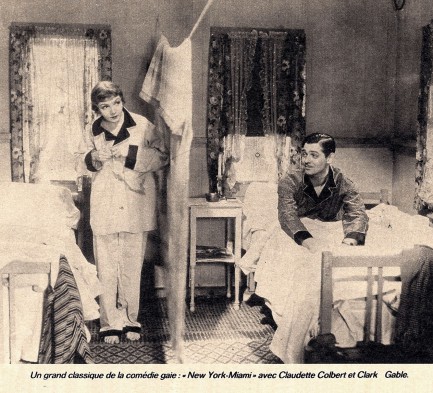

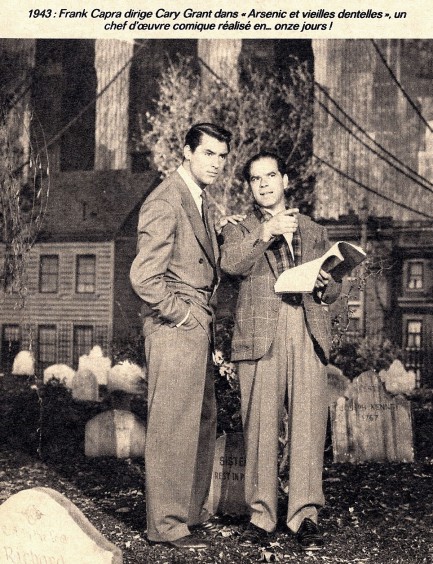

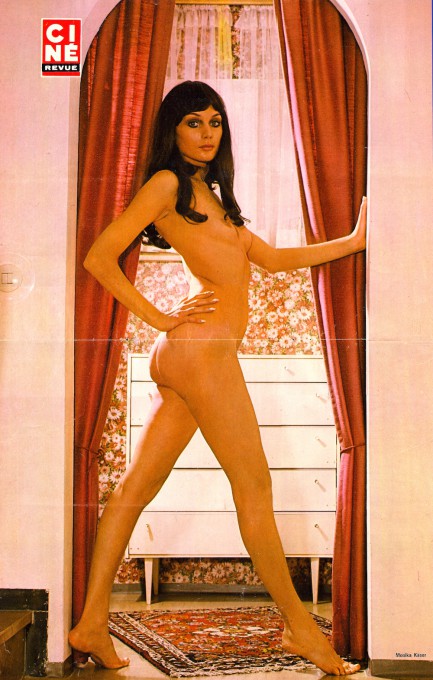

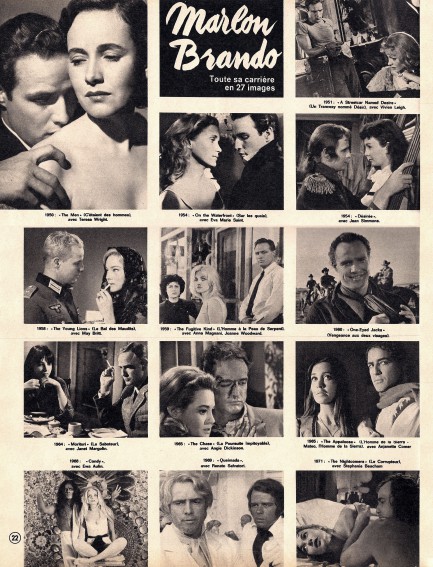

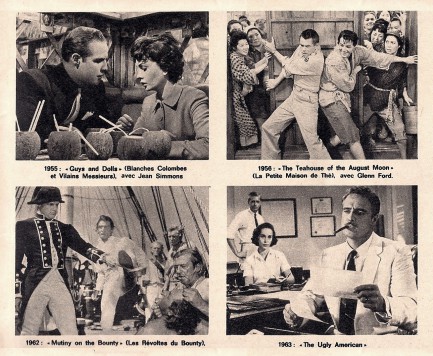

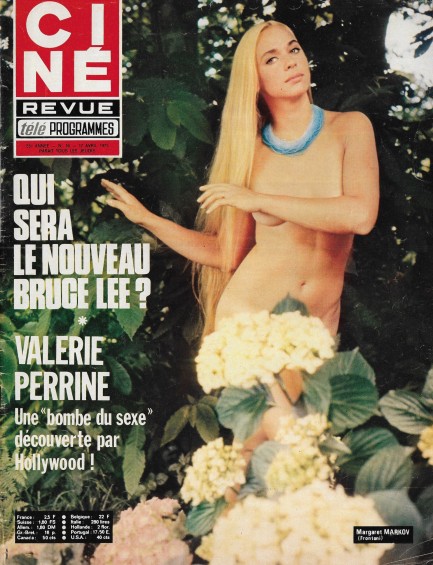

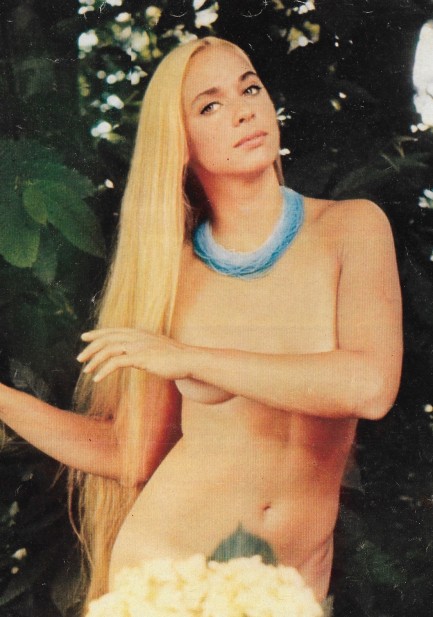

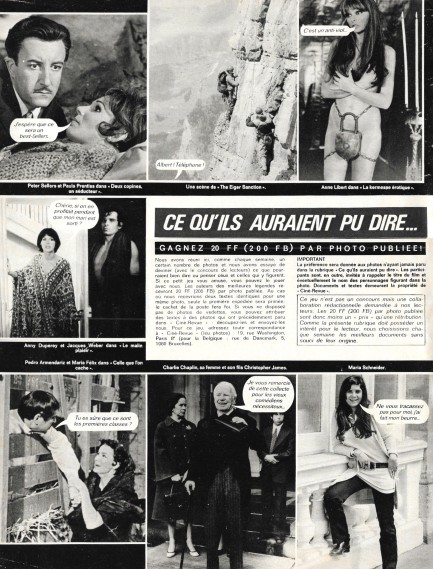

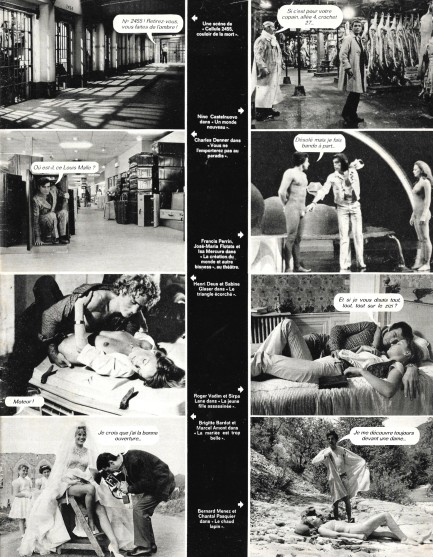

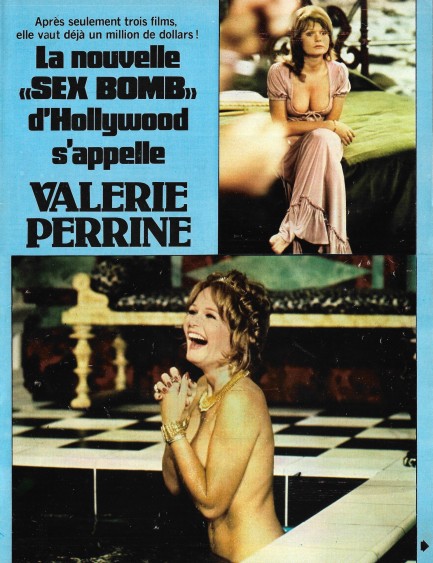

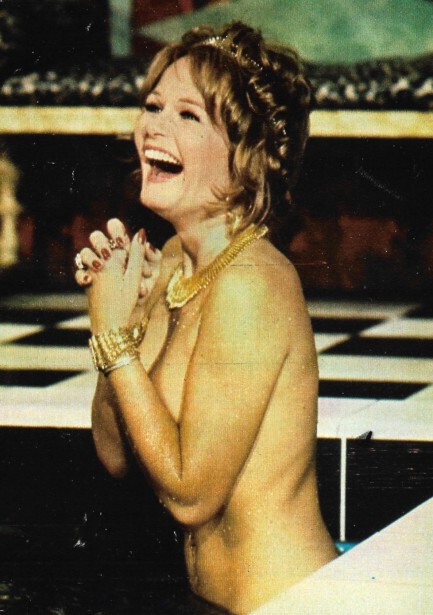

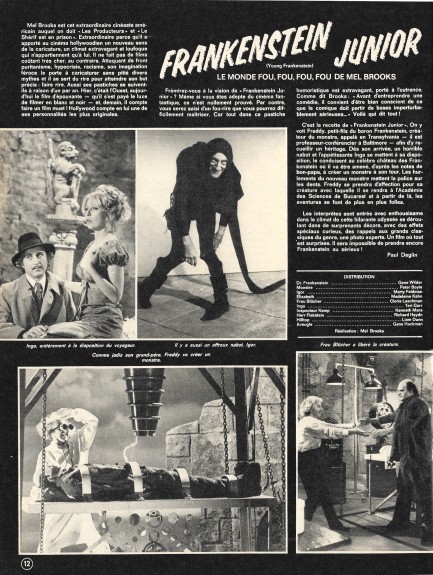

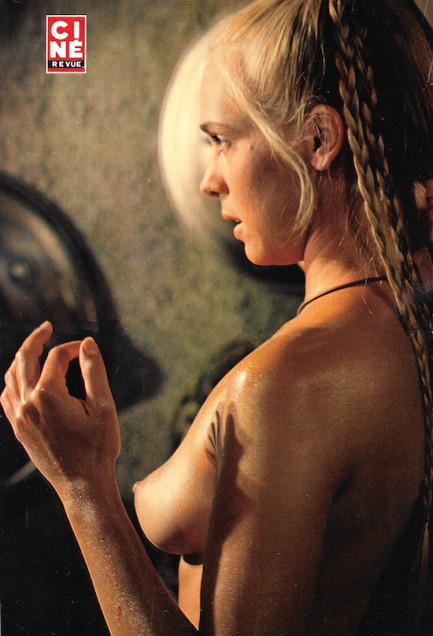

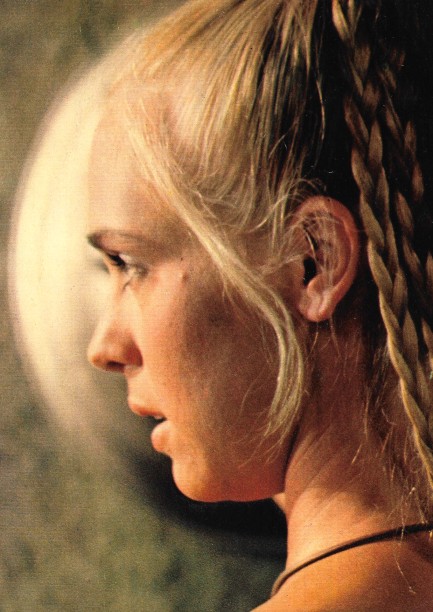

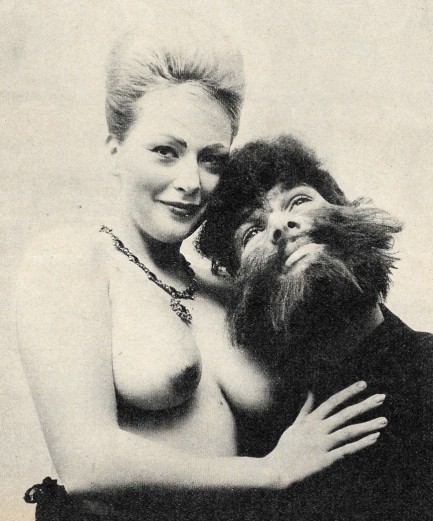

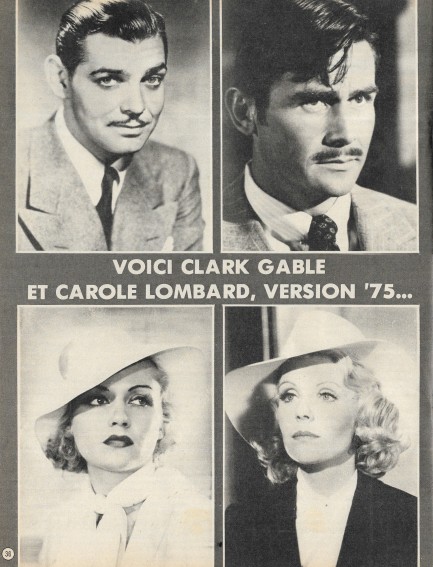

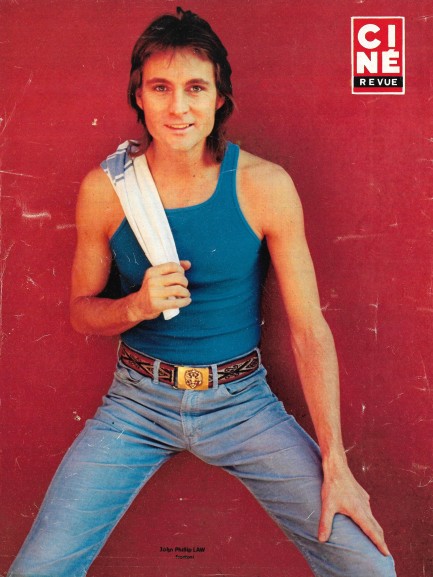

Remember the side trip to France we mentioned? Today you see the first of our acquired items, an issue of the cinema and television magazine Ciné-Revue, which was based in Belgium and published throughout Europe and the French speaking world. This one appeared today in 1975, and who is that on the cover other than Margaret Markov, a favorite star of bad U.S. exploitation movies of the era? We've seen her hanging out in the woods before. Remember this shot? The cover and centerfold of today's magazine, like that previous image, were made by Italian lensman Angelo Frontoni, who photographed scores of international actresses during the ’60s and ’70s. You've seen his work often on our website: check here, here, and especially here. He does a bang-up job with Markov, bringing to mind mythical gardens and similar fertile places. Inside the magazine are celebs such as Valerie Perrine, Anne Libert, Clark Gable, Carole Lombard, Marion Davies in a tinted shot, and on the rear cover John Phillip Law shows that he dresses to the left. That one's mostly for the Pulp Intl. girlfriends, but everyone should have a scroll and enjoy.

Mogambo features the cruelest beast in all of Africa—and its name is Clark Gable.

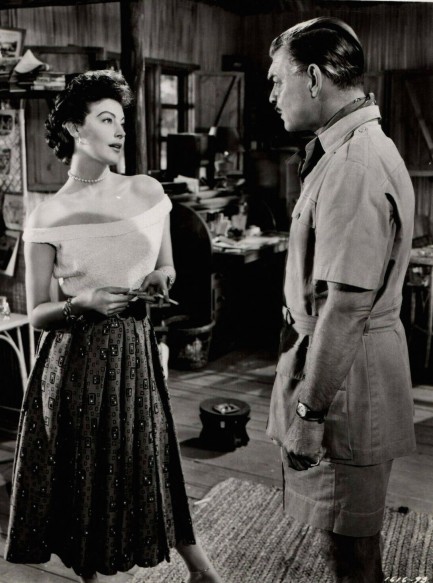

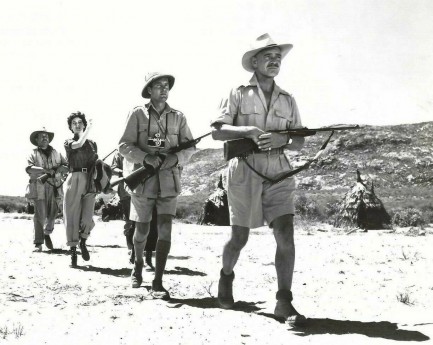

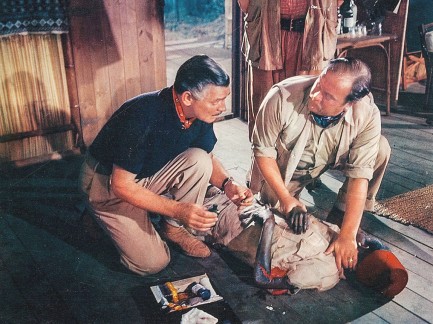

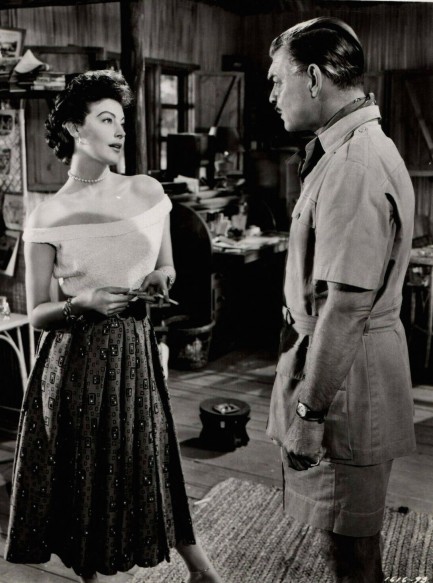

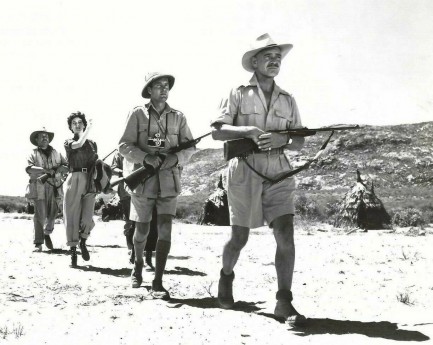

As famous as Mogambo is, we'd never seen it, had never read a review of it, and had no idea going in what it was about except that it was a safari movie and a remake of the 1932 adventure Red Dust, which we'd also never seen. There are few hit movies—especially with stars the stature of Clark Gable, Ava Gardner, and Grace Kelly—that we don't know at least a little something about. So we cleared the slate, cooked up some popcorn in our special Lindy's hand-cranked popper, and settled in for a screening.

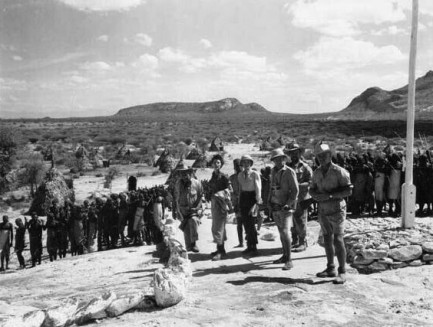

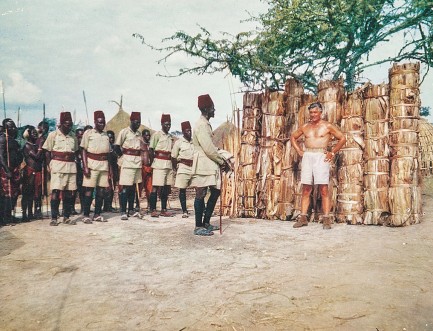

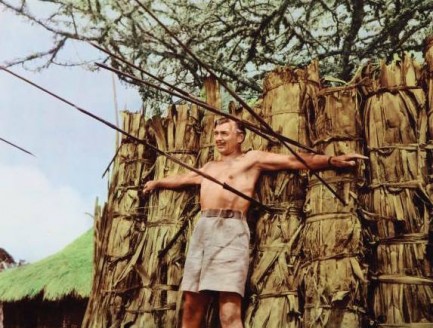

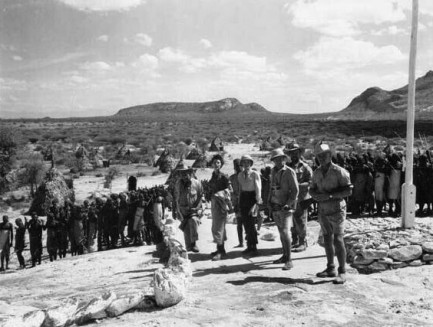

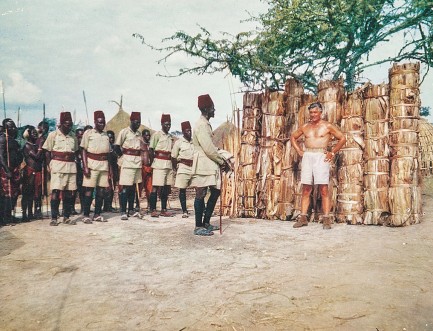

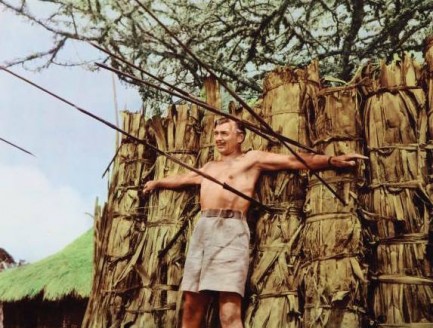

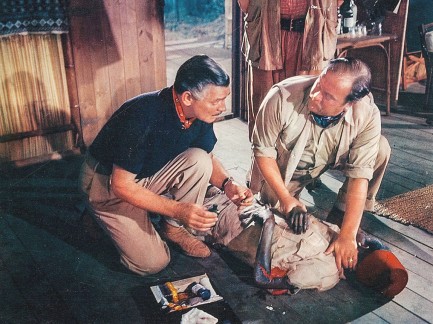

Shot in Kenya, Uganda, French Equatorial Africa (now Central African Republic), and the Tanganyika region of what is now Democratic Republic of Congo, the movie is about a hard-edged safari guide and hunter played by Gable (also the star of Red Dust, by the way) who tries to score with both Gardner and Kelly, and soon has them at each other's throats. These old movies often work on the presumption that the male star is irresistible—period. As a result, screenwriters were sometimes lazy. They'd fail to write the male lead with any charm at all.

That holds true here, as Gable is gruff, rude, twenty years older than Gardner, and almost thirty years older than Kelly. We're fine about the age difference, unlike the “age appropriate” crowd that thinks women are capable of making any decision except ones about whom they love, but because Grant is a complete sourdough some charm would have made Gardner's and Kelly's attraction to him more understandable. Handsome though he may be, here he's nothing more than moustache, hair tonic, and bossiness. But okay, Gardner and Kelly are both in states of need, and Gable is more than happy to introduce them to his bush snake, so what you get is a love triangle folded inside a Technicolor safari adventure. Fine.

The production is spiced up with majestic scenery, nice costumes, realistic animal footage, an overwhelming feel of the exotic, the tantalizing implication of intimacy with two of the most beautiful women in cinema, and a deft, assured performance from Gardner. In fact, while Gable is top billed, Ava gets nearly all the good lines. “Listen, buster,” she scolds Clark, “you and your quick-change acts aren't gonna hang orange blossoms all over me just because you feel the cold weather coming on!” That's a scathing way to call someone old and desperate. But Gable has his moments too. We liked when he blustered, “You know how it is on safari. It's in all the books. The woman always falls for the white hunter and we guys make the most of it.” That's meta, so we hear.

Obviously, tribespeople figure prominently, and you can discern marginal improvement in their portrayal since the days of Weissmuller's Tarzan. They're still just ornamentation in their own lands, but at least none lay down their lives to save a white man who's spent most of his screen time cracking a whip at them. Whew. Overall, we thought Mogambo was decent. Not great, mind you—because Gable deserved to play a more nuanced character and did not have that chance—but it was decent. It premiered today in 1953.

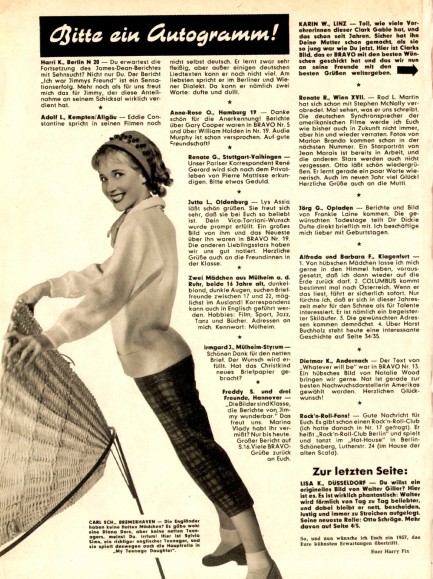

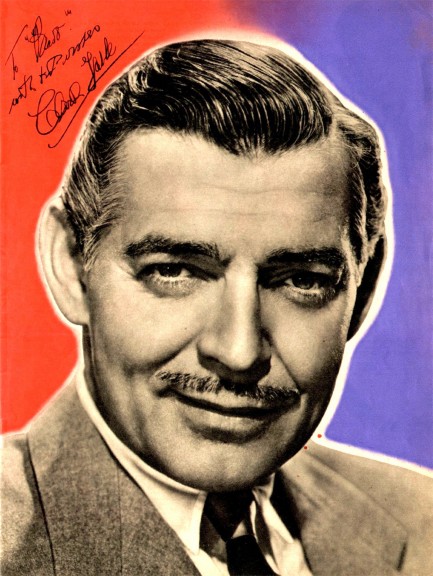

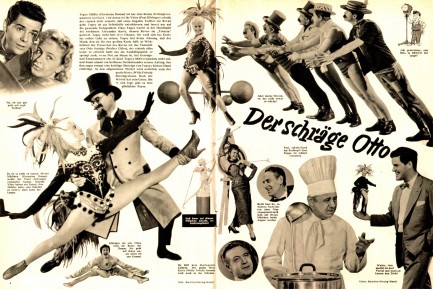

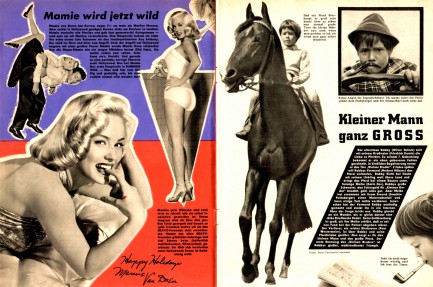

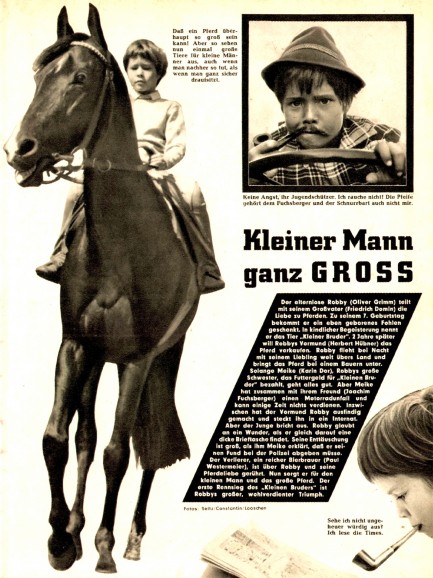

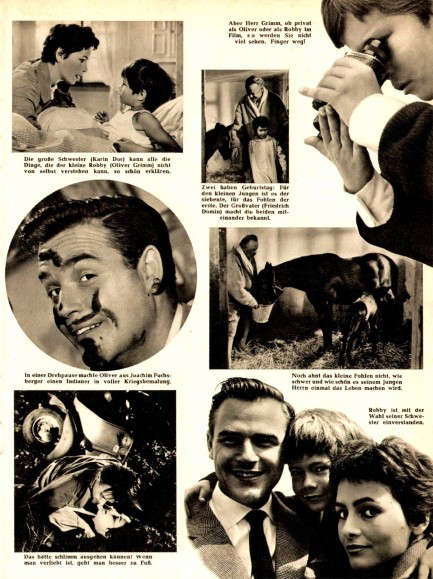

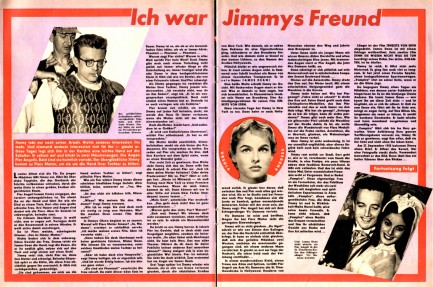

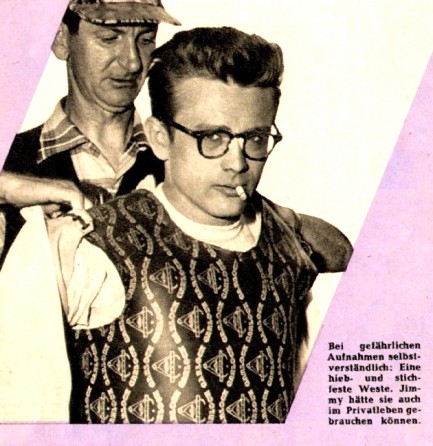

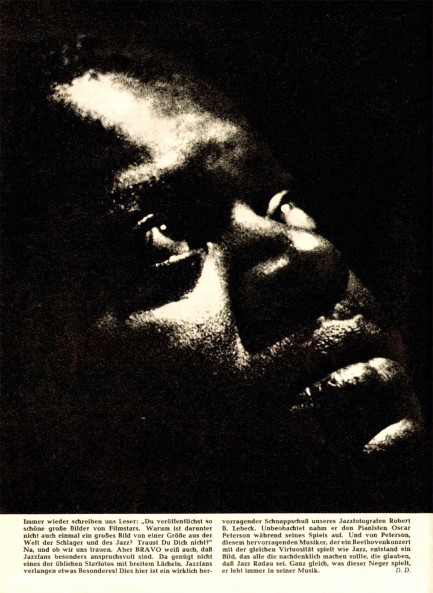

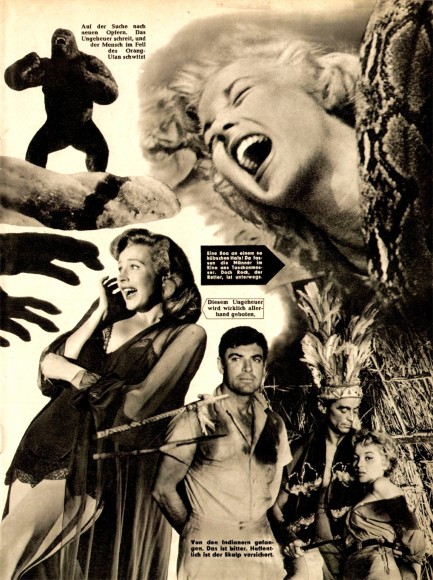

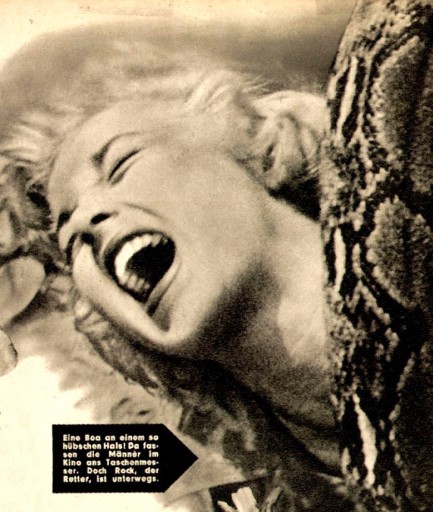

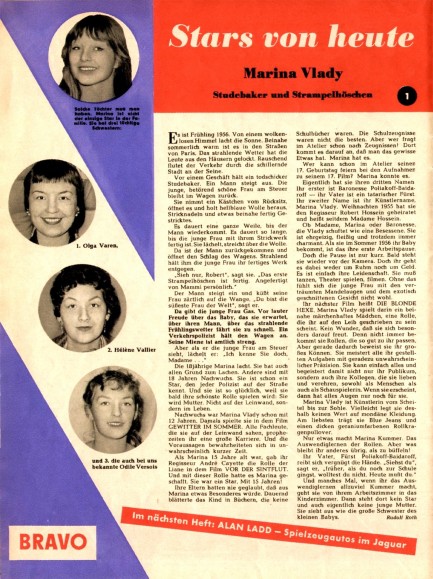

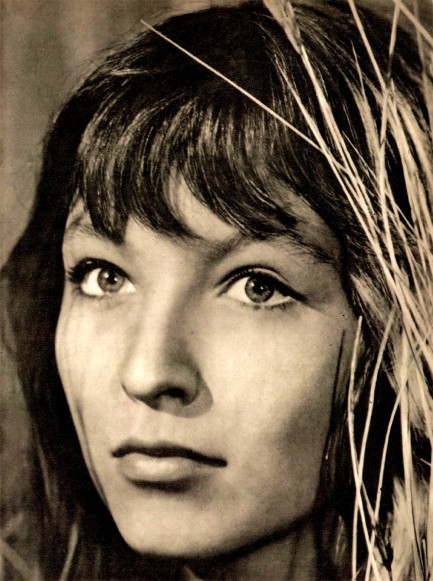

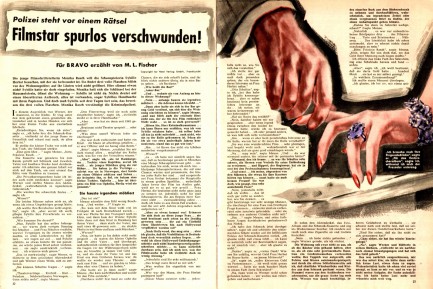

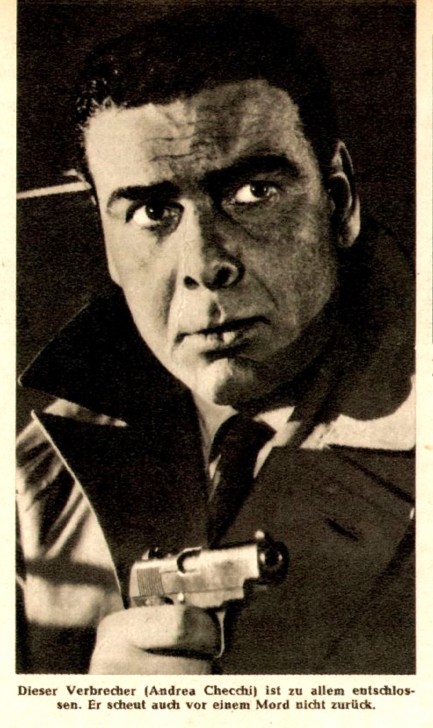

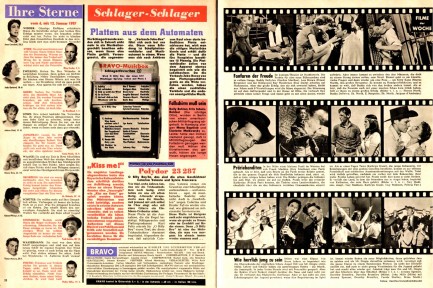

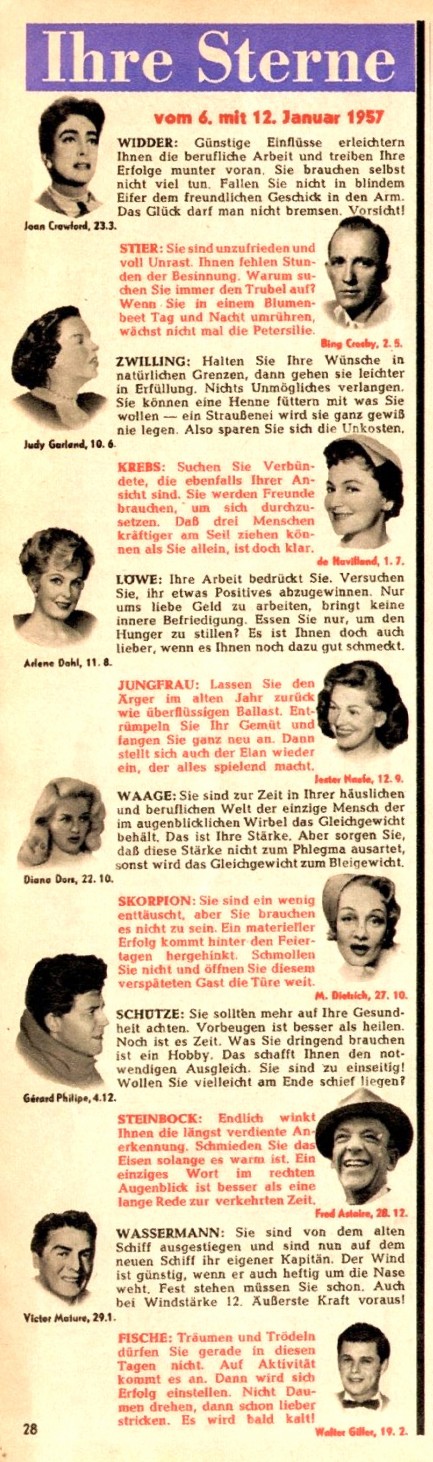

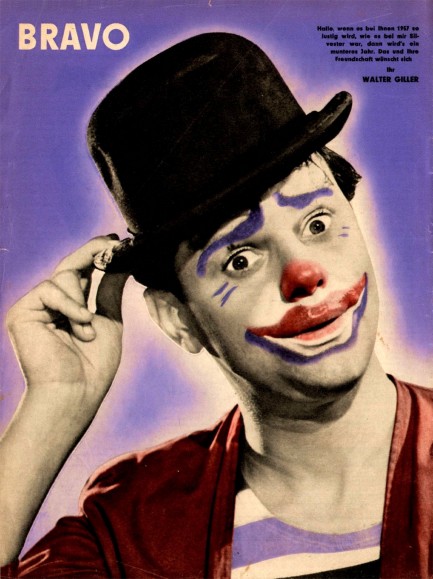

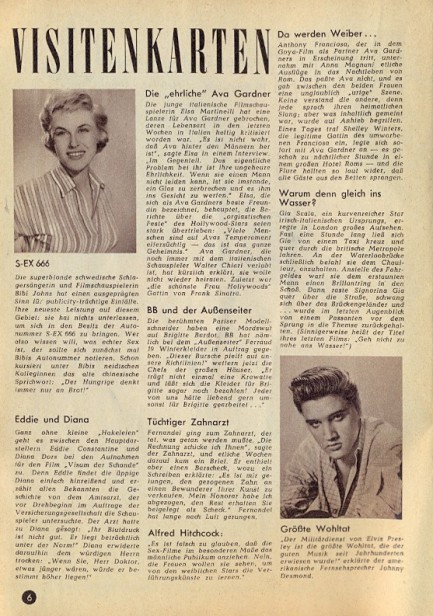

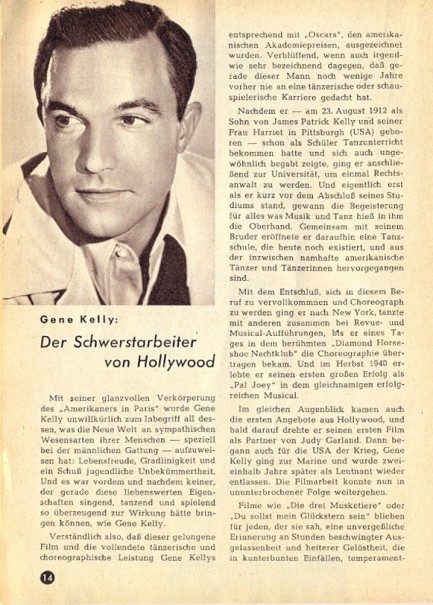

West German magazine tears down the wall.

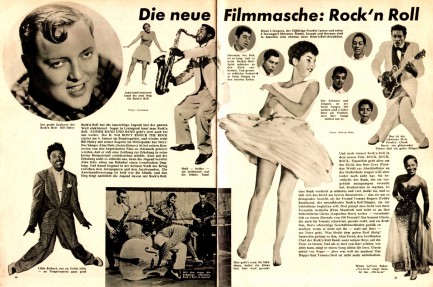

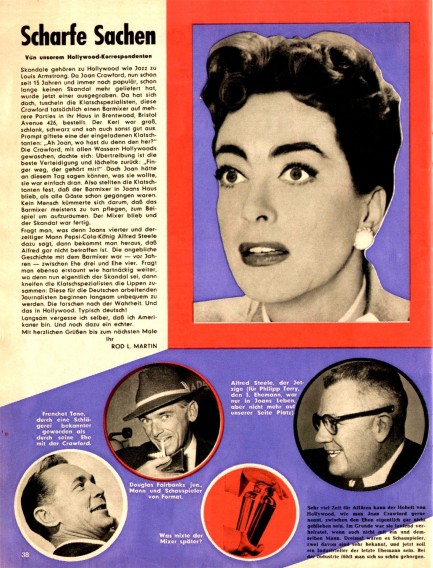

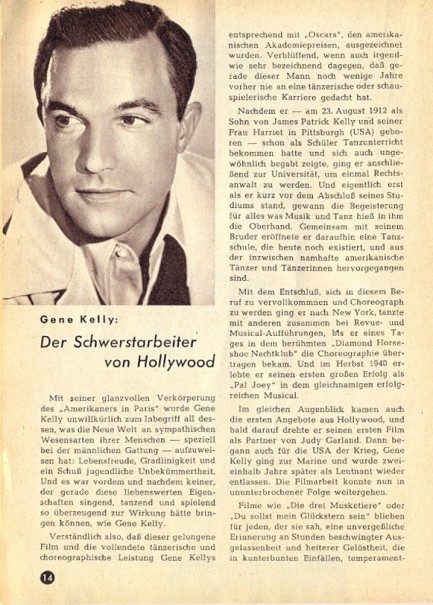

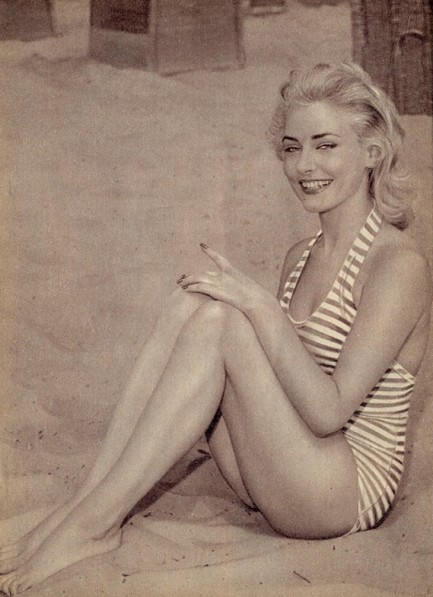

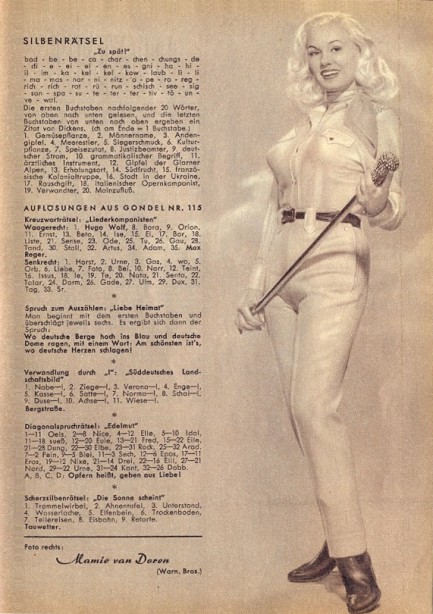

German isn't one of our languages, but who needs to read it when you have a magazine with a red and purple motif that's pure eye candy? Every page of this issue of the pop culture magazine Bravo says yum. It hit newsstands today in 1957 and is filled with interesting and rare starfotos of celebs like Romy Schneider, Horst Buchholz, Clark Gable, Karin Dor, Mamie Van Doren, Ursula Andress, Marina Vlady, Corinne Calvet, jazzists Oscar Peterson and Duke Ellington, and many others. This was an excellent find.

We perused other issues of Bravo and it seemed to us—more so in those examples than this one—that it was a gay interest publication. After a scan around some German sites for confirmation we found that it was as we thought. The magazine's gay themes were subtle, but they were there, and at one blog the writer said that surviving as a gay youth in West Berlin during the 1960s, for him, would have been impossible without Bravo. We will have more from this barrier smashing publication later. Thirty-five panels below.

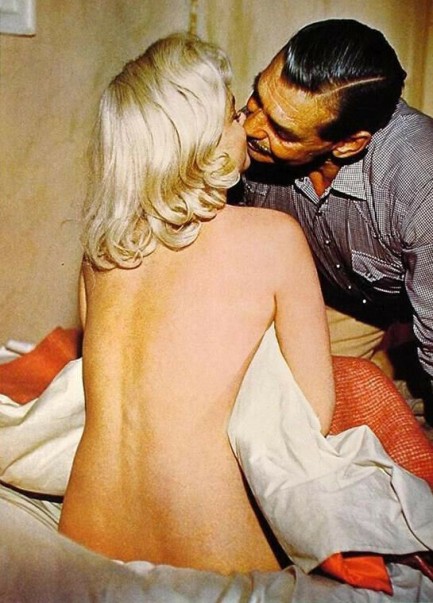

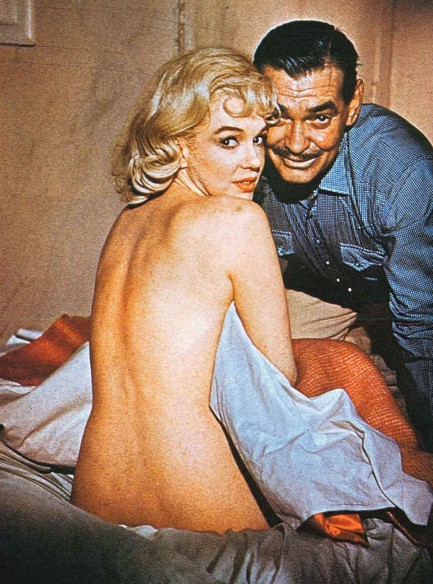

You're not as clever as you think, Clark. I realized you were muffing your lines on purpose way back on take forty.

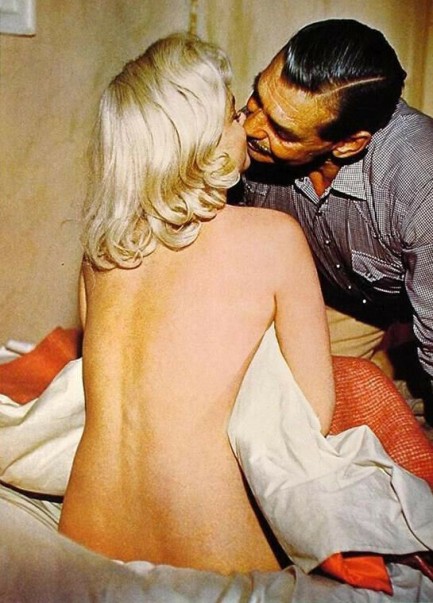

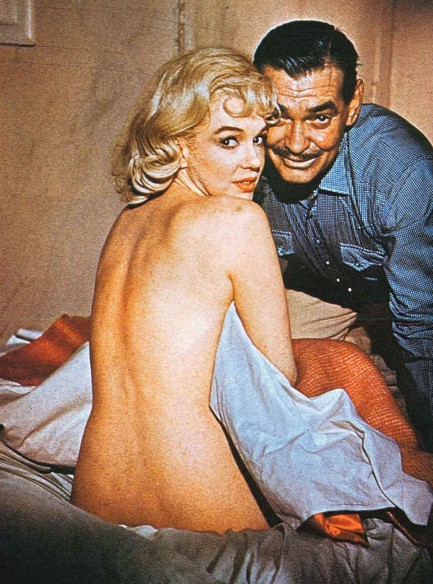

Who's that mystery woman kissing Clark Gable? Why it's Marilyn Monroe. Not really a mystery though, as she's instantly recognizable from any angle. There's almost no such thing as a new Monroe photo, but there are some you don't see often. This one and the one below fall into that category. They were made when she was filming The Misfits, which premiered today in 1961. The scene that provided these shots also featured a Monroe nude flash when she gets out of bed to dress. Director John Huston cut those frames, and they were thought lost, but were rediscovered (though not made public) in 2018.

This was Gable's last movie. He had a heart attack in November 1960, possibly in the middle of this kissing scene, and didn't survive. Just kidding. He had his heart attack two days after filming wrapped. But we bet he was thinking about Monroe when it happened. This was also her last movie. She was filming Something Got To Give in 1962 but died of an overdose before finishing it. The Misfits was a box office disappointment when released, but was considered to be Gable's best film performance, and one of Monroe's best, as well. We don't fully agree, but you might. It's certainly worth a viewing.

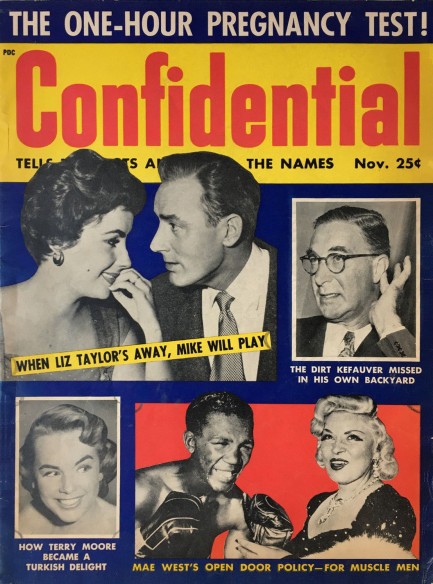

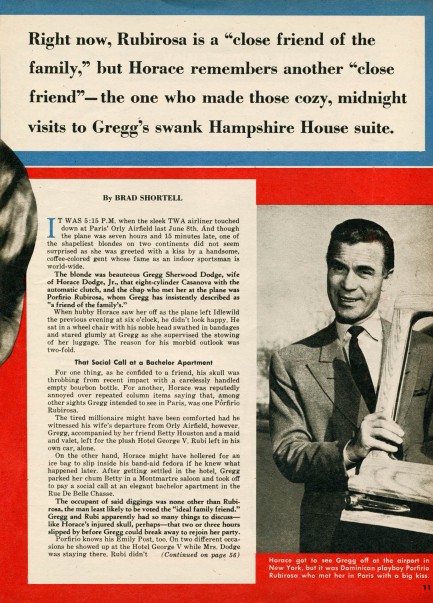

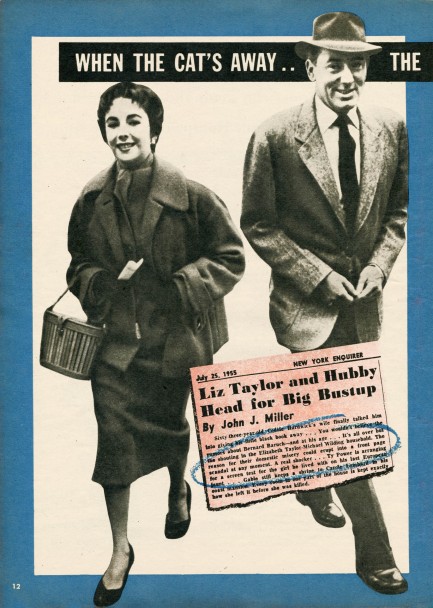

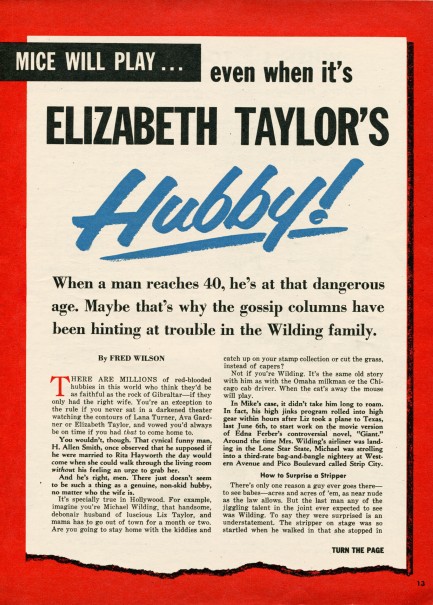

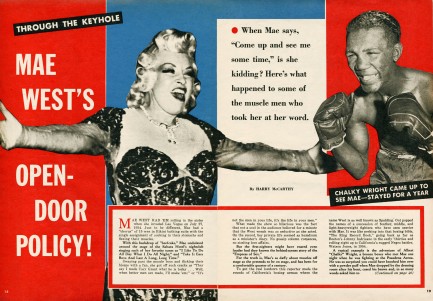

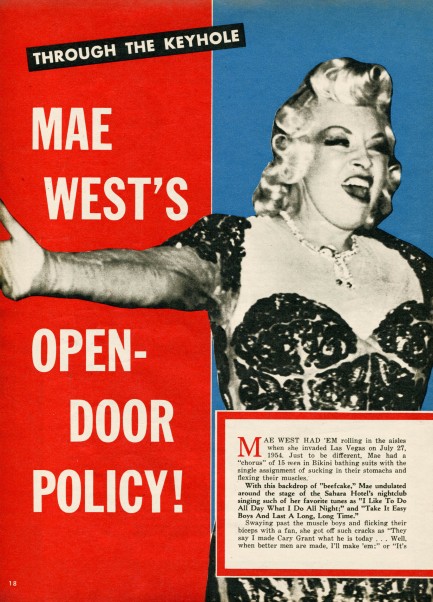

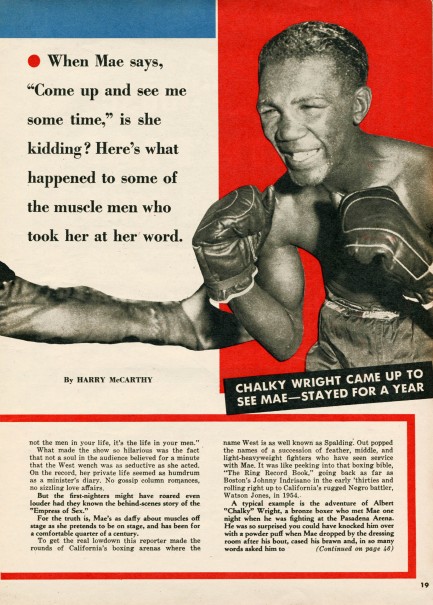

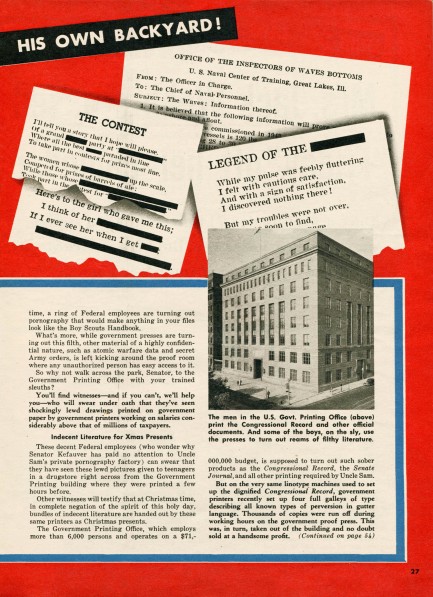

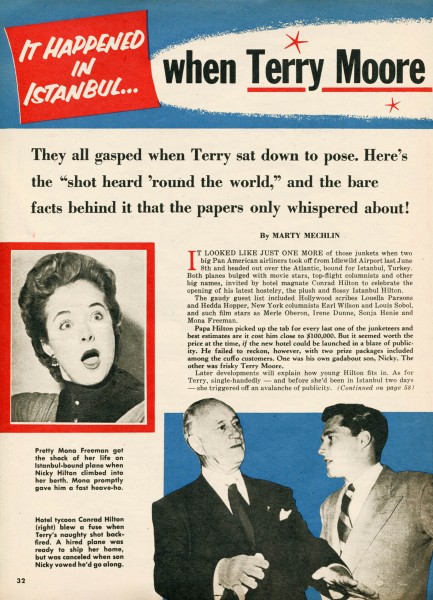

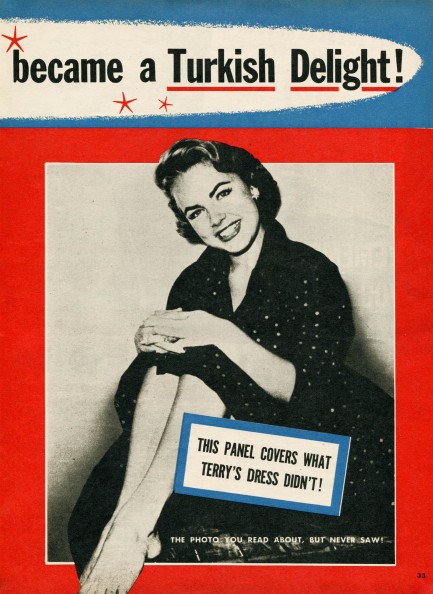

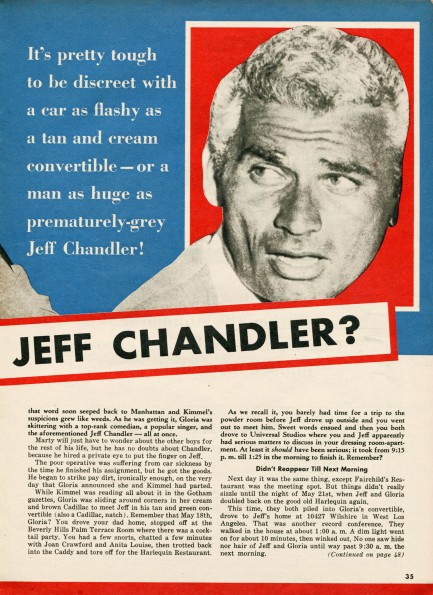

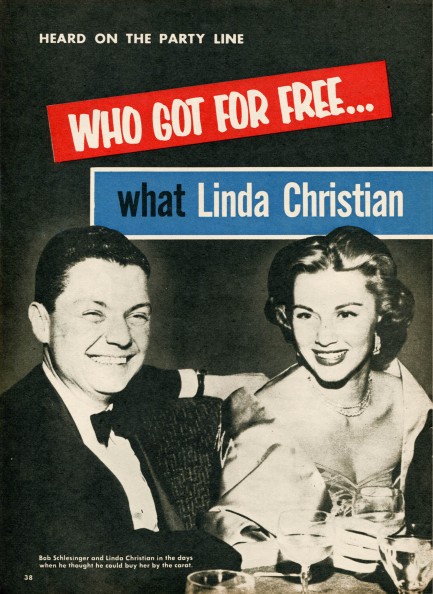

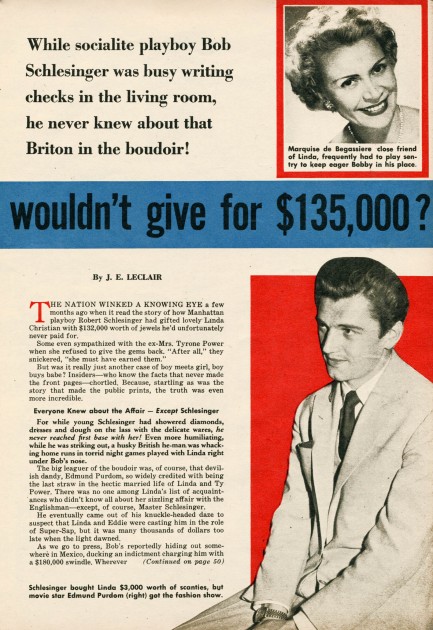

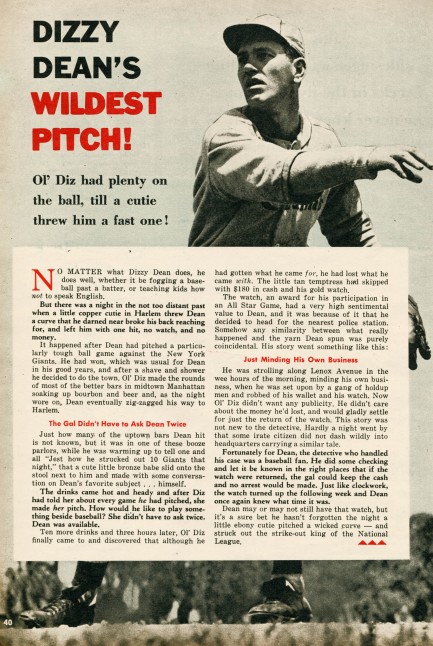

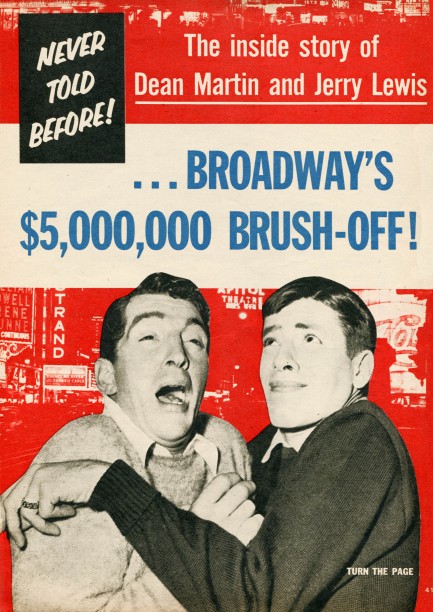

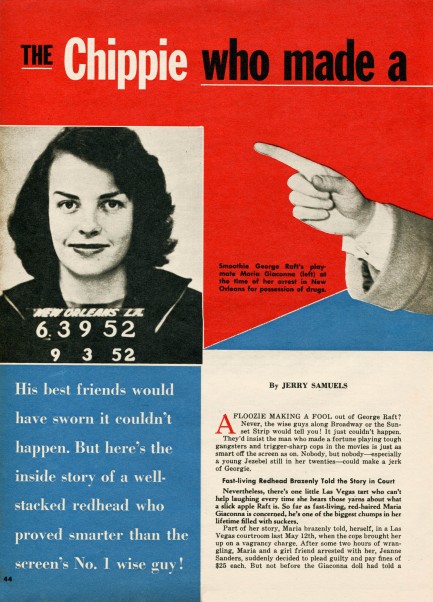

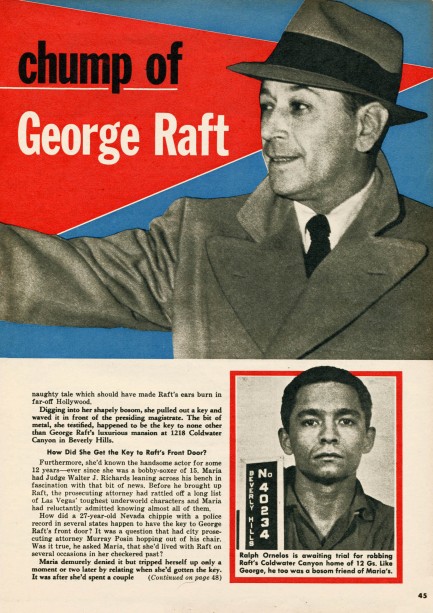

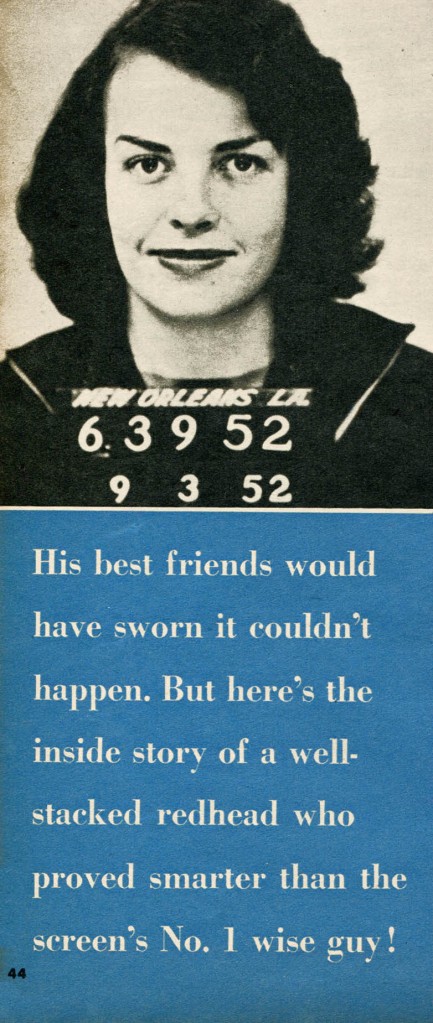

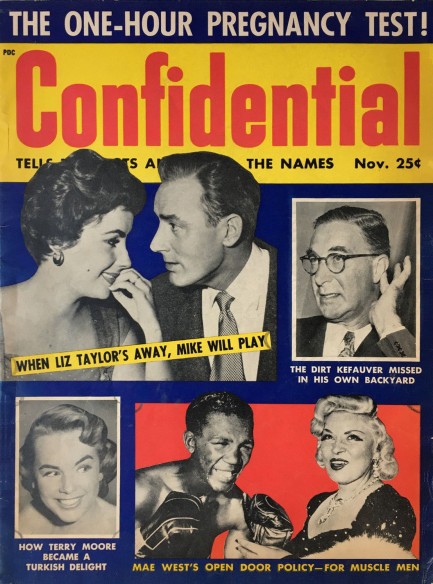

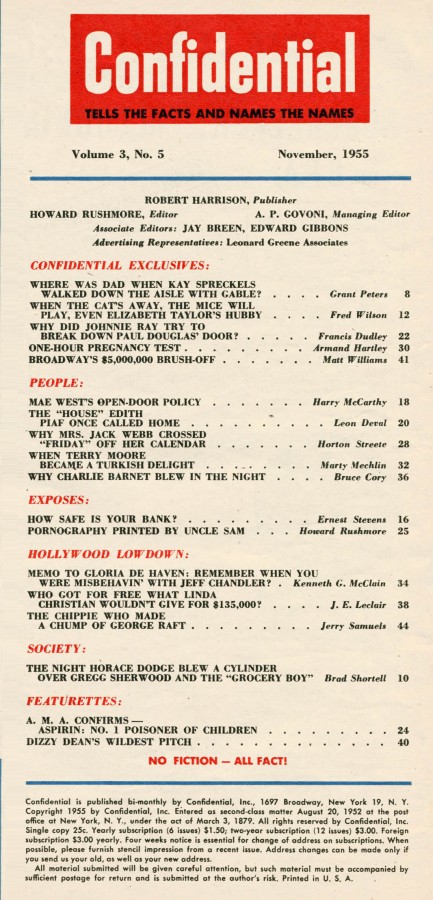

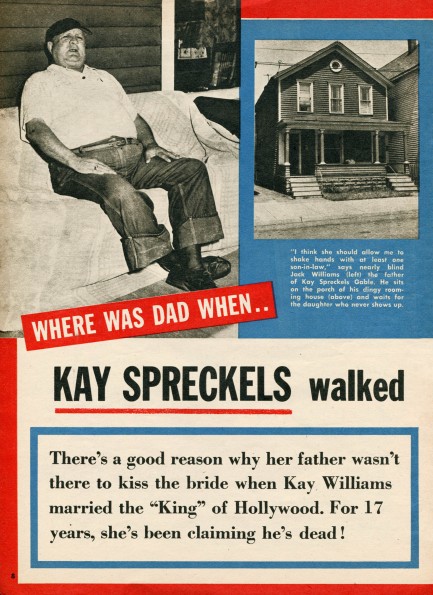

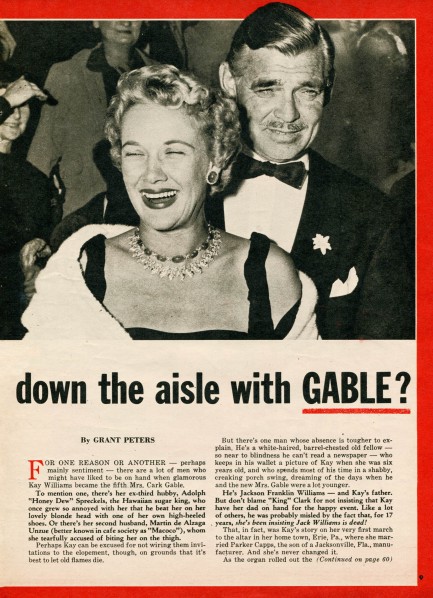

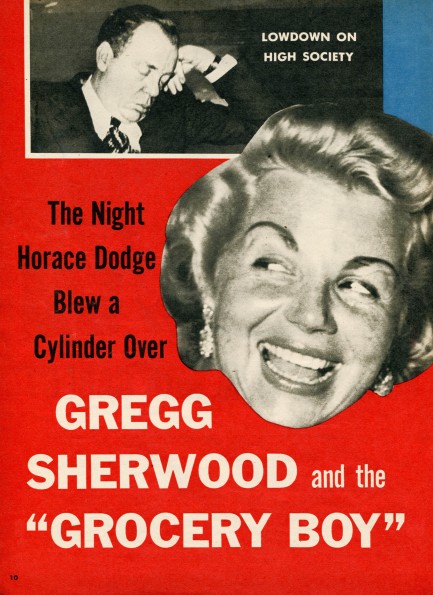

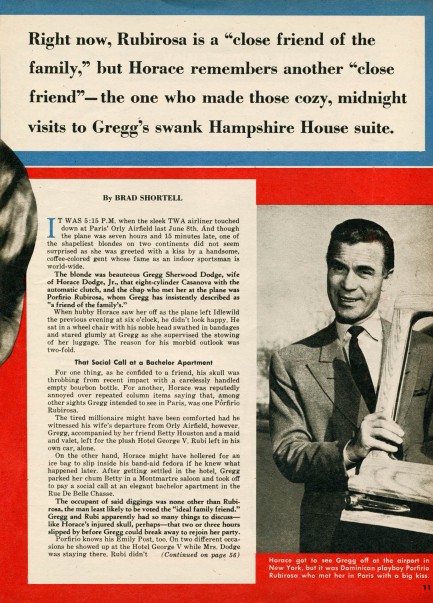

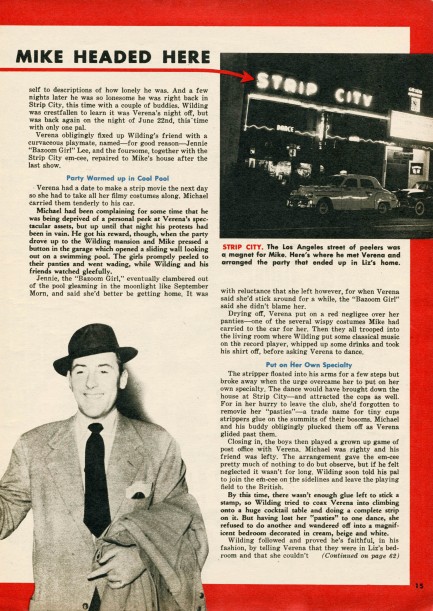

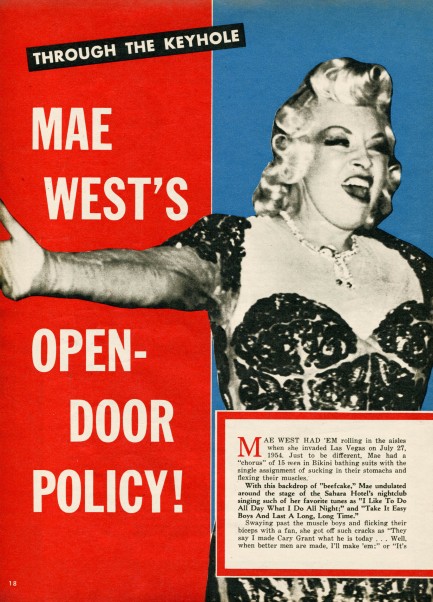

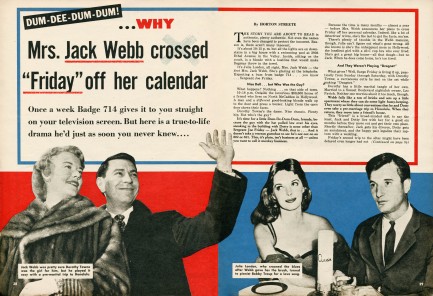

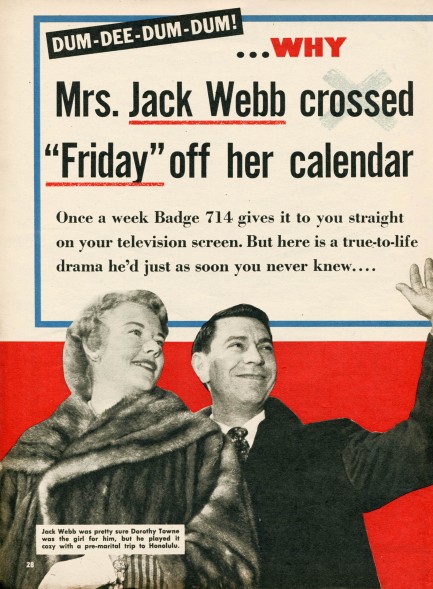

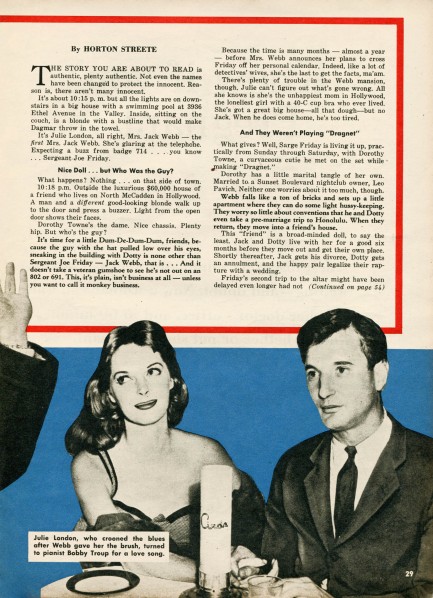

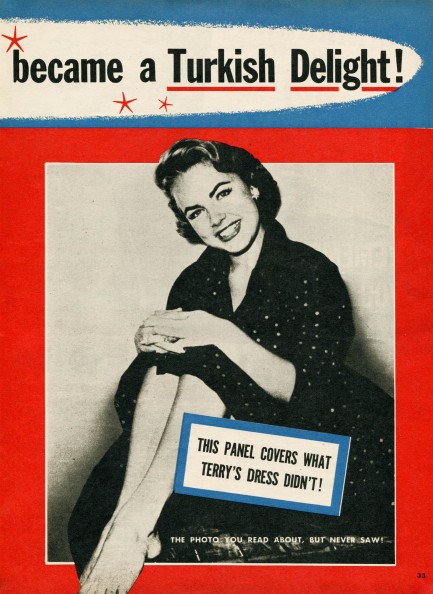

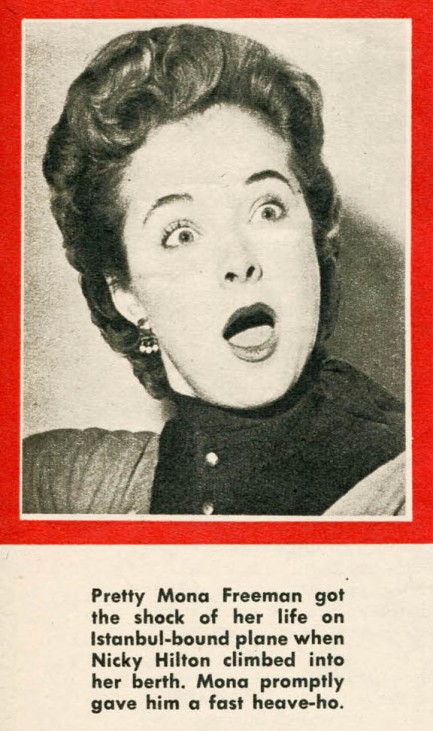

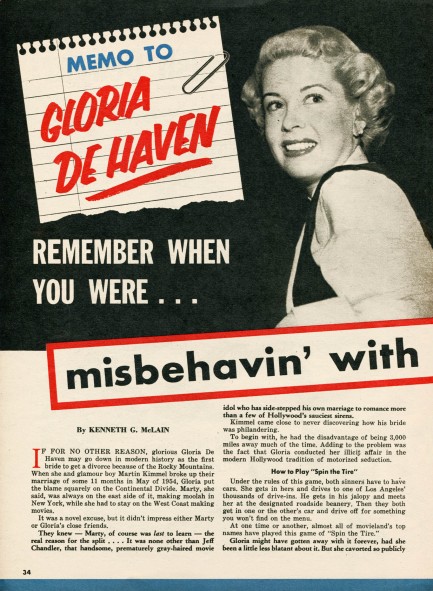

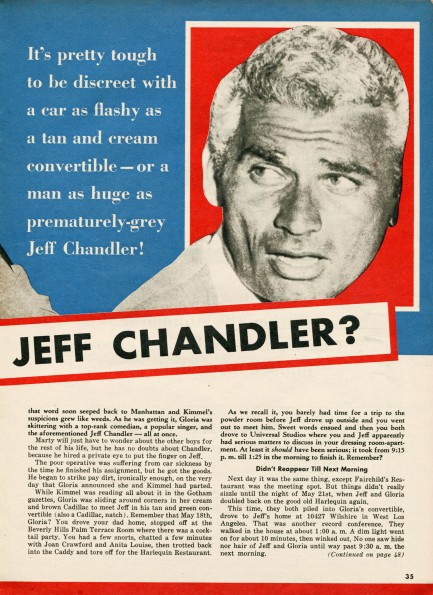

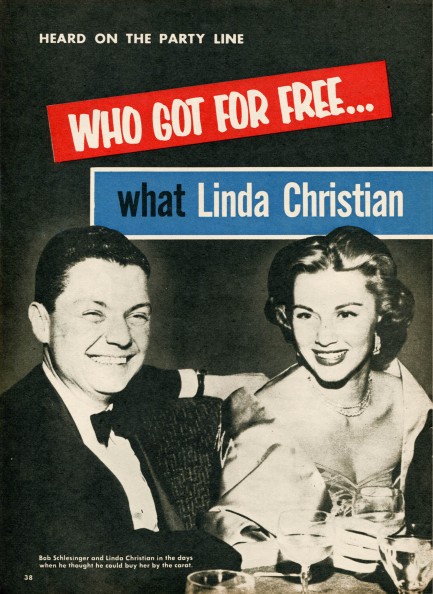

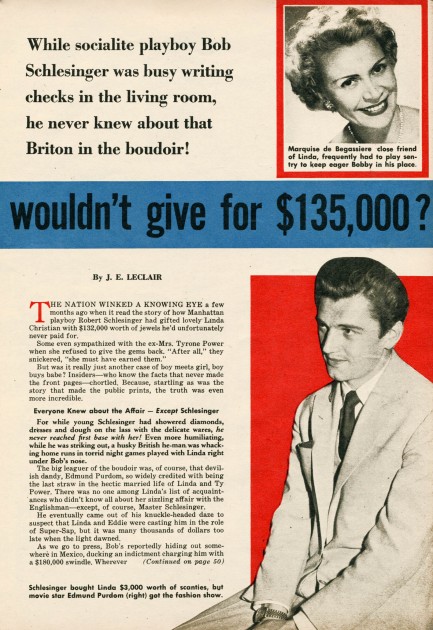

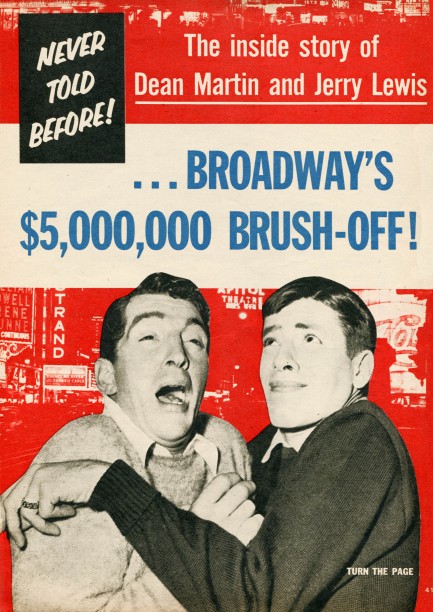

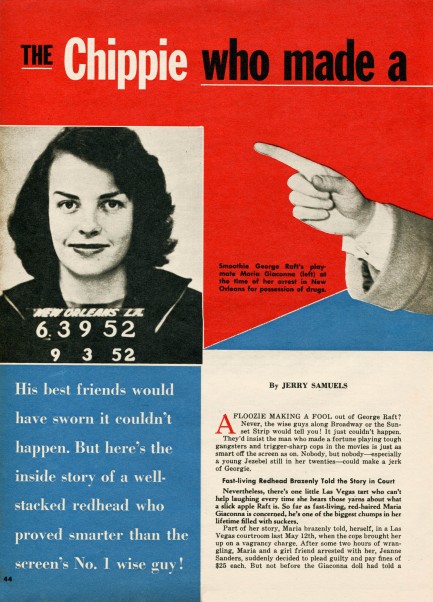

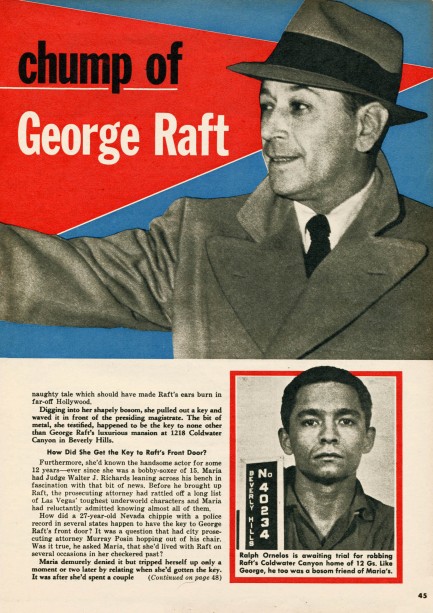

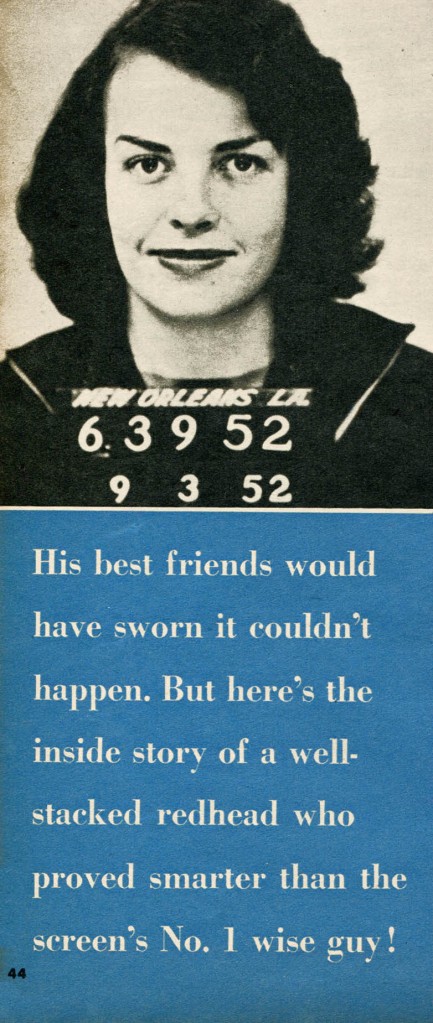

Confidential sinks its teeth into the juiciest celebrity secrets.

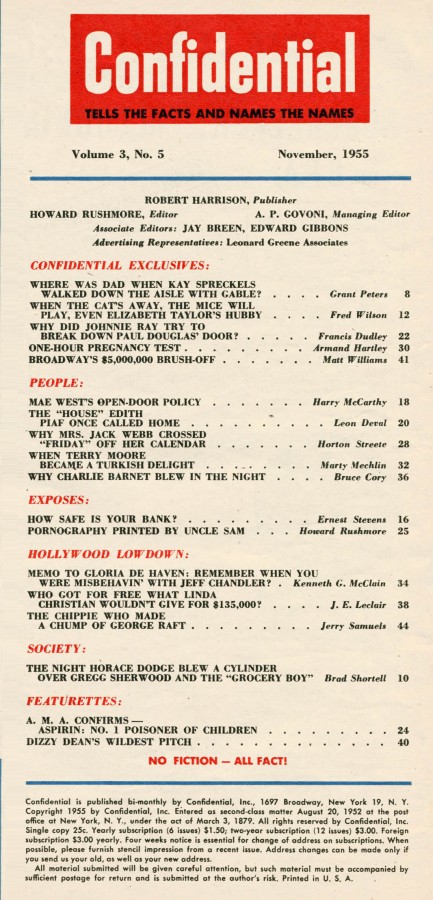

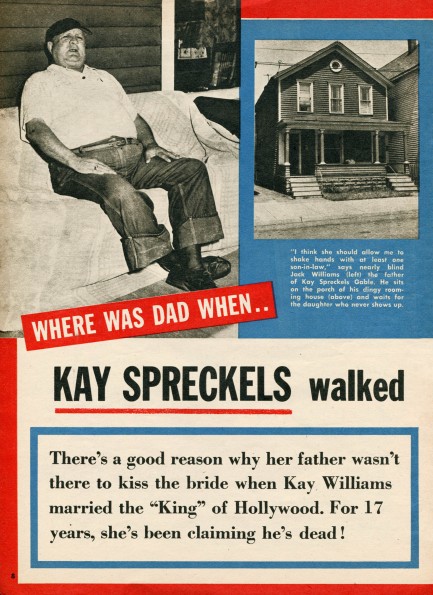

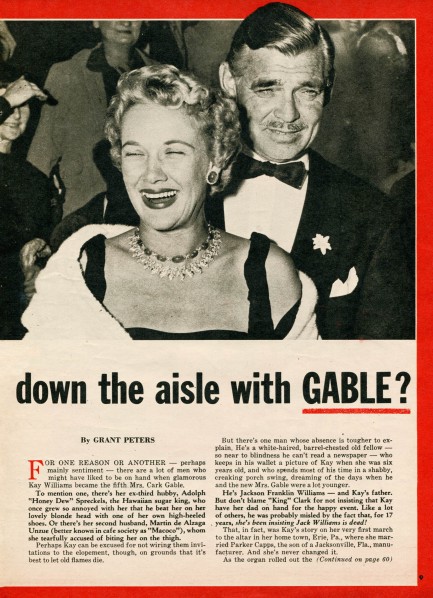

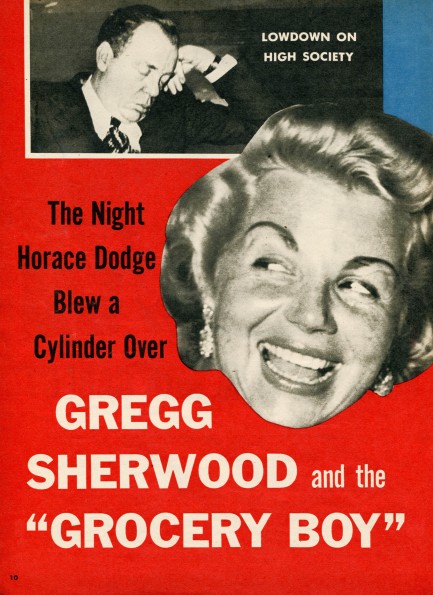

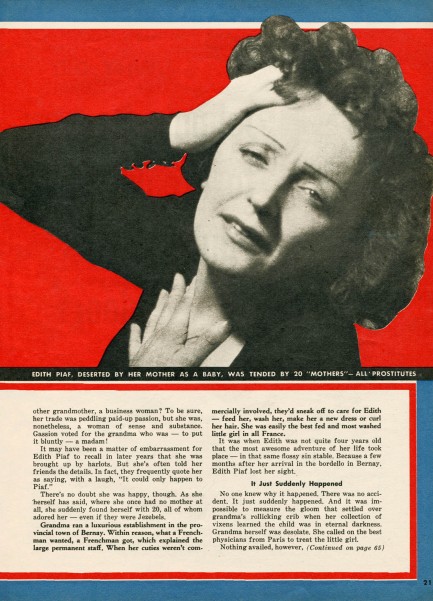

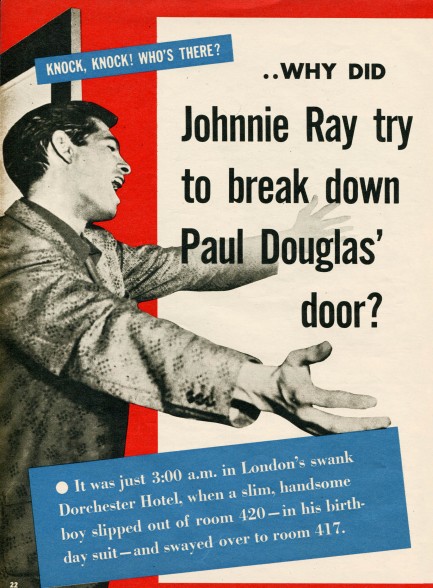

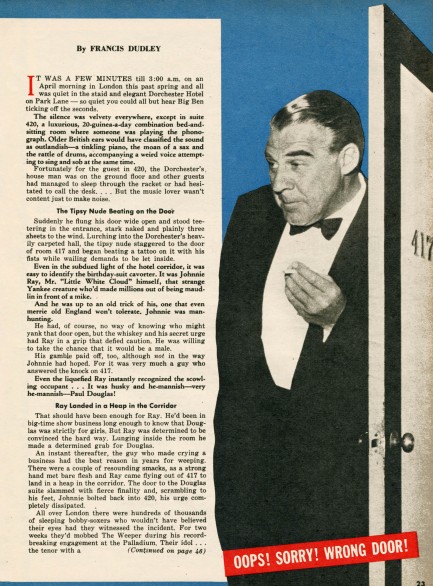

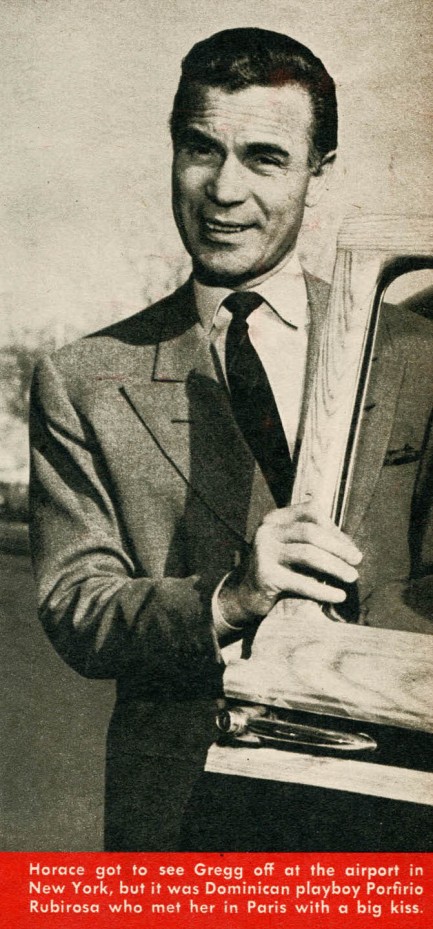

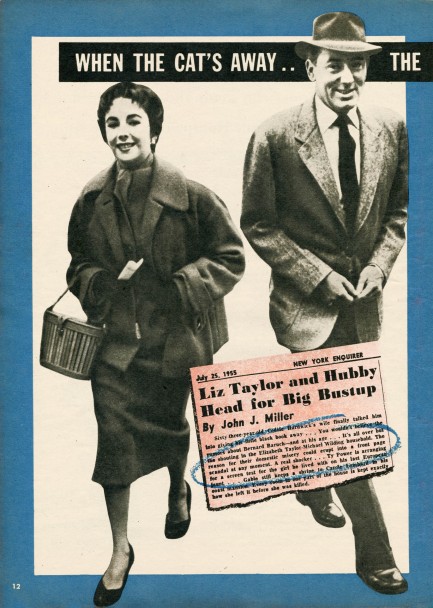

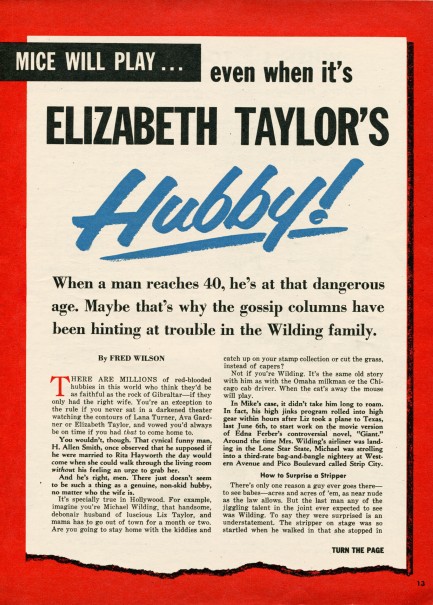

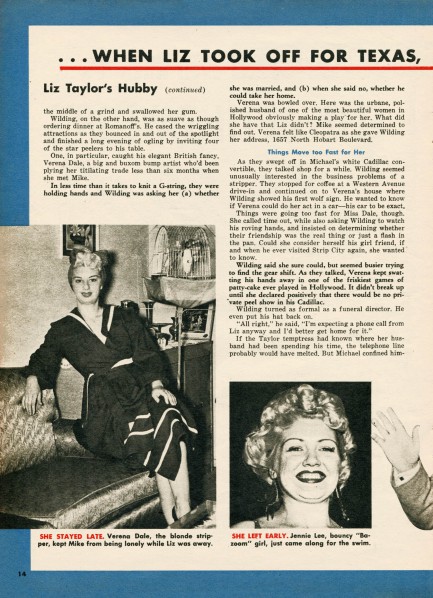

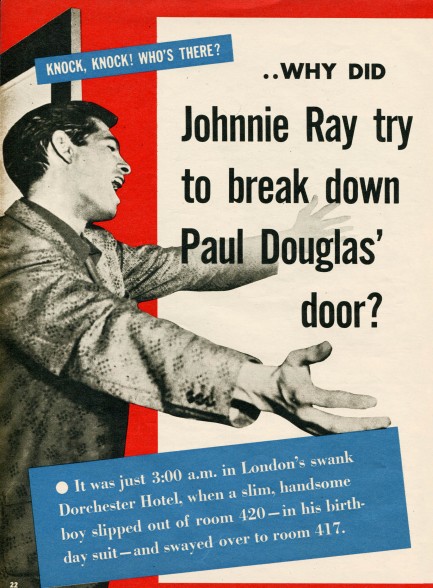

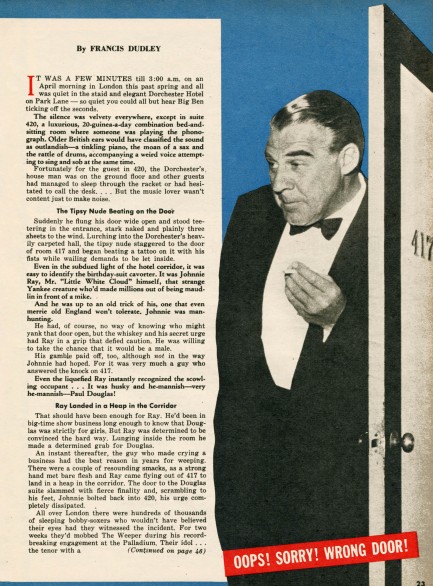

Confidential magazine had two distinct periods in its life—the fanged version and the de-fanged version, with the tooth pulling done courtesy of a series of defamation lawsuits that made publisher Robert Harrison think twice about harassing celebrities. This example published this month in 1955 is all fangs. The magazine was printing five million copies of each issue and Harrison was like a vampire in a blood fever, hurting anyone who came within reach, using an extensive network spies from coast to coast and overseas to out celebs' most intimate secrets.

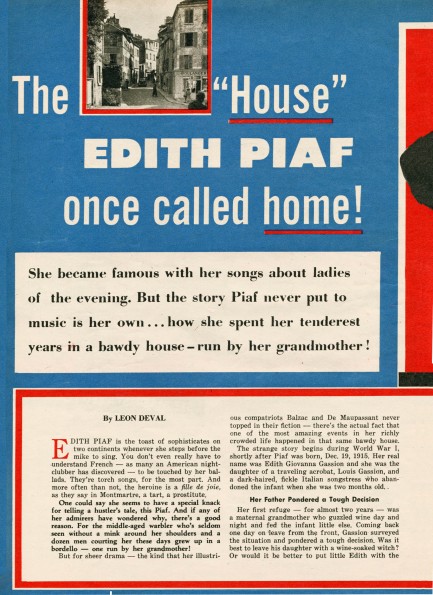

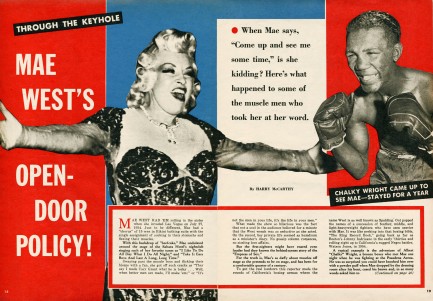

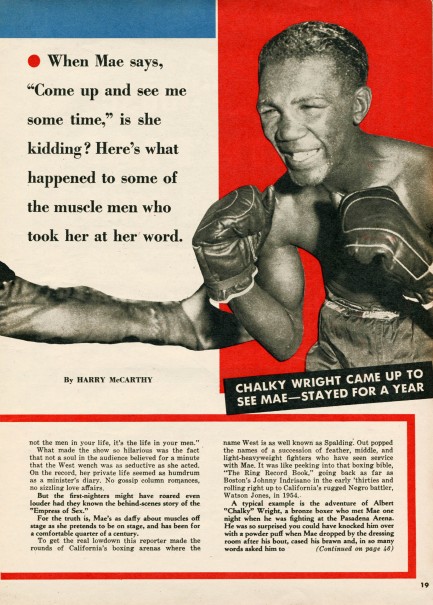

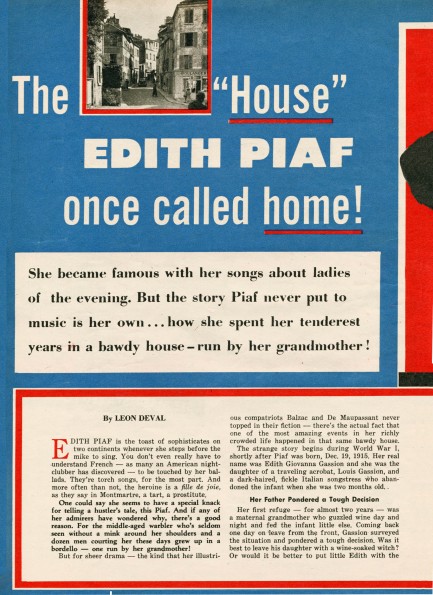

In this issue editors blatantly call singer Johnnie Ray a gay predator, spinning a tale about him drunkenly pounding on doors in a swanky London hotel looking for a man—any man—to satisfy his needs. The magazine also implies that Mae West hooked up with boxer Chalky White, who was nearly thirty years her junior—and black. It tells readers about Edith Piaf living during her youth in a brothel, a fact which is well known today but which wasn't back then.

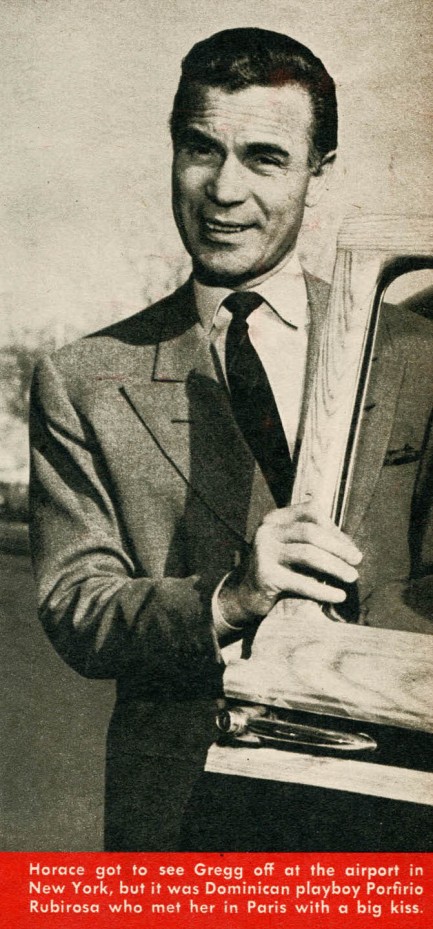

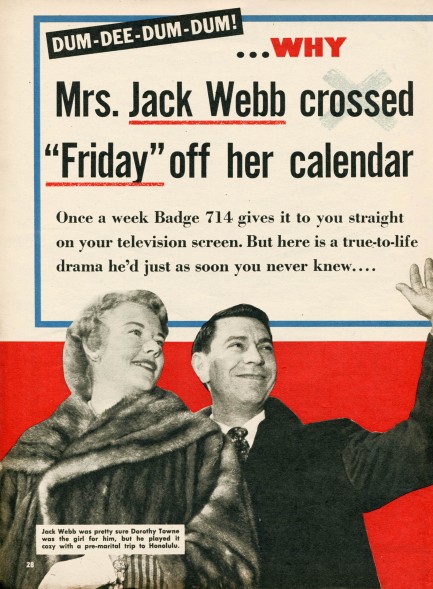

The list goes on—who was caught in whose bedroom, who shook down who for money, who ingested what substances, all splashed across Confidential's trademark blue and red pages. Other celebs who appear include Julie London, Jack Webb, Gregg Sherwood, and—of course—Elizabeth Taylor. Had we been around in 1955 we're sure we would have been on the side of privacy rights for these stars, but today we can read all this guilt-free because none of it can harm anyone anymore. Forty panels of images below, and lots more Confidential here.

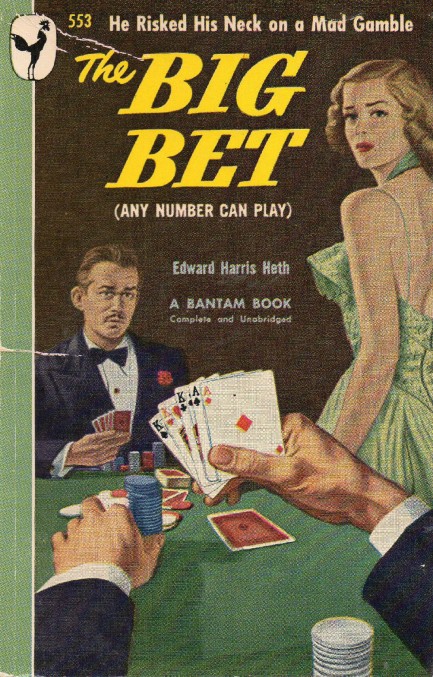

I'll see your ten thousand and raise you my wife. Sorry, babe.

The Big Bet tells the story of a professional gambler and owner of a gaming parlor who faces three obstacles—his health is poor, his son is ashamed of him, and his wife is unhappy. Retirement and a move to Florida seem to be the answer to all three problems. Over the course of one night the protagonist Charley King sees two lucky gamblers whittle away his fortune in a card game, learns that a police raid and jail is imminent, and is served a legal summons. In mounting desperation he must win his fortune back and deal with the other problems—and quickly—if he has any hope of escaping to a better life. If that sounds compelling we can tell you it is. The book, which appeared in 1945 under the title Any Number Can Play, was made into a stage production, and subsequently into a 1949 film starring Clark Gable and Alexis Smith. The cover art on this 1948 Bantam edition was painted by Robert Doares.

How'd ya like to teach an old dog some new tricks?

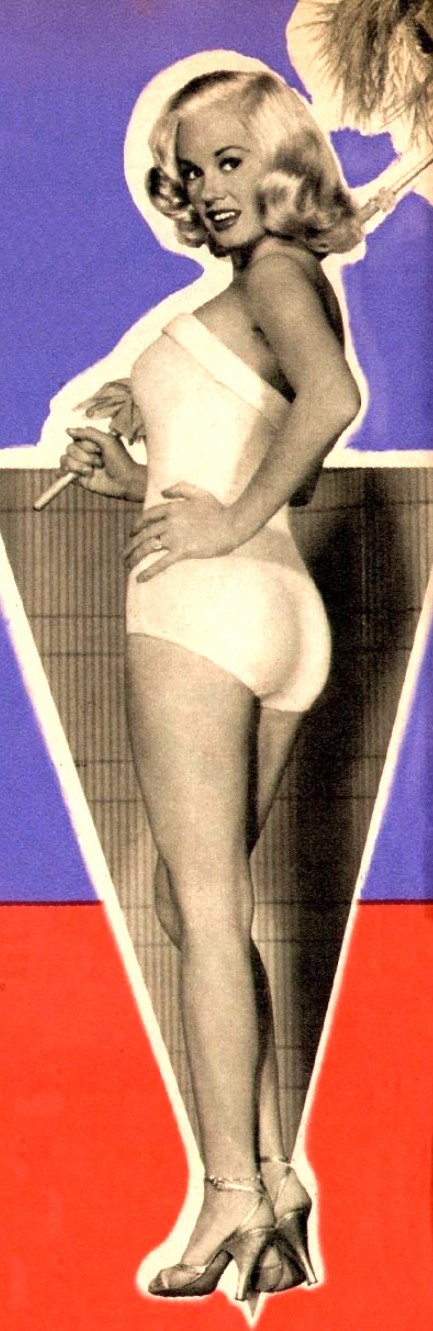

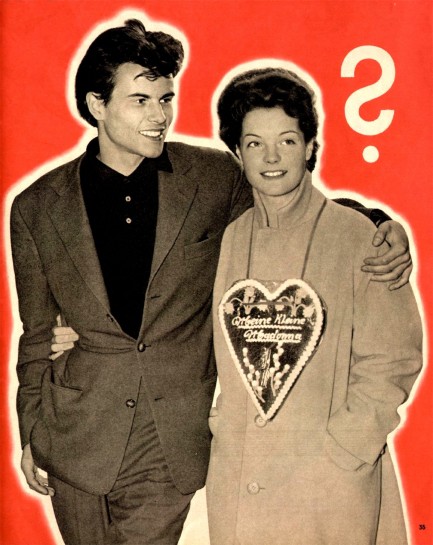

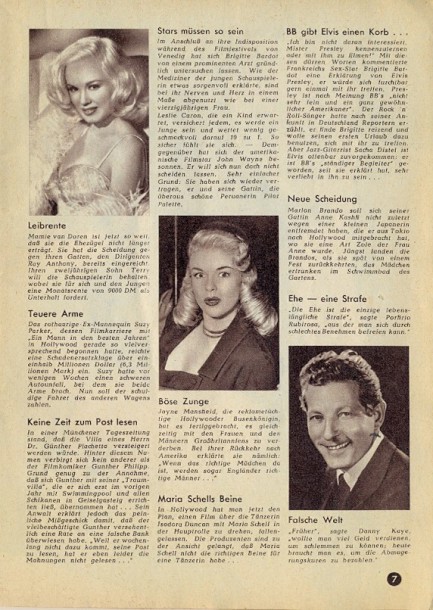

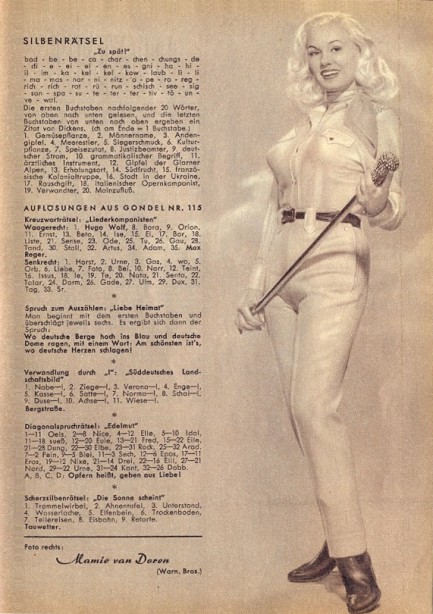

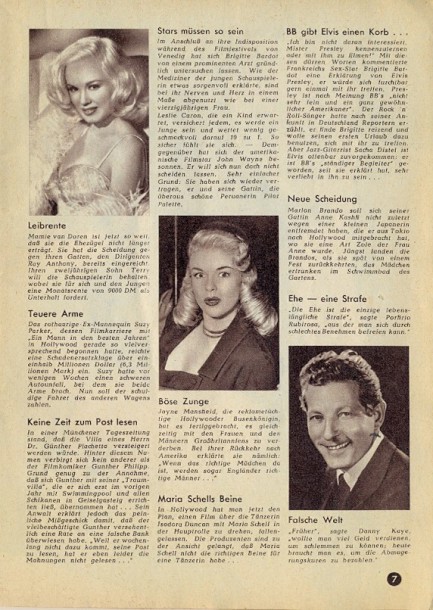

Clark Gable poses for a candid photo with Mamie Van Doren, his co-star in the 1958 Paramount romantic comedy Teacher's Pet. Van Doren wasn't Gable's love interest in the film—that was Doris Day. And Day wasn't the pet—that was Gable. The story deals with a grizzled veteran reporter ordered by his editor to help a college professor with her journalism class, and how his initial reluctance turns to attraction. Looks like he was plenty attracted to Van Doren too, though, doesn't it? And really, who could blame him? The photo was made just as production on Teacher's Pet began. That was today in 1957.

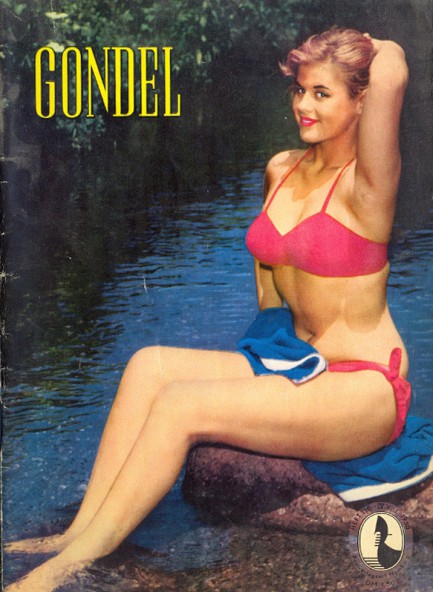

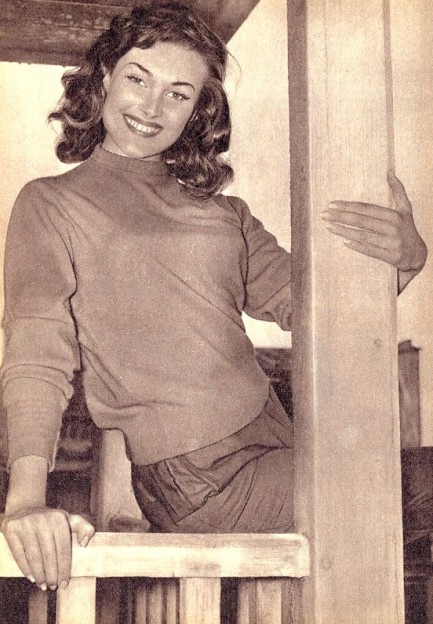

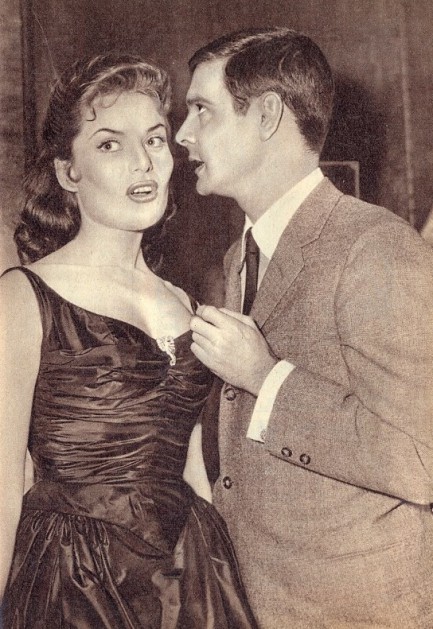

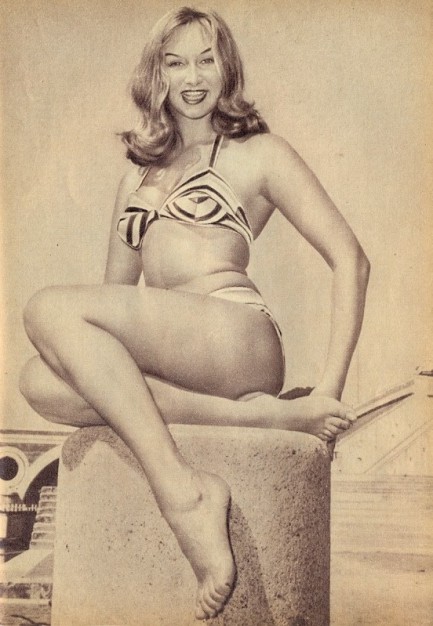

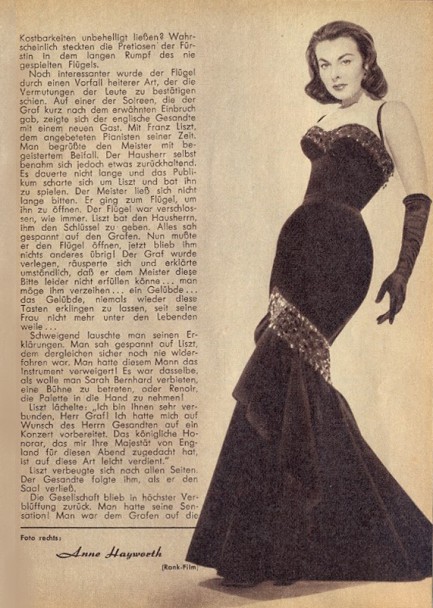

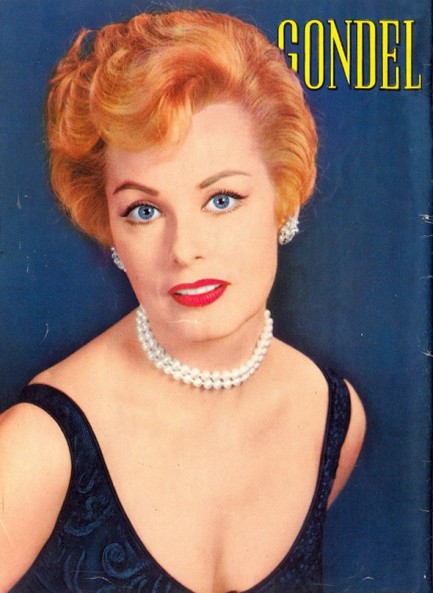

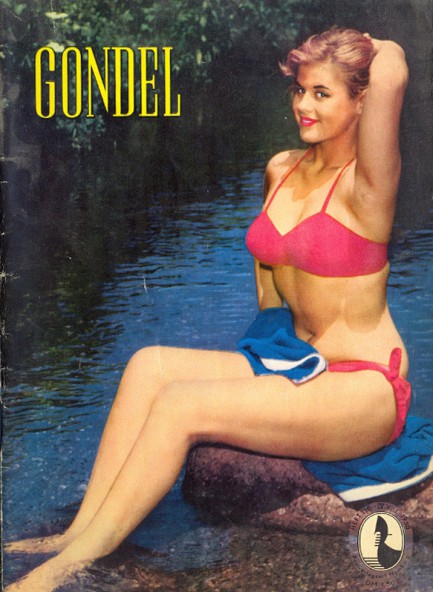

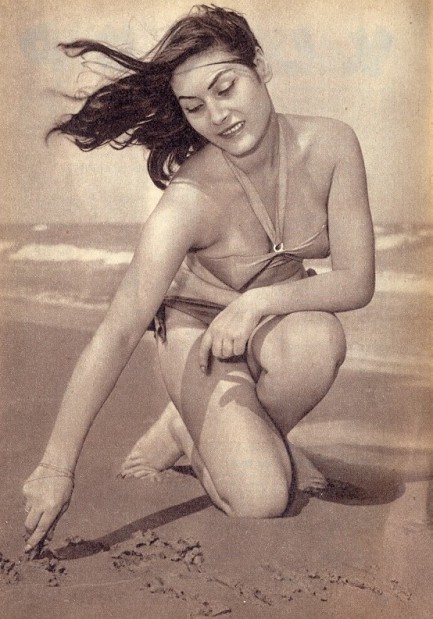

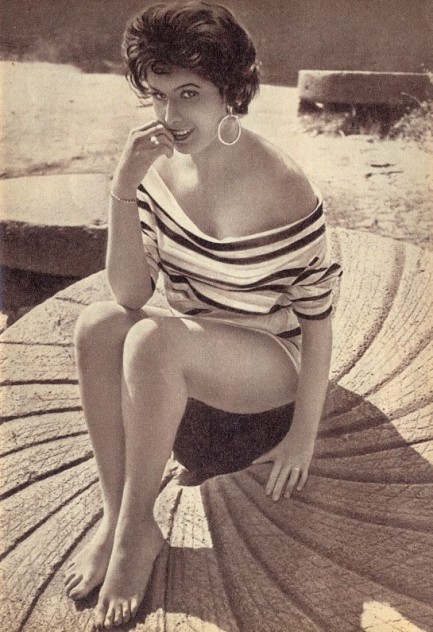

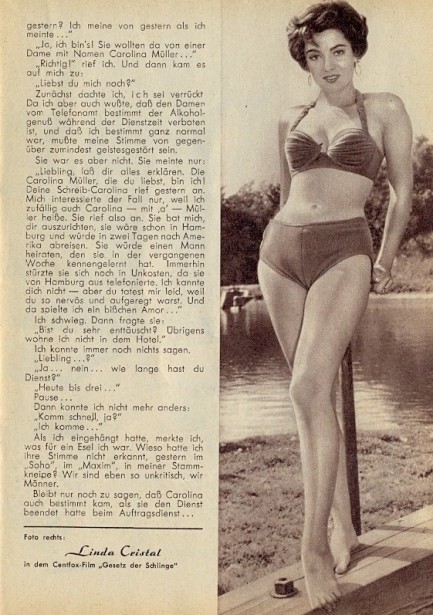

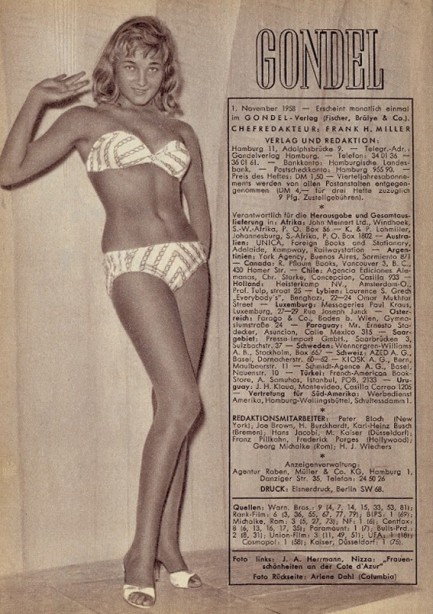

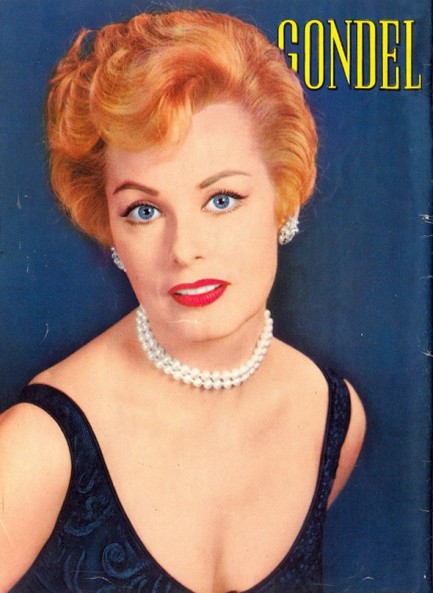

This particular Gondel is filled with unidentified passengers.

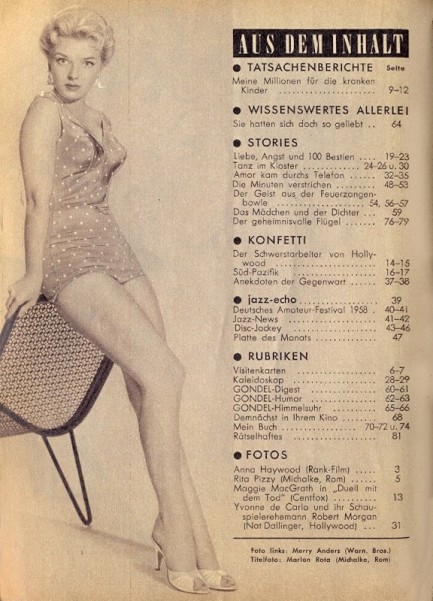

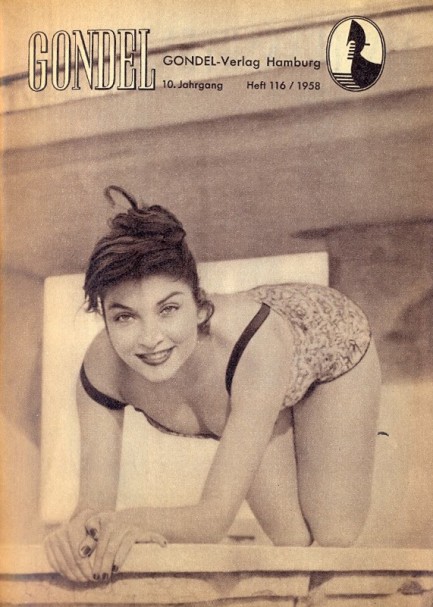

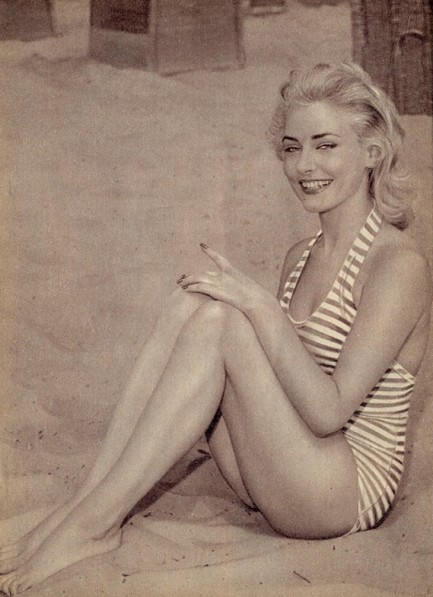

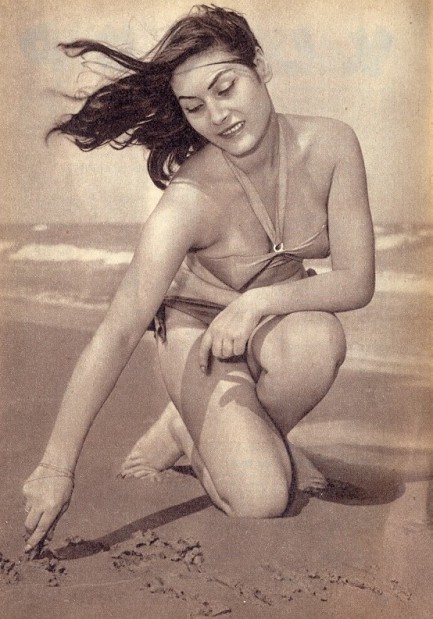

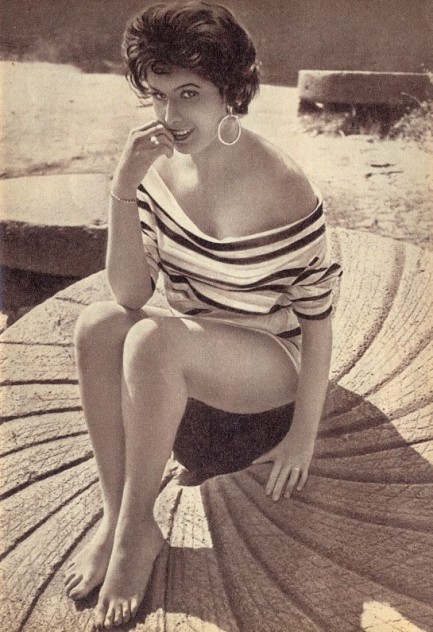

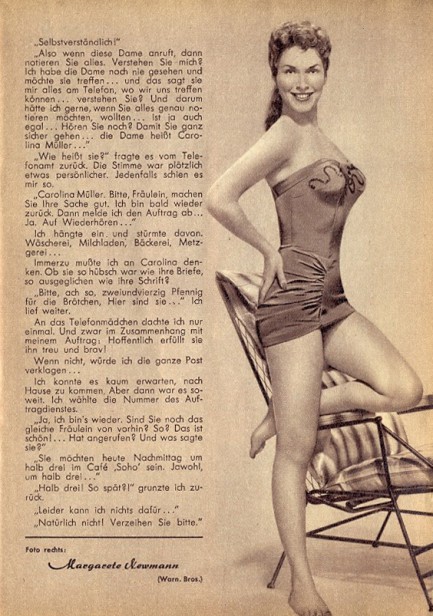

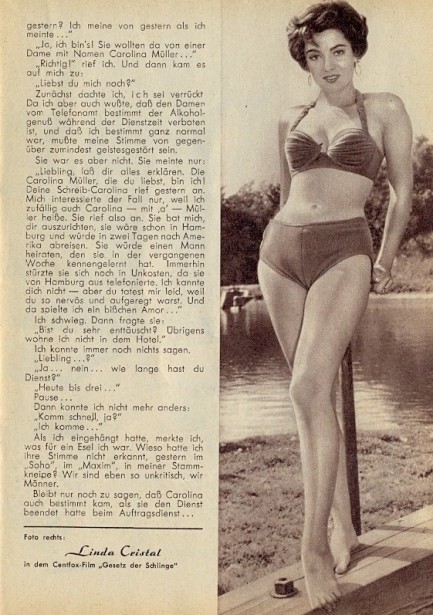

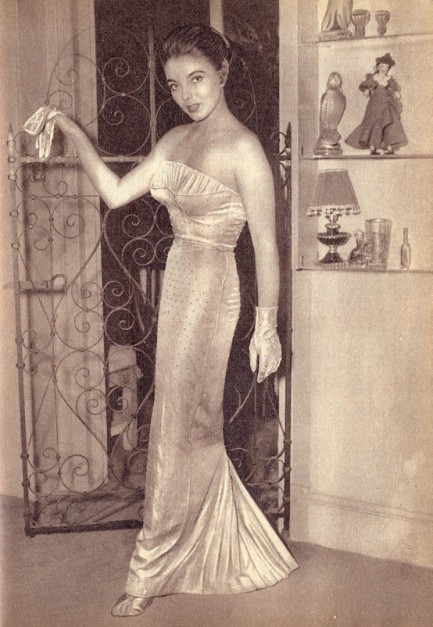

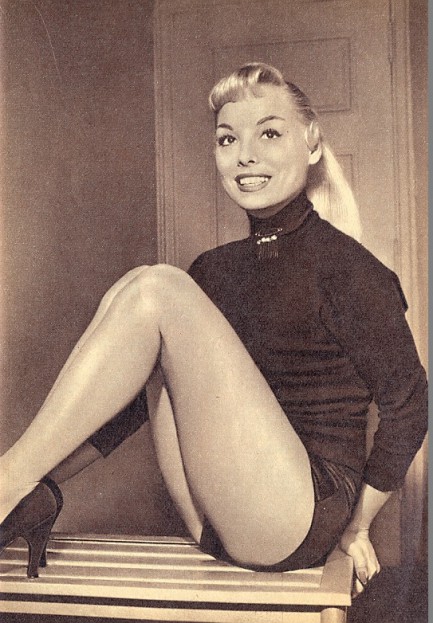

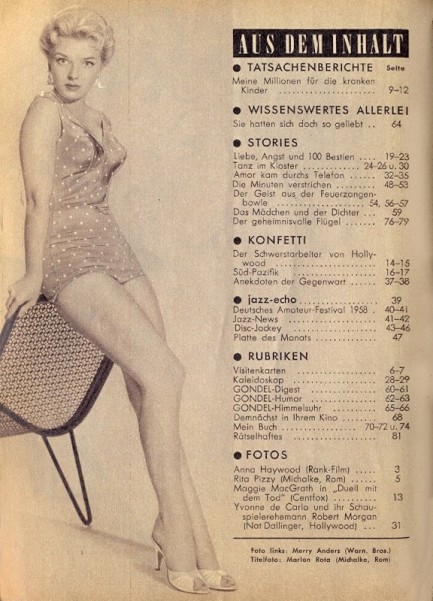

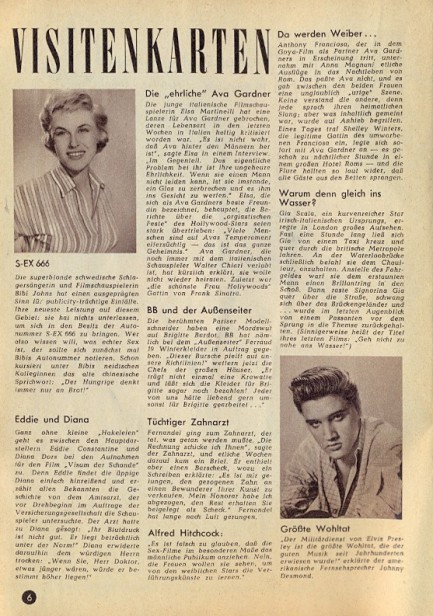

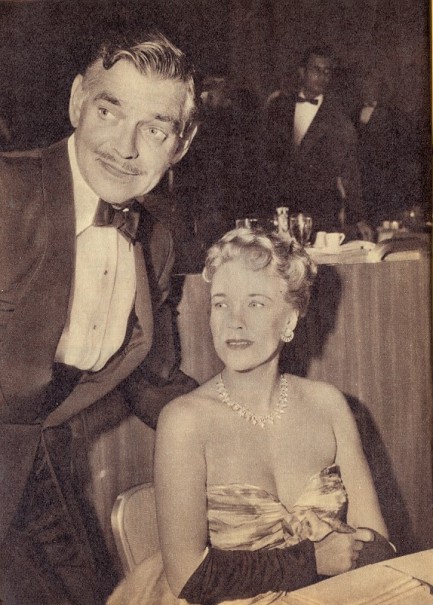

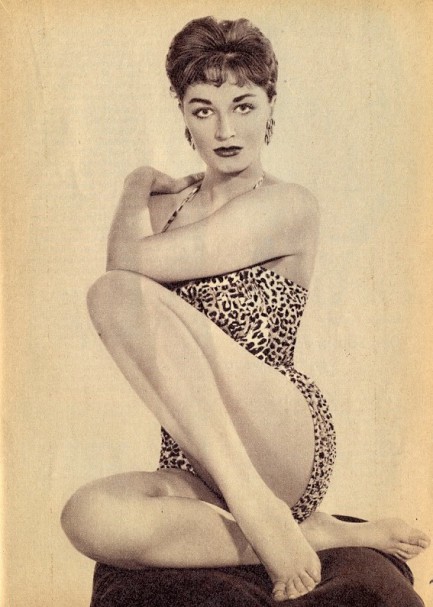

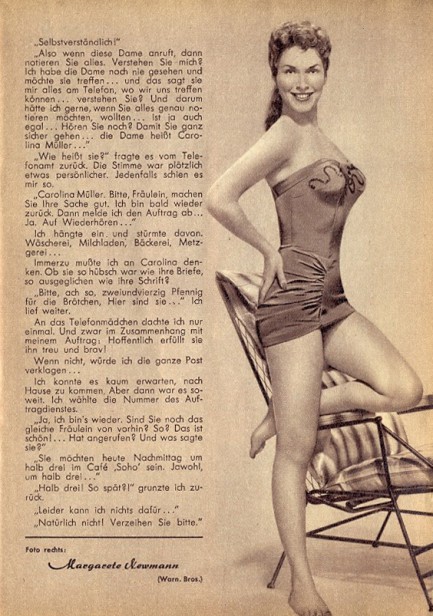

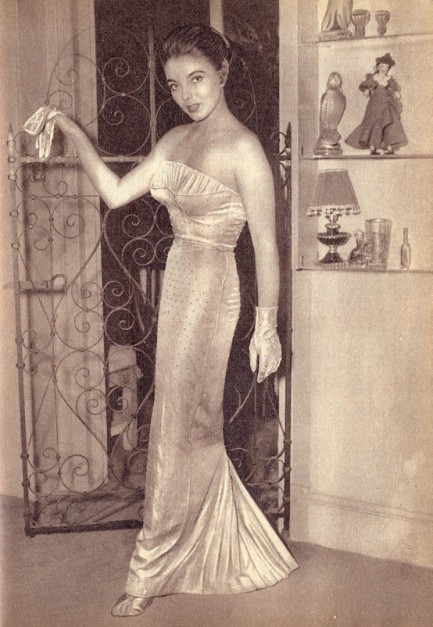

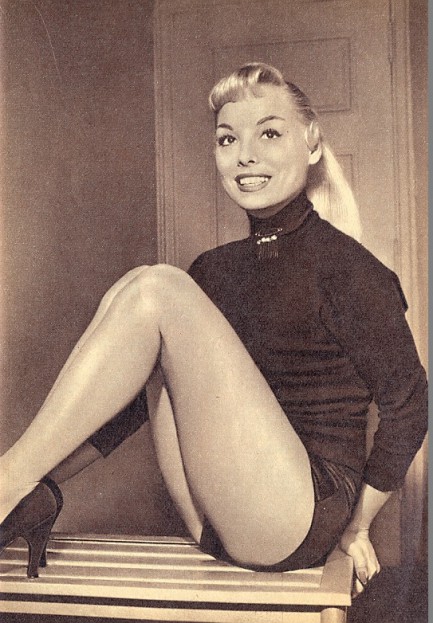

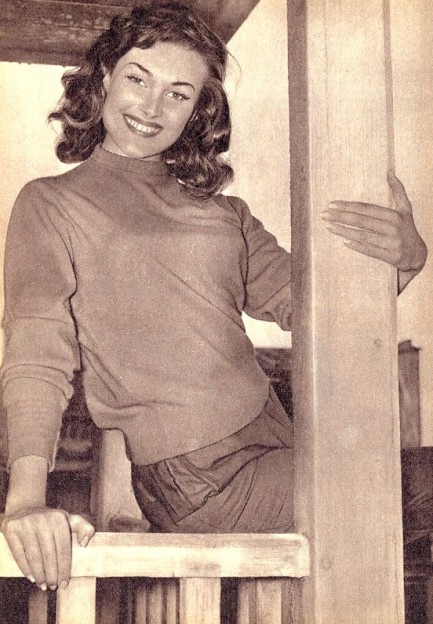

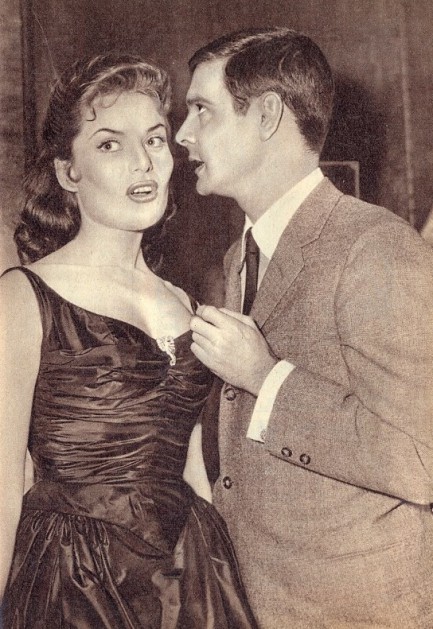

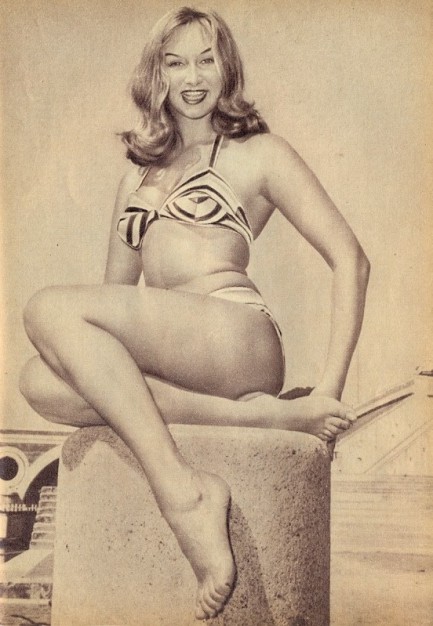

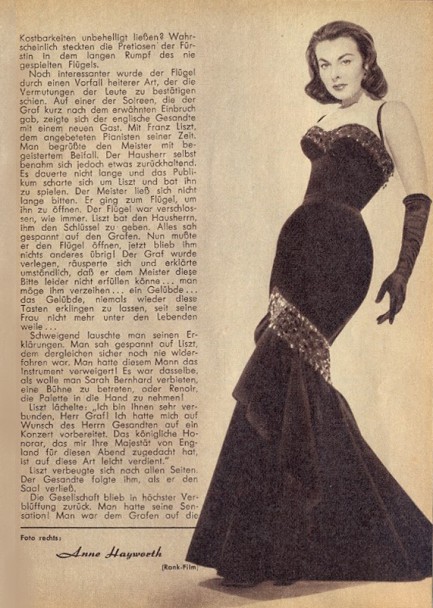

Back in 2010 we showed you some covers of the West German movie magazine Gondel, named of course after Venice’s famed banana-shaped boats. Which is fitting because Gondel later began to dedicate itself to a completely different type of banana shape by turning into a porn magazine. You see, because a banana and an erect penis are both… er… filled with potassium… *someone turns on a blender behind the bar* Anyway, it was in the 1970s when Gondel shifted gears, and theirs wasn’t an uncommon evolution among magazines around that time, as we’ve talked about before regarding the men’s adventure publication Male. Above you see the front of an issue that hit newsstands this month in 1958, and below are the interiors. The cover model is credited as Marlon Rota, as you can see by looking at masthead page where it says “titelfoto,” but no person so named ever appeared in movies. It’s possible her name is spelled wrong, because others are, but we checked similar names such as Marilyn Rota and Marlene Rota and came up blank. It’s also possible she’s just too obscure to register on the internet. So that’s another of History’s Little Mysteries™. There are others. Inside the issue you get full-page shots of, top to bottom, Anne Heywood, Merry Anders, Rita Pizzy, Clark Gable with Jean Kay, Maggie McGrath, Elga Andersen, Nuccia Morelli, Yvonne de Carlo with Robert Morgan, unknown, Margarete Neumann, Linda Cristal, Karin Himboldt, Joan Collins, unknown, Pascale Roberts, Belinda Lee with unknown, Annie Gorassini, Anne Heyworth, Mamie Van Doren, unknown, and Arlene Dahl. Got any idea who the mystery passengers are? Let us know, and meanwhile check out the Gondel covers at this link.

|

|

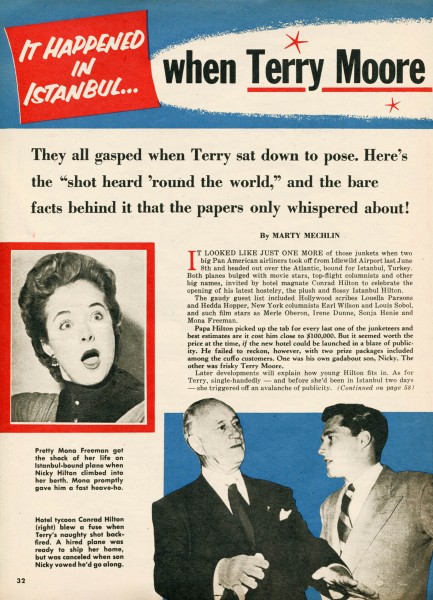

The headlines that mattered yesteryear.

2003—Hope Dies

Film legend Bob Hope dies of pneumonia two months after celebrating his 100th birthday. 1945—Churchill Given the Sack

In spite of admiring Winston Churchill as a great wartime leader, Britons elect

Clement Attlee the nation's new prime minister in a sweeping victory for the Labour Party over the Conservatives. 1952—Evita Peron Dies

Eva Duarte de Peron, aka Evita, wife of the president of the Argentine Republic, dies from cancer at age 33. Evita had brought the working classes into a position of political power never witnessed before, but was hated by the nation's powerful military class. She is lain to rest in Milan, Italy in a secret grave under a nun's name, but is eventually returned to Argentina for reburial beside her husband in 1974. 1943—Mussolini Calls It Quits

Italian dictator Benito Mussolini steps down as head of the armed forces and the government. It soon becomes clear that Il Duce did not relinquish power voluntarily, but was forced to resign after former Fascist colleagues turned against him. He is later installed by Germany as leader of the Italian Social Republic in the north of the country, but is killed by partisans in 1945.

|

|

|

It's easy. We have an uploader that makes it a snap. Use it to submit your art, text, header, and subhead. Your post can be funny, serious, or anything in between, as long as it's vintage pulp. You'll get a byline and experience the fleeting pride of free authorship. We'll edit your post for typos, but the rest is up to you. Click here to give us your best shot.

|

|